Gatorade, Muscle Milk, Protein Powders, and Carb-Loading — all things elite athletes know well. Nutrition is not a new topic as it relates to sports performance. It’s no secret to athletes, coaches, and trainers that diet impacts an athlete’s physical health and their ability to physically train, perform, and recover. But what is a newer, more novel concept is how diet can impact an athlete’s mental health and their ability to perform.

The field of Sport Psychology has been helping athletes to develop psychological skills that allow them to unlock their potential for years. Sport Psychology can be defined as “the scientific study of the psychological factors that are associated with participation and performance in sport, exercise, and other types of physical activity.” (APA, 2021). Professionals in this field are trained in techniques such as mindfulness, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and counseling to empower athletes to develop the focus, confidence, and motivation they need to perform optimally in their sport. Only now are we beginning to establish the evidence base showing how diet can influence the mental performance of athletes.

Improving an athlete’s mindset through mental training can help improve their athletic performance.

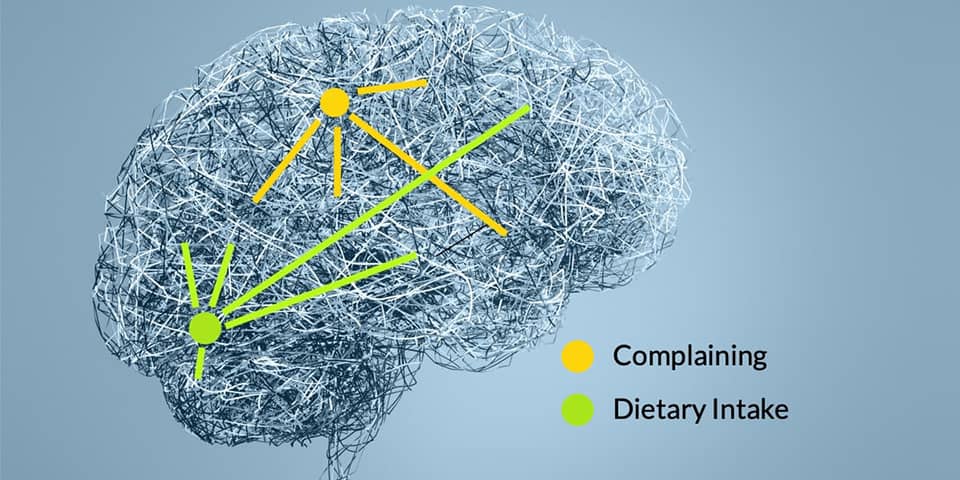

It has well been established that improving an athlete’s mindset through mental training can help improve their athletic performance. Research is now showing that a person’s diet plays a strong role in the cognitive processes that are important to peak performance, including maintaining focus (Baker et al., 2014), learning and remembering (Hepsomali et al., 2021), controlling emotions (Dorthy, 2019), and even handling pressure in high-stress situations. In fact, one study found that adding probiotics in the form of yogurt to an elite diver’s diet actually decreased the risk of “choking” under the pressure of competition (Dong et al., 2020). Choking is a phenomenon that occurs often in sports, one that Mental Performance Coaches and Sport Psychologists work with athletes to regulate, and a circumstance that we now know can be improved through dietary changes.

In sport, athletes face intense physical and cognitive demands.

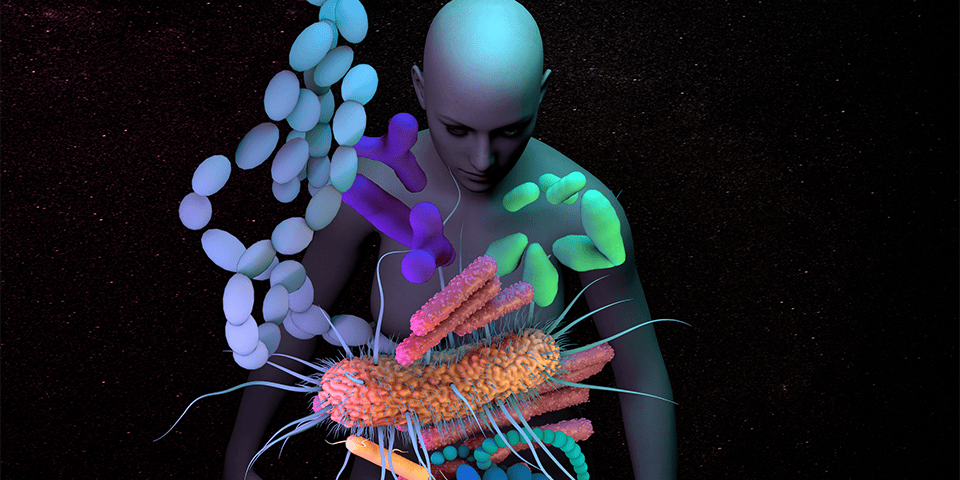

In sport, athletes face intense physical and cognitive demands. These demands require unique nutritional needs to support optimal athletic performance, as well as physical and mental health. Current dietary guidelines for athletes take their physical performance into consideration but fail to account for how dietary habits may impact one’s overall physical and mental well-being. For example, it has been shown that endurance athletes may be at higher risk for intestinal permeability (Mach & Fuster-Botella, 2017). Intestinal lining permeability has recently been implicated in several mental disorders and cognitive processes (Mohajeri et al., 2018).

The Diet and Sport Psychology research category has been created in CNP’s Nutritional Psychology Research Library (NPRL).

The Diet and Sport Psychology research category has been created in CNP’s Nutritional Psychology Research Library (NPRL) to bring awareness of current research to coaches, trainers, athletes, and sport psychologists regarding the connection between athletic performance and nutrition. This research category is contributing to the field of Sport Psychology by making the connection between an athlete’s diet and their ability to perform psychologically, cognitively, and behaviorally.

References

Baker, L. B., Nuccio, R. P., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2014). Acute effects of dietary constituents on motor skill and cognitive performance in athletes. Nutrition Reviews, 72(12), 790–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/nure.12157

Clark, A., Mach, N. Exercise-induced stress behavior, gut-microbiota-brain axis and diet: A systematic review for athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr, 13, 43 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-016-0155-6

Defining the practice of Sport and … – APA divisions. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2021, from https://www.apadivisions.org/division-47/about/resources/defining.pdf.

Dong, W., Wang, Y., Liao, S., Lai, M., Peng, L., & Song, G. (2020). Reduction in the Choking Phenomenon in Elite Diving Athletes Through Changes in Gut Microbiota Induced by Yogurt Containing Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Microorganisms, 8(4), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8040597

Du, Dorothy. (2019). You may be what you eat, can you be violent due to your food?. European Journal of Biomedical and Phramaceutical Sciences, 6(7), 20-28.

Hepsomali P, Greyling A, Scholey A and Vauzour D (2021) Acute Effects of Polyphenols on Human Attentional Processes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 678769. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2021.678769

Mach, N., Fuster-Botella, D. (2017). Endurance exercise and gut microbiota: A review. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6 (2), 179-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.05.001

Mohajeri, M. H., La Fata, G., Steinert, R. E., & Weber, P. (2018). Relationship between the gut microbiome and brain function. Nutrition Reviews, 76(7), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuy009