The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version 5, DSM-5 for short, classifies autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disabilities, specific learning disorders, communication disorders, and motor disorders as neurodevelopmental disorders, or NDDs. This cluster of disorders is associated with abnormal brain development and impairments in cognition, speech and language skills, and social-emotional functioning.

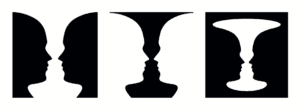

A common feature of Neurodevelopmental Disorders or NDDs involves changes in synaptic plasticity in the brain. Synaptic plasticity is the brain’s process of modifying synaptic transmission in response to experiences and stimuli.

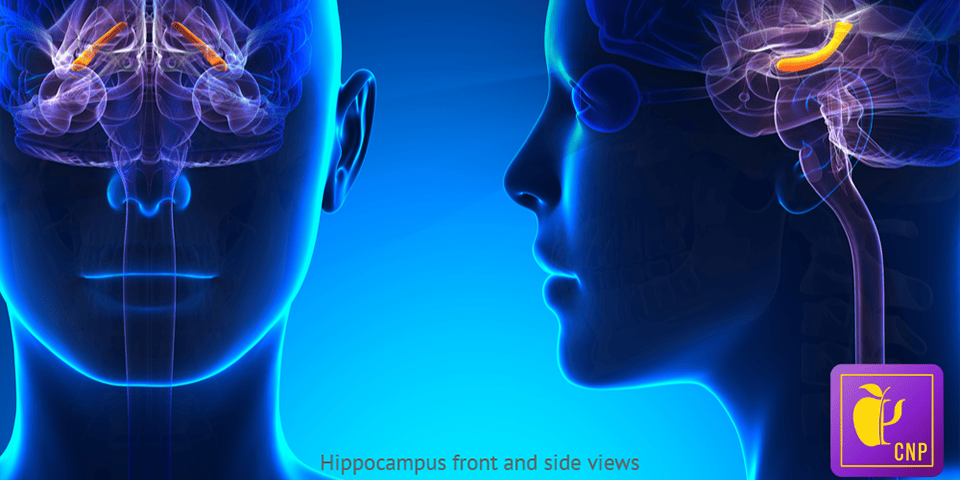

While the underlying molecular mechanisms associated with changes in synaptic plasticity are only partially understood, lifestyle factors, like diet, also impact synaptic plasticity. In juvenile mice studies, a high-fat diet contributed to decreased hippocampal neurogenesis, impaired synaptic and cognitive function, and poor memory. By examining the molecular mechanisms affected by a high-fat diet, defined as a diet with a 30-50% fat content, Penna and his colleagues suspected there’s potential for understanding the molecular mechanisms associated with NDDs.

Based on their review of study findings, Penna and his colleagues developed a diagram to illustrate potential molecular mechanisms connecting metabolic dysfunction of a high-fat diet to synaptic plasticity deficits related to NDDs.

A chronic, high-fat diet contributes to low-grade inflammation in the body. Persistent activation of the body’s inflammatory response system leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines and other hormones into the bloodstream. This results in neuroinflammation.

An associated dysfunction of neuroinflammation is changes in synaptic plasticity. These changes could be brought on by dysregulated local protein synthesis. In mice studies, a decrease in Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) — a neutrophin impacting synaptic transmission, was detected after consumption of a high-fat diet. The resulting hypothesis is that lowered levels of BDNF may lead to lowered protein synthesis at the synapse. This contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction, which is linked to neuroinflammation and alterations in synaptic plasticity found in NDDs and the effects of a high-fat diet.

References

Penna, E., Pizzella, A., Cimmino, F., Trinchese, G., Cavaliere, G., Catapano, A., Allocca, I., Chun, J. T., Campanozzi, A., Messina, G., Precenzano, F., Lanzara, V., Messina, A., Monda, V., Monda, M., Perrone-Capano, C., Mollica, M. P., & Crispino, M. (2020). Neurodevelopmental disorders: Effect of high-fat diet on synaptic plasticity and mitochondrial functions. Brain Sciences, 10(11), 805. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7694125/