Stress is inevitable, but it can disturb our body’s physiological signaling mechanisms when it becomes chronic. These mechanisms are interlinked with the Microbiota Gut-brain axis (MGBA) and influence the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR) in many ways. Being a major immune organ and highly colonized with the microbiome, our gut experiences certain immune inflammatory responses due to stress, which affect the gut microbiome composition and contribute to the onset of depression and anxiety.

A new study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins has strengthened our understanding of the role of specific gut immune cells in microbiota composition and influencing the brain’s responsiveness to stress. This early-stage experiment on mice found that a specific type of white blood cells, gamma-delta T lymphocytes, play a key role in the cellular mechanism leading to adverse behavioral changes under chronic stress. After chronic stress, some mice in the experiment developed social avoidance behavior, i.e., they started avoiding contact with other mice. These mice had reduced diversity of microorganisms in their guts and increased concentrations of gamma-delta T lymphocytes in their intestines and in the membranes surrounding their brains. Under equal chronic stress conditions, mice without gamma-delta T lymphocytes did not develop social avoidance behavior (Zhu et al., 2023). The study was published in Nature Immunology.

After chronic stress, some mice in the experiment started avoiding contact with other mice. They had reduced microbial diversity and increased concentrations of gamma-delta T lymphocytes in their gut and surrounding their brain

Chronic stress

Chronic stress is a consistent sense of feeling pressured and overwhelmed over a long period of time. There are many possible sources of chronic stress in modern society. These include bad living conditions and homelessness, bad family and social relations, negative interactions between work and family, adverse work conditions, illness, and many others (Armon et al., 2014; Goodman et al., 1991; Tsukerman et al., 2020). Chronic stress slowly drains a person’s psychological energy and has damaging effects on both health and well-being.

Chronic stress and the gut microbiota

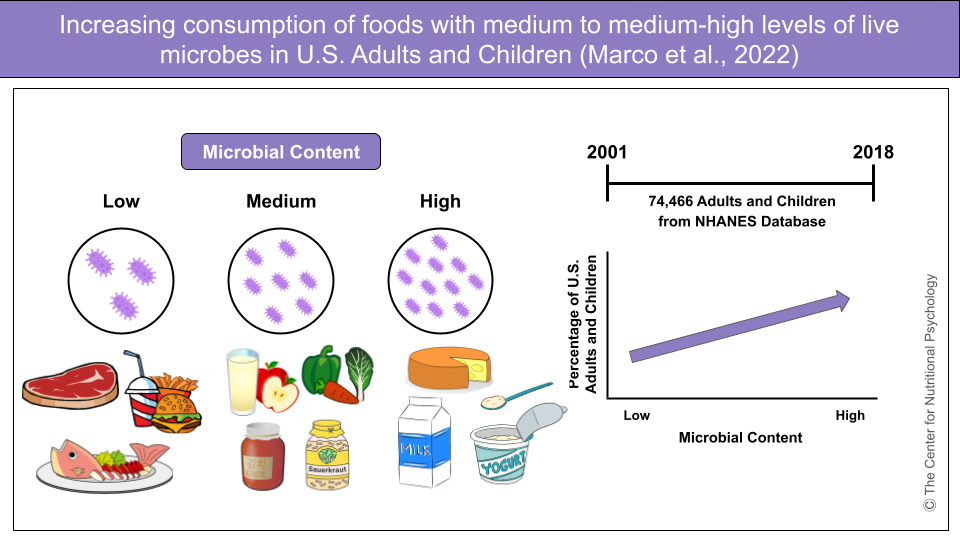

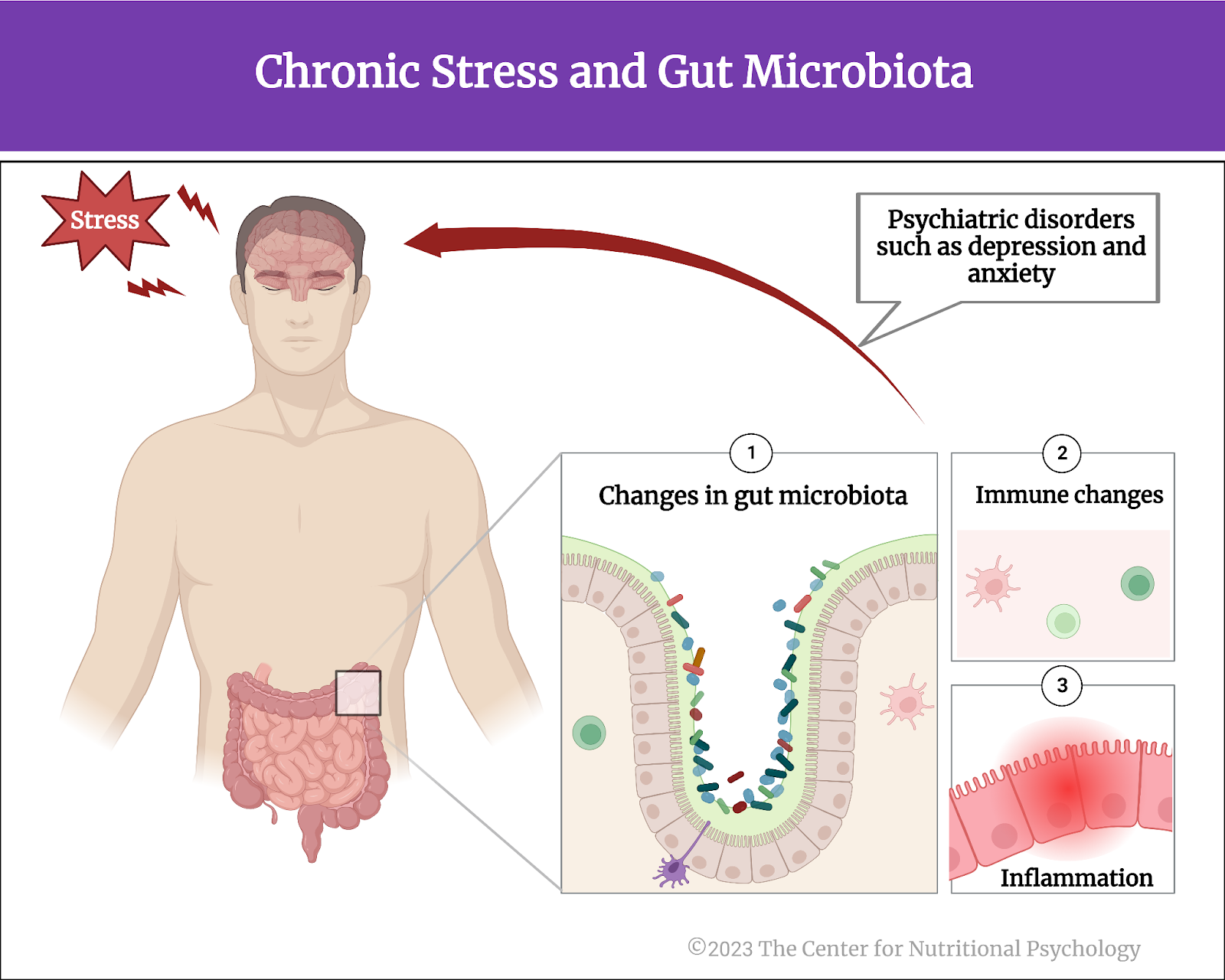

Physiologically, chronic stress induces immune changes and inflammation, leading to psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety (Hodes et al., 2014). These immune changes include changes to the gut microbiota – the trillions of microorganisms that live in the human intestinal tract (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chronic stress leads to immune changes, inflammation, depression, and anxiety

Gut microorganisms play a key role in digesting food, but they are also incredibly important for various other processes, such as the differentiation of certain immune cells (Zhu et al., 2023). Differentiation is when immature and unspecialized cells transform into specialized, mature cells that perform specific bodily functions. It is one of the critical processes of life. When a person is under stress, the body reacts with inflammation, that in turn affects the composition of microorganisms in the gut but also creates physiological changes that reach the brain and affect cognition and behavior.

Due to this, studying physiological changes associated with chronic stress is very important for understanding the development of the most common psychiatric disorders and finding effective ways to treat them. However, research ethics and practical considerations impose very strict limits on what types of studies can be conducted on humans. That is why studies of the physiology and biochemistry of chronic stress are often done on animals, particularly mice, using specific research protocols. One research protocol used to induce chronic stress in mice for research purposes is the chronic social defeat stress protocol.

What is chronic social defeat stress?

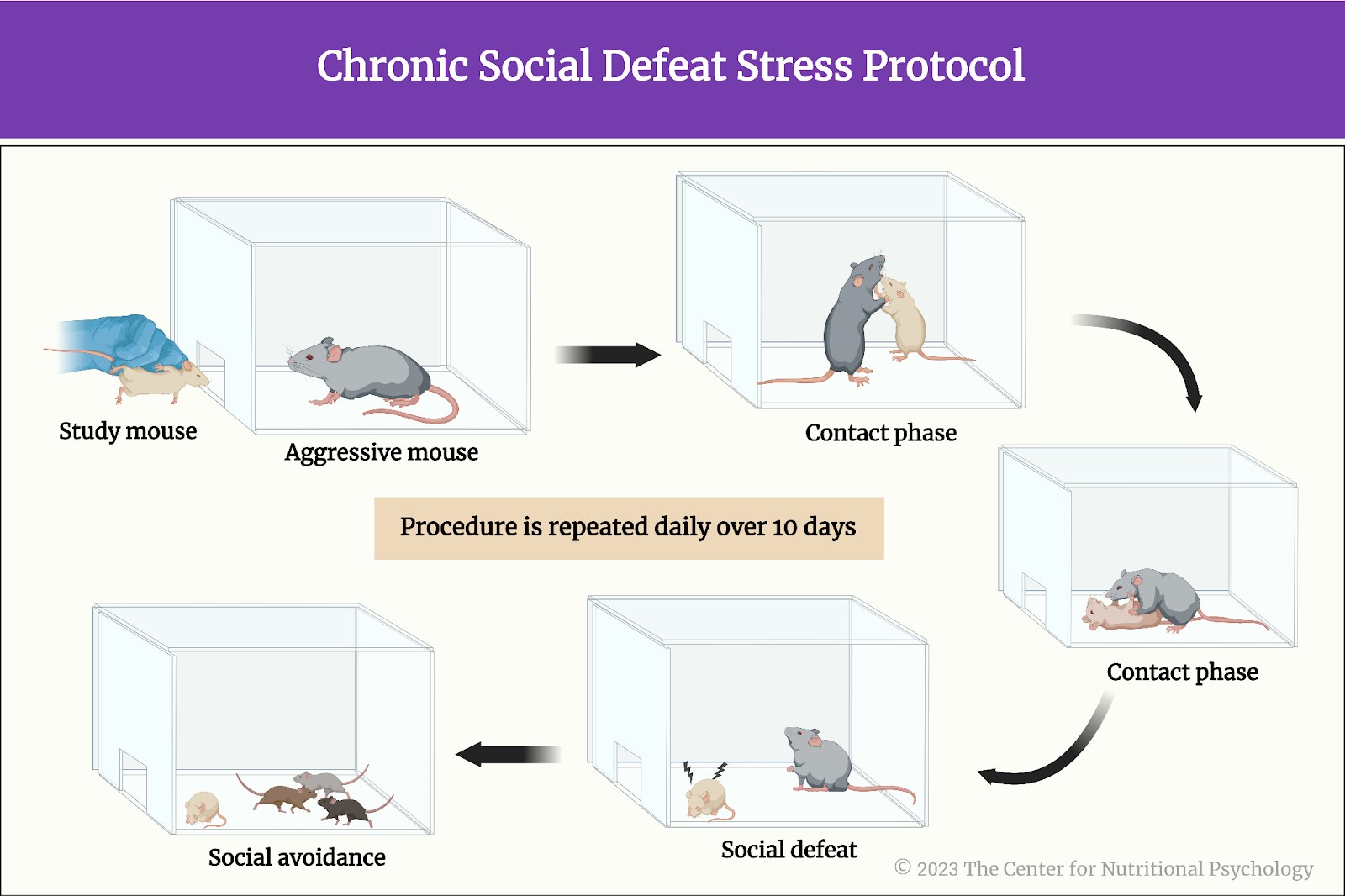

Chronic social defeat stress is a protocol (procedure) in which a mouse is exposed to a larger aggressive mouse in an enclosed space. This is followed by a confrontation between the two mice in which the mouse undergoing this treatment is defeated and forced into a subordinate position (social defeat). Typically, this procedure is repeated daily over ten days (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chronic Social Defeat Stress Protocol

The chronic social defeat stress protocol produces effects similar to depression in exposed mice. It also produces a number of other easily detectable effects such as increased weight of spleen of these mice, lower preference for sucrose, and others. That is why it is extensively used in research on mice (Golden et al., 2011).

The chronic social defeat stress protocol produces effects similar to depression in exposed mice.

The current study

Study author Xiaolei Zhu and his colleagues wanted to explore the cellular mechanisms behind social avoidance behaviors caused by chronic stress. They were particularly interested in the role a specific type of white blood cell called the gamma-delta T lymphocyte has in these changes and in the changes in the composition of gut microorganisms caused by stress.

What are gamma-delta T lymphocytes?

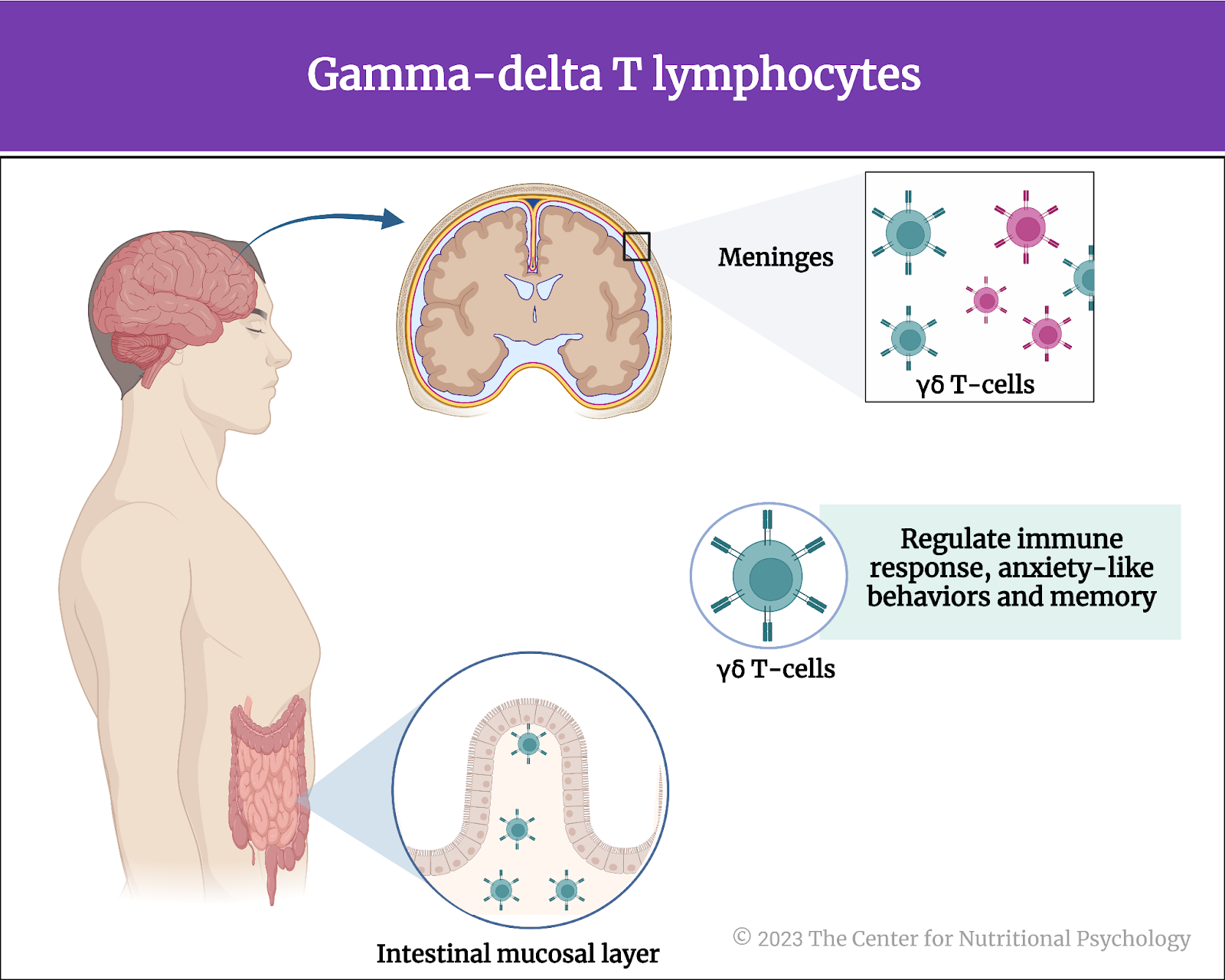

Gamma-delta T lymphocytes (γδ T-cells) are a specific type of white blood cells in the body. Still, they are found in high concentrations in various mucosal tissues called meninges, including intestines and membranes surrounding the brain. Lymphocytes are involved in the body’s immune responses. Studies have shown that gamma-delta T lymphocytes located in the meninges regulate anxiety-like behaviors and memory. Furthermore, research indicated that gamma-delta T lymphocytes in the intestines could travel to the meninges under certain conditions. This has led scientists to assume that these gamma-delta T lymphocytes from the gut may be involved in brain function changes when inflammation occurs (Zhao et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2023) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gamma-delta T lymphocytes are in intestinal mucosal tissue and membranes around the meninges.

The experiment

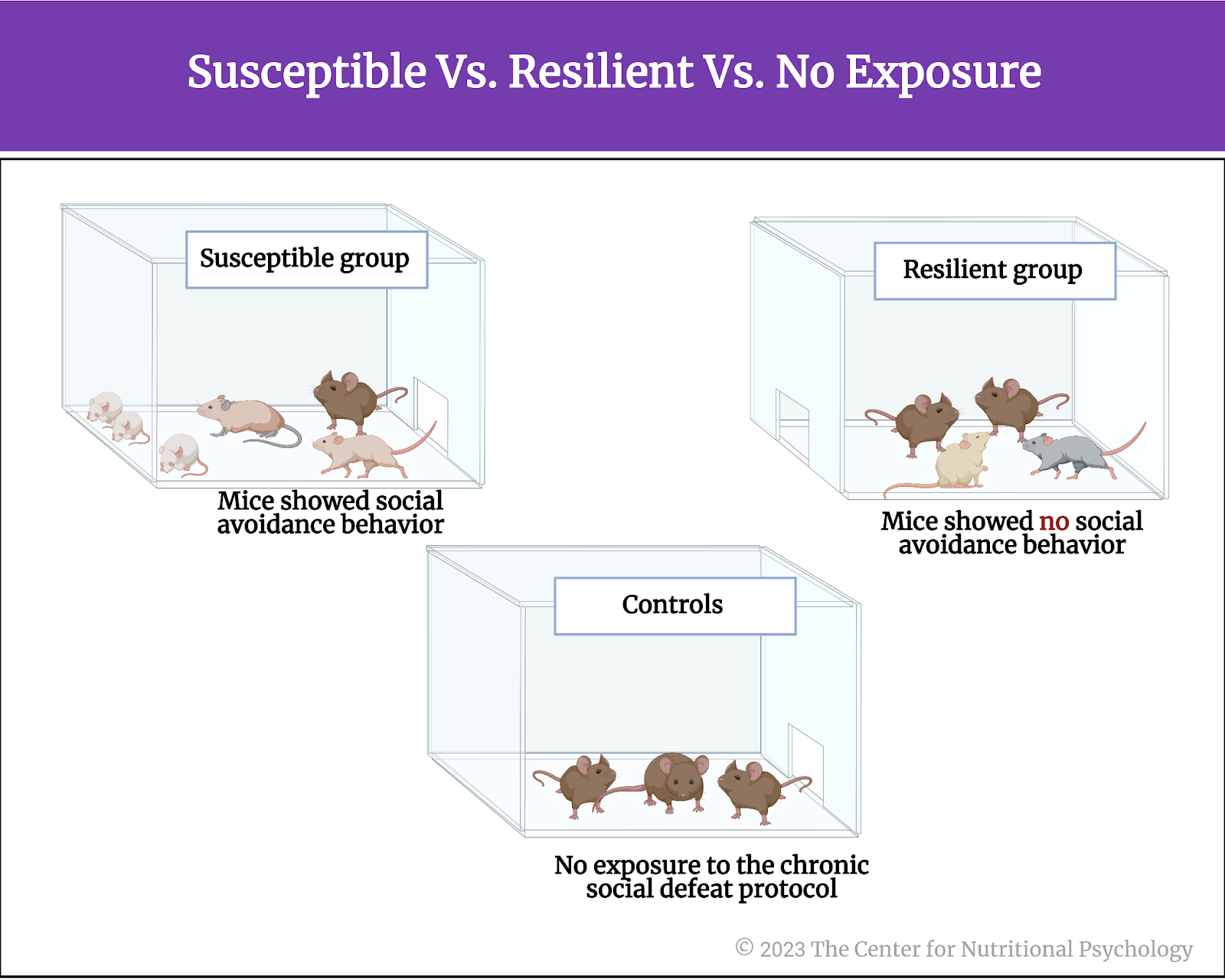

The study authors applied the chronic defeat stress protocol on a group of mice. Afterward, researchers examined the social behavior of these mice (towards other mice, using a social interaction test). They noticed that some of these mice started avoiding contact with other mice in a test situation, i.e., manifested social avoidance behavior, while others did not. They named the group of mice that showed social avoidance behavior the susceptible group. In contrast, the group of mice that did not show social avoidance behavior was named the resilient group. Researchers kept a third group of the same genetic strain of mice as controls and did not expose them to the chronic social defeat protocol (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Susceptible vs. resilient vs. no exposure

After the procedure, researchers collected stool samples from the mice and conducted their genetic analysis in order to identify the compositions of microorganisms present in the guts of these mice. This procedure is called the metagenomic sequencing of the gut microbiota. They also used a procedure called flow cytometry to determine the number and characteristics of gamma-delta T lymphocytes in the gut and in the meninges of these mice.

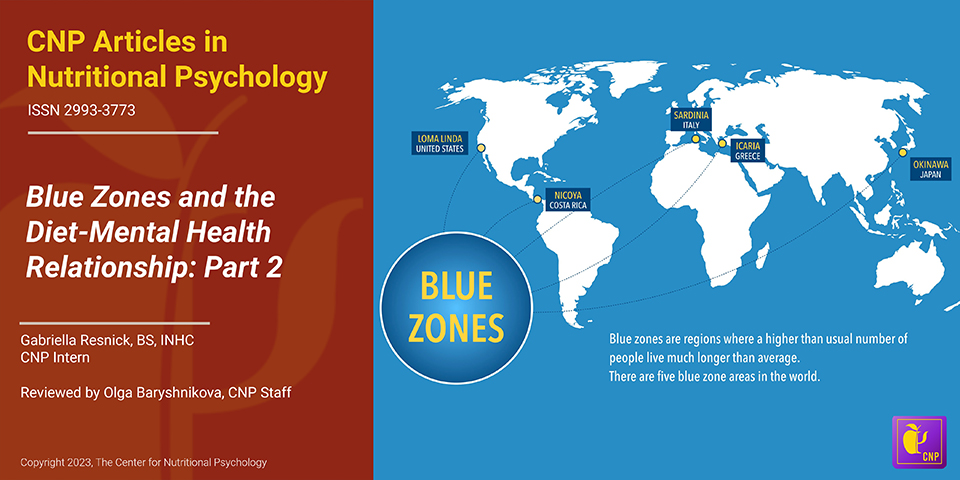

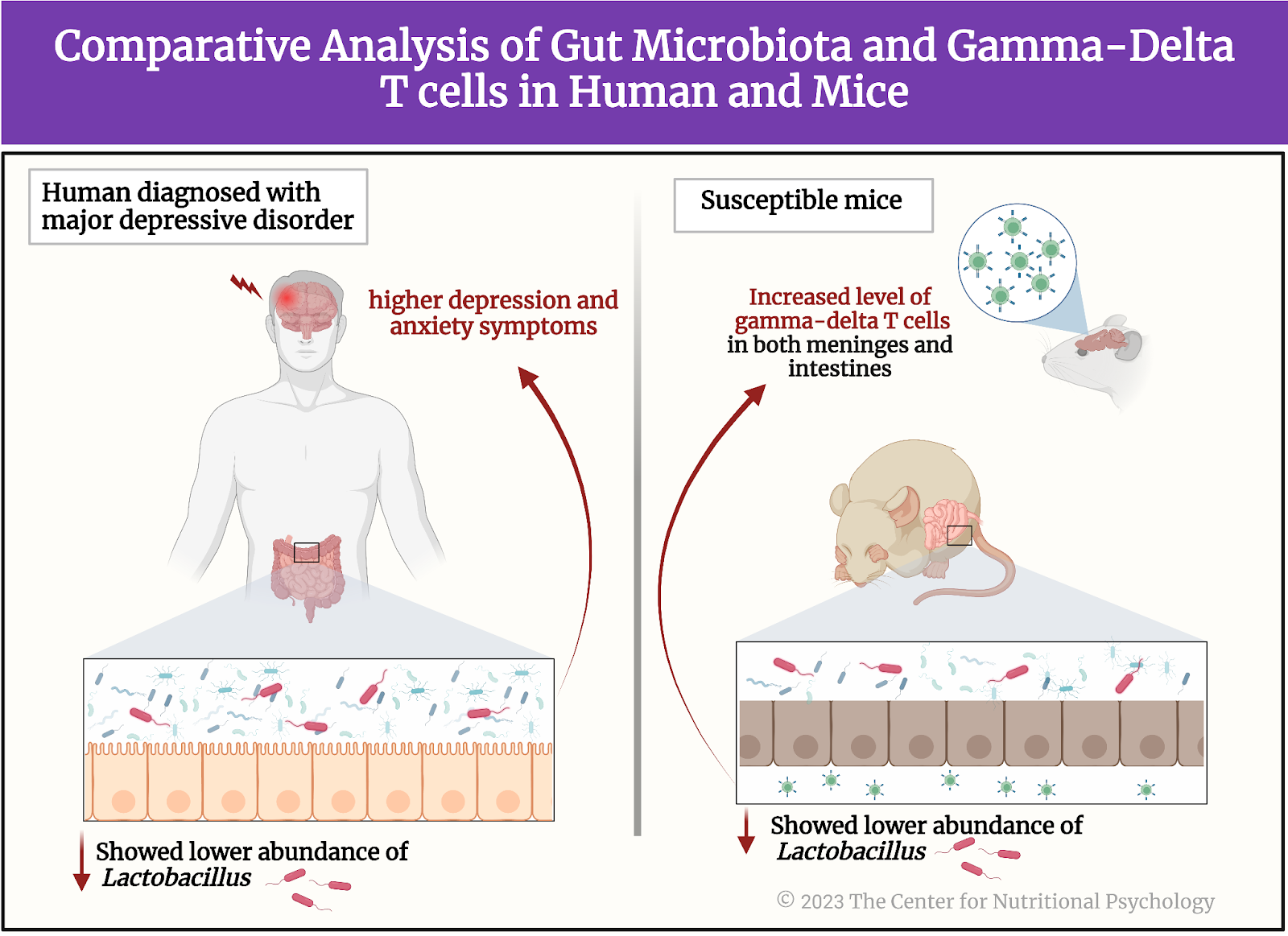

Comparison with humans

Parallel with this experiment, researchers investigated the differences in the composition of gut microbiota in humans diagnosed with major depressive disorder and healthy individuals by analyzing their stool samples. They found that a lower abundance of the Lactobacillus group of bacteria in the gut was associated with higher depression and anxiety symptoms. They confirmed this using three different assessments of depression and anxiety symptoms (the Montgomery-Asberg depression scale, the Hamilton Depression scale, and the Hamilton Anxiety Scale)(Zhu et al., 2023). Based on this, study authors assumed that concentrations of these bacteria in the gut might play a role in the vulnerability to stress in mice and humans. They decided to look for differences in the abundance of Lactobacillus bacteria in different groups of mice in their experiment.

Susceptible mice had a reduced abundance of Lactobacillus johnsonii bacteria in the gut! (See Figure 5).

Figure 5. Humans + Mouse experiment showing a lower abundance of lactobacillus in gut bacteria = with higher depression and anxiety

Figure 5. Humans + Mouse experiment showing a lower abundance of lactobacillus in gut bacteria = with higher depression and anxiety

A comparison of the gut microbiota of susceptible mice, resilient mice, and the control group showed that susceptible mice had less diverse microbial populations in the gut. The gut microbiota of susceptible mice differed from the gut microbiota of resilient mice and the control group on a number of bacterial species. As researchers expected, one of these species was Lactobacillus Johsonii. Their concentration was reduced in susceptible mice’s guts compared to resilient mice and the control group.

Susceptible mice had increased concentrations of gamma-delta T cells in both meninges and intestines

Given the previously described relationship between Lactobacillus bacteria and immune responses, researchers examined whether concentrations of gamma-delta T lymphocytes were increased in mice exposed to the chronic social defeat stress treatment. Results showed that susceptible mice had increased concentrations of gamma-delta T lymphocytes in their colons and meninges (membranes surrounding the brain) compared to resilient and healthy mice.

Susceptible mice had increased concentrations of gamma-delta T lymphocytes both in their colons and their meninges

In susceptible mice, many of the gamma-delta T cells in brain membranes came from the gut!

Researchers then wanted to know whether the gamma-delta T cells found in the meninges of susceptible mice were cells that differentiated there or those cells that traveled from the gut. They identified differences between these two types of gamma-delta T cells and measured their concentrations. Results showed that, in resilient mice and the control group, gamma-delta T lymphocytes found in the meninges were indeed differentiated. However, in susceptible mice, there were fewer such cells, but many gamma-delta T lymphocytes came from the gut.

In susceptible mice, there were fewer such cells, but there were lots of gamma-delta T lymphocytes that came from the gut

Social avoidance after the chronic social defeat stress does not develop in mice without gamma-delta T lymphocytes.

Finally, researchers wanted to test whether the gamma-delta T lymphocytes were responsible for the social avoidance behavior after exposure to chronic social defeat. They repeated the procedure on a new group of special mice that did not have the gamma-delta T cells. As researchers expected, these mice did not develop social avoidance behavior after exposure to the chronic social defeat stress protocol.

Conclusion

The study showed that a certain type of white blood cells – gamma-delta T lymphocytes and their accumulation play a key role in changes to behavior induced by stress. In the context of MGBA-DMHR, it also demonstrates interactions between gut microbiota, the body’s immune responses, and the brain when an organism is stressed. Given that many of the physiological processes in mice are similar to those in humans, these findings contribute to the scientific understanding of physiological mechanisms of behavioral changes that chronic stress and related disorders in humans. These insights can help develop novel ways to treat and prevent major depressive disorder and other stress-related disorders. They can also open new approaches to diagnosing individual susceptibility to stress and increasing resilience.

The paper “Dectin-1 signaling on colonic gamma-delta T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses” was authored by Xiaolei Zhu, Shinji Sakamoto, Chiharu Ishii, Matthew D. Smith, Koki Ito, Mizuho Obayashi, Lisa Unger, Yuto Hasegawa, Shunya Kurokawa, Taishiro Kishimoto, Hui Li, Shinya Hatano, Tza-Huei Wang, Yasunobu Yoshikai, Shin-ichi Kano, Shinji Fukuda, Kenji Sanada, Peter A. Calabresi, and Atsushi Kamiya.

For more research in the Microbiota Gut-Brain Axis — Diet-Mental Health Relationship (MGBA-DMHR), visit CNP’s Nutritional Psychology Research Library (NPRL) Microbiota Gut-Brain Axis—Diet-Mental Health Relationship research category, or enroll in NP 120: Microbiota Gut-Brain Axis and the DMHR (available in May 2023).

References

Armon, G., Melamed, S., Toker, S., Berliner, S., & Shapira, I. (2014). Joint Effect of Chronic Medical Illness and Burnout on Depressive Symptoms Among Employed Adults. Health Psychology, 33(3), 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033712

Golden, S. A., Covington, H. E., Berton, O., & Russo, S. J. (2011). A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nature Protocols, 6(8), 1183–1191. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2011.361

Goodman, L., Saxe, L., & Harvey, M. (1991). Homelessness as psychological trauma. American Psychologist, 46(11), 1219.

Hodes, G. E., Pfau, M. L., Leboeuf, M., Golden, S. A., Christoffel, D. J., Bregman, D., Rebusi, N., Heshmati, M., Aleyasin, H., Warren, B. L., Lebonté, B., Horn, S., Lapidus, K. A., Stelzhammer, V., Wong, E. H. F., Bahn, S., Krishnan, V., Bolaños-Guzman, C. A., Murrough, J. W., … Russo, S. J. (2014). Individual differences in the peripheral immune system promote resilience versus susceptibility to social stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(45), 16136–16141. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1415191111

Tsukerman, D., Leger, K. A., & Charles, S. T. (2020). Work-family spillover stress predicts health outcomes across two decades. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113516

Zhao, Y., Niu, C., & Cui, J. (2018). Gamma-delta (γδ) T Cells: Friend or Foe in Cancer Development. Journal of Translational Medicine, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1378-2

Zhu, X., Sakamoto, S., Ishii, C., Smith, M. D., Ito, K., Obayashi, M., Unger, L., Hasegawa, Y., Kurokawa, S., Kishimoto, T., Li, H., Hatano, S., Wang, T. H., Yoshikai, Y., Kano, S. ichi, Fukuda, S., Sanada, K., Calabresi, P. A., & Kamiya, A. (2023). Dectin-1 signaling on colonic γδ T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses. Nature Immunology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01447-8