Lonely Women Tend To Show More Maladaptive Eating Behaviors, Study Finds

- A neuroimaging study published in JAMA Network Open found that women who feel lonely tend to show more maladaptive social behaviors.

- These women also had higher fat mass percentage, lower diet quality, and poorer mental health.

- fMRI scans showed altered brain responses to food cues in several regions.

Humans are social creatures. Because of this, relationships with other people play a central role in every individual’s life. They provide a sense of belonging, meaning, intimate connections, and emotional support we all need. Babies and children need interactions with other humans to survive. Without contact with others and its benefits, many basic cognitive capacities will not develop at all. Even in newborns, deprivation of human contact is a strong source of distress. Because of all this, social relationships are crucial to everyone’s mental and physical health and well-being (Christensson et al., 1995; Singer, 2018).

However, many individuals cannot establish or maintain a fulfilling network of interpersonal connections for different reasons. When this happens, we talk about perceived social isolation and the feeling of loneliness.

What is loneliness?

Loneliness or perceived social isolation is a subjective feeling of social isolation, disconnection, or being alone, regardless of the amount of social contact one has. The person experiencing loneliness feels empty and sad and longs for companionship. Loneliness can be a temporary state or a chronic condition. In the long run, it can have significant negative impacts on both mental and physical health, including increased risks of depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease (Park et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024).

It is important to distinguish between loneliness and solitude (i.e., being alone)

It is important to distinguish between loneliness and solitude (i.e., being alone). A person can be alone without feeling lonely. Oftentimes, solitude can be a positive and enriching experience. In contrast, the very nature of loneliness is that it is a negative experience. Still, while some people choose solitude as their preferred lifestyle, in most cases, solitude is imposed on an individual – by the death of loved ones, illness, changes to the social environment, and various other adverse processes and events (Singer, 2018).

Consequences of loneliness

Studies show that loneliness or perceived social isolation is associated with various adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Mentally, loneliness is associated with an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline, as well as a higher likelihood of experiencing stress and low self-esteem. Physically, it can lead to a weakened immune system, making one more susceptible to infections and diseases (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2003; Park et al., 2020).

Studies have also linked loneliness to an increased risk of early death and chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and atherosclerosis. Studies during the recent COVID-19 pandemic indicated that loneliness may also be associated with increased obesity, unhealthy eating habits, and cognitive decline (Zhang et al., 2024).

The current study

Study author Xiaobei Zhang and her colleagues wanted to investigate the association between loneliness (i.e., perceived social isolation) and the brain’s reactivity to food cues, eating behaviors, and mental health symptoms. They note emerging evidence indicates that the “lonely brain” may contribute to obesity, i.e., lonely individuals might show differences in brain functioning that lead to obesity.

These authors expected these changes in brain functioning would be more pronounced in individuals with worse mental health outcomes and maladaptive eating behaviors. A part of the explanation for this link might be that sugary foods help alleviate psychological pain associated with perceived social isolation. This might make individuals experiencing this type of pain more sensitive to cues for such foods.

Sugary foods help alleviate psychological pain associated with perceived social isolation

The procedure

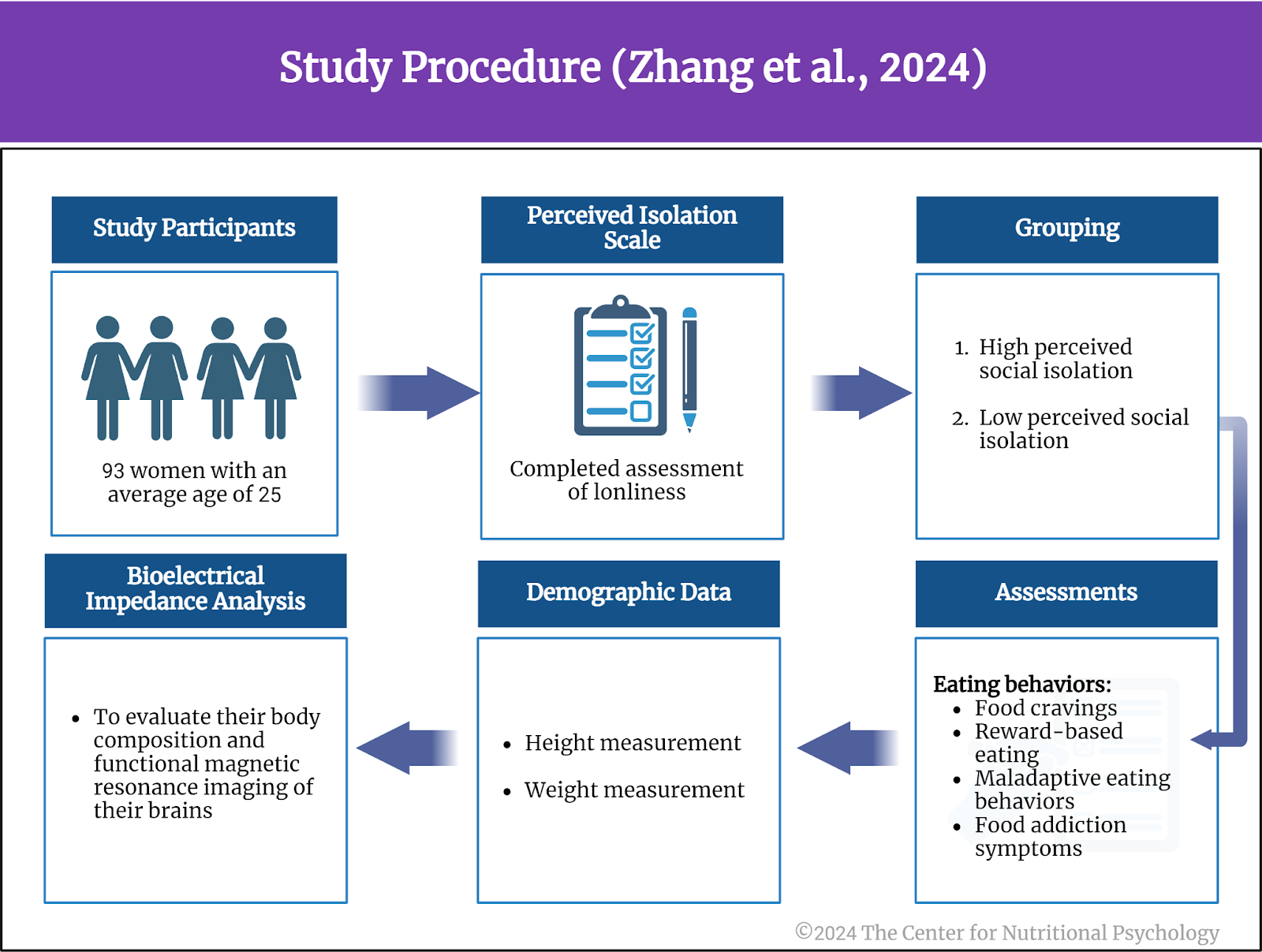

The study participants were 93 women from Los Angeles, with an average age of 25. These women completed an assessment of loneliness (the Perceived Isolation Scale). The study authors used this score to divide them into two groups: high perceived social isolation and low perceived social isolation.

The “lonely brain” may contribute to obesity

Study participants also completed assessments of their eating behaviors (food cravings, reward-based eating, maladaptive eating behaviors, and food addiction symptoms). Researchers took their height and weight measures. Participants underwent a bioelectrical impedance analysis, allowing researchers to evaluate their body composition and functional magnetic resonance imaging of their brains. During imaging, participants viewed pictures of various foods (food cue task), allowing study authors to record their brains’ reactions to pictures of food (food cues) (see Figure 1).

Figure 2. Study Procedure

The brains of lonelier women showed greater reactivity to food cues

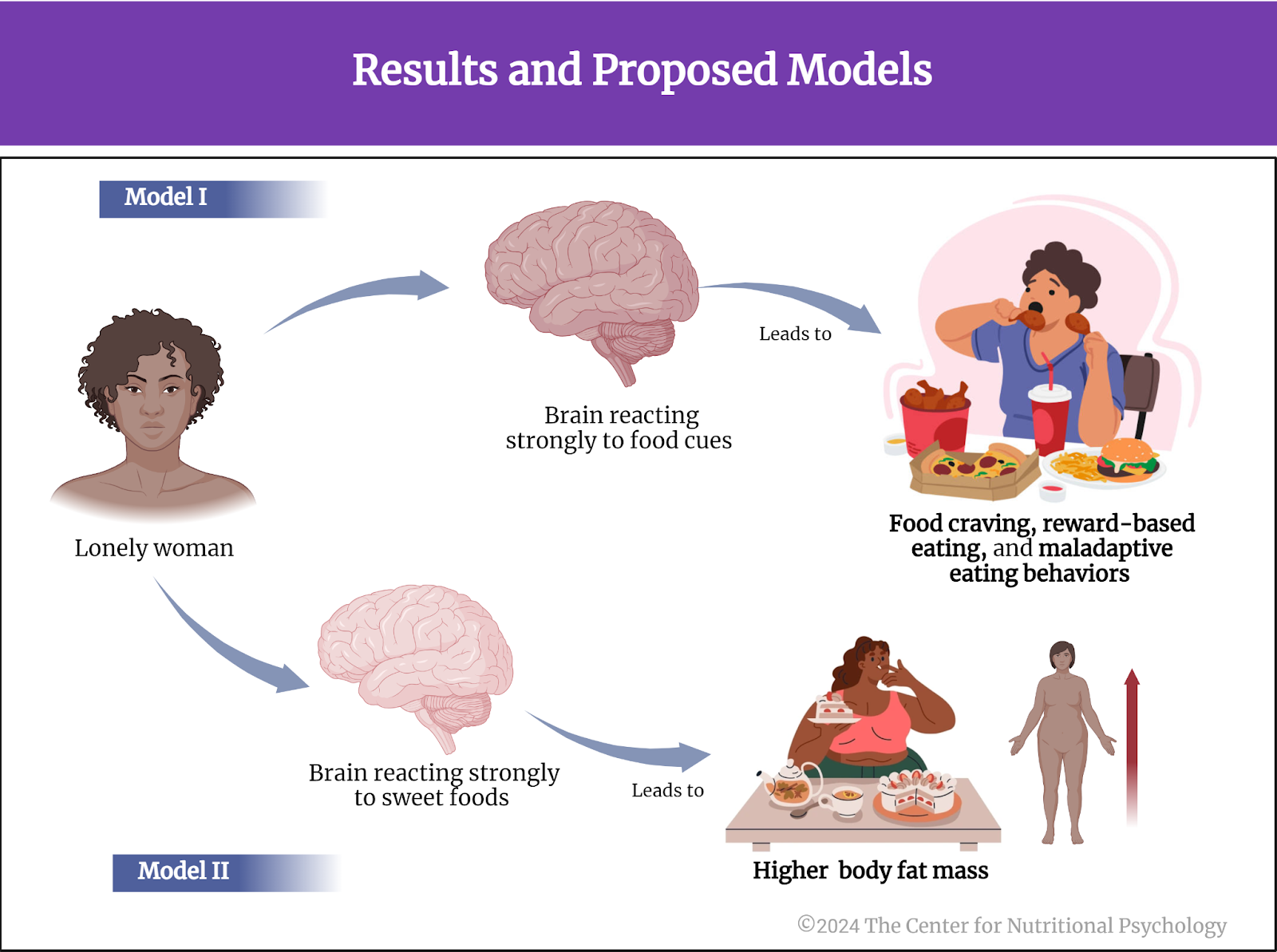

Results showed that the high social isolation group had greater reactivity to food cues (pictures of food) in the inferior parietal lobule of the brain than the low social isolation group. When viewing sweet foods, the high social isolation group had higher reactivity in the inferior parietal lobule, inferior frontal gyrus, and lateral occipital cortex. The high social isolation group had lower reactivity for savory foods in the brain’s central precuneus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex regions.

The brains of women with poorer mental health were more reactive to food cues

Participants with maladaptive eating behaviors and poorer mental health tended to show higher neural reactivity to food cues, regardless of the type of food shown. The brains of women with higher body fat percentages also tended to be more reactive to food cues.

Study authors tested a statistical model proposing that brain reactivity mediates the association between loneliness (i.e., perceived social isolation) and food cravings, reward-based eating, and overall maladaptive eating behaviors. Results showed that such a relationship between these factors is indeed possible. Reward-based eating is a behavior driven by the desire for pleasure or positive emotional response associated with consuming certain foods, often high in sugar or fat, rather than eating in response to hunger or nutritional needs.

This model proposed that it is possible that loneliness leads to increased brain reactivity to sweet foods. This increased reactivity, in turn, leads to higher body fat mass percentage (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results and proposed models

Conclusion

Overall, the study showed that the brains of women who perceive high levels of social isolation, i.e., feel very lonely and are highly reactive to food cues. This increased reactivity may lead to maladaptive eating behaviors and obesity. This indicates that alleviating and preventing social isolation may, at the same time, contribute to preventing obesity. Similarly, obesity prevention programs would benefit from considering loneliness and fulfilling social connections as important contributing factors.

The study shows that the brains of women who perceive high levels of social isolation, i.e., feel very lonely, are highly reactive to food cues

The paper “Social Isolation, Brain Food Cue Processing, Eating Behaviors, and Mental Health Symptoms” was authored by Xiaobei Zhang, Soumya Ravichandran, Gilbert C. Gee, Tien S. Dong, Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez, May C. Wang, Lisa A. Kilpatrick, Jennifer S. Labus, Allison Vaughan, and Arpana Gupta.

References

Christensson, K., Cabrera, T., Christensson, E., Uvnäs–Moberg, K., & Winberg, J. (1995). Separation distress call in the human neonate in the absence of maternal body contact. Acta Paediatrica, 84(5), 468–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13676.x

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 17(1, Supplement), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9

Park, C., Majeed, A., Gill, H., Tamura, J., Ho, R. C., Mansur, R. B., Nasri, F., Lee, Y., Rosenblat, J. D., Wong, E., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). The Effect of Loneliness on Distinct Health Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514

Singer, C. (2018). Health Effects of Social Isolation and Loneliness. Journal of Aging and Care, 28(1), 4–8.

Zhang, X., Ravichandran, S., Gee, G. C., Dong, T. S., Beltrán-Sánchez, H., Wang, M. C., Kilpatrick, L. A., Labus, J. S., Vaughan, A., & Gupta, A. (2024). Social Isolation, Brain Food Cue Processing, Eating Behaviors, and Mental Health Symptoms. JAMA Network Open, 7(4), e244855. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.4855

Leave a comment