Nutritional Psychology Influences of Diet on Perception

The global diabetes prevalence in 2019 is estimated to be 9.3% (463 million people), rising to 10.2% (578 million) by 2030 and 10.9% (700 million) by 2045.1 While diabetes is generally approached from a biomedical model, this study demonstrated that psychological and perceptual factors can significantly influence our physiology when it comes to blood glucose levels.

Let’s begin by understanding the process of human perception. What is perception? For the purpose of understanding the study at hand, perception involves 1) the taking in of information through our senses (i.e., our eyes or ears) and 2) our brain’s interpretation of this information into something that has personal meaning. An example would be our perception of the color red being “hot”, or the color green meaning “go”.

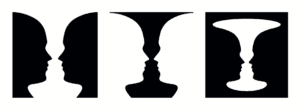

Peoples’ perceptions differ for several reasons, and we each ascribe a different meaning to the same objects, smells, sights, sounds, and feelings, and sensations. A classic example of perception used in psychology involves the figure/foreground ‘face or cup’ illustration. Do you see two faces in these images or a cup?

Figure 1. Perception Illustration: Face or Cup?

Study

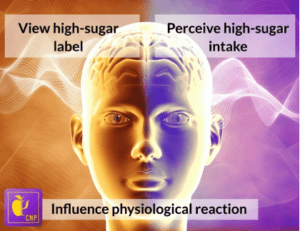

This study examined whether our perception of how much sugar a drink contained (as indicated by its label) could influence our physiological response to that drink. The study involved: 1) a diabetic patient population, 2) food labels listing different amounts of sugar in a juice drink (all contained the same amount), and 3) examination of the psychological and perceptual factors influencing the participants’ physiological reactions in response their perception of how much sugar was in the drink.

In other words, can our perception of the amount of sugar shown on a drink label affect our physiological reaction to that drink?

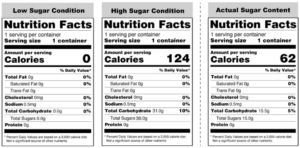

Thirty participants with type 2 diabetes were divided into two groups and given a sugar-sweetened beverage. One group was shown a nutrition label that reported zero grams of sugar in the beverage, while the other was shown a nutrition label that reported 30 grams of sugar. In reality, all participants received the same exact beverage containing 15 grams of sugar.

Figure 2. The experiment’s manipulated nutrition labels2

The team measured blood glucose levels 4 times throughout the experiment: immediately before consumption and 20, 40, and 60 minutes after consumption.

Findings

They found that the participants who were shown the high sugar label had higher levels of glucose in their bloodstream than those who thought they were drinking a sugar-free beverage. Meaning that the participants’ blood glucose values changed exclusively due to their psychological perception of the sugar content, rather than the amount of sugar they actually consumed.

Perception of sugar intake influenced physiological reaction

While study results showed that just the perception of sugar content affected changes in diabetic participants’ blood glucose levels, it also revealed that their perception of how much sugar was included in the drink was influenced by their underlying emotional processes.

Namely, those whose blood glucose levels increased the most in response to the drink’s perceived sugar content, were those who were influenced more by external cues in their environment — like whether it was time to eat, or if other people were eating. Those who were driven more by their internal (or interoceptive) cues of hunger, had a more accurate perception of the drink’s actual sugar content. And this more accurate perception was more aligned with an accurate physiological response to the drink’s sugar content.

Conclusion

These findings help us understand that psychological and physiological processes aren’t independent of each other like we originally thought. See the CNP Diet-Mental Health Break created on this study in the CNP Video Research Library. We thank Dr. Chanmo Park for his personal support in providing editing assistance for the DMHB script.

Citations

1. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168822719312306

2. Park, C., Pagnini, F., & Langer, E. (2020). Glucose metabolism responds to perceived sugar intake more than actual sugar intake. Scientific reports,10(1), 15633.

Leave a comment