Due to the aging world population, the number of people with cognitive impairment will have doubled by the year 2035. In addition, the number of individuals with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) will increase substantially. Common denominators of these comorbidities are impaired vascular function and metabolic health. In this short article, we take a look at the connection between vascular health and cognitive function in the context of lifestyle factors, including nutrition. This connection is one of many within the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR), which nutritional psychology encompasses. The research discussed has been conducted by the Physiology of Human Nutrition (PHuN) research group in the Department of Nutrition and Movement Sciences at Maastricht University.

The number of people with cognitive impairment will double by 2035.

Compared to the wealth of knowledge on the effects of dietary factors on peripheral vascular function and the risk of CVD and T2DM, not much is known about the effects of diet on brain vascular and metabolic health, and cognitive performance. This is of utmost interest since the brain is one of the most metabolically active organs. Impaired brain metabolic health is associated with cognitive decline, while impaired brain vascular function is a major pathophysiological factor preceding the development of dementia.

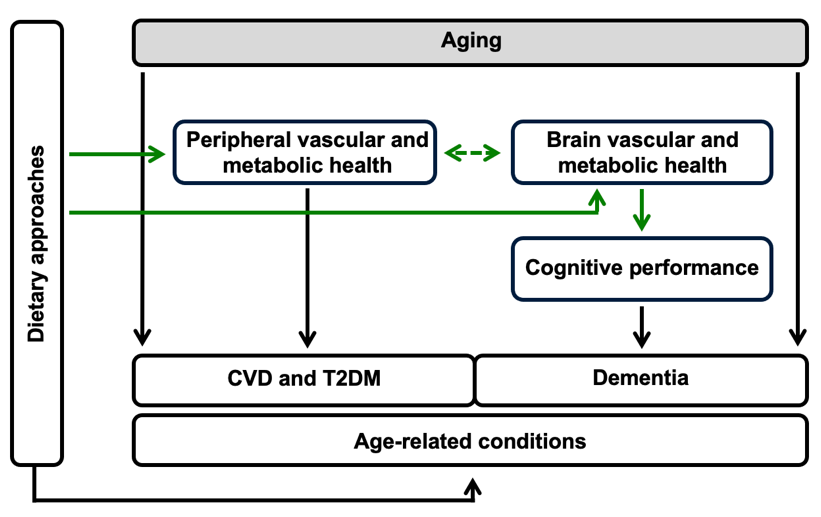

Although a healthy lifestyle protects against cognitive impairment, it’s not known whether these brain markers are sensitive to dietary interventions to prevent or slow cognitive impairment and the development of dementia. The specific assessment of brain metabolic health — especially in different cognitive-control brain areas — and brain vascular function is thus highly relevant (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Our research investigates the effects of dietary approaches on peripheral vascular and metabolic health, the risk of developing age-related conditions including CVD and T2DM, and the potential for dietary changes to improve brain health and cognitive performance (which can reduce the risk of dementia).

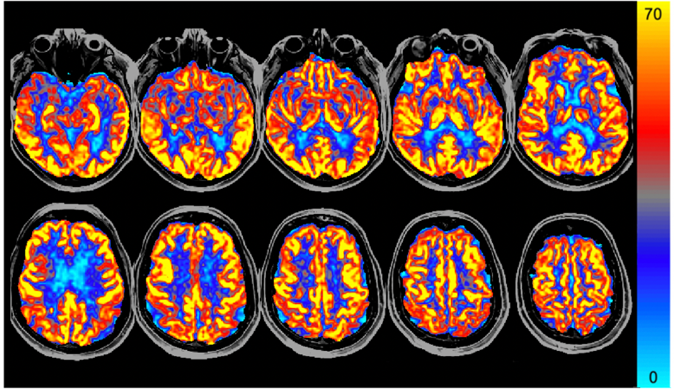

Figure 2. Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) cerebral blood flow (CBF) map in units of milliliters of blood per 100 grams of human brain tissue per minute (mL/100g tissue/min).

Methods

The research performed at the Physiology of Human Nutrition (PHuN) research group at the Department of Nutrition and Movement Sciences at Maastricht University involves well-defined nutritional intervention trials that are designed to assess the effects of diet on brain (vascular) health and cognitive performance. Intervention effects are studied using innovative and emerging non-invasive brain MRI methods based on Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) perfusion contrast, which have provided means of probing metabolic effects in the brain, revealing brain metabolic health. Our findings show that cerebral blood flow (see Figure 2) can be considered a sensitive straightforward marker of brain vascular function, which strongly correlates with cognitive performance.

Of note, lower cerebral blood flow is associated with accelerated cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia in the general population. Cerebral blood flow is quantified by the non-invasive gold standard, which is the MRI perfusion technique pseudo-continuous ASL. In older adults, aging accounts for a decrease of about 0.45% to 0.50% in global cerebral blood flow per year. We therefore primarily focus on older men and women who are known to be at increased risk of cognitive impairment.

Lower cerebral blood flow is associated with accelerated cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia.

Finally, cognitive performance is studied using the neuropsychological test battery CANTAB. These validated assessments for state-of-the-art cognitive performance testing focus on the main cognitive domains (i.e. attention, memory and executive function).

Findings

In a published literature review (see reference 1), we have summarized the impact of dietary factors and exercise on brain vascular function in adults and discussed the relationship between these effects with changes in cognitive performance. We conclude that lifestyle factors, including diet and physical exercise, can improve brain vascular function which may contribute to the beneficial effects observed on cognitive performance. Indeed, in a recent study, we determined that aerobic exercise training improves regional cerebral blood flow in sedentary older men (2). These changes in cerebral blood flow may underlie exercise-induced beneficial effects on executive function.

Diet and physical exercise can improve brain vascular function which may contribute to cognitive performance.

Recently, in another randomized, controlled crossover trial in older adults, the longer-term effects of soy nut consumption on brain vascular function and cognitive performance were investigated (3). We observed an increased regional cerebral blood flow following intake of soy nuts, which are not only rich in proteins but also in other potential bioactive ingredients. In fact, cerebral blood flow increased in four brain clusters located in the left occipital and temporal lobes, bilateral occipital lobe, right occipital and parietal lobes, and left frontal lobe which is part of the ventral network. These four regions are involved in psychomotor speed performance, which also improved as the movement time was reduced.

Relevance

The medical, psychosocial, and economic consequences of impaired cognitive performance in the context of the aging population will require multilevel assessments and multidimensional solutions. Effective dietary and evidence-based intervention and prevention strategies are therefore urgently needed.

Beyond its scientific relevance, the outcomes of such research will contribute to other important areas. Dietary approaches, which can be implemented at relatively low costs by the aging world population, could scale down medical costs and therefore have significant societal and economic relevance. These studies are important from a consumers’ perspective as well as from an economic and public health point of view (e.g. health care costs, integrated dietary/lifestyle interventions, and dietary recommendations).

Empirical evidence on how nutrition interrelates with metabolic, vascular, and cognitive health supports our understanding of the DMHR as a whole and holds promise for future health-centric interventions.

Visit the Diet and Aging and Diet and Brain Research Categories in the NPRL to learn more about how these factors interconnect.

References

Joris, P. J., Mensink, R. P., Adam, T. C., & Liu, T. T. (2018). Cerebral blood flow measurements in adults: A review on the effects of dietary factors and exercise. Nutrients, 10. doi: 10.3390/nu10050530.

Kleinloog, J. P. D., Mensink, R. P., Ivanov, D., Adam, J. J., Uludag, K., & Joris, P.J. (2019). Aerobic exercise training improves cerebral blood flow and executive function: A randomized, controlled cross-over trial in sedentary older men. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 11(333). doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00333.

Kleinloog, J. P. D., Tischmann, L., Mensink, R. P., Adam, T. C., & Joris, P. J. (2021). Longer-term soy nut consumption improves cerebral blood flow and psychomotor speed: results of a randomized, controlled crossover trial in older men and women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab289.