- An umbrella review published in the BMJ reported that ultra-processed food consumption is associated with an increased risk of a range of adverse health outcomes

- The most prominent were cardiometabolic disorders, mental disorders, and death from different causes.

- The findings are based on 14 published meta-analyses and studies involving almost 10 million participants.

Scientists have long been reporting that individuals consuming high amounts of certain foods or taking certain substances tend to often suffer from specific diseases or disorders (Huang et al., 2023; Samuthpongtorn et al., 2023; Tilg, 2015; Wang et al., 2023).

However, these findings often fall short of establishing a cause-and-effect link between the consumption of specific food and health outcomes. This happens because the effects of foods become visible only after prolonged periods of consumption. Experimental studies that identify cause-and-effect relationships can often not be conducted for long periods. Additionally, since many of these adverse health effects are very serious, it would not be ethical to conduct an experiment that is expected to inflict such conditions on study participants.

Experimental studies that identify cause-and-effect relationships can often not be conducted for long periods

The next best thing available to scientists is looking at the results of many studies and seeing which associations between foods and health outcomes are reported consistently in study after study, conducted in different locations, by different people, and at different times, and which were just found once or twice and never again. This is the situation where meta-analyses and umbrella reviews come into play.

What is an umbrella review?

When many studies are conducted to explore a certain topic, scientists need ways to integrate the findings of these large numbers of studies. To do this, they conduct meta-analyses, i.e., studies on studies. However, when the number of studies is so large that there are many meta-analyses covering a topic, an umbrella review is conducted to integrate their findings.

So, an umbrella review is a type of systematic review that combines evidence from a multitude of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on a certain topic. It starts with a rigorous process of searching and selecting relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses to include in the study. Assessing the quality of the included studies and integrating the findings of different reviews follows (Aromataris et al., 2015; Hedrih, 2023b).

Ultra-processed foods

Ultra-processed foods have attracted much research attention because of their links to adverse health outcomes. Ultra-processed foods are formulations made mostly or entirely from derived substances and various additives with few intact unprocessed or minimally processed food components (Hedrih, 2023a; Monteiro et al., 2019).

Ultra-processed foods have attracted much research attention because of their links to adverse health outcomes

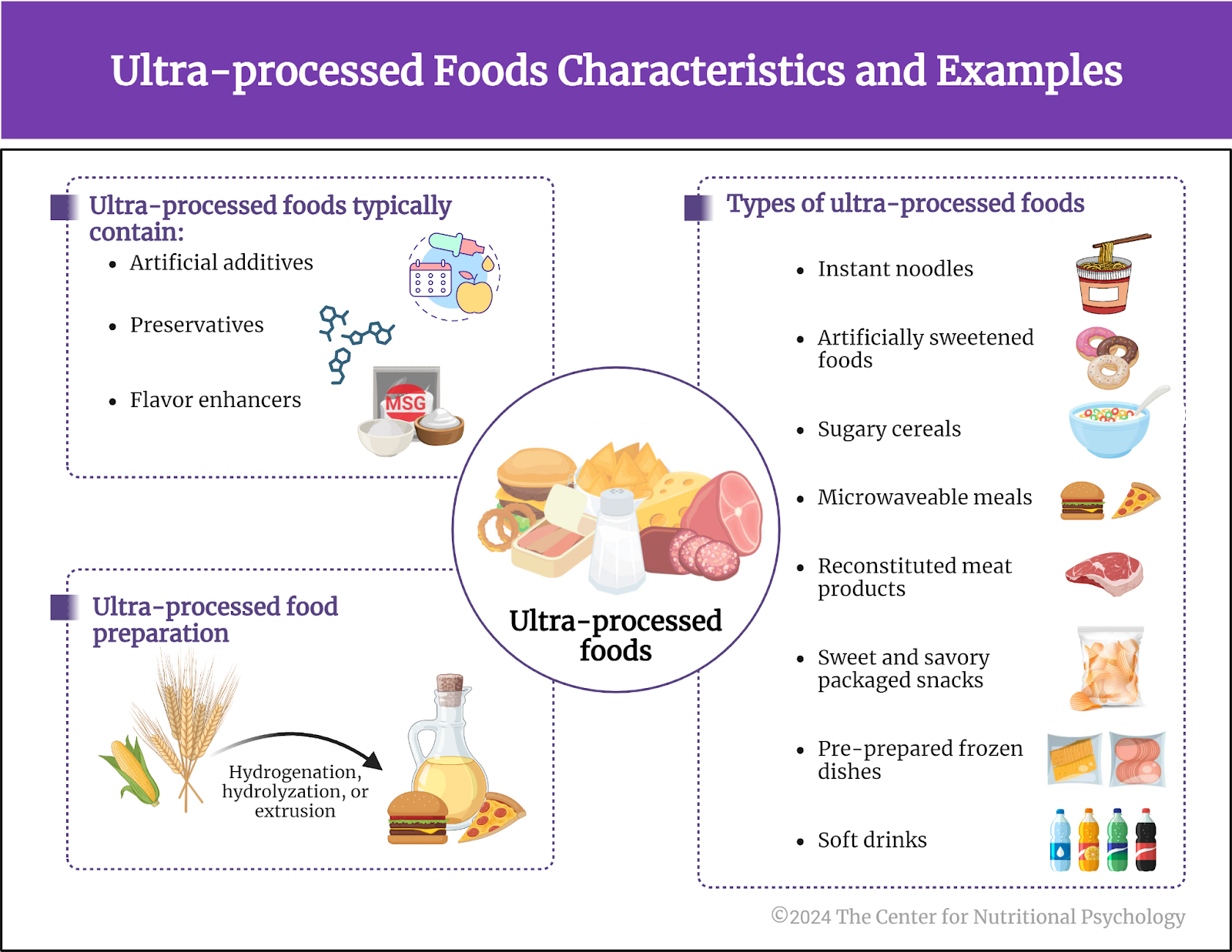

These foods typically contain artificial additives, preservatives, and flavor enhancers. Additives include dyes, color stabilizers, non-sugar sweeteners, de-foaming, anti-caking or glazing agents, emulsifiers, or humectants. Some processes used in preparing ultra-processed foods, such as hydrogenation, hydrolyzation, or extrusion, are exclusively industrial processes that cannot be performed in a regular kitchen (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ultra-processed foods characteristics and examples

Examples of ultra-processed foods include instant noodles, artificial sweeteners, artificially sweetened beverages, sugary cereals, microwaveable meals, reconstituted meat products, sweet and savory packaged snacks, pre-prepared frozen dishes, and soft drinks (Hedrih, 2023a). These foods are usually created with the intent of having a durable product that is highly palatable but also very cheap to produce, making its sale highly profitable.

The current study

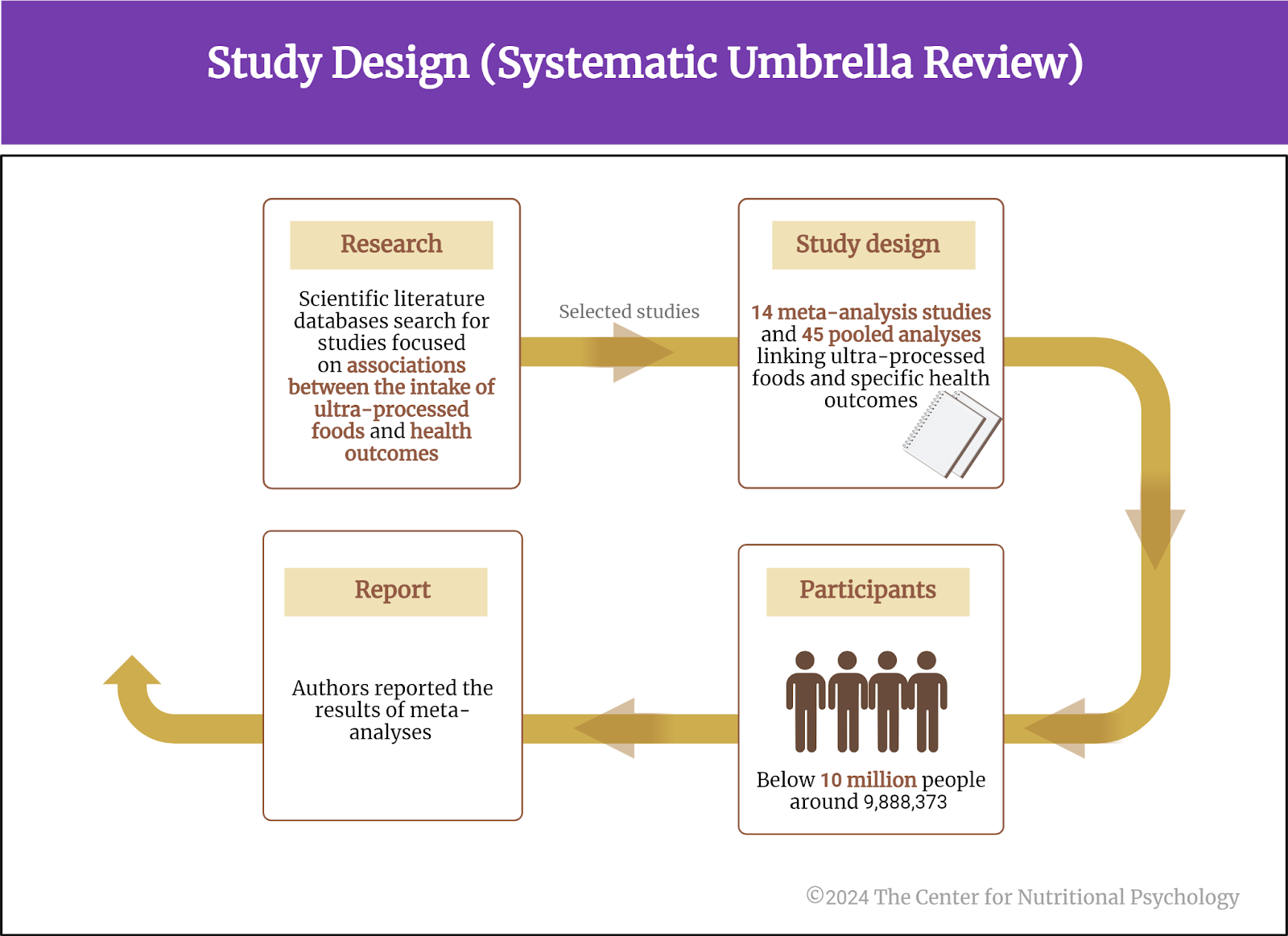

Many studies have examined the links between consuming ultra-processed foods and adverse health outcomes in the past decades. These studies were also the subject of multiple meta-analyses. Study author Melissa M Lane and her colleagues decided to conduct an umbrella review that would integrate the findings of these meta-analyses.

They searched the scientific literature databases for meta-analyses focused on associations between the intake of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes (Lane et al., 2024). This search yielded 14 published meta-analyses containing results of 45 different analyses of links between ultra-processed foods and specific health outcomes. The total number of participants in all the studies included in these meta-analyses was slightly below 10 million people (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study design (Systematic umbrella review)

The total number of participants in all the studies included in these meta-analyses was slightly below 10 million people

Individuals consuming high amounts of ultra-processed foods are more likely to develop a wide range of adverse health conditions

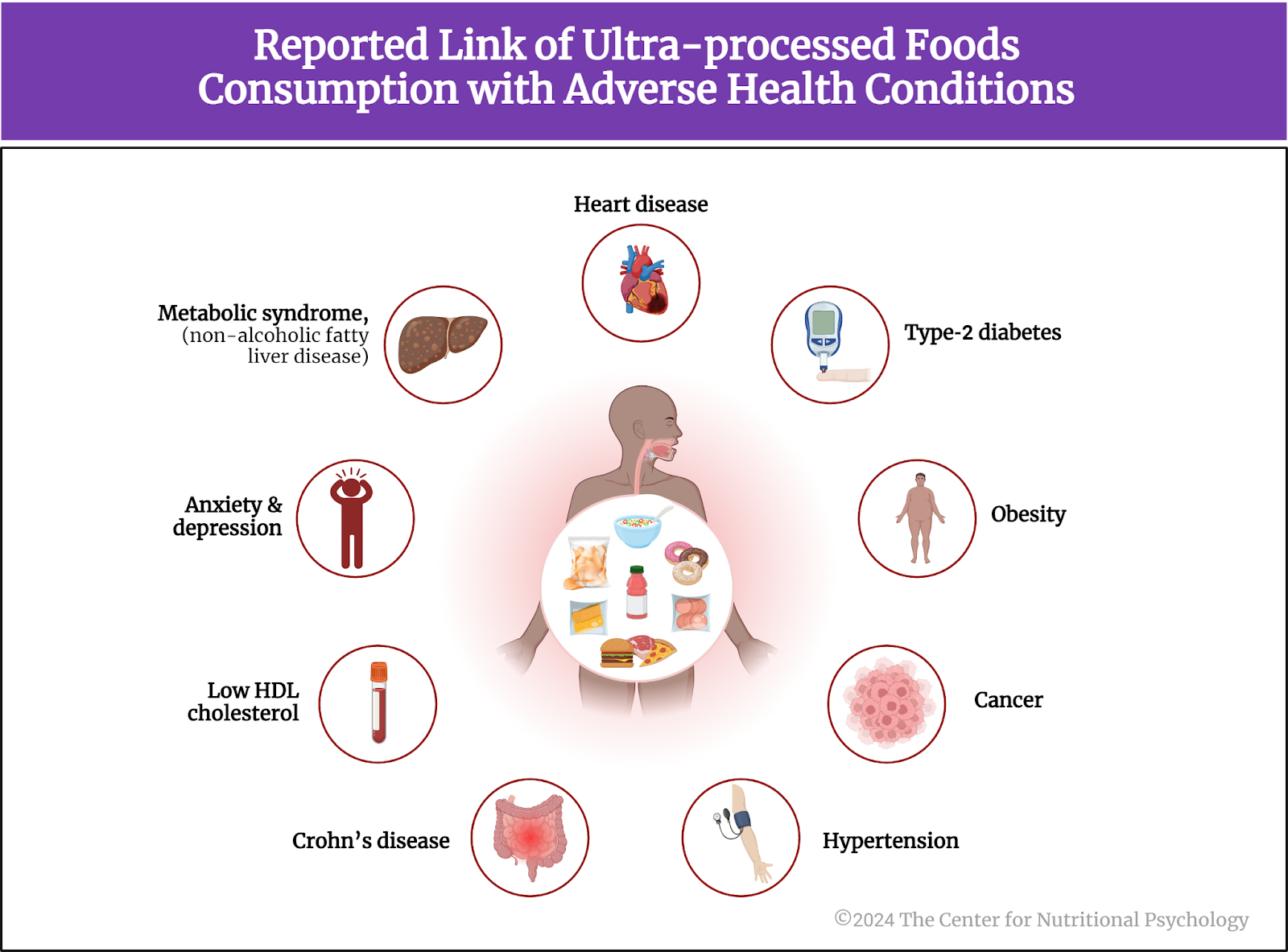

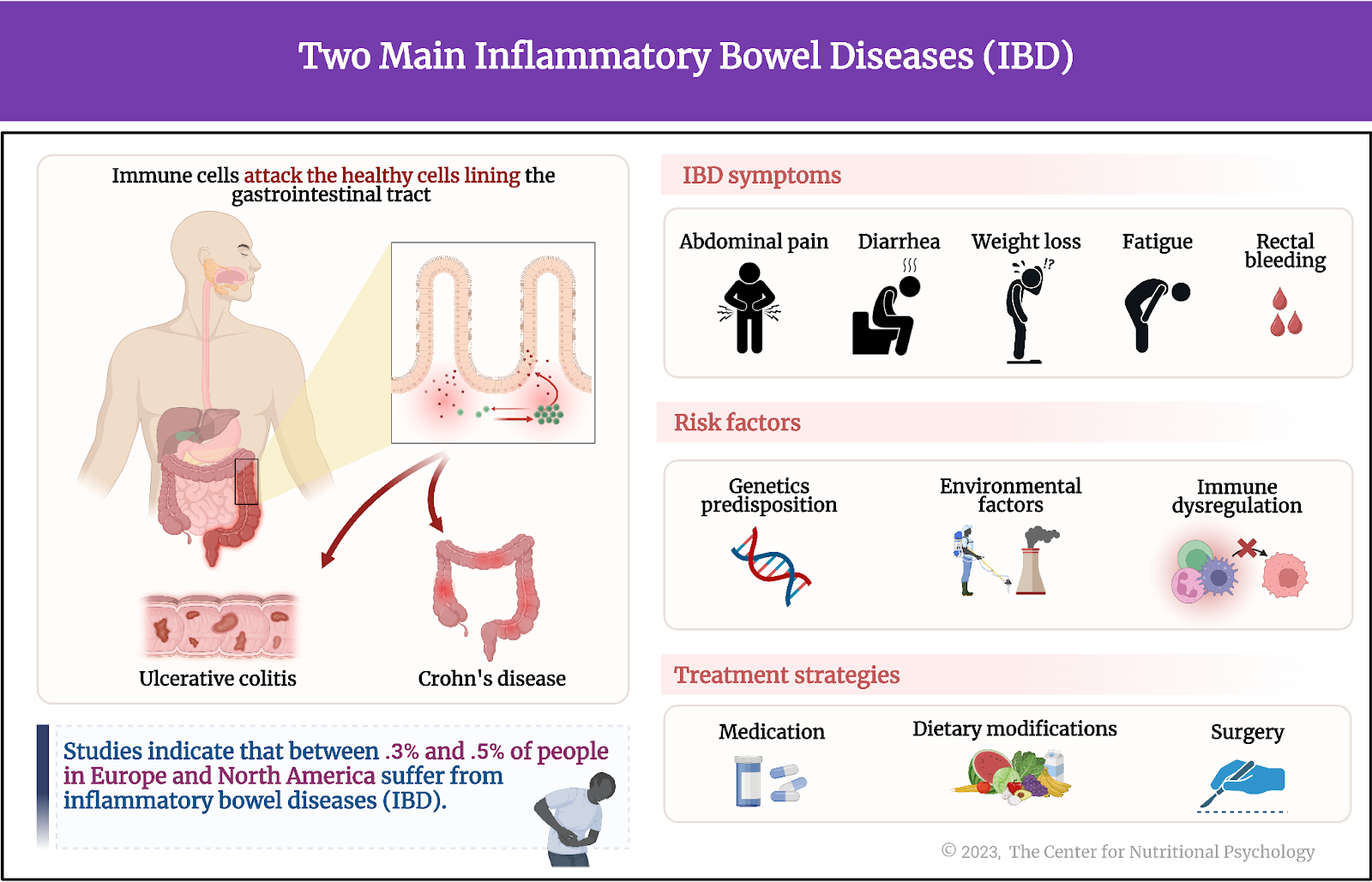

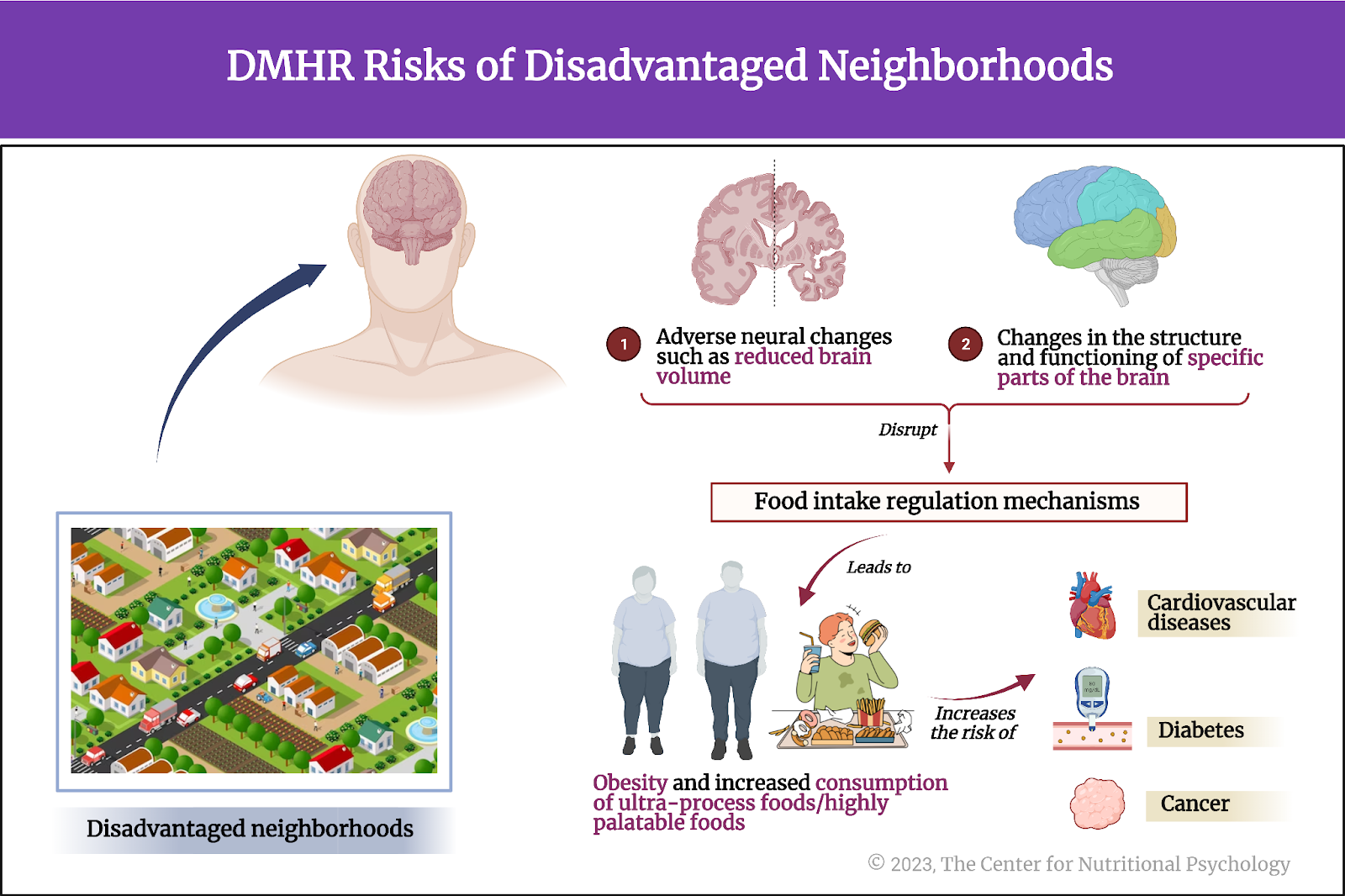

The umbrella review results confirmed the association between ultra-processed food consumption and a host of different adverse health outcomes. When the amount of ultra-processed food is considered (i.e., dose-response relations), the strongest associations were between ultra-processed food consumption and death from heart disease, Type 2 Diabetes, and obesity (particularly abdominal obesity).

When it is only considered whether an individual consumes ultra-processed foods or not, the strongest associations were with death from cardiovascular and heart disease, death from all causes, pancreatic and colorectal cancer, sleep problems, anxiety, depression, other mental disorders, wheezing, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, low HDL cholesterol, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, obesity (particularly abdominal obesity), metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and Type 2 Diabetes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Reported link of ultra-processed food consumption with adverse health conditions

Conclusion

While this type of study cannot confirm that ultra-processed food consumption is a causal factor in developing all these adverse health conditions, it clearly highlights increased health risks associated with consuming ultra-processed foods, particularly in large amounts. To make matters more serious, the risks are spread across a wide range of diseases and adverse health conditions affecting different organs and systems of organs. Many of these conditions are irreversible or fatal.

These findings, coupled with the fact that the consumption of ultra-processed foods has been increasing worldwide in recent decades, point to a need to develop public health strategies that would allow large parts of the population to replace ultra-processed foods in their diets with healthier alternatives, while still maintaining food safety and ensuring good availability of nutritious, healthy foods to these individuals.

The paper “Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses” was authored by Melissa M Lane, Elizabeth Gamage, Shutong Du, Deborah N Ashtree, Amelia J McGuinness, Sarah Gauci, Phillip Baker, Mark Lawrence, Casey M Rebholz, Bernard Srour, Mathilde Touvier, Felice N Jacka, Adrienne O’Neil, Toby Segasby, and Wolfgang Marx.

References

Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C. M., Holly, C., Khalil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

Hedrih, V. (2023a). Scientists Propose that Ultra-Processed Foods be Classified as Addictive Substances. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/scientists-propose-that-ultra-processed-foods-be-classified-as-addictive-substances/

Hedrih, V. (2023b, June 6). Health Consequences of High Sugar Consumption. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/health-consequences-of-high-sugar-consumption/

Huang, Y., Chen, Z., Chen, B., Li, J., Yuan, X., Li, J., Wang, W., Dai, T., Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wang, P., Guo, J., Dong, Q., Liu, C., Wei, Q., Cao, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 381, e071609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071609

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., Ashtree, D. N., McGuinness, A. J., Gauci, S., Baker, P., Lawrence, M., Rebholz, C. M., Srour, B., Touvier, M., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Segasby, T., & Marx, W. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Samuthpongtorn, C., Nguyen, L. H., Okereke, O. I., Wang, D. D., Song, M., Chan, A. T., & Mehta, R. S. (2023). Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Network Open, 6(9), e2334770. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34770

Tilg, H. (2015). Cruciferous vegetables: Prototypic anti-inflammatory food components. Tilg Clinical Phytoscience, 1(10). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40816-015-0011-2

Wang, A., Wan, X., Zhuang, P., Jia, W., Ao, Y., Liu, X., Tian, Y., Zhu, L., Huang, Y., Yao, J., Wang, B., Wu, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, J., Yao, W., Jiao, J., & Zhang, Y. (2023). High-fried food consumption impacts anxiety and depression due to lipid metabolism disturbance and neuroinflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(118). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2221097120

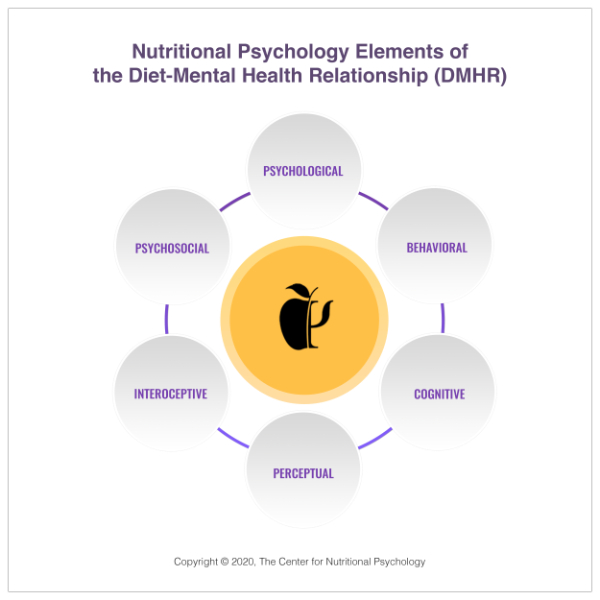

1. NP Elements Diagram

1. NP Elements Diagram