Microbiota composition is linked to both positive and negative aspects of mental health

A large-scale study in Belgium and the Netherlands found links between the abundance of certain groups of gut bacteria species and mental health outcomes. Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus bacteria that produce a short-chain fatty acid called butyrate were consistently more abundant in individuals with higher quality of life. In contrast, Dialister, Coprococcus spp, tended to be depleted in individuals with depression. Social functioning tended to be better in individuals with many bacteria capable of producing 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid in their gut. 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid is a substance our body produces when processing dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with experiencing good feelings (Valles-Colomer et al., 2019). The study was published in Nature Microbiology.

Social functioning was better in those with bacteria capable of producing a substance our body produces (3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid) when processing dopamine

Humans have known for centuries that there is a link between how our digestive system works and how we feel. Everyone senses from experience that our mental state also deteriorates when our digestive system doesn’t work well. However, in the past century, medical and biological science has advanced enough to allow scientists to examine the gut microbiota in our digestive system and study the interaction between them and the human body in detail.

A large-scale study found links between the abundance of certain gut bacteria species and mental health outcomes

What is gut microbiota?

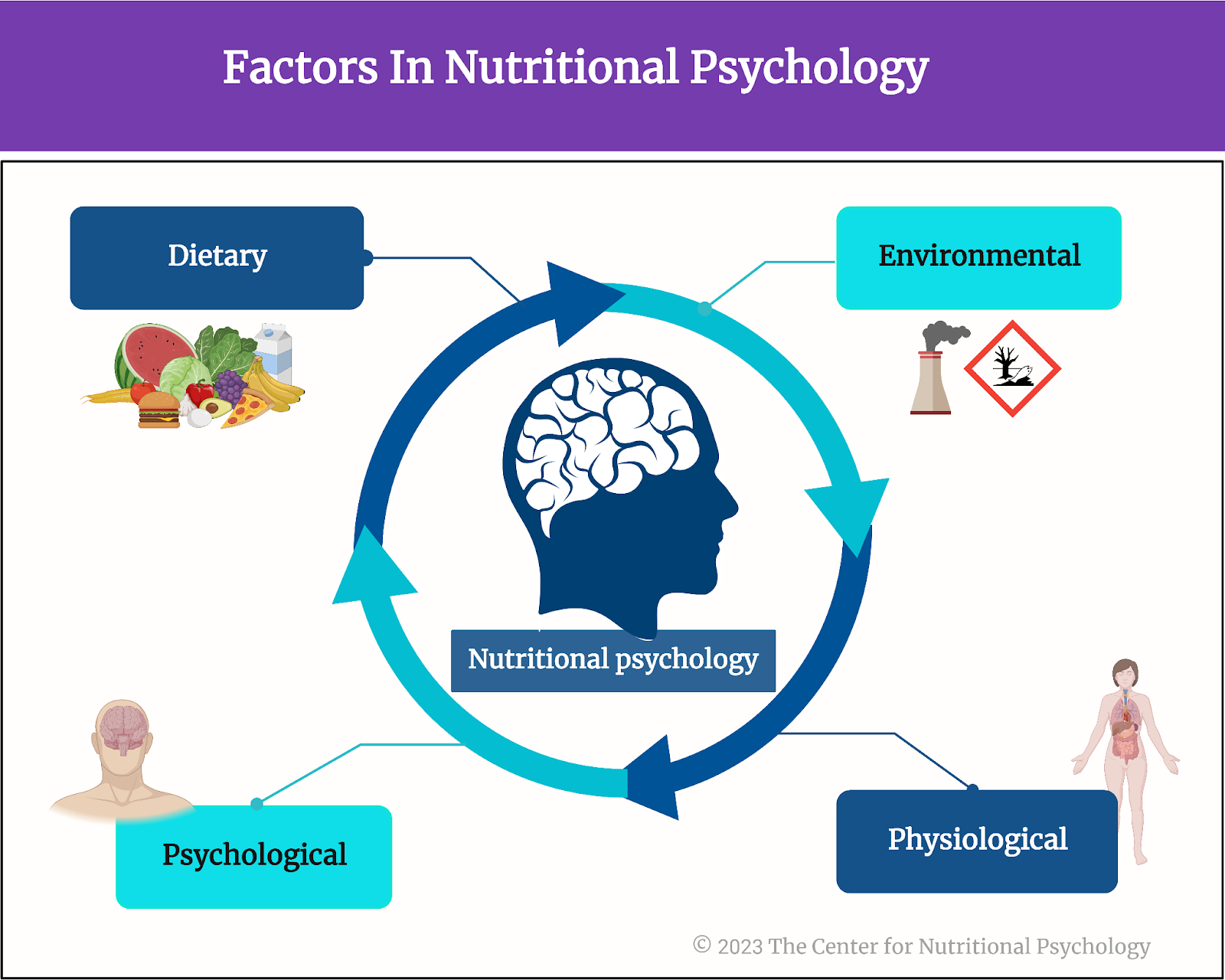

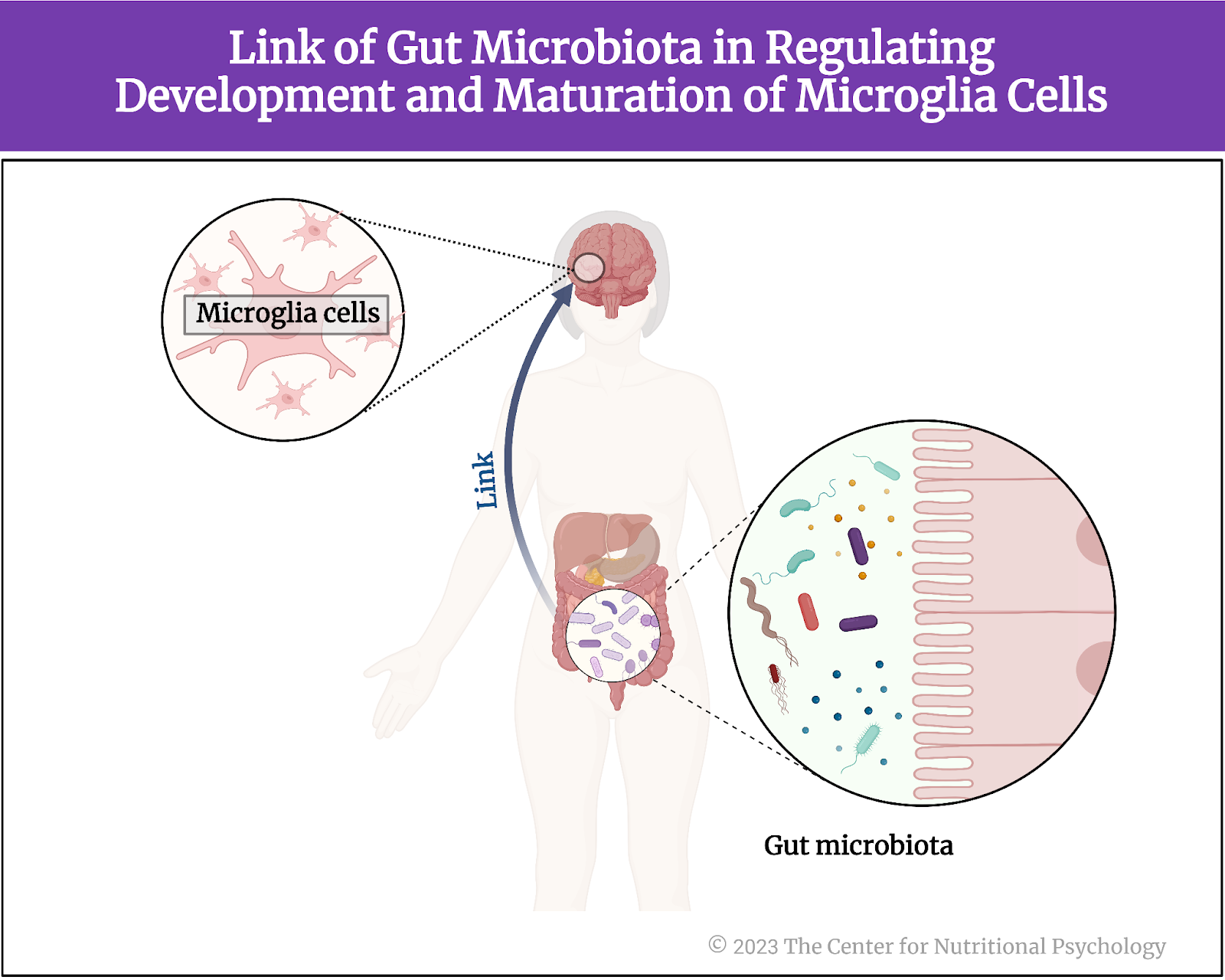

The human gut microbiome, often called gut microbiota or gut flora, is a complex community of trillions of microorganisms that reside in the digestive tract, primarily in the colon. These microorganisms include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes. Gur microbiota is critical in digesting food, absorbing nutrients, and aiding our metabolic activity.

Humans have known for centuries there is a link between our digestive system and how we feel

Gut microbiota helps maintain a balanced and healthy immune system. The composition and diversity of gut microbiota can vary significantly among individuals and can be influenced by factors such as diet, genetics, and lifestyle. It is increasingly recognized as a crucial factor in overall health and well-being (Heiss et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2023).

Microbiota-gut-brain-axis

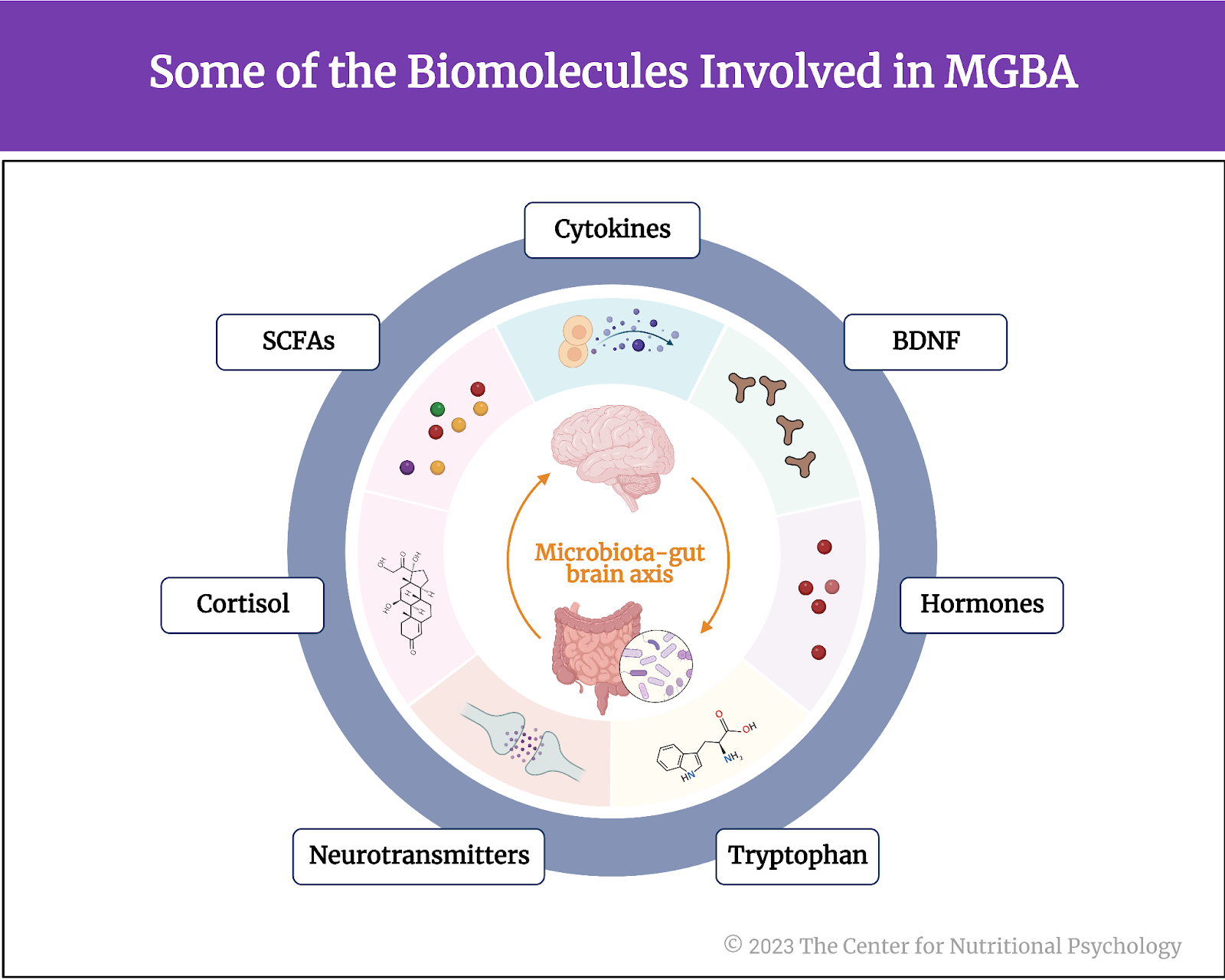

A key pathway through which the link between gut microbiota and well-being is achieved is the microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA). The microbiota-gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system connecting the gut, microbiota, and brain. This axis regulates physiological and psychological processes (Carbia et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023).

Gut microbiota can vary among individuals and is recognized as a crucial factor in overall health and well-being (Heiss et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2023)

The microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) is based on small proteins called cytokines and several other biomolecules, including the hormone cortisol, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan, neurotransmitters, and others (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Some of the Biomolecules involved in MGBA

Emerging studies reveal that the gut microbiota produces substances that can influence the brain’s activity and its responses to stress and emotions. Additionally, the microbiota-gut-brain axis is closely tied to the immune system, influencing the body’s inflammatory responses and potentially contributing to neuroinflammation (Zhu et al., 2023).

Gut microbiota produces substances that influence the brain’s activity and its responses to stress and emotions

These scientific findings suggest that interventions targeting the gut microbiota, such as probiotics and dietary changes, may positively impact mental health and neurological disorders. This can open a new avenue of treatment for mental health issues and possibly other disorders.

The current study

Study author Mireia Valles-Colomer and her colleagues wanted to examine the association between gut microbiota composition and quality of life indicators in the general population. They also wanted to examine links between gut microbiota composition and depression (Valles-Colomer et al., 2019).

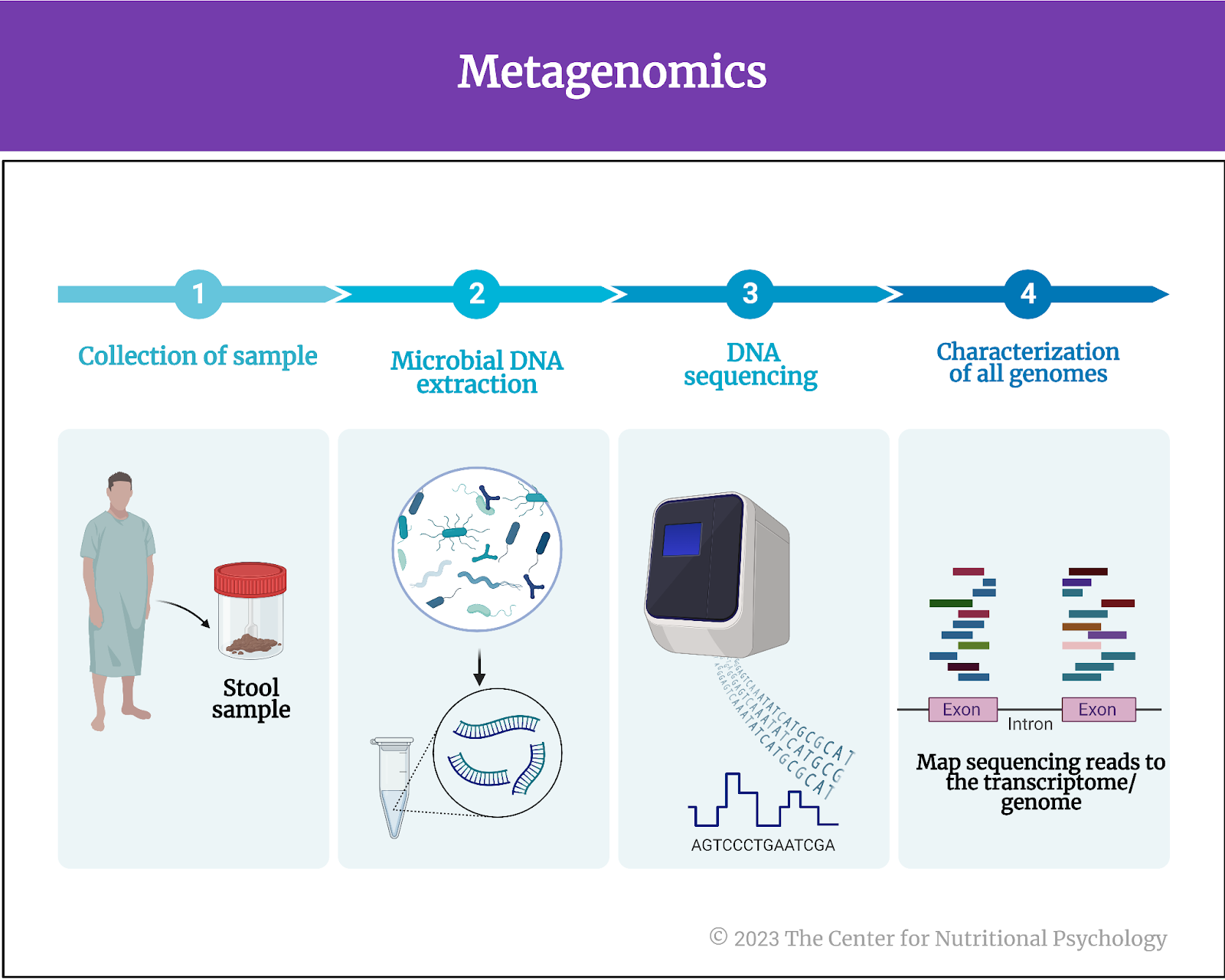

They note that recent advances in genetic sequencing technology allowed researchers to start studying the role of the gut microbiota in a broad range of neurological and psychiatric disorders and diseases. Advancements in the field of metagenomics are a particularly important part of this as it allows relatively easy and noninvasive exploration of human gut microbiota composition.

Recent advances in genetic sequencing technology allows researchers to study the role of microbiota in neurological and psychiatric disorders

Metagenomics

Metagenomics is a field of genetics and microbiology that involves the study of genetic material collected directly from environmental samples, like soil, water, or the human gut, without the need for isolating and cultivating individual organisms. It employs advanced DNA sequencing techniques to analyze and characterize collective genomes of microorganisms in studied samples and their genetic diversity.

In the case of human gut microbiota studies, researchers typically collect stool samples for this purpose. They then use metagenomics techniques to determine the presence, absence, and abundance of different species of microorganisms in the gut microbiota (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Metagenomics

The procedure – the Belgian Flemish Gut Flora project data

The authors of this study analyzed data from two large-group longitudinal studies in Europe. The first set came from the Belgian Flemish Gut Flora Project (FGFP). It contained data from 1054 individuals on gut microbiota and depression as reported by general medical practitioners. The quality of life of these study participants was assessed using the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. This assessment covers eight health concepts – role limitations caused by emotional health problems, social functioning, emotional well-being, vitality, physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical health, body pain, and general health perception. Participants who were using antidepressants but were not diagnosed with depression were excluded from the analysis.

From this group, study authors selected 80 participants with clinically diagnosed depression (40 were using antidepressants) and 70 healthy participants as controls, matched with them on age, sex, body mass index, and stool consistency for in-depth analysis using shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a method that involves sequencing all the genetic material present in a microbial community sample, providing a comprehensive view of the genes and organisms within that community.

The Lifelines Cohort data and controls

Researchers used another sample to verify their findings – the Lifelines Cohort. The Lifelines Cohort is a large-scale, three-generation longitudinal study in the Netherlands. It contains a large amount of medical and psychological data from over 167,000 participants so far. The Lifelines cohort study was started in 2006 and aimed to include 10% of the northern population of the Netherlands of all ages. The authors of the Lifelines Cohort study hope to be able to follow these individuals for 30 years and collect follow-up data during this time.

In this study, the authors used data from 1063 individuals from the Lifeline Cohort. The quality of life of this group was assessed in the same way as in the Belgian sample. Participants self-reported depression. Researchers asked participants to indicate the disorders they have or have had, and depression was on the list. Participants also reported on their use of antidepressants in the last three months.

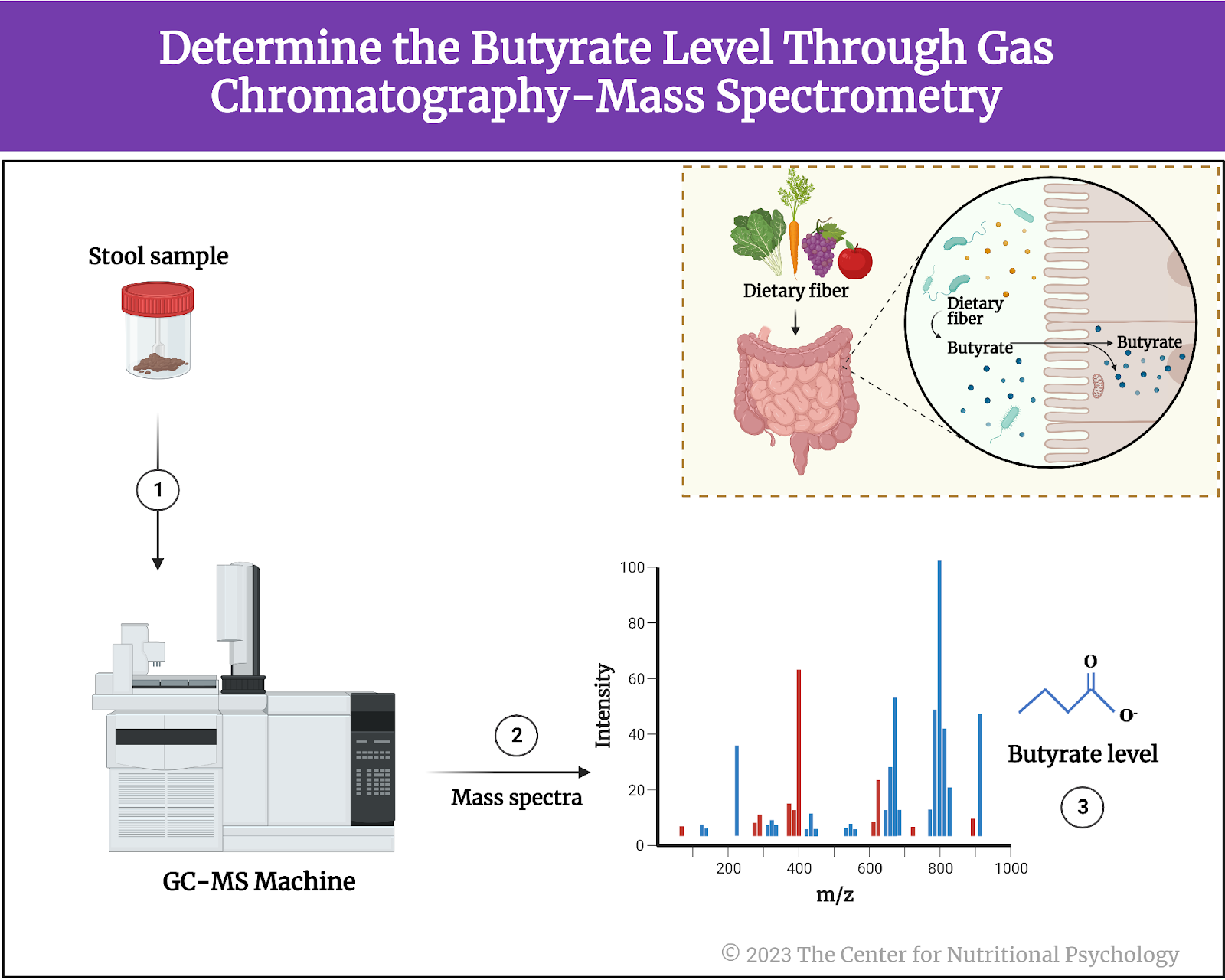

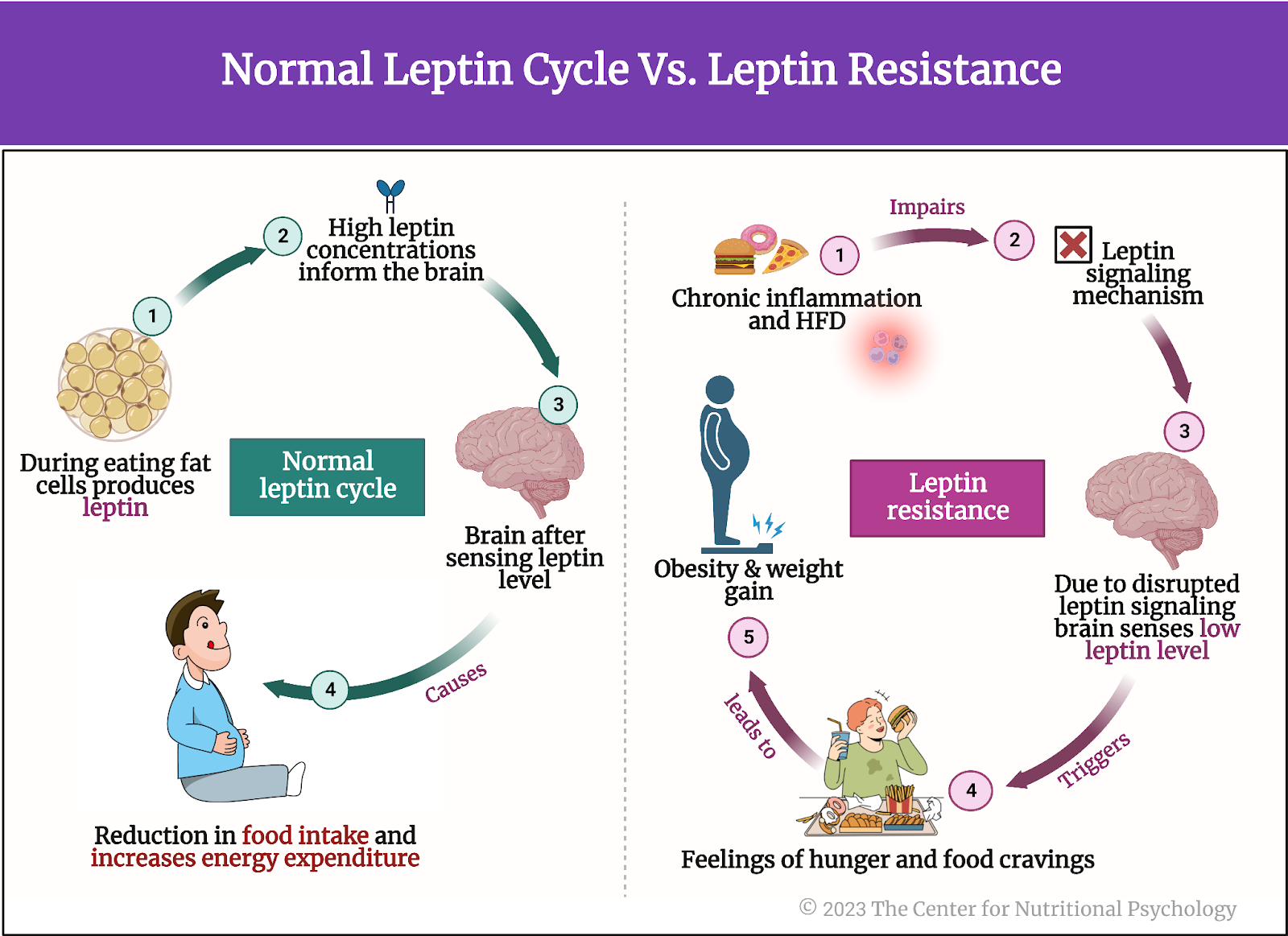

The study authors used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to determine butyrate levels in stool samples from this dataset. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid produced by certain species of bacteria in the gut during the fermentation of dietary fiber (see Figure 3). It is an important energy source for the cells lining the colon and helps maintain their integrity and function. Additionally, it has anti-inflammatory properties and has been associated with various health benefits. Butyrate potentially reduces the risk of inflammatory bowel diseases and promotes overall gut health.

Figure 3. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate

Additionally, study authors collected and sequenced seven stool samples from patients suffering from major depressive disorder resistant to treatment. Participants in this sample were diagnosed with moderate-to-severe depression and inadequate response to at least two therapies with antidepressants. Inadequate response means that symptoms of depression persist after treatment.

Gut microbiota composition was related to quality of life

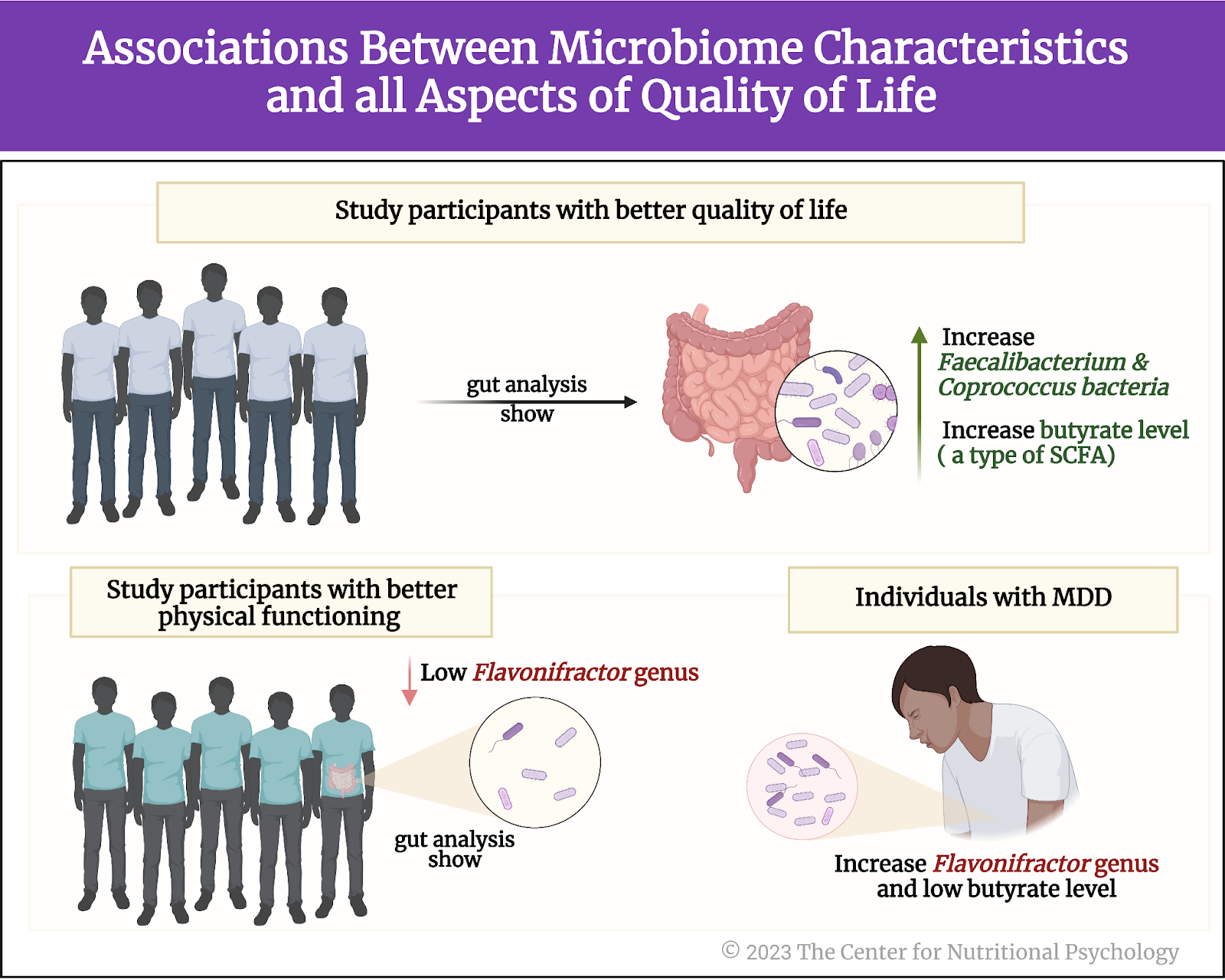

Results revealed multiple associations between microbiome characteristics and all aspects of quality of life (see Figure 4). Study participants with better quality of life indicators tended to have more Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus bacteria in their guts. Those with better physical functioning tended to have fewer bacteria from the Flavonifractor group of species (genus). This group of bacterial species was also increased in individuals suffering from major depressive disorder (MDD).

Figure 4. Associations between microbiome characteristics and all aspects of quality of life (as outlined earlier)

Study authors note that Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus bacteria produce the short-chain fatty acid butyrate. Butyrate levels in the gut are generally reduced in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease and those with depression. They examined the Lifelines cohort data to verify this finding, and the results showed that the abundance of these bacteria is indeed associated with butyrate concentrations in the stool.

Butyrate levels in the gut are reduced in those with inflammatory bowel disease and depression

Coprococcus and Dialister bacteria are depleted in the guts of individuals suffering from depression

Study authors identified 4 groups of bacterial species that were consistently depleted in individuals suffering from depression (depleted in this case, means that they are present in numbers significantly lower than those found in typical healthy individuals).

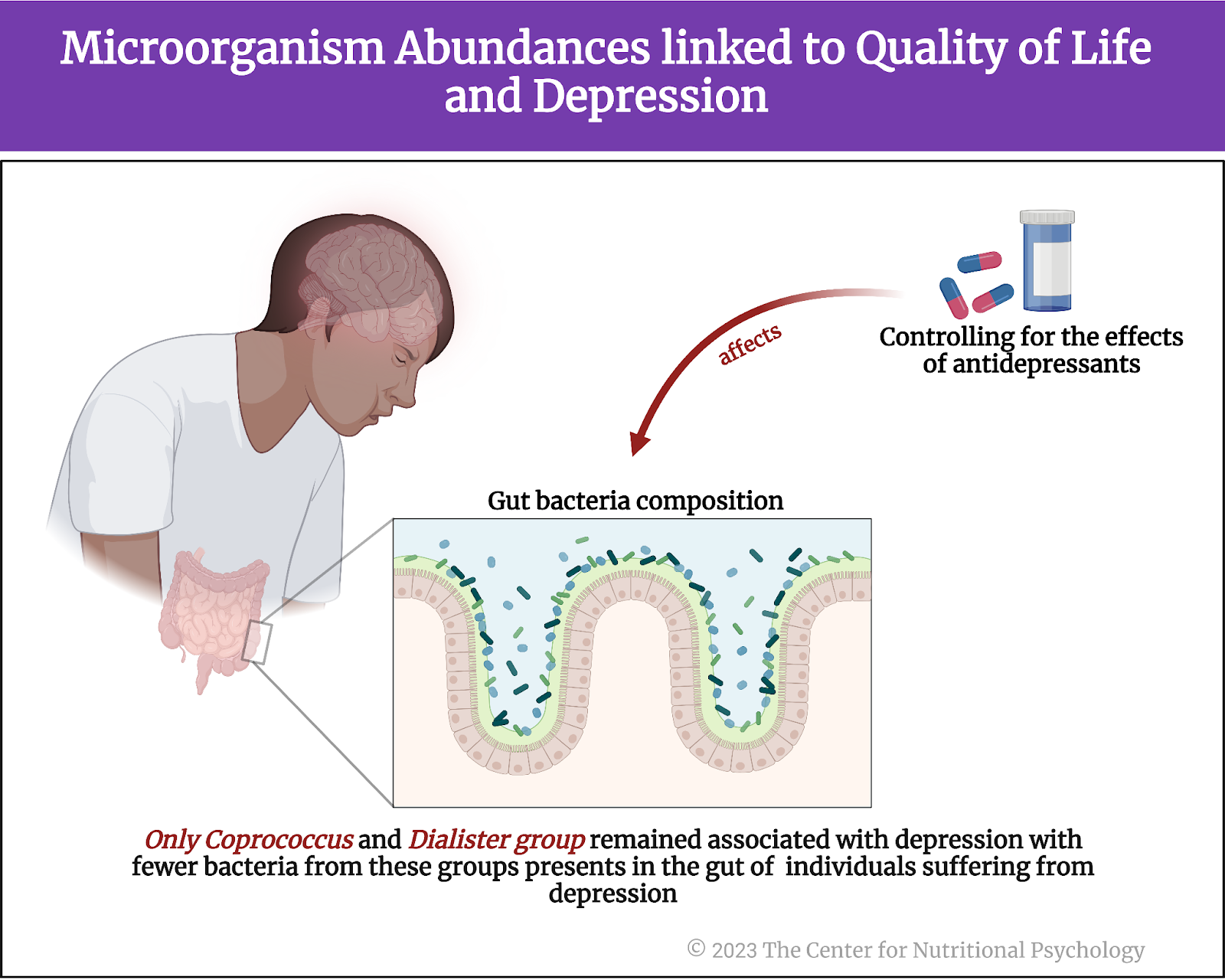

However, further analyses revealed that antidepressants can substantially affect the composition of gut bacteria. When study authors controlled for the use of antidepressants, only Coprococcus and Dialister groups of species remained associated with depression. There were significantly fewer bacteria from these groups in the guts of individuals suffering from depression than healthy individuals (see Figure 5). This finding was held in the Flemish Gut Flora and the Lifeline Cohort data.

Figure 5. Microorganism abundances linked to Quality of Life and Depression

Bacteria producing 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid are more abundant in individuals with better social functioning

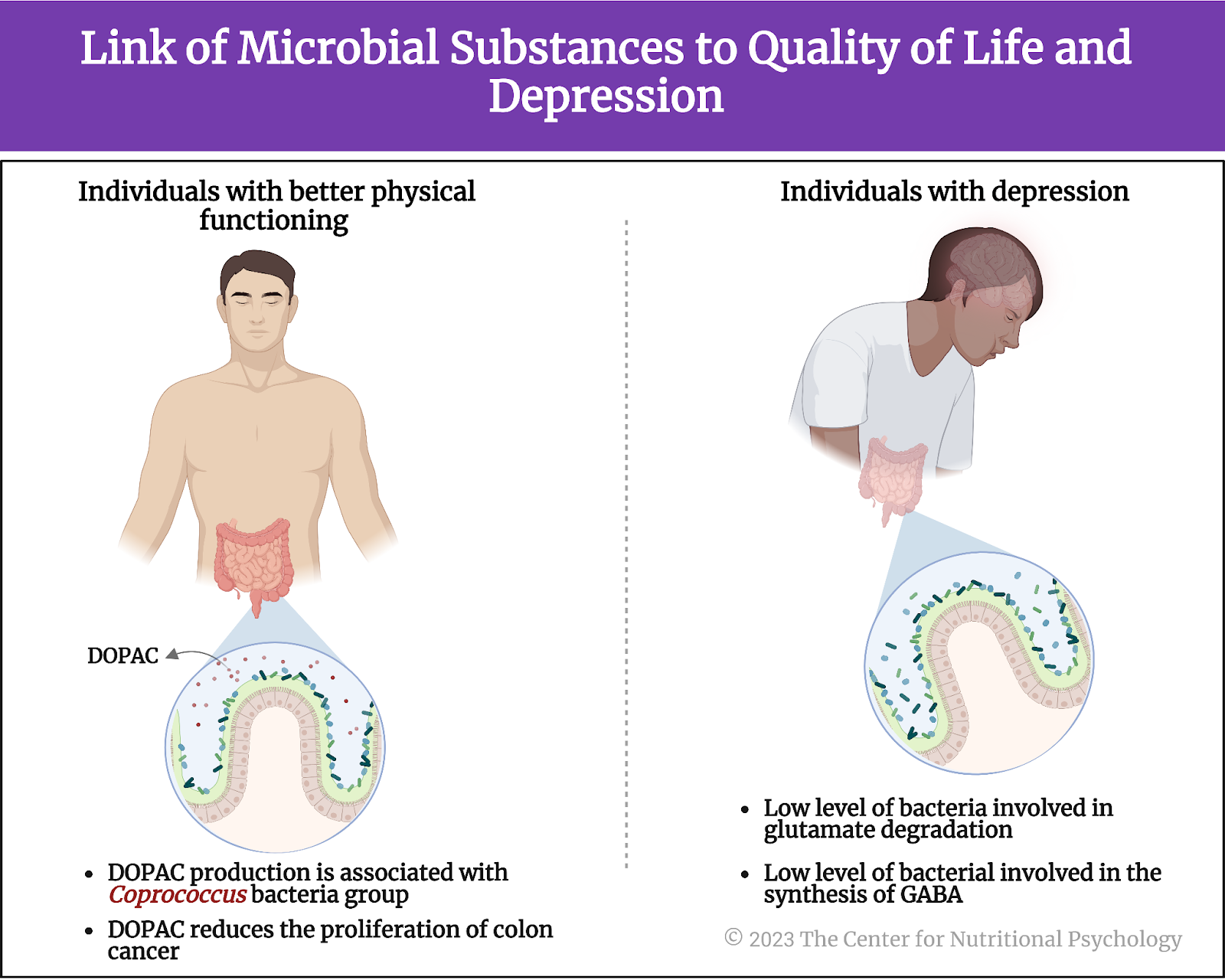

Next, the study authors examined the gut-brain modules, i.e., they looked for groups of bacteria that produce substances that could affect mental states and their links to quality-of-life indicators. These analyses showed that bacteria producing 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) were more abundant in participants with better social functioning scores.

The potential for producing this substance was the most strongly associated with Coprococcus group of bacteria. DOPAC is produced from dopamine, an important neurotransmitter, and researchers believe it can reduce the proliferation of colon cancer cells. Reduced DOPAC levels are a potential biomarker of Parkinson’s disease (Valles-Colomer et al., 2019).

Bacteria involved in the degradation of glutamate and production of GABA tended to be depleted in participants with depression

Additionally, bacteria involved in glutamate degradation tended to be depleted in participants with depression. Glutamate is an amino acid that plays a role in various metabolic and signaling pathways in the body. However, it is also the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. This means that it increases the likelihood of neurons generating a nerve impulse.

Microorganisms involved in synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) also tended to be depleted in participants with depression. GABA is an important inhibitory neurotransmitter. It makes neurons less likely to fire a nerve impulse (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Link of microbial substance to the quality of life and depression

Conclusion

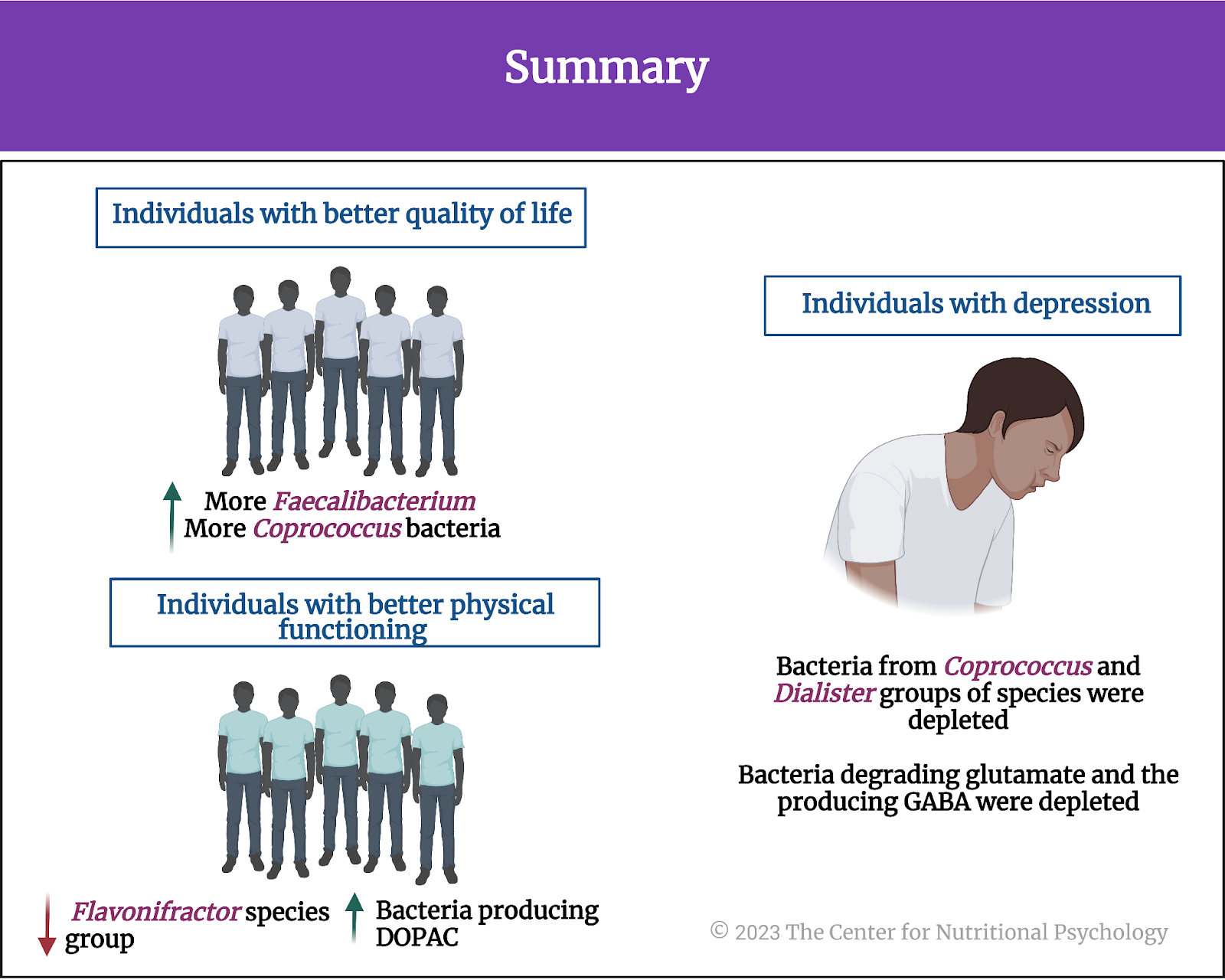

Overall, the analysis of two large sets of gut microbiome samples from two different (although neighboring) countries confirmed specific links between gut microbiota composition and mental health indicators. Individuals with better quality of life indicators tended to have more Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus bacteria in their gut. Those with better physical functioning tended to have fewer bacteria from the Flavonifractor species group. Bacteria from Coprococcus and Dialister groups of species tended to be much less present in the guts of individuals suffering from depression.

Bacteria capable of producing 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid or DOPAC were more abundant in participants with better social functioning scores. DOPAC is produced from dopamine, an important neurotransmitter in the human body, and it plays various important roles in the body’s functioning. Bacteria involved in the degradation of glutamate and the production of GABA, two important neurotransmitters, tended to be depleted in individuals with depression (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Summary

While these findings are only correlational and do not allow for cause-and-effect conclusions, future research can be expected to map causal pathways responsible for the observed associations. This could open a new avenue of mental health treatments to achieve improved mental outcomes by affecting the gut or adjusting gut microbiota composition. It is also not hard to imagine scientists in the future using genetic techniques to create microorganisms that could influence mental health or mental states when placed in the gut.

The paper “The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression” was authored by Mireia Valles-Colomer, Gwen Falony, Youssef Darzi, Ettje F. Tigchelaar, Jun Wang , Raul Y. Tito, Carmen Schiweck, Alexander Kurilshikov , Marie Joossens, Cisca Wijmenga, Stephan Claes, Lukas Van Oudenhove, Alexandra Zhernakova, Sara Vieira-Silva , and Jeroen Raes.

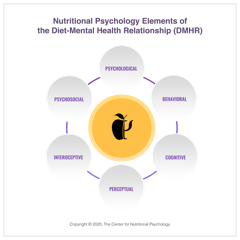

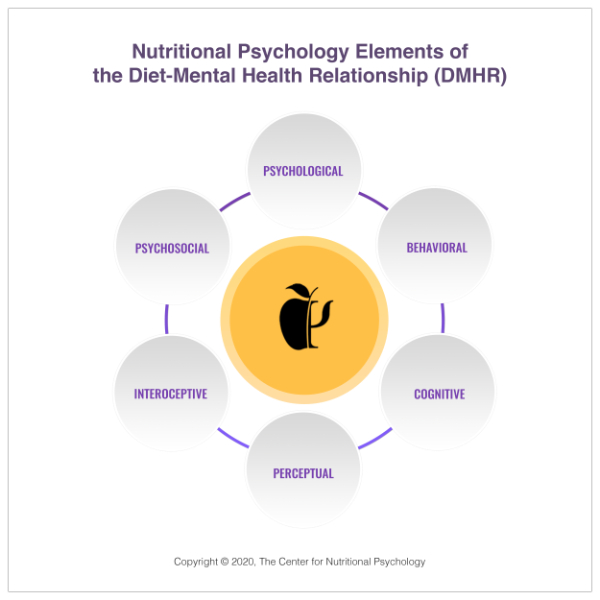

To learn more about this topic,, CNP has developed two university-level continuing education courses exploring the evidence based interconnections in the microbiota-gut-brain axis diet-mental health relationship (MGBA-DMHR). See our course pages here.

References

Carbia, C., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Iannone, F., García-cabrerizo, R., Boscaini, S., Berding, K., Strain, C. R., Clarke, G., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2023). The Microbiome-Gut-Brain axis regulates social cognition & craving in young binge drinkers. EBioMedicine, (In press), 104442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104442

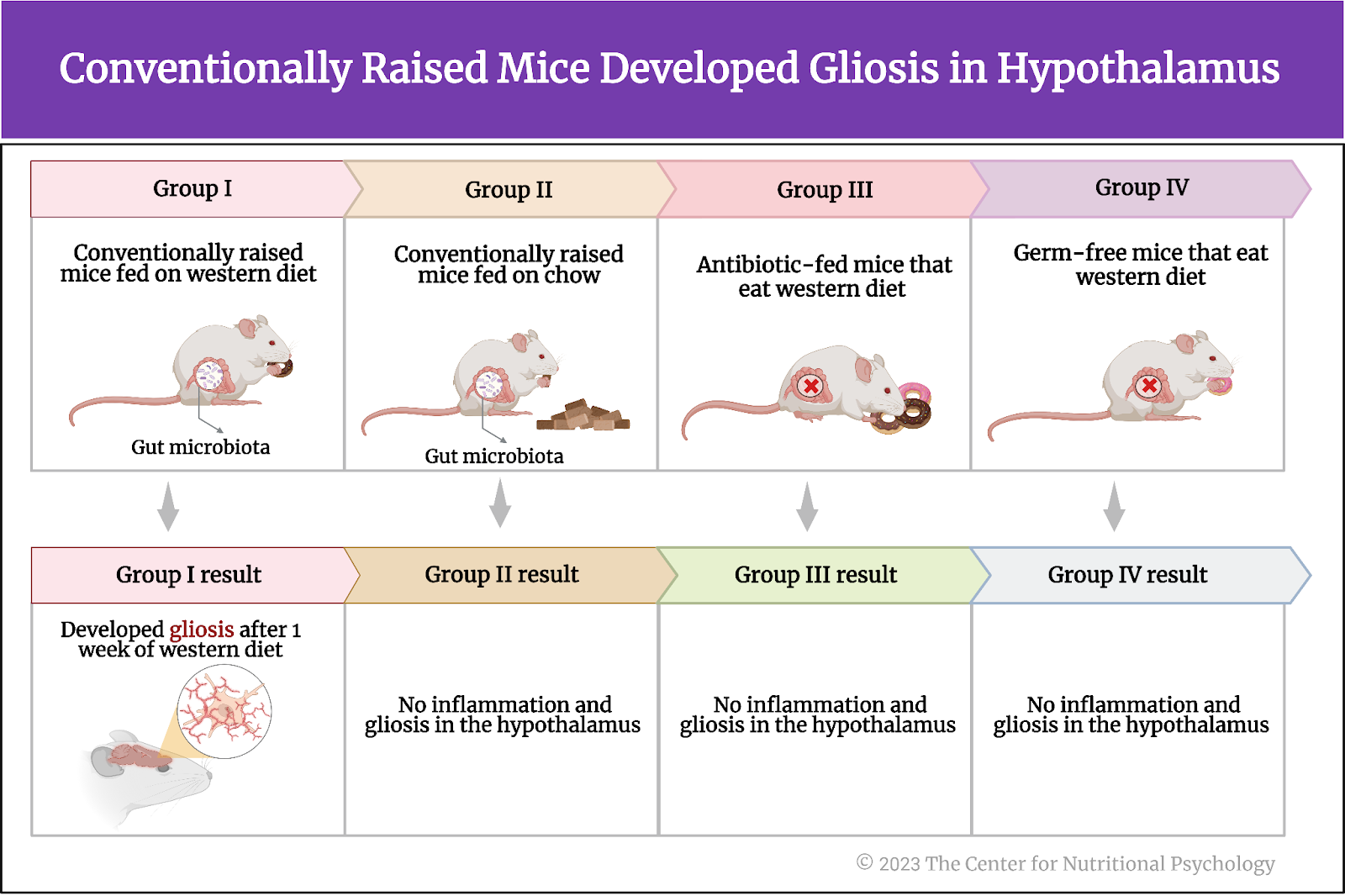

Heiss, C. N., Mannerås-Holm, L., Lee, Y. S., Serrano-Lobo, J., Håkansson Gladh, A., Seeley, R. J., Drucker, D. J., Bäckhed, F., & Olofsson, L. E. (2021). The gut microbiota regulates hypothalamic inflammation and leptin sensitivity in Western diet-fed mice via a GLP-1R-dependent mechanism. Cell Reports, 35(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109163

Valles-Colomer, M., Falony, G., Darzi, Y., Tigchelaar, E. F., Wang, J., Tito, R. Y., Schiweck, C., Kurilshikov, A., Joossens, M., Wijmenga, C., Claes, S., Van Oudenhove, L., Zhernakova, A., Vieira-Silva, S., & Raes, J. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology, 4(4), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x

Zhu, X., Sakamoto, S., Ishii, C., Smith, M. D., Ito, K., Obayashi, M., Unger, L., Hasegawa, Y., Kurokawa, S., Kishimoto, T., Li, H., Hatano, S., Wang, T. H., Yoshikai, Y., Kano, S. ichi, Fukuda, S., Sanada, K., Calabresi, P. A., & Kamiya, A. (2023). Dectin-1 signaling on colonic γδ T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses. Nature Immunology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01447-8

1. NP Elements Diagram

1. NP Elements Diagram