How did the COVID-19 Pandemic Influence the Diet Mental Health Relationship in 5,000 Households?

The COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating across many aspects of life. From health concerns to financial insecurities, many have endured the challenging circumstances imposed by social distancing and public health measures aimed to contain contagious outbreaks.

Throughout the pandemic, changes in lifestyle and the loss of community from isolation have resulted in increased reports of mental health issues (Wilder-Smith & Freedman, 2020). The prevalence of anxiety and depression has motivated health professionals to consider new and different strategies to prevent and treat mental illnesses. A healthy diet is often recommended as a viable option to improve mental health.

The prevalence of anxiety and depression has motivated health professionals to consider different strategies to prevent and treat mental illnesses.

Since the pandemic has not only harmed food security but also the ability of individuals to maintain balanced diets, Coletro and colleagues were interested in identifying both how eating behaviors have changed during the pandemic, and whether these changes correlate with the higher incidence of anxiety and depression (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Huizar et al., 2021).

Focusing on the Brazilian urban population and through an epidemiological approach, Coletro et al. (2022) utilized household surveys to assess mental illness symptoms and food consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. They employed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item test to evaluate anxiety (Löwe et al., 2008) and the Patient Health Questionnaire for depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). To assess the quality of participants’ diet, a NOVA classification food questionnaire—a system developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations—was incorporated to quantify how frequently participants consumed fresh/minimally processed and ultra-processed foods (Monteiro et al., 2010; Meireles et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021).

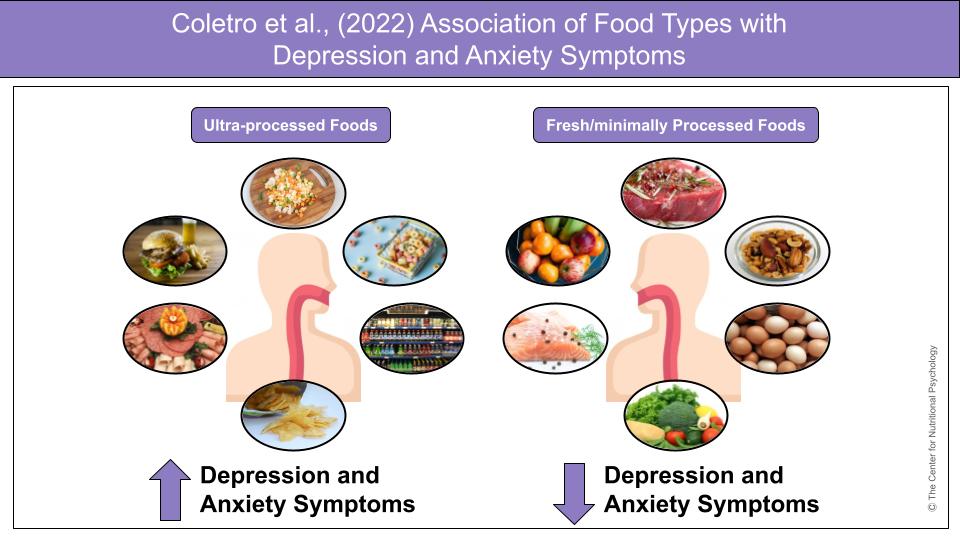

In this study, fresh and minimally processed foods included beans, nuts, vegetables, red meat, chicken, fish, eggs, and fruits, whereas ultra-processed foods include soft drinks, packaged snacks, instant foods, processed meats like hamburgers, frozen products, bread, and sweets.

Figure 1. Eating more fresh/minimally processed foods is associated with a lower prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms, while consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with higher reports of depression and anxiety.

With data collected from over 5,000 households, the authors found that eating fresh/minimally processed foods above the weekly average frequency was associated with a lower prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms. In contrast, eating ultra-processed foods above the weekly average was associated with a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression (Figure 1).

Eating fresh/minimally processed foods above the weekly average frequency was associated with a lower prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms.

However, as this was a cross-sectional study where data were collected from participant self-responses at a specific time, it does not warrant causality between the consumption of processed foods and mental health symptoms. Nevertheless, the study’s results demonstrate that not only does nutrition relate to mental health but they also shed light on the importance of creating a balanced diet full of fresh and minimally processed foods. Nutrient deficiency increases the risk of inflammatory reactions in the brain and has been associated with the onset of mental illnesses (Grosso et al., 2014). Moreover, ultra-processed foods are poor in necessary micronutrients like vitamins and polyphenols, which are metabolized into essential, anti-inflammatory fatty acids that modulate critical mood neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine.

References

Coletro, H. N., Mendonça, R. D., Meireles, A. L., Machado-Coelho, G., & Menezes, M. C. (2022). Ultra-processed and fresh food consumption and symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID – 19 pandemic: COVID Inconfidentes. Clinical nutrition ESPEN, 47, 206–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.12.013

Di Renzo, L., Gualtieri, P., Pivari, F., Soldati, L., Attinà, A., Cinelli, G., Leggeri, C., Caparello, G., Barrea, L., Scerbo, F., Esposito, E., & De Lorenzo, A. (2020). Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. Journal of translational medicine, 18(1), 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5

Grosso, G., Galvano, F., Marventano, S., Malaguarnera, M., Bucolo, C., Drago, F., & Caraci, F. (2014). Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: Scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2014, 313570. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/313570

Huizar, M. I., Arena, R., & Laddu, D. R. (2021). The global food syndemic: The impact of food insecurity, Malnutrition and obesity on the healthspan amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 64, 105–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.07.002

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical care, 46(3), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Meireles, A. L., Lourenção, L. G., de Menezes Junior, L. A. A., Coletro, H. N., Justiniano, I. C. S., de Moura, S. S., … & Machado-Coelho, G. L. L. (2021). COVID-Inconfidentes-SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in two Brazilian urban areas during the pandemic first wave: study protocol and initial results.

Monteiro, C. A., Levy, R. B., Claro, R. M., Castro, I. R., & Cannon, G. (2010). A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cadernos de saude publica, 26(11), 2039–2049. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311×2010001100005

Wang, L., Martínez Steele, E., Du, M., Pomeranz, J. L., O’Connor, L. E., Herrick, K. A., Luo, H., Zhang, X., Mozaffarian, D., & Zhang, F. F. (2021). Trends in Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods Among US Youths Aged 2-19 Years, 1999-2018. JAMA, 326(6), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.10238

Wilder-Smith, A., & Freedman, D. O. (2020). Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Journal of travel medicine, 27(2), taaa020. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa020

Leave a comment