Can Experiencing Chronic Discrimination Make Our Brains More Reactive to Food Cues?

Listen to this Article

- A neuroimaging study published in Nature Mental Health found that individuals experiencing high levels of unfair treatment have stronger reactions to food cues in areas of the brain involved in reward processing and self-control.

- Their willingness to eat unhealthy foods was also increased, particularly for unhealthy sweet foods.

- These individuals tended to have increased levels of two gut metabolites.

When we suddenly find ourselves in a dangerous situation, our body activates a series of changes that prepare us to fight the source of the danger or flee from it. It will release stress hormones into our bloodstream; the heart will start beating faster, breathing will quicken, and sweating will increase. We will forget about being hungry, sleepy, or tired. This is called the acute stress response. However, the acute stress response is only temporary. As soon as the danger is over, the source of stress no longer threatens us; all the processes will return to normal. But what happens if the danger does not end if the cause of stress continues to threaten our well-being?

Chronic stress

When the state of stress persists and continues for an extended period, we call it chronic stress. In modern society, chronic stress typically arises from enduring circumstances such as work-related pressures, financial difficulties, or strained relationships. It can also be a consequence of more catastrophic events such as life in a warzone, slavery, societal collapse, persecution, or other sources of serious stress (Bezo & Maggi, 2015; de Tubert, 2006; Hedrih et al., 2018; Hedrih & Husremović, 2021).

Chronic stress exposes the body to increased levels of stress hormones, such as cortisol and catecholamines, for prolonged periods. Studies indicate that this can, in turn, lead to detrimental effects on physical and mental health, including an increased risk of heart disease, anxiety disorders, depression, or changes in immune system activity (Adell et al., 1988; Hedrih, 2023; Tafet & Bernardini, 2003; Torpy et al., 2007).

Individuals under chronic stress tend to increase their food intake and shift their preferences toward sweet and fatty foods

Chronic stress also changes appetite. Individuals under chronic stress tend to increase their food intake and shift their preferences towards sweet and fatty foods. Researchers have come to call such foods “comfort foods” (Dallman et al., 2005).

Chronic stress and discrimination

Discrimination is the unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people, especially on the grounds of race, age, sex, or disability. When a society accepts discriminatory practices, they become an important source of chronic psychosocial stress for exposed individuals. Such experiences can lead to all the adverse consequences related to chronic stress, including changes in appetite. In this way, exposure to discrimination can contribute to stress-related weight gain and obesity (Zhang et al., 2023).

Exposure to discrimination can contribute to stress-related weight gain and obesity

The current study

Study author Xiaobei Zhang wanted to explore the link between exposure to discrimination and neural reactivity to healthy and unhealthy food cues and certain gut metabolites. Their expectation was that individuals more exposed to discrimination would have different brain activity in areas of the brain processing rewards and self-control when seeing unhealthy foods compared to individuals with lower levels of discrimination experiences. Their second expectation was that levels of specific biochemicals involved in inflammation (glutamate metabolites) would differ in individuals exposed to more discrimination (Zhang et al., 2023).

The procedure

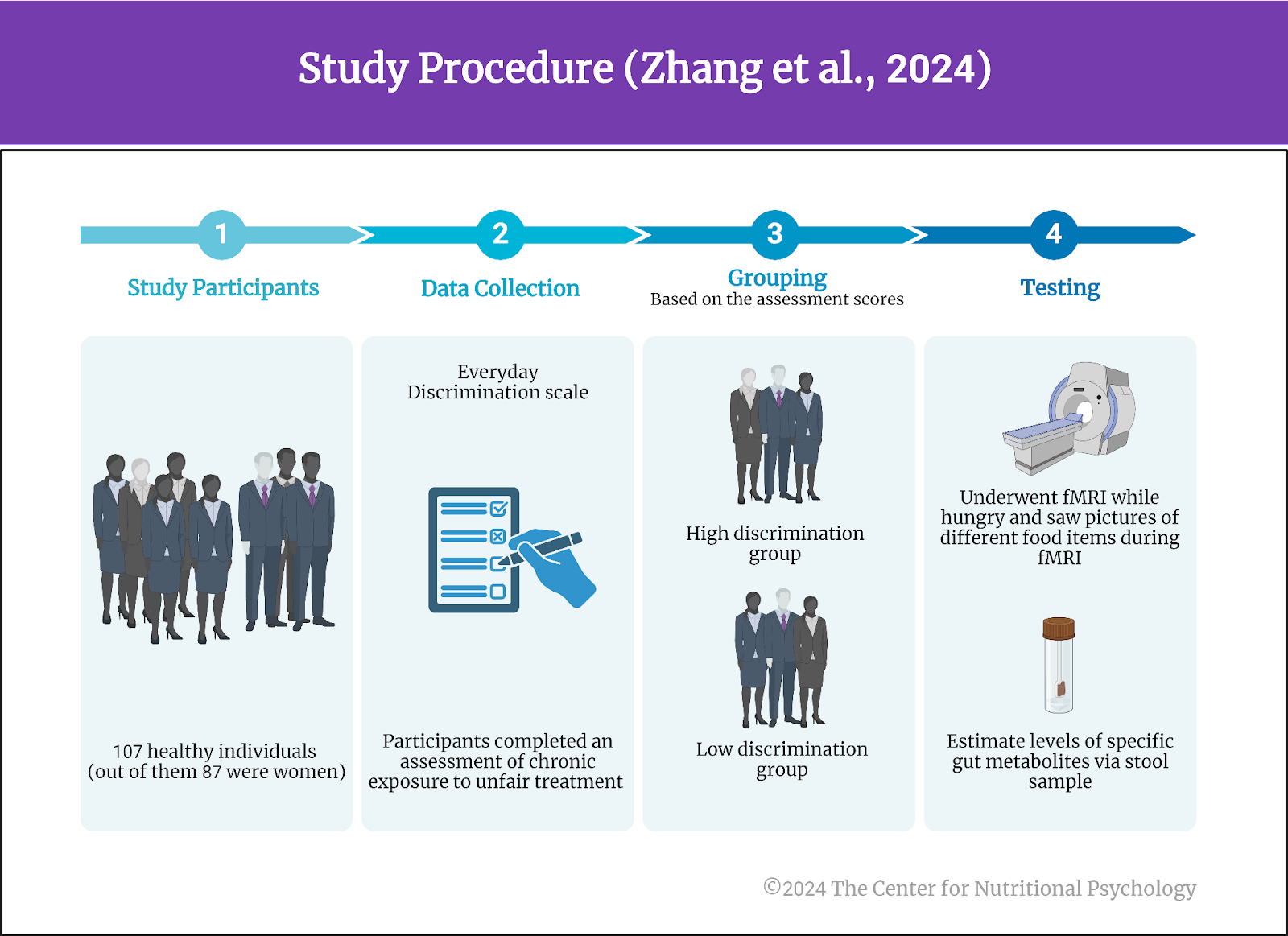

The study participants were 107 healthy individuals recruited from Los Angeles through advertisements and local clinics. 87 of them were women (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Procedure (Zhang et al., 2024)

Figure 1. Study Procedure (Zhang et al., 2024)

These individuals completed an assessment of chronic exposure to unfair treatment (the Everyday Discrimination scale). This assessment does not target discrimination specifically but captures different chronic experiences of unfair treatment in various domains of everyday life, including discrimination. Based on the scores of this assessment, the study authors divided the participants into two groups: those experiencing high levels of unfair treatment (the high discrimination group) and those experiencing comparatively low levels of such treatments (the low discrimination group).

Participants also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging while hungry, i.e., after not having eaten for 6 hours. During the imaging, researchers showed participants pictures of different food items and recorded their brains’ reactions to the pictures. At the end of the scan, participants reported their willingness to eat the foods shown. Additionally, participants gave stool samples that allowed the study authors to estimate levels of specific gut metabolites.

The brains of individuals exposed to high levels of unfair treatment tend to be more reactive to unhealthy, sweet foods

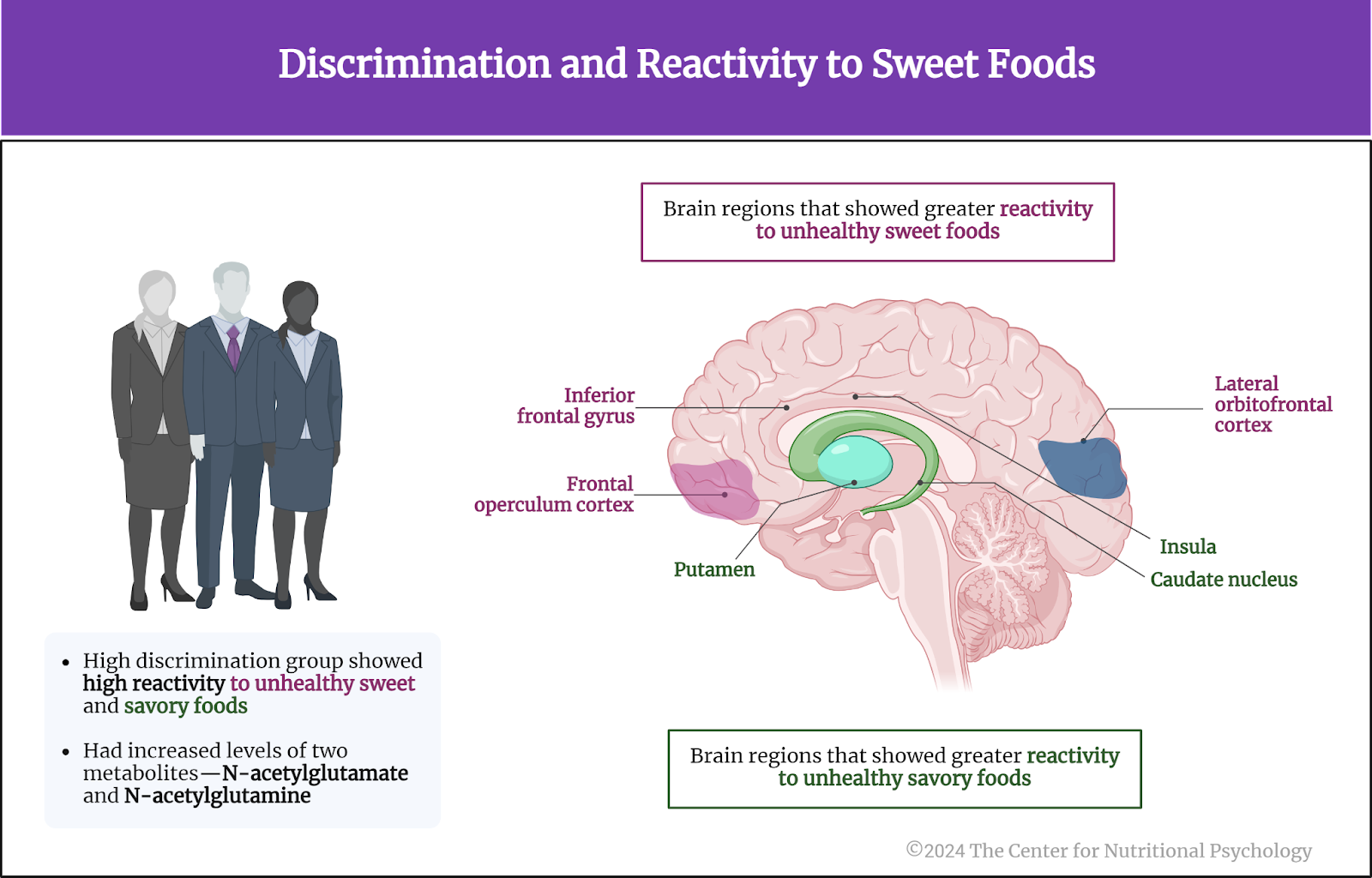

Results showed that the brains of individuals from the high discrimination group were more reactive to unhealthy sweet foods. Regions that showed greater reactivity were the insula, inferior frontal gyrus, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and frontal operculum cortex. The brains of these individuals also had stronger reactions to unhealthy savory foods in the caudate, putamen, insula, frontal pole, and lateral orbitofrontal cortex. These areas of the brain process emotions, decision-making, reward, and self-control (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Discrimination and reactivity to sweet foods

Figure 2. Discrimination and reactivity to sweet foods

When unhealthy sweet foods were compared with healthy sweet foods, the high discrimination group had lower food-cue reactivity towards unhealthy sweet foods than the low discrimination group in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

The high discrimination group also had increased levels of two metabolites—N-acetylglutamate and N-acetylglutamine. Additionally, these individuals tended to express greater willingness to eat unhealthy foods than the low discrimination group, which was not the case with healthy foods.

Conclusion

The study showed that the brains of individuals experiencing greater levels of unfair treatment in their everyday lives tend to be more reactive to unhealthy, sweet foods. They were also more willing to eat such foods.

Experiencing unfair treatment can contribute to increased neural reactivity to unhealthy food cues

The study shows that experiencing unfair treatment can contribute to increased neural reactivity to unhealthy food cues. This can, in turn, promote unhealthy eating behaviors, increasing the risk of obesity.

The paper “Discrimination exposure impacts unhealthy processing of food cues: crosstalk between the brain and gut” was authored by Xiaobei Zhang, Hao Wang, Lisa A. Kilpatrick, Tien S. Dong, Gilbert C. Gee, Jennifer S. Labus, Vadim Osadchiy, Hiram Beltran-Sanchez, May C. Wang, Allison Vaughan, and Arpana Gupta.

References

Adell, A., Garcia-Marquez, C., Armario, A., & Gelpi, E. (1988). Chronic Stress Increases Serotonin and Noradrenaline in Rat Brain and Sensitizes Their Responses to Further Acute Stress. Journal of Neurochemistry, 50(6), 1678–1681. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb02462.x

Bezo, B., & Maggi, S. (2015). Living in “survival mode:” Intergenerational transmission of trauma from the Holodomor genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. Social Science and Medicine, 134, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.009

Dallman, M. F., Pecoraro, N. C., & La Fleur, S. E. (2005). Chronic stress and comfort foods: Self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 19(4), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBI.2004.11.004

de Tubert, R. H. (2006). Social trauma: The pathogenic effects of untoward social conditions. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 15(3), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/08037060500526037

Hedrih, V. (2023). Immune Mechanism Linking Changes in Gut Microorganism and Behavior after Chronic Stress. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/researchers-discover-immune-mechanism-linking-changes-in-gut-microorganisms-and-behavior-after-chronic-stress/

Hedrih, V., & Husremović, D. (2021). Organizational Psychology: Traumatic Traces in Organizations. In A. Hamburger, C. Hancheva, & V. D. Volkan (Eds.), Social Trauma—An Interdisciplinary Textbook (pp. 235–243). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47817-9

Hedrih, V., Pedović, I., & Pejičić, M. (2018). Attachment in postwar societies of Ex Yugoslavia. In A. Hamburger (Ed.), Trauma, Trust, and Memory: Social Trauma and Reconciliation in Psychoanalysis (pp. 141–151). Routledge.

Tafet, G. E., & Bernardini, R. (2003). Psychoneuroendocrinological links between chronic stress and depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 27(6), 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00162-3

Torpy, J. M., Lynm, C., & Glass, R. M. (2007). Chronic Stress and the Heart. JAMA, 298(14), 1722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.14.1722

Zhang, X., Wang, H., Kilpatrick, L. A., Dong, T. S., Gee, G. C., Labus, J. S., Osadchiy, V., Beltran-Sanchez, H., Wang, M. C., Vaughan, A., & Gupta, A. (2023). Discrimination exposure impacts unhealthy processing of food cues: Crosstalk between the brain and gut. Nature Mental Health, 1(11), 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00134-9

Leave a comment