Sleeping Less Increases the Risk of Obesity and Negatively Influences the Diet-Behavior Relationship Within Nutritional Psychology

Adolescents often work strategically around their school schedules to allocate their time across studying, extracurriculars, and social activities to achieve a sense of freedom in an otherwise rigid structure. However, a compromise almost always has to be made in order to create more time, and regrettably, sleep is usually the one that becomes deprioritized (Owens et al., 2014).

A compromise is almost always made in order to create more time, and regrettably, sleep is usually the thing that becomes deprioritized.

This form of “bedtime procrastination” not only impacts the circadian rhythm that regulates the 24-hour sleep-wake cycle, but also the vital processes dependent on our body’s internal clock such as feeding behaviors. For example, lack of sleep has been associated with a higher risk of developing obesity due to dysregulated meal times, decreased self-inhibition, increased caloric intake, poorer nutritive quality of food consumed, increased sedentary time, and lowered metabolic expenditure (Duraccio et al., 2019; Krietsch et al., 2019).

“Bedtime procrastination” impacts the circadian rhythm that regulates the 24-hour sleep-wake cycle and the vital processes such as feeding behaviors.

Although studies have underscored the detrimental effects insufficient sleep has on the physical and mental health of adolescents, few have investigated the direct relationship between sleep and diet during adolescence.

To address this knowledge gap, Duraccio et al. (2021) led a crossover study on adolescent participants to understand how changes in sleep duration affected the amount, macronutrient content, and types of food they consumed. A crossover study allows observation of the same subjects across different conditions to evaluate how changes in the experiment’s design alter a specific outcome.

Duraccio et al. (2022) led a crossover study on adolescent participants to understand how changes in sleep duration affected the amount, macronutrient content, and types of food they consumed.

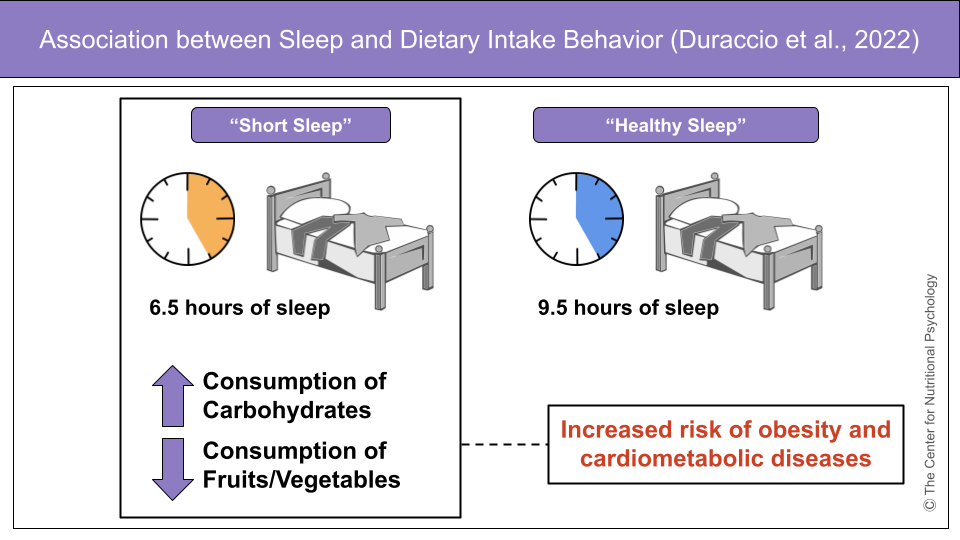

In this study, the authors wanted to investigate how different sleep durations influence both diet quality and the timing in which participants ate. To this end, the authors compared conditions of “Short Sleep” and “Healthy Sleep” (five nights for each condition, 6.5 and 9.5 hours of sleep opportunity, respectively) using wrist-worn actigraphy devices and self-reported daily sleep/wake times to track sleep length.

Figure 1. Association Between Sleep and Dietary Intake Behavior – Sleeping fewer hours per night correlated with increased consumption of carbohydrates and added sugars, and decreased intake of fruits and vegetables in adolescents, leading to an increased risk of developing obesity and related cardiometabolic diseases.

The authors report that adolescents have a greater tendency—particularly during the late evening—to consume more carbohydrates, added sugars, foods with a higher glycemic index, servings of sweet drinks, and ate fewer fruits/vegetables when they slept less (Duraccio et al., 2022). Compared to Healthy Sleep, the Short Sleep condition affected diet quality and timing of food consumption across participants. The study’s results are illuminating as they provide tangible evidence underscoring how less sleep correlates with higher risks of obesity and cardiometabolic diseases in adolescents. Moreover, the findings align and support similar work from other groups that advocate for pediatric interventions that promote better sleep to regulate healthy diet-brain signaling (Quist et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2018).

When adolescents slept less, they had a greater tendency to consume more carbohydrates, added sugars, servings of sweet drinks, and fewer fruits/vegetables.

What could be causing this association remains unclear and, accordingly, further research in this area is required. The current understanding is that this may be the body’s compensatory response to increase the consumption of high-energy foods (often unhealthy) to offset the loss of sleep, although such homeostatic drive inadvertently increases the negative risks of obesity and its comorbidities (Welsh et al., 2011, Duraccio et al., 2022). In other words, the authors discuss the correlation between the lack of sleep with less energy and the body’s natural response to eating more high-energy foods to offset this energy imbalance.

The authors discuss the correlation between the lack of sleep with less energy and the body’s natural response to eating more high-energy foods to offset the energy imbalance.

While this study’s results are subject to biases and inaccuracies as they rely on participant recall of what they ate, Duraccio et al. (2022) demonstrate how lack of sleep can alter feeding behaviors and lead to dietary changes that ultimately impact adolescent health. Be sure to see the Nutritional Psychology Research Library (NPRL) Diet and Sleep Research Category to learn more about the effect of diet on sleep.

References

Duraccio, K. M., Krietsch, K. N., Chardon, M. L., Van Dyk, T. R., & Beebe, D. W. (2019). Poor sleep and adolescent obesity risk: a narrative review of potential mechanisms. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 10, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S219594

Duraccio, K. M., Whitacre, C., Krietsch, K. N., Zhang, N., Summer, S., Price, M., Saelens, B. E., & Beebe, D. W. (2022). Losing sleep by staying up late leads adolescents to consume more carbohydrates and a higher glycemic load. Sleep, 45(3), zsab269. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab269

Krietsch, K. N., Chardon, M. L., Beebe, D. W., & Janicke, D. M. (2019). Sleep and weight-related factors in youth: A systematic review of recent studies. Sleep medicine reviews, 46, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.04.010

Miller, M. A., Kruisbrink, M., Wallace, J., Ji, C., & Cappuccio, F. P. (2018). Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep, 41(4), 10.1093/sleep/zsy018. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy018

Owens, J., Adolescent Sleep Working Group, & Committee on Adolescence (2014). Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics, 134(3), e921–e932. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1696

Quist, J. S., Sjödin, A., Chaput, J. P., & Hjorth, M. F. (2016). Sleep and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents. Sleep medicine reviews, 29, 76–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.001

Welsh, J. A., Sharma, A., Cunningham, S. A., & Vos, M. B. (2011). Consumption of added sugars and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk among US adolescents. Circulation, 123(3), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972166

Leave a comment