- Patients struggling with food intake regulation often report obsessively thinking about food for prolonged periods and spending lots of time doing things related to food.

- A study published in Nutrients proposes that this phenomenon of heightened reactivity to food cues be termed “food noise.”

- It proposes a conceptual model describing factors linking food cues and consequences of heightened food cue reactivity, including ways to regulate it.

Traditionally, people widely believed that individuals gain weight simply because they are not careful and eat too much. Religious teachings, for example, speak about gluttony, one of the deadly sins symbolizing primarily excessive or overindulgent eating. In this view, people become overweight more or less because their willpower is not strong enough to avoid the temptation to overeat. Similarly, to lose weight, they need to “tough it out” and show sufficient willpower to resist the urge to overeat.

In this view, people become overweight more or less because their willpower is not strong enough to avoid the temptation to overeat. They need to “tough it out” and show sufficient willpower to resist the urge to overeat

However, we are all aware of people who fail to lose weight or maintain healthy body weight in spite of significant efforts. Others maintain a healthy physique without paying much attention to their diets.

Given these observations, can being overweight or maintaining a healthy weight really be just a matter of willpower? Scientific discoveries made in recent decades say otherwise.

Can being overweight or maintaining a healthy weight really just be just a matter of willpower?

What causes obesity?

The obvious answer is that obesity results from consuming more calories than one expends. However, things are far from being so simple. For instance, our food intake is guided by processes in our brain that tell us when we need to eat and when to stop eating. This is the case in humans and most other complex species (Wilding, 2001).

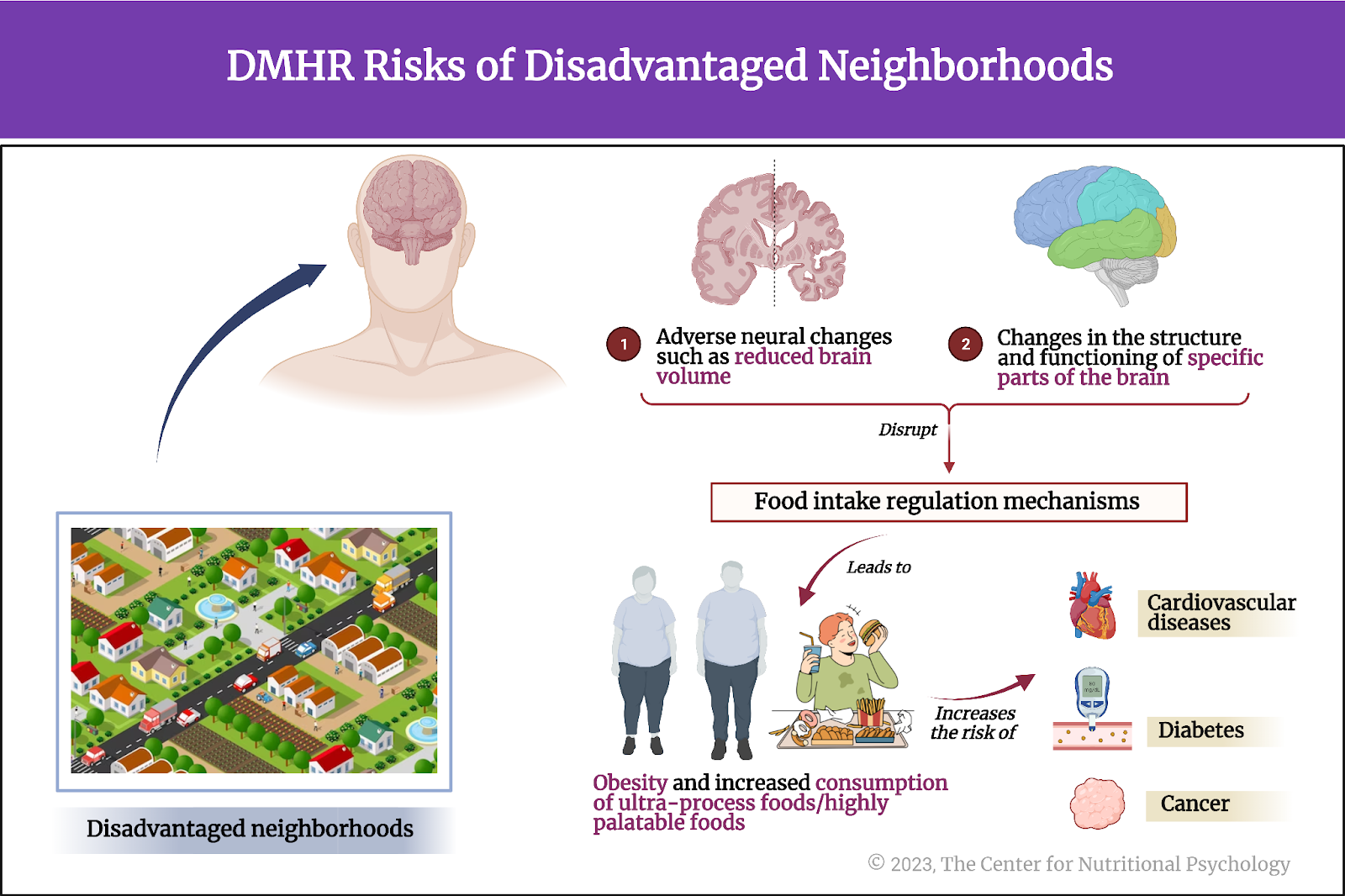

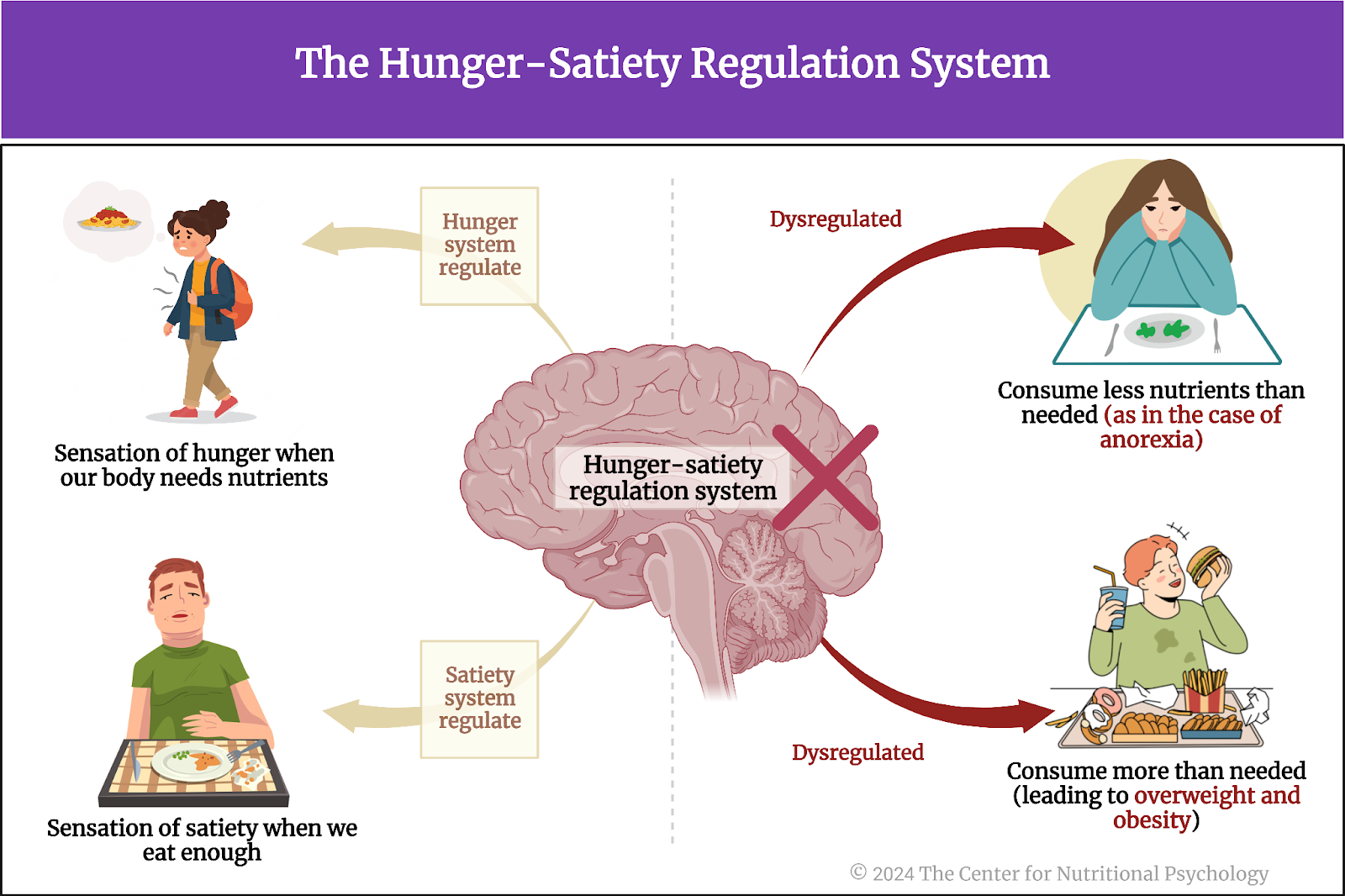

The mechanism of hunger creates a sensation of hunger when our body needs nutrients and a sensation of satiety when we eat enough. These sensations make us start or stop eating. However, studies show that this hunger-satiety regulation system is dysregulated in many individuals. This dysregulation can give rise to dysfunctional eating behaviors. When this happens, individuals may either consume less nutrients than they need, as observed in the case of anorexia, or more than their body needs, contributing to overweight and obesity (Pujol et al., 2021) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Hunger-Satiety Regulation System

The food intake regulation system

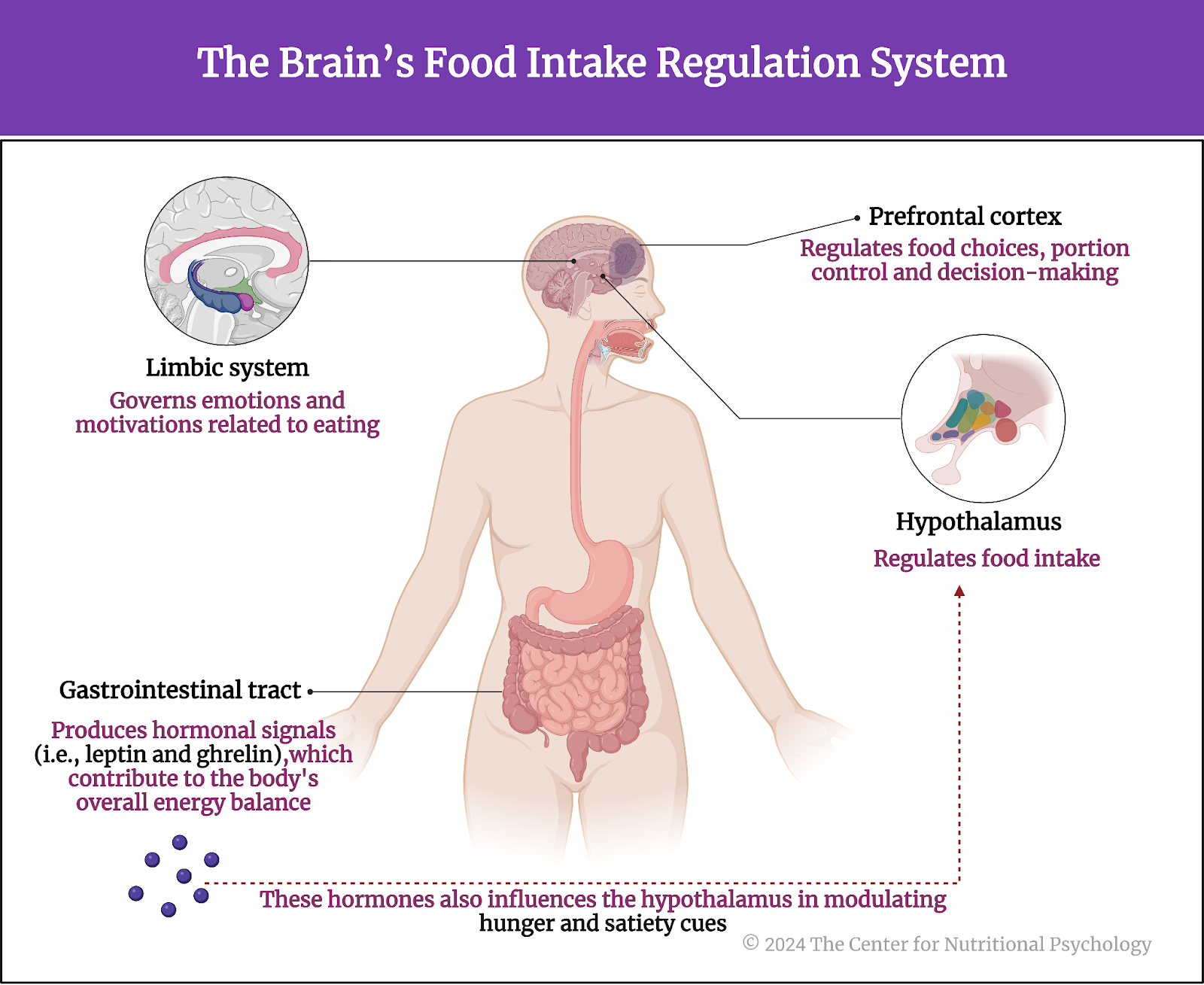

The brain’s hypothalamus region regulates food intake through a complex system of neural circuits. However, this neural network in the hypothalamus interacts with many other systems of the body, such as the limbic system, which governs emotions and motivations related to eating. Higher cognitive processes, mediated by regions like the prefrontal cortex, play a crucial role in food choices and portion control decision-making. Furthermore, hormonal signals from the gastrointestinal tract, such as leptin and ghrelin, contribute to the body’s overall energy balance and influence the hypothalamus in modulating hunger and satiety cues. This intricate interplay among neural circuits, emotional centers, cognitive functions, and hormonal systems collectively orchestrates the complex regulation of food intake (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The brain’s food intake regulation system

As with any highly complex system, many things can lead to the dysregulation of the food intake control system. Studies show that genetic factors, such as those leading to the deficit of leptin, the hormone responsible for inhibiting feelings of hunger, can dysregulate this system and lead to obesity. Similar effects were observed in individuals with damage to the hypothalamus regions of the brain (Wilding, 2001).

The strong increase in the share of obese individuals throughout the world in recent decades, the obesity pandemic, has pointed to additional factors leading to the dysregulation of the food intake control system. Studies find that diets based on certain types of food, such as highly processed foods or foods high in fat and sugars, dysregulate food intake, leading to obesity (Hedrih, 2023). Experiments show that feeding mice high-fat diets disrupts their food intake regulation and makes them develop obesity (Ikemoto et al., 1996), but also changes certain structures in the brains of their offspring (Lippert et al., 2020).

Diets based on highly processed foods or foods high in fat and sugars disrupt the regulation of food intake, consequently contributing to the development of obesity

Finally, research suggests that human food consumption is influenced not solely by a deficiency of nutrients in the body but frequently by learned food cues from childhood and throughout life (Hedrih, 2023a; Schulte et al., 2019). These are the associations between our perceptions of food items and our experiences (taste, smell, etc.) of them. New studies indicate that people might differ in how reactive they are to these food queues, with some people being very much overwhelmed by them. This led researchers to coin the term “food noise” to describe this situation (Hayashi et al., 2023).

Humans consume food often in response to food cues learned in childhood and throughout life

What is ‘food noise’?

Our brains excel at triggering motivational responses when exposed to food cues (a concept involved with the term “availability” within nutritional psychology) (Morphew-Lu et al., 2021). Simply put, our brains are very good at making us desire the foods and beverages we see, smell, hear, or sense in another way (Hayashi et al., 2023). For example, when we smell the aroma of freshly baked pastries, hear the sizzle of bacon in a skillet, or see desserts at a party or in a grocery store, we often develop a desire to consume that food. This responsiveness to food cues constitutes our reactivity to them.

New studies indicate that people might differ in how reactive they are to food cues, with some people being very much overwhelmed by them

From an evolutionary perspective, being reactive to food cues has contributed to the survival of humans in times of food scarcity. It made them use opportunities to meet their nutritional needs whenever they arose, regardless of whether their body needed those nutrients at that very moment or not. However, in modern industrial societies, highly palatable and energy-dense foods are widely available, and the environment tends to be full of food cues. These include foods exposed for sale in grocery stores, food supplies kept at home, and many food advertisements found across various media channels.

People vary in their responsiveness to food cues. While some individuals can easily overlook the numerous food cues they encounter, others exhibit heightened reactivity. The latter group can be described as experiencing ‘food noise.’

People vary in their responsiveness to food cues

The authors of this paper, Daisuke Hayashi and his colleagues, define food noise as “heightened and/or persistent manifestations of food cue reactivity, often leading to food-related intrusive thoughts and maladaptive eating behaviors.” Individuals experiencing food noise find themselves constantly thinking about food, checking food ordering websites, and being obsessively preoccupied with food. This then easily leads them to act on these thoughts, resulting in overeating, binge eating, and weight gain as a consequence.

Food noise is defined as “heightened and/or persistent manifestations of food cue reactivity, often leading to food-related intrusive thoughts and maladaptive eating behaviors”

How was food noise discovered?

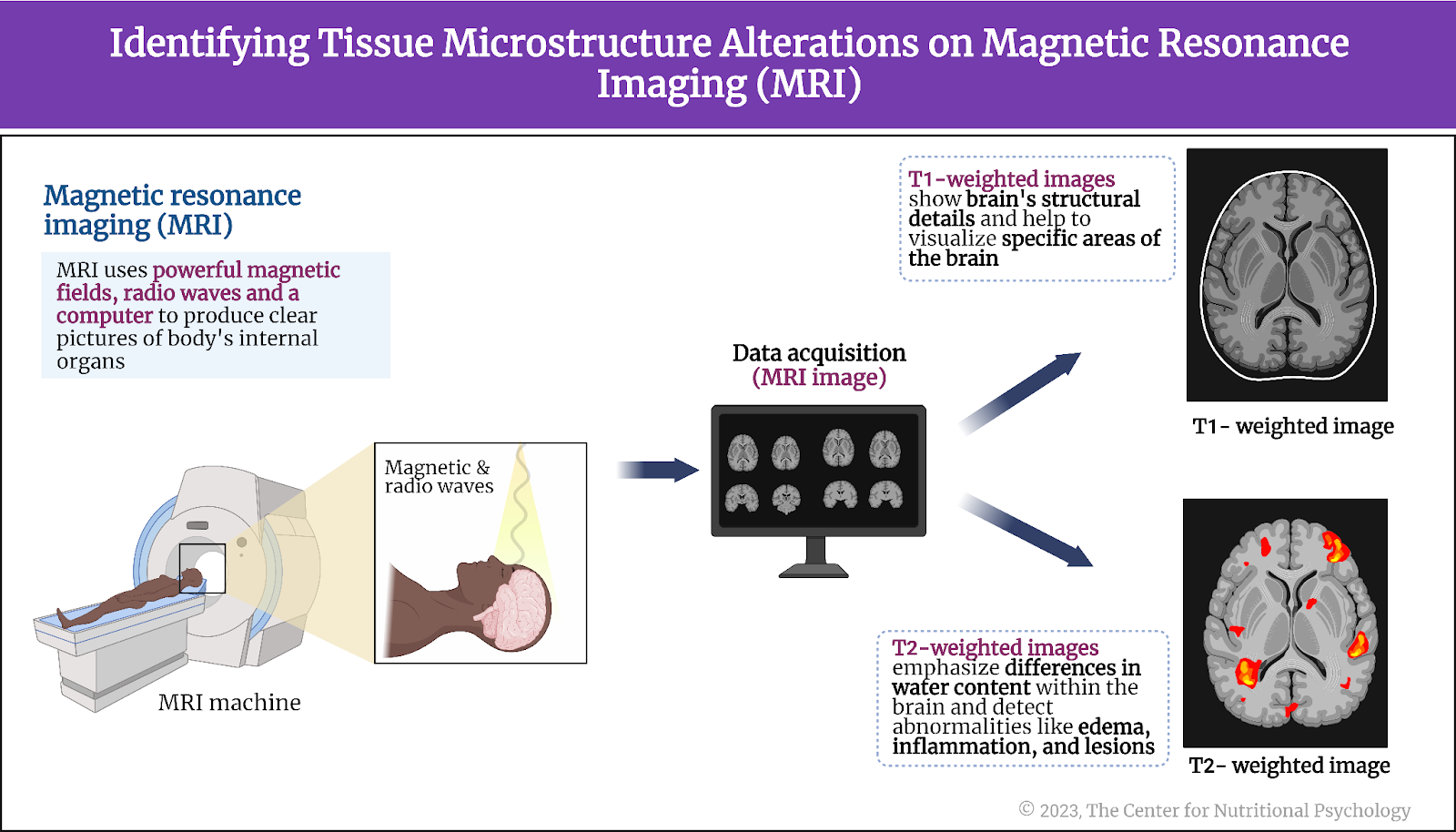

In recent decades, the global population has witnessed a significant increase in the prevalence of overweight and obese individuals (Wong et al., 2022). This obesity epidemic has coincided with a surge in the number of people affected by type 2 diabetes, a chronic condition characterized by ineffective cell responses to insulin (the hormone that facilitates glucose uptake into cells of the body). This inefficiency leads to impaired glucose absorption and elevated blood sugar levels. Health professionals widely prescribe a type of medicine called GLP-1Ras or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists to treat type 2 diabetes. GLP-1RAs mimic the action of the glucagon-like peptide-1 hormone, helping to lower blood sugar levels. They do this by increasing insulin production and reducing glucagon secretion, a hormone that raises blood sugar levels, through several other mechanisms (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. GLP-1Ras mechanism

Very soon after the use of GLP-1Ras became widespread medical practitioners noted that these medicines often also promote weight loss. Scientists identified multiple physiological mechanisms through which this effect can be achieved. However, many practitioners noted that patients using GLP-1Ras sometimes report that the “food noise” in their heads has decreased after using them. They reported that they stopped constantly thinking about foods or the next meal they planned to consume. Generally, the amount of thinking about food or food cue reactivity has been reduced (Hayashi et al., 2023).

The Cue–Influencer–Reactivity–Outcome (CIRO) model of food cue reactivity

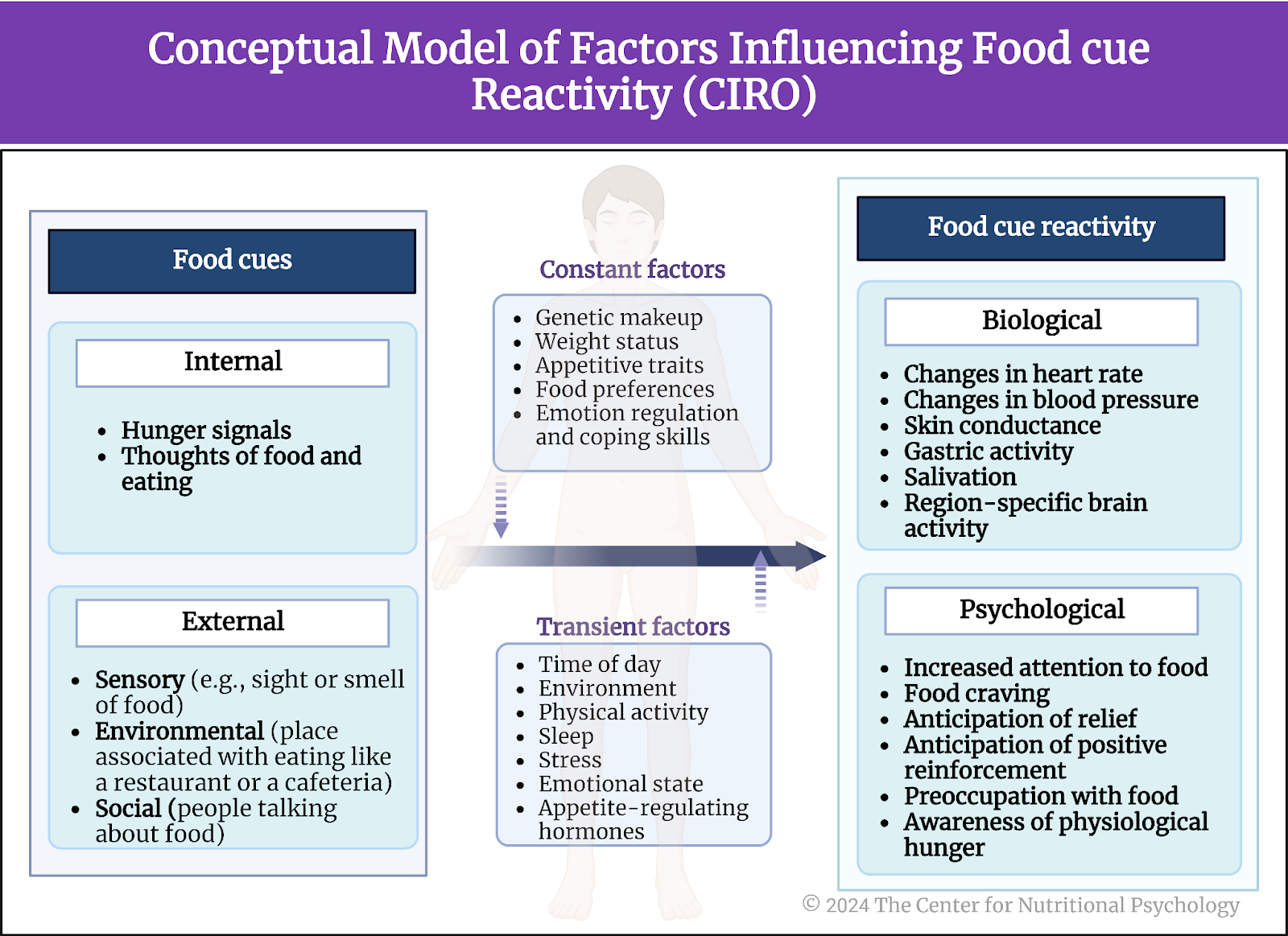

Based on these and various other findings, Daisuke Hayashi and his colleagues proposed a conceptual model of factors influencing food cue reactivity. They called this model CIRO, which is short for the Cue–Influencer–Reactivity–Outcome. This model proposes that food cues can be internal, like hunger signals coming from the body or thoughts of food and eating, or external, like sensory cues (e.g., sight or smell of food), environmental (e.g., being in a place associated with eating like a restaurant or a cafeteria), or social (e.g., other people talking about food) (more about the Diet Sensory-Perceptual Relationship and the Diet-Interoceptive Relationship can be found in NP 110: Introduction to Nutritional Psychology Methods) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Conceptual model of factors influencing food cue reactivity (Adapted from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224809)

The presence of these food cues elicits different degrees of food cue reactivity. These degrees depend on various factors that modify food cue reactivity. Some of these factors are constant. These include the genetic makeup of the individual, weight status, appetitive traits, food preferences, and emotion regulation and coping skills. Others are transient. These include the time of day (e.g., a person will likely be more reactive to food cues at a time he/she usually eats), the environment, physical activity, sleep (lack of sleep tends to make one more prone to eat), stress, emotional state, or appetite-regulating hormones (e.g., level of leptin, ghrelin and other hormones in circulation in the body).

The presence of these food cues elicits different degrees of food cue reactivity

Depending on the combination of present food cues and these modifying factors, the body will react more or less strongly (or not at all) to these cues. The manifestations of this reactivity can be biological or psychological. Biological manifestations include changes in heart rate, blood pressure, skin conductance, gastric activity, salivation, or region-specific brain activity. Psychological manifestations include increased attention to food (attention bias), food craving, anticipation of relief (if food is eaten), anticipation of positive reinforcement, preoccupation with food, and awareness of physiological hunger (the feeling of hunger).

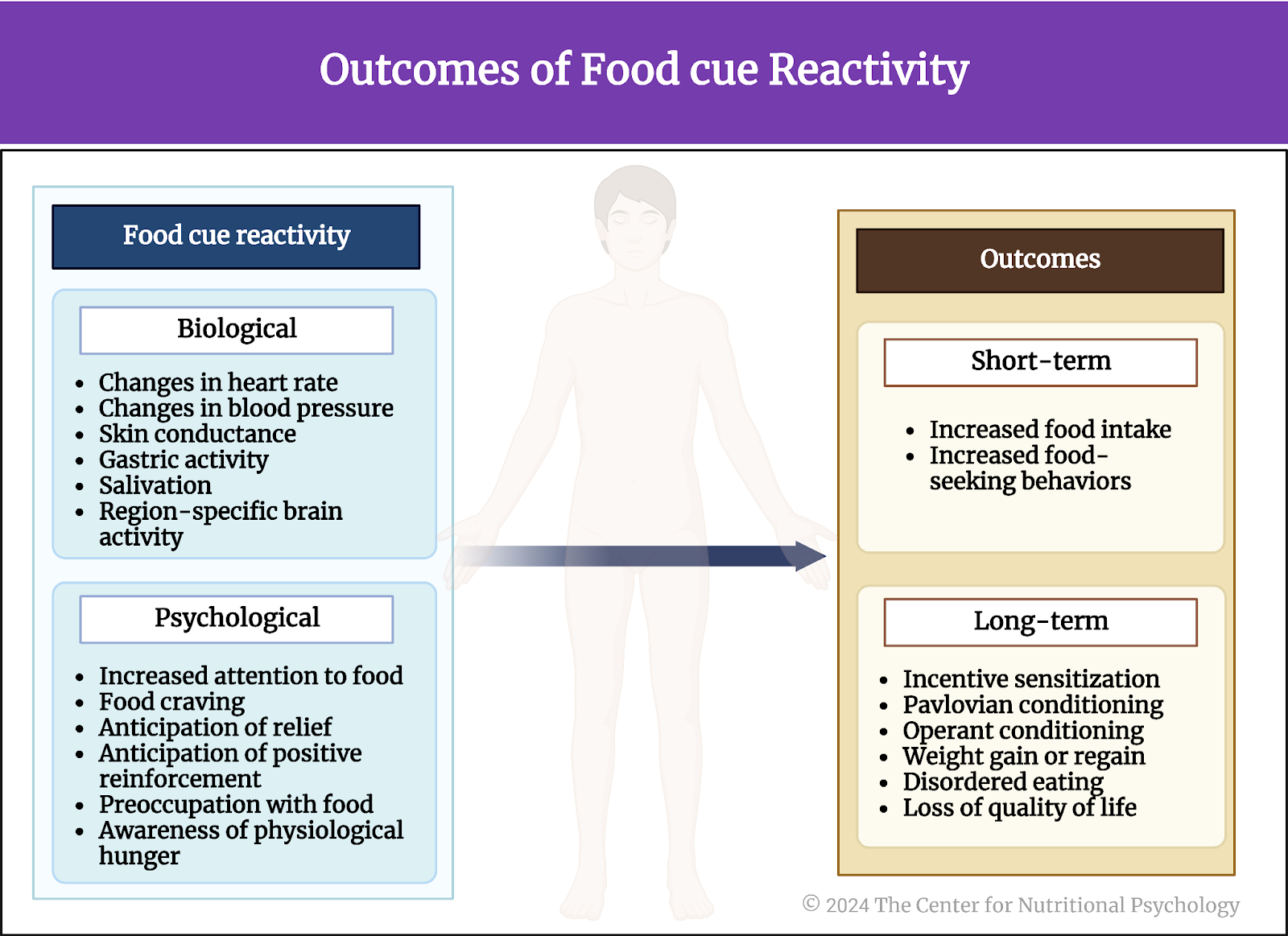

Food cue reactivity consequently leads to a series of outcomes, some of which are short-term, while others are long-term. Short-term outcomes of heightened food reactivity include increased food intake and food-seeking behaviors. Long-term outcomes represent the results of repeated instances of exposure to food cues accompanied by heightened food cue reactivity (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Food cue reactivity outcomes (Adapted from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224809)

This involves long-term behavioral outcomes that appear over longer periods. For example, it includes making food cues more powerful in encouraging overeating, a phenomenon known as ‘incentive sensitization’ (being extra sensitive to rewards). It also involves the direct connection between food cues and food intake, referred to as ‘Pavlovian conditioning’ (similar to how we associate a bell ringing with mealtime).

Moreover, food-seeking behaviors may intensify due to the rewarding nature of highly palatable foods, a process called ‘operant conditioning’ (like training ourselves to want certain things). Over time, heightened reactivity to food cues in environments with abundant food can lead to weight gain or regain, disordered eating, and a decline in overall quality of life, as illustrated in Figure 5 above.

Food-seeking behaviors can also become more pronounced due to the rewarding nature of highly palatable foods (operant conditioning)

Conclusion

This conceptual paper proposes the concept of “food noise,” defined as heightened and/or persistent manifestations of reactivity to food cues, often leading to food-related intrusive thoughts and maladaptive eating behaviors. In modern societies, where food abundance is prevalent , heightened food reactivity, i.e., food noise, may induce both biological and psychological changes that contribute to weight gain, disordered eating, and obesity.

Food noise may induce both biological and psychological changes that contribute to weight gain, disordered eating, and obesity

The paper’s authors also proposed a theoretical CIRO model of food cue reactivity that identifies factors that modify food cue reactivity. Controlling these factors can reduce food noise and thus help individuals maintain a healthy and balanced diet and a healthy weight. Most notably, the model proposes that food noise can be reduced by modifying the environment to reduce people’s exposure to food cues and influencing the transient factors that modify food cue reactivity.

The review paper “What Is Food Noise? A Conceptual Model of Food Cue Reactivity” was authored by Daisuke Hayashi, Caitlyn Edwards, Jennifer A. Emond, Diane Gilbert-Diamond, Melissa Butt, Andrea Rigby, and Travis D. Masterson.

More about dietary intake behaviors and neural mechanisms can be found in online courses through CNP entitled NP 110: Introduction to Nutritional Psychology Methods, NP 120 Part I: Microbes in our Gut: An Evolutionary Journey into the World of the Microbiota Gut-Brain Axis and the DMHR, and NP 120 Part II: Gut-Brain Diet-Mental Health Connection: Exploring the Role of Microbiota from Neurodevelopment to Neurodegeneration.

References

Hayashi, D., Edwards, C., Emond, J. A., Gilbert-Diamond, D., Butt, M., Rigby, A., & Masterson, T. D. (2023). What Is Food Noise? A Conceptual Model of Food Cue Reactivity. In Nutrients (Vol. 15, Issue 22). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224809

Hedrih, V. (2023a). Are Hunger Cues Learned in Childhood? CNP Articles. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/are-hunger-cues-learned-in-childhood/

Hedrih, V. (2023b). Scientists Propose that Ultra-Processed Foods be Classified as Addictive Substances. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/scientists-propose-that-ultra-processed-foods-be-classified-as-addictive-substances/

Ikemoto, S., Takahashi, M., Tsunoda, N., Maruyama, K., Itakura, H., & Ezaki, O. (1996). High-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and obesity in mice: Differential effects of dietary oils. Metabolism, 45(12), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90185-7

Lippert, R. N., Hess, S., Klemm, P., Burgeno, L. M., Jahans-Price T, Walton, M. E., Kloppenburg, P., & Brüning, J. C. (2020). Maternal high-fat diet during lactation reprograms the dopaminergic circuitry in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 130(7), 3761–3776.

Morphew-Lu, E., Lokken, K., Doswell, C., Protogerous, C., Greunke, S. (2021). Module 3: The Diet-Behavior Relationship. In E. Lu (Ed.), NP 110: Introduction to Nutritional Psychology. The Center for Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/np110/

Pujol, J., Blanco-Hinojo, L., Martínez-Vilavella, G., Deus, J., Pérez-Sola, V., & Sunyer, J. (2021). Dysfunctional Brain Reward System in Child Obesity. Cerebral Cortex, 31, 4376–4385. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab092

Schulte, E. M., Yokum, S., Jahn, A., & Gearhardt, A. N. (2019). Food Cue Reactivity in Food Addiction: a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study HHS Public Access. Physiol Behav, 208, 112574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112574

Wilding, J. P. H. (2001). Causes of obesity. Practical Diabetes International, 18(8), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/PDI.277

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005