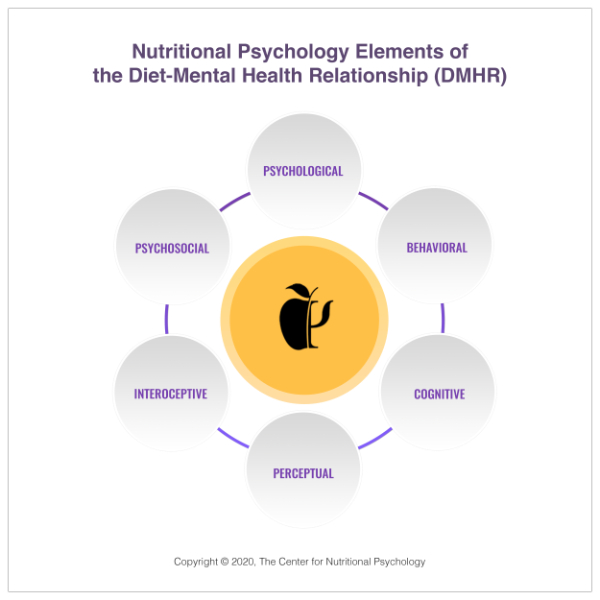

Today’s food landscape is full of sensory-perceptual cues that can drive us to consume high-calorie, energy-dense foods (Ravussin & Ryan, 2018). The abundance of these food cues is believed to be one of the main drivers of food overconsumption (Charbonnier, 2018), as is the availability of high-calorie, energy-dense foods. Exposure and availability are two concepts within nutritional psychology shown to influence our dietary intake behaviors and patterns.

Exposure to high-calorie, energy-dense food cues invoke a host of psychological, cognitive, behavioral, sensory-perceptual, and interoceptive processes that affect our response to these foods. This can be particularly true for those with obesity (Chao et al., 2020). The cognitive process associated with learning and memory involve the hippocampus — which is one of the structures in our brain found to be particularly vulnerable to the influence of high-calorie, energy-dense foods.

What does memory have to do with our response to food cues in our environment? Studies show that memories can influence our future food seeking for highly palatable and remembered food experiences. Let’s explore how these memories influence our response to food cues in our environment, particularly when related to memories of events we find stressful, or foods we remember as preferred.

Many situations that cause people to recall memories from their past are related to food.

Humans become conditioned to respond to food-related cues that are informed by past memory associations with previous food experiences. For example, an individual may start to associate stressful events with the feeling of reward experienced after eating high-calorie foods. Once this association is learned, encountering that same food stimulus can induce the same physiological and behavioral responses as previously experienced, including salivation, hunger, and ultimately repeated food intake (Chao et al. 2020).

A study by Chao et al. in 2020 examined whether briefly exposing individuals to their personal favorite foods or to an event they personally find stressful, would impact their hunger, anxiety, and food intake, compared with exposing them to cues that are considered ‘neutral’ to them.

Since it was hypothesized that the obese participants would have greater responses to cues than ‘normal weight’ participants, the researchers also investigated whether cue responses of hunger and food intake differed by weight status. Participants recruited were 18 to 45 years old and scored less than 40 on the BMI scale (30 and above is classified as obese).

It was hypothesized that the obese participants would have greater responses to cues than ‘normal weight’ participants.

‘Scene imagination’ questionnaires were used to find out more about the participants’ recent life events, helping to create personalized imagery scripts indicating participant’s personal stressors, favorite foods, and the cues they deemed neutral. Audiotapes were recorded using these structured and personalized scripts, and were played during the 3-day laboratory experiments to reproduce the same stressful, food, or neutral situation. In these sessions, participants were given headphones to listen to different audio recordings of these cues each day.

After each scene imagination session, each person was given free access to a buffet consisting of high-calorie snack foods such as chips, cookies, and brownies, as well as low-calorie snack alternatives including carrots and grapes. After an hour, the snack tray was carried away and examined to measure how much the person had eaten.

The results showed that food cues induced hunger to a significantly greater extent than the neutral and stress stimuli. But the weight class of the individual did not have an impact on the level of hunger evoked by food cues. A similar number of calories were consumed across the three stimuli. However, a difference was observed in the type of snacks mostly eaten by certain individuals after listening to the food and stress cue audiotapes.

In response to the food cue, those with obesity sought 81% of their calories from high-calorie snacks, which was significantly higher than ‘normal weight’ participants (63.5%). The obese subjects also recorded a significantly higher percentage intake of calories from calorie-rich snacks than their ‘normal weight’ counterparts following exposure to stress cues. Weight status, however, did not predict how much calorie-rich food a person ate following the neutral cue condition.

Interventions that decrease cue reactivity to food and stress may help obese individuals to cut down on calorie-rich foods.

This study found that obese adults obtained a greater proportion of their calories from high-calorie foods relative to ‘normal weight’ adults in response to food cues and stress, which is in accordance with previously conducted research. While these findings represent the efforts in this study only, they support the notion that people with obesity can be more vulnerable to food cues and stress, leading them to seek out more high-calorie and energy-dense foods. The study authors note that interventions that decrease cue reactivity to food and stress may help obese individuals to cut down on their intake of calorie-rich foods, and in turn, improve their diet-mental health relationship.

References

Chao, A. M., Fogelman, N., Hart, R., Grilo, C. M., & Sinha, R. (2020). A laboratory-based study of the priming effects of food cues and stress on hunger and food intake in individuals with obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 28(11), 2090–2097. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22952

Charbonnier, L., van Meer, F., Johnstone, A. M., Crabtree, D., Buosi, W., Manios, Y., Androutsos, O., Giannopoulou, A., Viergever, M. A., Smeets, P., & Full4Health consortium (2018). Effects of hunger state on the brain responses to food cues across the life span. NeuroImage, 171, 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.012

Ravussin, E., & Ryan, D. H. (2018). Three New Perspectives on the Perfect Storm: What’s behind the obesity epidemic?. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 26(1), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22085

Stevenson, R., Francis, H., Attuquayefio, T., Gupta, D., Yeomans, M., Oaten, M., & Davidson, T. (2020) Hippocampal-dependent appetitive control is impaired by experimental exposure to a Western-style diet. Royal Society Open Science, 7(2).