- A large epidemiological study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics reported an association between the consumption of ultra-processed food and chronic insomnia

- Overall, 19.4% of individuals had symptoms of chronic insomnia, and ultra-processed foods were 16% of participants’ daily food intake

- However, increasing ultra-processed food intake by 10% was associated with 9% higher odds of suffering from chronic insomnia among men and 5% higher odds among women

We have all experienced situations when we have trouble getting good sleep. This can happen when we are excited, when something troubles us, when our sleeping arrangements are uncomfortable, and under many other circumstances. However, some people have constant difficulties with getting good sleep. This is called chronic insomnia.

What is chronic insomnia?

Chronic insomnia is a sleep disorder characterized by difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up too early, occurring at least three nights per week for three months or more (Insomnia – What Is Insomnia? 2022). Common causes of chronic insomnia include stress, anxiety, depression, chronic pain, and certain medications or substances.

This condition leads to chronically poor sleep quality and insufficient rest, which can significantly impair daytime functioning, including concentration, mood, and overall productivity (Drake et al., 2003; Roberts et al., 2008). Chronic insomnia is also associated with an increased risk of developing other health problems, such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes (Sofi et al., 2014; Vgontzas et al., 2009).

Insomnia and diet

Diet is an important determinant of health and chronic disease risk. Many studies report links between dietary habits and risks of specific diseases or adverse health outcomes (Camprodon-Boadas et al., 2024; Hedrih, 2024; Huang et al., 2023).

Diet is an important determinant of health and chronic disease risk.

Recently, industrially processed foods have started attracting researchers’ interest. This is especially the case with ultra-processed foods. Ultra-processed foods are formulations made mostly or entirely from derived substances and various additives with few intact unprocessed or minimally processed food components (Hedrih, 2023; Monteiro et al., 2019).

These foods typically contain artificial additives, preservatives, and flavor enhancers. Additives include dyes, color stabilizers, non-sugar sweeteners, de-foaming, anti-caking or glazing agents, emulsifiers, or humectants. Examples of ultra-processed foods include instant noodles, artificial sweeteners, artificially sweetened beverages, sugary cereals, microwaveable meals, reconstituted meat products, sweet and savory packaged snacks, pre-prepared frozen dishes, and soft drinks (Hedrih, 2023) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of ultra-processed foods

Many studies linked the consumption of ultra-processed foods with increased risks of various health conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, depression, anxiety, and general risk of death from different causes (e.g., Lane et al., 2024). Some even propose that ultra-processed foods be classified as addictive substances (Gearhardt et al., 2023; Hedrih, 2023)

The current study

Study author Pauline Duquenne and her colleagues wanted to assess the association between the consumption of ultra-processed food and chronic insomnia. They hypothesized that a greater intake of ultra-processed foods would be associated with increased insomnia symptoms (Duquenne et al., 2024).

These authors analyzed data from NutriNet-Santé, an ongoing online study that started in France in 2009. NutriNet-Santé participants are adults who can comprehend written French. The data used in this analysis came from 38,570 participants. Their average age was 50 years, and 77% were females.

When they are included in the study and at regular intervals thereafter, NutriNet-Santé participants complete a battery of questionnaires about their lifestyle profiles, body measurements, physical activity, and health status.

Participants provided their dietary intake data every six months. On these occasions, the study asks them to complete three 24-hour dietary records over a two-week period. The days when dietary intake was recorded were not on consecutive days (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study Procedure (Duquenne et al., 2024)

Aside from this, the current analysis utilized assessments of participants’ chronic insomnia symptoms and their sociodemographic data.

Chronic insomnia is associated with anxiety, depression, and female gender

Results showed that 19.4% of participants had symptoms of chronic insomnia. These individuals were also more likely to show symptoms of depression and anxiety. Participants with chronic insomnia were more often females. Females were 84% of the chronic insomnia group and 75% of participants without chronic insomnia.

Because the sample was very large, associations with many other demographic and lifestyle factors were also detected, but these associations tended to be very small.

Individuals suffering from chronic insomnia tended to consume more ultra-processed foods

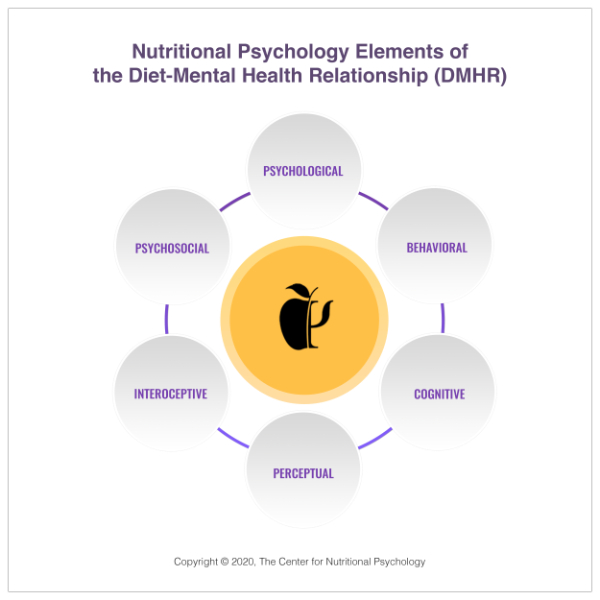

Ultra-processed foods constituted 16% of participants’ daily food intake. However, participants with chronic insomnia tended to consume more of this type of food. Statistical analysis showed that a 10% increase in daily intake of ultra-processed food corresponded to a 6% higher odds of suffering from chronic insomnia.

Participants with chronic insomnia tended to consume more ultra-processed foods.

This percentage differed somewhat between the sexes. Among men, a 10% higher daily intake of ultra-processed foods corresponded to a 9% higher odds of suffering from chronic insomnia. The increase in odds was 5% among women (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Study findings (Duquenne et al., 2024)

Conclusion

Using a very large sample from the French-speaking population, this study demonstrates a link between ultraprocessed food consumption and the risk of chronic insomnia. Although the increased risk reported in this study is only slight, this finding adds to the growing body of evidence associating the consumption of ultra-processed foods with adverse health outcomes.

However, it should be noted that the design of this study does not allow any cause-and-effect conclusions to be drawn from the results. While it is possible that increased consumption of ultra-processed food increases the risk of chronic insomnia, it is also possible that chronic insomnia or factors leading to chronic insomnia make a person more likely to consume ultra-processed foods (e.g., because they are readily available or highly palatable). Further studies are needed to clarify the nature of the observed links.

The paper “The association between ultra-processed food consumption and chronic insomnia in the NutriNet-Santé Study” was authored by Pauline Duquenne, Julia Capperella, Léopold K. Fezeu, Bernard Srour, Giada Benasi, Serge Hercberg, Mathilde Touvier, Valentina A. Andreeva, and Marie-Pierre St-Onge.

References

Camprodon-Boadas, P., Gil-Dominguez, A., De La Serna, E., Sugranyes, G., Lázaro, I., & Baeza, I. (2024). Mediterranean Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrition Reviews, nuae053. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuae053

Drake, C. L., Roehrs, T., & Roth, T. (2003). Insomnia causes, consequences, and therapeutics: An overview. Depression and Anxiety, 18(4), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10151

Duquenne, P., Capperella, J., Fezeu, L. K., Srour, B., Benasi, G., Hercberg, S., Touvier, M., Andreeva, V. A., & St-Onge, M.-P. (2024). The association between ultra-processed food consumption and chronic insomnia in the NutriNet-Santé Study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, S2212267224000947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2024.02.015

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Hedrih, V. (2023). Scientists Propose that Ultra-Processed Foods be Classified as Addictive Substances. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/scientists-propose-that-ultra-processed-foods-be-classified-as-addictive-substances/

Hedrih, V. (2024, March 4). Researchers Identify Neural Pathways Transmitting Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hunger. Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/researchers-identify-neural-pathways-transmitting-anti-inflammatory-effects-of-hunger/

Huang, Y., Chen, Z., Chen, B., Li, J., Yuan, X., Li, J., Wang, W., Dai, T., Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wang, P., Guo, J., Dong, Q., Liu, C., Wei, Q., Cao, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 381, e071609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071609

Insomnia – What Is Insomnia? | NHLBI, NIH. (2022, March 24). https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/insomnia

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., Ashtree, D. N., McGuinness, A. J., Gauci, S., Baker, P., Lawrence, M., Rebholz, C. M., Srour, B., Touvier, M., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Segasby, T., & Marx, W. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Roberts, R. E., Roberts, C. R., & Duong, H. T. (2008). Chronic Insomnia and Its Negative Consequences for Health and Functioning of Adolescents: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.016

Sofi, F., Cesari, F., Casini, A., Macchi, C., Abbate, R., & Gensini, G. (2014). Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 21, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487312460020

Vgontzas, A. N., Liao, D., Pejovic, S., Calhoun, S., Karataraki, M., & Bixler, E. O. (2009). Insomnia With Objective Short Sleep Duration Is Associated With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 32(11), 1980–1985. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-0284