For hundreds of years, scientists have suspected a connection between our personality traits and taste preferences. Anton Brillat-Savarin, the famous French gastronome, is quoted saying, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.”

Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.

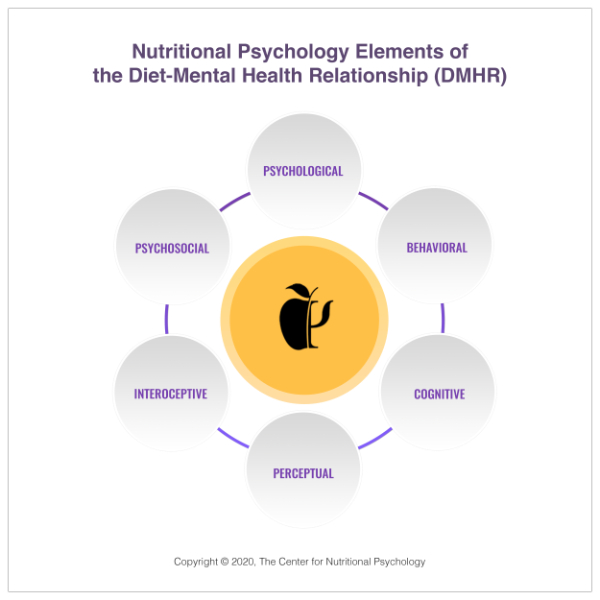

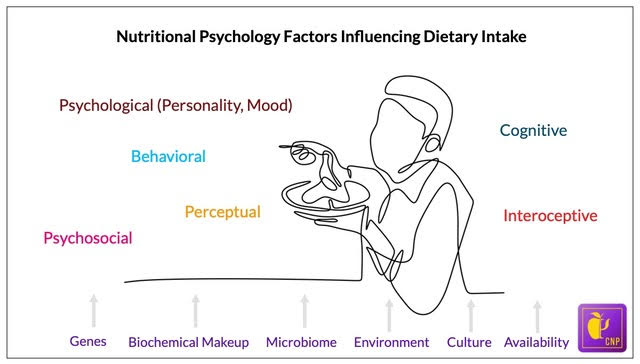

But what influences what we eat? It turns out that a symphony of elements influences our dietary intake patterns. These elements include (but are not limited to) our psychological traits (and mood states), cognitive and perceptual processes, behavioral attributes, psychosocial (including cultural) environment, and interoceptive experience. Each of these elements, in turn, is driven by physiological, biological, neuropsychological, and environmental states that are constantly at play within us (figure 1) (see the Nutritional Psychology Research Library).

Figure 1. Elements of the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR) informing nutritional psychology (NP)

Understanding the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR) involves a wealth of conceptual complexity. The burgeoning field of nutritional psychology is attempting to integrate this conceptual complexity into a singular infrastructure by which the conceptualization of the DMHR can grow (figure 1). Nutritional psychology involves understanding the myriad factors interconnecting our dietary intake with our psychological processes, functioning, and experience. A plethora of research exists (and is growing) to improve our understanding of these interconnections and is contained in the CNP Research Libraries.

What is Guiding What We Eat?

On the surface, many of us believe that what we eat is guided by what we like and want to eat (or in the current dietary intake landscape additionally, what we crave to eat and what is available to eat). In fact, what we eat goes far deeper than simply wanting and liking certain foods. A host of involuntary factors, of which we are mostly unaware, influence our daily dietary intake including our perceptions and preferences, personality, mood, behavioral attributes, and even genetics (Neuroscientist News, 2022). Let’s begin by looking at taste perception, preference, and their connection with personality traits.

Genetic Basis for Taste Perception and its Connection with Personality Traits

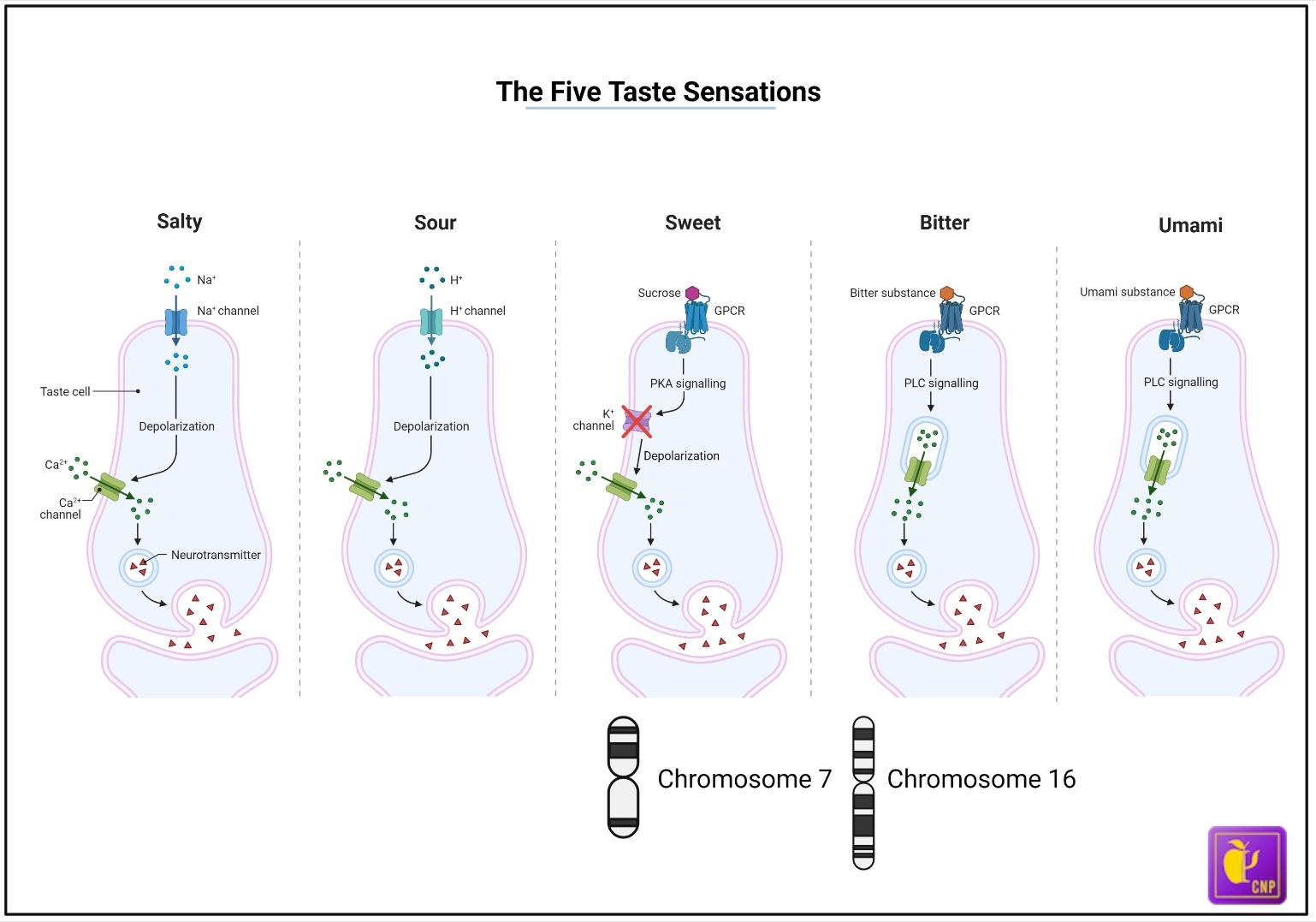

Perceiving taste involves complex pathways that interface with multiple cranial nerves and areas in our brain. The five taste sensations (bitter, sweet, umami, sour, and salt) arise because of the activation of specific taste receptor cells on the lingual papillae on the tongue. Specific genes encode the different taste receptors. Varieties in these genes lead to the expression of different proteins associated with different tasting abilities, preferences, and personality traits. This serves as the genetic basis for taste and the perception of taste.

Interestingly, sensory science divides people into supertasters, medium-tasters, and non-tasters. The TAS2R38 gene, located on chromosome 7, provides the genetic basis for taster status (Figure 2).

Supertasters are defined as individuals with uncommonly low gustatory thresholds and strong responses to moderate concentrations of taste stimuli (Supertaster – APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.). Supertasters have an unusually high number of taste buds. This gene in supertasters increases their perception of bitter flavors in foods.

Varieties in genes lead to the expression of different proteins associated with different tasting abilities, preferences, and personality traits.

For example, supertasters tend to find the taste of coffee to be very bitter. In relation to personality characteristics, studies have found that supertasters and medium-tasters tend to be more tense, apprehensive, and imaginative than non-tasters, while non-tasters are inclined to be more relaxed, placid, and practical (Mascie-Taylor et al., 1983).

Science also reveals a genetic basis for sweet liking, identified by a locus on chromosome 16 (Figure 2). Researchers divide the population into three categories related to the liking for sweetness: sweet-likers, sweet-neutral, and sweet dislikers. Regarding differences in the preferences for sweetness, studies have shown that these differences predicted intentions, prosocial personalities, and behaviors (Meier et al., 2012).

Figure 2. The five taste sensations. The genetic basis for sweet liking is identified by chromosome 16, while chromosome 7 provides the genetic basis for taster status

It is important to note that in addition to our genes, our biochemical makeup also plays a role in our food perception and preference. For example, one study showed that salivary testosterone levels correlated with the amount of spice (Tabasco in this case) that participants chose to add to their food (Bègue et al., 2015).

Now that we’re aware of the genetic (and biochemical) basis for taste perception and preference, and learned how our genes can influence personality, let’s look at how personality can influence food preference.

Personality and Food Preference

Regarding food preferences, key factors of a person’s personality, including openness to experience (i.e., curiosity vs. caution), have been found to correlate with various aspects of food preference. For example, in a study by Conner et al. (2017), people with personality attributes like openness scored above average on preference for new food experiences. The controversy associated with such research, however, is that it has largely been conducted using self-rated food preferences, not in settings with actual food choices.

Key factors of a person’s personality have been found to correlate with aspects of food preference.

Many studies have addressed this issue. For example, a 2016 study analyzed participants’ willingness to try new foods. In this study, bite-sized pieces of twelve food items were placed in front of each participant (these included: octopus, hearts of palm, seaweed, soya bean milk, blood sausage, Chinese sweet rice cake, pickled watermelon rind, raw fish, quail egg, star fruit, sheep milk cheese, and black beans). Findings showed that the most anxious participants were the least willing to try new foods (Otis, 2016). This has been supported by other publications showing that anxious patients exhibit greater food aversions (Spence, 2021).

The most anxious participants were the least willing to try new foods.

Taste Perception and its Influence on Mood and Behavior

Now that we’ve explored some interconnections between genes, taste perception, and personality, let’s see how taste perception can influence our mood and behaviors. An example study by Vi and Obrist (2018) showed that those experiencing a sour taste were more likely engage in risk-taking. This was measured using the standardized Balloon Analogue Risk-Taking (BART) task, a computerized gambling task. Participants were asked to virtually pump up a balloon on a computer screen, with an accumulated monetary reward at stake. After each pump, the balloon either explodes or increases in size based on a randomized algorithm, yielding greater reward. Participants who had tasted something sour (as compared to a neutral water stimulus) were more likely to keep inflating the virtual balloon, risking the loss of the reward.

A study exploring the interrelation between taste perception and mood (Chan et al., 2013) showed that tasting something sweet made people feel temporarily more romantic. And that by having people remember an episode of romantic love, they would report some foods as being sweeter than did those who were asked to recall a jealous memory.

In another study by Ren et al., (2014), researchers exposed a group of participants to the sweet taste of Oreo cookies. This exposure resulted in a greater interest in initiating relationships with a potential partner.

A study by Greimel et al., (2006) found that prompting people to remember being mistreated at work resulted in bitter tastes being rated as more intense, while watching a joyful film clip (compared to a sad movie clip) resulted in participants rating a sweet drink as more pleasant.

Taste Perception and Clinical Disorders

Some research on taste perception in the context of mental health shows that depressed patients have differences in perception of taste. While some studies have reported no difference in taste perception in depressed patients (Arrando, 2015; Nagai, et al., 2015), researchers Hur et al. (2018) found that the prevalence of altered smell and taste among patients with major depressive disorder was 39.8% and 23.7% respectively.

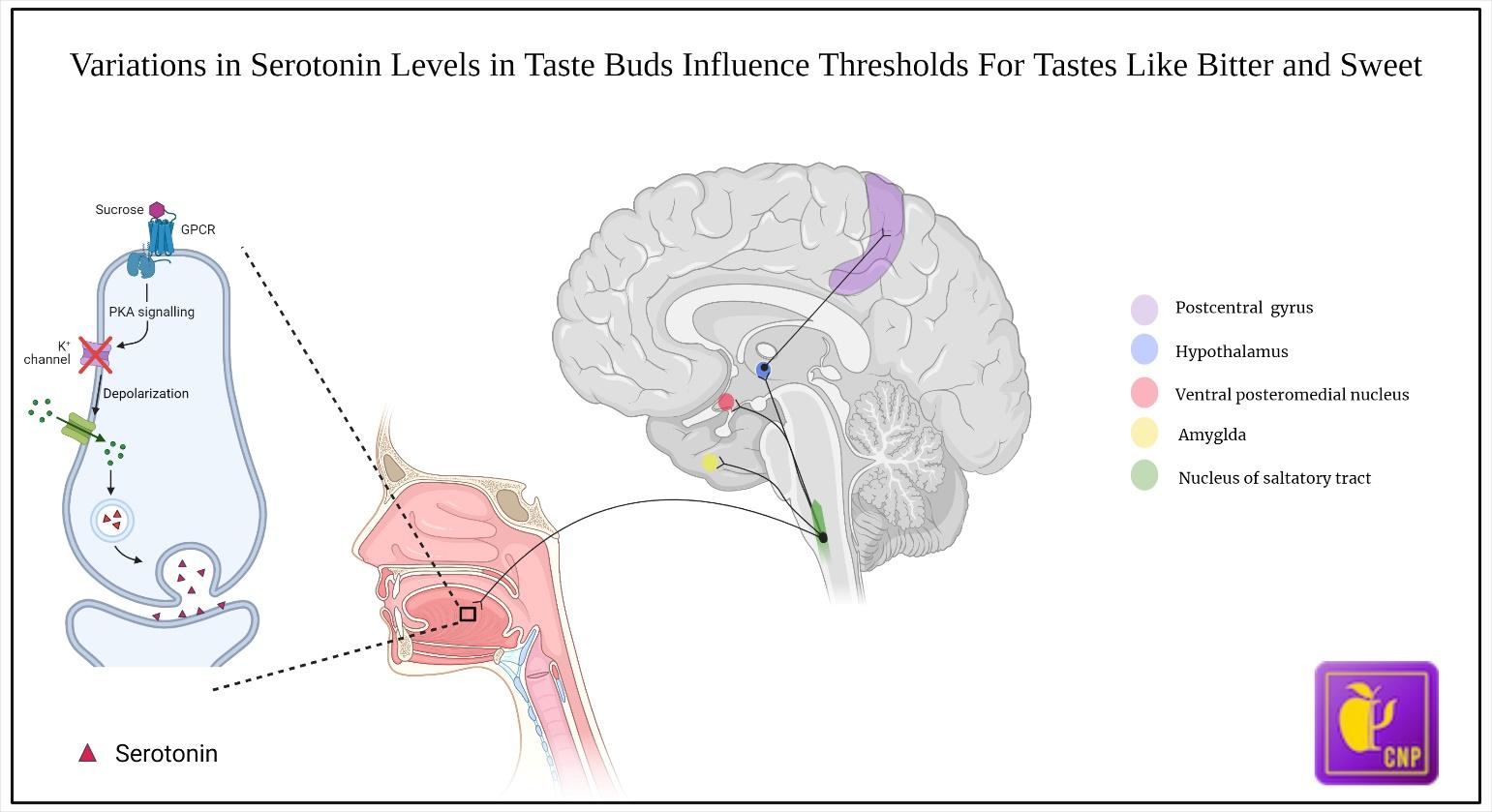

These changes in taste perception are hypothesized to be due to several mechanisms, but one mechanism seems to involve neurochemical changes that happen in our brain due to either emotional or pathological processes (e.g., depression leads to elevation of inflammatory cytokines like interleukin 6). These changes can result in actual changes in the gustatory system.

It is hypothesized that changed taste thresholds could be attributed to reduced serotonin and noradrenaline levels in depressed patients, as suggested by Heath et al. (2006) (Figure 3). This proposed mechanism was supported by another study (Kim et al., 2017), which found reduced expression of 5‐HT1A receptors for serotonin in the taste cells of rats that developed anhedonia — a common symptom of depression. Case reports demonstrate that a change in taste is a neglected symptom in depressed patients that is worthy of further investigation (Miller & Naylor, 1989; Mizoguchi et al., 2012).

Figure 3. Human gustatory pathway. Variations in serotonin levels are associated with different thresholds for certain tastes like bitter and sweet (Heath, 2006).

Research also shows that patients with panic disorders can have exhibited reduced sensitivity to bitterness (DeMet et al., 1989), while anxiety levels are positively correlated with the taste thresholds for bitterness and saltiness (Heath et al., 2006).

According to Hur et al. (2018), it may be advisable for primary care providers to screen their patients for depression or other psychiatric conditions when they report changes in taste or smell.

Conclusion

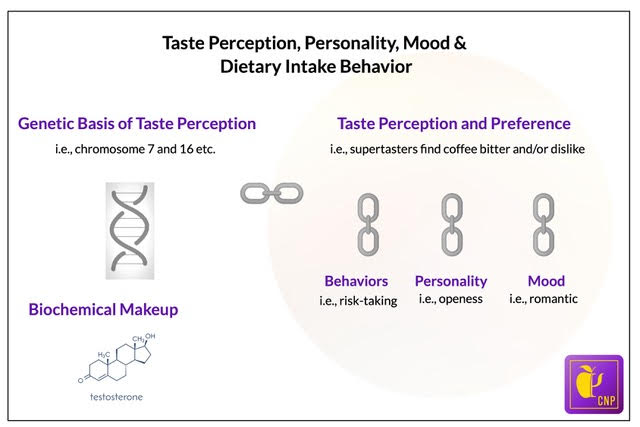

In this article, we’ve had a little ‘taste’ of how our genes influence our taste perception and preferences. The DMHR plot thickens when we begin to be aware of how these perceptions and preferences can interplay with our personality, mood, and behaviors (figure 4).

Figure 4. Interconnections between genes, taste perception, and preference, behaviors, personality, and mood.

For example, we learned how anxious individuals can prefer a narrower range of food while people with personality attributes like openness typically score above average on preferences for new food experiences. Intriguingly, differences in food behavior and taste perception have been linked with circulating levels of certain neurotransmitters like serotonin and can affect taste perception in clinical disorders.

While not lending to a conclusive understanding of the factors involved in dietary intake, our goal with this article is to provide you with a new awareness of the interconnection that occurs between your genes, personality, emotions, and food-related behaviors and preferences.

To learn more, visit the CNP Diet and Personality and Diet and Sensory-Perception research categories in the NPRL.

References

Arrondo, G., Murray, G. K., Hill, E., Szalma, B., Yathiraj, K., Denman, C., & Dudas, R. B. (2015). Hedonic and disgust taste perception in borderline personality disorder and depression. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science, 207(1), 79–80. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.150433

Bègue, L., Bricout, V., Boudesseul, J., Shankland, R., & Duke, A. A. (2015). Some like it hot: Testosterone predicts laboratory eating behavior of spicy food. Physiology & Behavior, 139, 375–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2014.11.061

Chan, K. Q., Tong, E. M. W., Tan, D. H., & Koh, A. H. Q. (2013). What do love and jealousy taste like? Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 13(6), 1142–1149. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0033758

Conner, T. S., Thompson, L. M., Knight, R. L., Flett, J. A. M., Richardson, A. C., & Brookie, K. L. (2017). The role of personality traits in young adult fruit and vegetable consumption. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(FEB). https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2017.00119

DeMet, E., Stein, M. K., Tran, C., Chicz-DeMet, A., Sangdahl, C., & Nelson, J. (1989). Caffeine taste test for panic disorder: Adenosine receptor supersensitivity. Psychiatry Research, 30(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90014-0

Greimel, E., Macht, M., Krumhuber, E., & Ellgring, H. (2006). Facial and affective reactions to tastes and their modulation by sadness and joy. Physiology & Behavior, 89(2), 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2006.06.002

Heath, T. P., Melichar, J. K., Nutt, D. J., & Donaldson, L. F. (2006). Human taste thresholds are modulated by serotonin and noradrenaline. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(49), 12664–12671. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3459-06.2006

Hur, K., Choi, J. S., Zheng, M., Shen, J., & Wrobel, B. (2018). Association of alterations in smell and taste with depression in older adults. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology, 3(2), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/LIO2.142

Kim, D., Chung, S., Lee, S. H., Koo, J. H., Lee, J. H., & Jahng, J. W. (2017). Decreased expression of 5-HT1A in the circumvallate taste cells in an animal model of depression. Archives of Oral Biology, 76, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ARCHORALBIO.2017.01.005

Mascie-Taylor, C. G. N., McManus, I. C., MacLarnon, A. M., & Lanigan, P. M. (1983). The association between phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) tasting ability and psychometric variables. Behavior Genetics, 13(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01065667

Meier, B. P., Moeller, S. K., Riemer-Peltz, M., & Robinson, M. D. (2012). Sweet taste preferences and experiences predict prosocial inferences, personalities, and behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(1), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0025253

Mizoguchi, Y., Monji, A., & Yamada, S. (2012). Dysgeusia successfully treated with sertraline. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.NEUROPSYCH.11040095

Nagai, M., Matsumoto, S., Endo, J., Sakamoto, R., & Wada, M. (2015). Sweet taste threshold for sucrose inversely

Neuroscientist News. (2022, June 14). Do our genes determine what we eat? https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-taste-perception-20833/

correlates with depression symptoms in female college students in the luteal phase. Physiology & behavior, 141, 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.01.003

Otis, L. P. (1984). Factors influencing the willingness to taste unusual foods. Psychological Reports, 54, 739–745.

Ren, D., Tan, K., Arriaga, X. B., & Chan, K. Q. (2014). Sweet love: The effects of sweet taste experience on romantic perceptions. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/0265407514554512, 32(7), 905–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514554512

Smith, W., Powell, E. K., & Ross, S. (1955). Manifest anxiety and food aversions. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 50(1), 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0049253

Supertaster – APA dictionary of psychology. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://dictionary.apa.org/supertaster

Spence C. (2021). What is the link between personality and food behavior?. Current research in food science, 5, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.12.001

Vi, C. T., & Obrist, M. (2018). Sour promotes risk-taking: An investigation into the effect of taste on risk-taking behaviour in humans. Scientific Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-018-26164-3