Eating Fermented Foods with Live Microbes May Improve Dietary Health

Fermented foods—like kimchi and yogurt—and probiotic supplements have been associated with improved metabolic health and, consequently, stronger immunity and reduced risk against various cancers (Savaiano et al., 2021; Wastyk et al., 2021). What these foods and supplements have in common is the presence of living microorganisms (Montville, 2004; Jeddi et al., 2014; Ziyaina et al., 2018). In fact, raw and unpeeled fruits and vegetables, dairy, and certain proteins contain dietary microbes that have been demonstrated to benefit human health (Roselli et al., 2021; Marco et al., 2022).

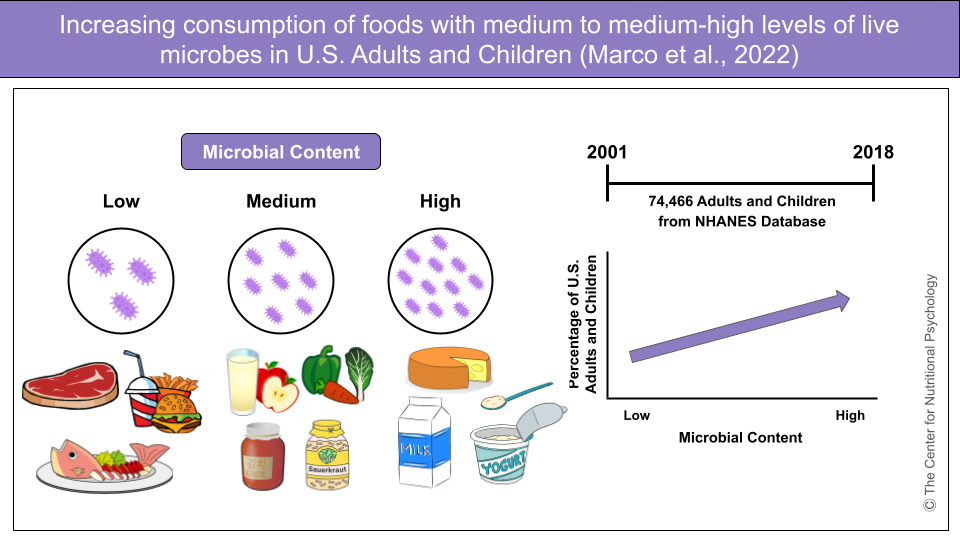

Note: this article/study does not specifically explore beneficial or pathogenic microbes; rather, the authors are interested in determining how many “live” microbes are found in foods within the Western diet. To do this, they used preexisting data to estimate microbial content by classifying the foods eaten by participants as low, medium, or high amounts.

Raw and unpeeled fruits and vegetables, dairy, and certain proteins contain dietary microbes that have been demonstrated to benefit human health.

However, compared to other macronutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins which are reported on nutrition fact labels and databases, it is not clear how much of the Western diet is actually composed of foods containing live dietary microbes and, moreover, the percentage of U.S. adults and children who consume them. Addressing this knowledge gap is not only imperative in establishing safe daily intake values of live microbes but also encourages further clinical studies to investigate the long-term health benefits they may provide.

To quantify the level of microbes across food groups and the proportion of U.S. residents that ingest them, Marco et al. conducted a 2022 study that analyzed published dietary data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), an ongoing study led by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES study participants are selected through statistical sampling and information is collected through both in-home interviews and physical examinations at designated health centers.

For their retrospective analysis, Marco et al. used 24-hour dietary recall results obtained from 74,466 adults and children, dating from 2001 to 2018. Their study aimed to use pre-existing data to estimate the general amounts of microbes contained in food items reported in the NHANES study, classify each item as low-, medium-, or high-microbial content, and, ultimately, approximate the percentage of U.S. adults and children who consume these live microbes.

Figure 1. Representative image depicting the approximate levels of live microbes across different food groups and the increasing U.S. dietary intake of medium to medium-high levels of microbes from 2001 to 2018 (based on Marco et al., J Nutr, 2022).

They estimated that processed foods (which are usually pasteurized to remove harmful microbes), meats, seafood (raw and cooked), and peeled fresh fruits and vegetables contained low levels of microbes. Fruit juices, unpeeled fruits and vegetables (skin is still on, so microbes can live on the surface), and fermented foods like sauerkraut, miso, and kimchi have medium levels. Fermented and cultured dairy products like milk, yogurt, sour cream, and cheese were classified as high (Figure 1).

Processed foods (which are usually pasteurized to remove harmful microbes), meats, seafood (raw and cooked), and peeled fresh fruits and vegetables contained low levels of microbes.

While their study attempted to categorize different food groups based on their microbial content through previous studies and expert opinions, Marco et al. recognize that their findings are limited by possible biases and inaccuracies in how items were classified. Nevertheless, after quantifying the levels of microbes across different foods in the Western diet, the authors approximated that greater than 50% of U.S. adults and children eat medium to medium-high amounts of live microbes, with this being an increasing trend over an 18-year period (Marco et al., 2022).

Out of all food groups categorized, fruits, vegetables, and fermented dairy constituted the majority of live microbes in the U.S. diet based on the study’s classification system. Despite the numerous approaches and regulatory guidelines implemented to clean fruits and vegetables for human consumption, Marco et al. report them to be a notable source of microbes that can actually be providing key nutrients such as calcium, fiber, and potassium, which are lacking in the diets of adults and children (USDA and USDHHS, 2020).

Out of all food groups categorized, fruits, vegetables, and fermented dairy constituted the majority of live microbes in the U.S. diet.

This result is not surprising but underscores the need for further research on the validity of the study’s approach and the significance of these microbes on fruits and vegetables. In comparison, the authors expected fermented dairy products to be the major source of microbes as the process of fermentation—in which foods composed of carbohydrates convert to alcohol or organic acids used in various cuisines—relies on the biological activities of microorganisms. Ultimately, Marco et al. presented interesting results that provide a foundation for future research to better explore the relationship between the consumption of live microbes and dietary health outcomes.

References

Jeddi, M. Z., Yunesian, M., Gorji, M. E., Noori, N., Pourmand, M. R., & Khaniki, G. R. (2014). Microbial evaluation of fresh, minimally-processed vegetables and bagged sprouts from chain supermarkets. Journal of health, population, and nutrition, 32(3), 391–399.

Marco, M. L., Hutkins, R., Hill, C., Fulgoni, V. L., Cifelli, C. J., Gahche, J., Slavin, J. L., Merenstein, D., Tancredi, D. J., & Sanders, M. E. (2022). A Classification System for Defining and Estimating Dietary Intake of Live Microbes in US Adults and Children. The Journal of nutrition, nxac074. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxac074

Montville, R., & Schaffner, D. W. (2004). Statistical distributions describing microbial quality of surfaces and foods in food service operations. Journal of food protection, 67(1), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-67.1.162

Roselli, M., Natella, F., Zinno, P., Guantario, B., Canali, R., Schifano, E., De Angelis, M., Nikoloudaki, O., Gobbetti, M., Perozzi, G., & Devirgiliis, C. (2021). Colonization Ability and Impact on Human Gut Microbiota of Foodborne Microbes From Traditional or Probiotic-Added Fermented Foods: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in nutrition, 8, 689084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.689084

Savaiano, D. A., & Hutkins, R. W. (2021). Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: a systematic review. Nutrition reviews, 79(5), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa013

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

Wastyk, H. C., Fragiadakis, G. K., Perelman, D., Dahan, D., Merrill, B. D., Yu, F. cactusmeraviglietina.it B., Topf, M., Gonzalez, C. G., Van Treuren, W., Han, S., Robinson, J. L., Elias, J. E., Sonnenburg, E. D., Gardner, C. D., & Sonnenburg, J. L. (2021). Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell, 184(16), 4137–4153.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019

Ziyaina, M., Govindan, B. N., Rasco, B., Coffey, T., & Sablani, S. S. (2018). Monitoring Shelf Life of Pasteurized Whole Milk Under Refrigerated Storage Conditions: Predictive Models for Quality Loss. Journal of food science, 83(2), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.13981

Leave a comment