Editor’s Note: We begin our three-part series with an overview of the nine common characteristics that underlie Blue Zones. The second article will dive deeper into how diet and mental health may impact longevity.

In 2016, to explore the secrets to longevity, National Geographic Fellow and American Author Dan Buettner located five geographic locations on Earth yielding higher-than-average populations of people living beyond 100 years old, referred to as “centenarians.” The locations are Ikaria, Greece; Okinawa, Japan; Sardinia, Italy; Loma Linda, California; and Nicoya, Costa Rica (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). Buettner coined the term “Blue Zones,” defining them as communities that produce individuals who are ten times more likely to reach age 100 than the average

US citizen and prompting questions about what contributes to such extraordinarily healthful aging (Buettner & Skemp, 2016).

Blue zones are communities that produce individuals who are ten times more likely to reach age 100 than the average US citizen.

With the help of demographers, scientists, and anthropologists, Buettner identified nine common lifestyle characteristics among the Blue Zones that impact longevity: the Power 9 (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). These include: move naturally, purpose, downshift, 80% rule, plant slant, wine at 5, right tribe, loved ones first, and belong (Figure 1). His idea is that if genes dictate about 20% of life expectancy and lifestyle governs about 80%, the Power 9 can provide a blueprint for creating healthier populations and a higher human life expectancy worldwide (Herskind et al., 1996).

Figure 1. Power 9 Blue Zone Characteristics

Power 9 characteristics can be sorted under four umbrella components — move naturally, right outlook, eat wisely, and connect.

Component 1: Move Naturally

Rather than engaging in the exercise habits commonly seen in Western culture (e.g., high-intensity cardio, weight-lifting, marathon running), Blue Zone residents live in environments that foster daily, mindless movement. For example, Sardinians, often employed as shepherds, walk around five miles a day or more in tending to their animals (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). For others in Blue Zone communities, this routine movement may look like tending to a garden or walking across town for social commitments.

Rather than engaging in the exercise habits commonly seen in Western culture, Blue Zone residents live in environments that foster daily, mindless movement.

This movement leads to positive mental and physical outcomes. For instance, a 2021 study concluded that the more time Sardinians spent gardening, the better physical health they reported (Ruiu et al., 2022). The takeaway? Exceptionally long-living individuals move their bodies daily and in intuitive ways.

Component 2: Right Outlook

Purpose

While the idea of “finding purpose” may hold varying names — the Okinawans call it “Ikiagi” and the Nicoyans call it “plan de Vida,” for example — the concept serves as a central theme within Blue Zones (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). Both “Ikiaki” and “plan de Vida” translate loosely to “why I wake up in the morning,” implying recognition of a life purpose. Buettner and Skemp (2016) found that having a life purpose may be worth up to seven years of additional life expectancy, which was supported by an association between a stronger purpose in life and decreased mortality found in a later study (Alimujiang et al., 2019). The discovery of such an individualized purpose appears to play a central role in the longevity of Blue Zone residents.

Both “Ikiaki” and “plan de Vida” translate loosely to “why I wake up in the morning,” implying recognition of a life purpose.

Downshift

Downshift explores the idea of routines meant to release stress. The experience of stress is inevitable, and Blue Zone residents have created ways — unique to their religious ties and geographic regions — to release stress. For example, Adventists in Loma Linda pray, Okinawans take moments to remember their ancestors, and Ikiarians nap (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). In creating rituals to eliminate distress, bitcoin mixer individuals in Blue Zone regions defend themselves against stress-related illnesses such as coronary heart disease, cancer, and respiratory disorders (Salleh, 2008). By prioritizing outlets of escape from ambient stressors through downshift, Blue Zone residents create a culture supportive of a greater-than-average life expectancy.

Downshift explores the idea of routines meant to release stress.

Component 3: Eat Wisely

80% Rule

Rather than eating until they feel they can’t take another bite, Blue Zone residents follow an 80-20 rule. This mantra, Hara Hachi Bu, created by Okinawans 2,500 years ago, encourages individuals to stop eating when they are 80% full (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). A consistent practice of this rule leads this population to consume fewer calories and consequently have lower energy intake (Fukkoshi et al., 2015).

The Okinawan mantra Hara Hachi Bu encourages individuals to stop eating when they are 80% full.

This practice begs individuals to practice mindfulness, as recognizing one’s satiety requires an understanding of internal cues. Blue Zone residents are encouraged to chew slowly, take deep breaths, and be present in their bodies to honor their hunger cues and avoid overeating. As stated above, by not overeating, these populations subsequently experience a lower input of calories and collateral energy, which is associated with human longevity (Willcox et al., 2006).

In eating until 80% full, Blue Zone residents are pushed to chew slowly, take deep breaths, and be present in their bodies to honor their hunger cues and avoid overeating.

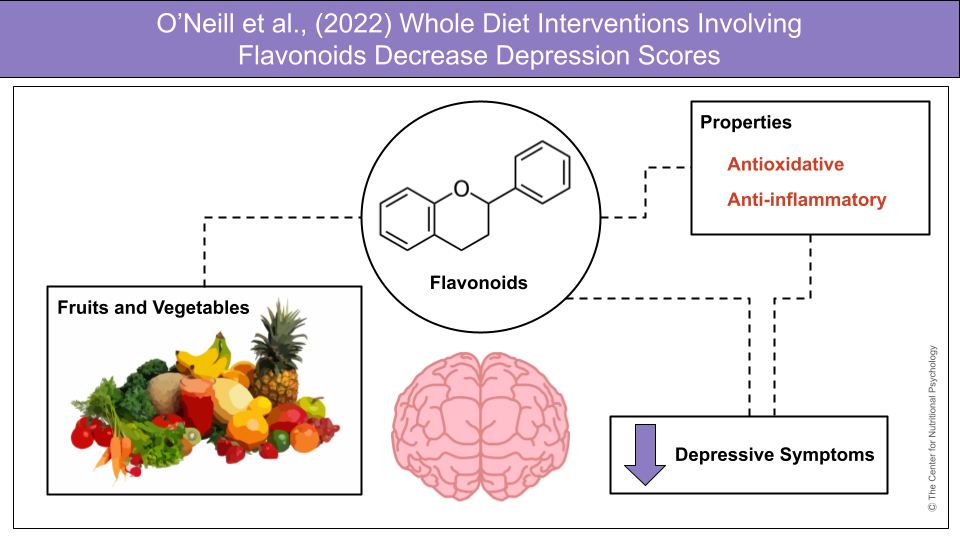

Wine at 5

All Blue Zone populations, excluding Adventists in Loma Linda, regularly and moderately consume alcohol (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). The frequent alcohol of choice is wine, specifically, Cannonau, a red wine native to Sardinia (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). Red wine contains large amounts of antioxidants — polyphenols — which stabilize free radicals and counteract oxidative stress. The latter is a known contributor to detrimental neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression, all of which contribute to increased mortality (Pizzino et al., 2017). Consuming quality red wine regularly and socially provides an influx of antioxidants to help defend against such diseases, likely positively contributing to longer-than-average life spans among Blue Zone residents.

Red wine contains large amounts of antioxidants — polyphenols — which stabilize free radicals and counteract oxidative stress.

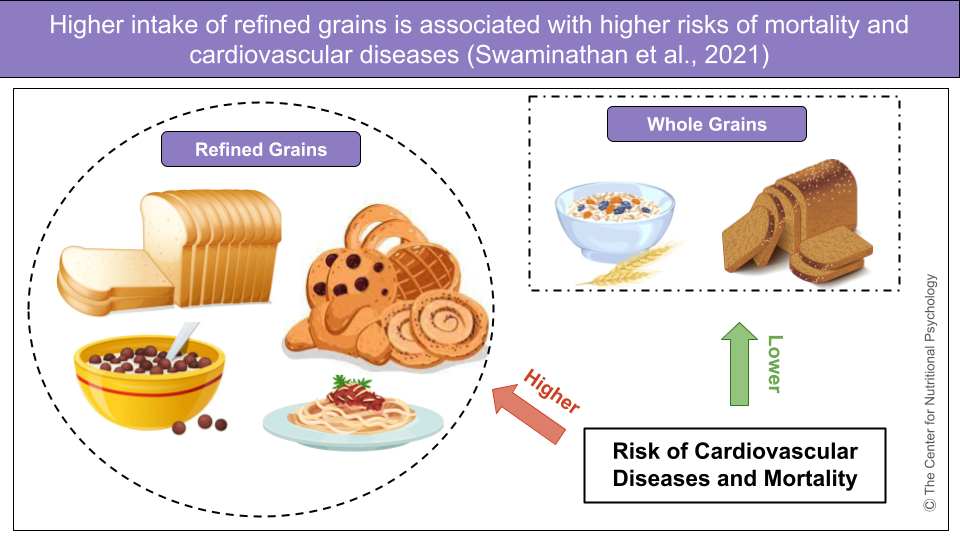

Plant Slant

Most centenarian diets are plant-based, with a significant intake of vegetables, beans, and whole grains. Ikarians, largely due to their proximity to the Mediterranean, eat a Mediterranean diet filled with lots of fruit, olive oil, vegetables, and plant-based proteins such as nuts, beans, and seeds. Adventists take their dietary habits from the Bible and consume a vegan diet full of legumes, leafy vegetables, and nuts. Nicoyans consume little to no processed foods and emphasize antioxidant-rich fruits in their diet (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). Though their diets vary slightly based upon location and community values, all Blue Zone diets have a plant-based theme associated with longevity (Norman & Klaus, 2020).

Component 4: Connect

Right Tribe

The idea of “finding your people” is one that lots of individuals strive to achieve. Maintaining satisfying social ties with friends and family and living a socially-oriented lifestyle can decrease feelings of loneliness and contribute to beneficial mental health outcomes (Hitchcott et al., 2017). In Okinawa, children aged five are put into moai, committed social networks that exist indefinitely (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). These social circles provide individuals with the comfort of knowing they will always have support, whether financial, emotional, or otherwise. Nurturing healthy relationships like those in moai substantially increases one’s likelihood of longevity, explaining why this effort is so important for Blue Zone folk (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

Loved Ones First

Another central theme in Blue Zone territories is keeping family close. Blue Zone residents, whether living near family or in intergenerational homes, emphasize investing in their families (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). In collectivist cultures such as Japan, harmonious relationships with family play a role in supporting psychological well-being (Kitayama et al., 2020). The same goes for the strong social support from family members in Italy; it is associated with few depressive symptoms later in life (Carpiniello et al., 1989). Living with aging parents and grandparents in intergenerational homes also lowers children’s disease and mortality rates (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). Prioritizing loved ones plays a role in longevity, as committing to a partner, commonly seen throughout Blue Zones, can add up to three years of life expectancy (Buettner & Skemp, 2016).

Prioritizing loved ones plays a role in longevity and can add up to three years of life expectancy.

Belong

Most centenarians in Blue Zone communities belong to a faith-based community, and all but five of 263 Blue Zone centenarians interviewed by Buettner belonged to a specific one (Buettner & Skemp, 2016). Denomination does not interfere with the impact of belonging to such a community, as religiosity is a protective factor for aging (Krause, 2003). Attending a faith-based service four times per month can add anywhere between four and 14 years of life expectancy. Older adults who gain a sense of meaning in life from religion also tend to report higher levels of mental health benefits such as life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism (Buettner & Skemp, 2016; Krause, 2003). Overall, the longest-living communities tend to incline toward faith-based groups.

Older adults who gain a sense of meaning from religion also report higher levels of mental health benefits such as life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism.

What now?

The association of mental health and longevity, combined with the knowledge that there are pockets of the world producing abnormal amounts of centenarians, urges the exploration of what mental health efforts Blue Zone residents are implementing into their daily lives that may be impacting mortality.

The Power 9 provides distinct factors central to Blue Zone communities. Physical movement, mental health, diet, and social connection appear critical to uncovering the secrets of longevity and well-being. Yet many questions remain to be answered. How much influence does one factor have over the others? What role does food, specifically, play in the mental health of Blue Zone residents?

Physical movement, mental health, diet, and social connection appear critical to uncovering the secrets of longevity and well-being.

More research on Blue Zones is expected in the upcoming years. As our understanding of the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR) evolves and becomes more central to various healthcare settings, Blue Zones may provide a unique opportunity to boost healthy living.

The interplay of diet and mental health and its impact on longevity will be further explored in the context of Blue Zone regions in two upcoming articles.

References

Alimujiang, A., Wiensch, A., Boss, J. (2019) Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50 years. JAMA Network Open, 2(5). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4270

Buettner, D., Skemp, S. (2016). Blue zones: lessons from the world’s longest lived. Sage Journals, 10(5), 318-321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827616637066

Carpiniello B., Carta M. G., Rudas N. (1989). Depression among elderly people. A psychosocial study of urban and rural populations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 80(5), 445–450. Doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03004.x

Fastame, M.C., Hitchcott, P.K., Mulas, I., Ruiu, M., Penna, M.P. (2018). Resilience in elders of the Sardinian blue zone: an explorative study. Behavioral Sciences, 8(3), doi: 10.3390/bs8030030

Fukkoshi, Y., Akamatsu, R., Shimpo, M. (2016). The relationship of eating until 80% full with types and energy values of food consumed. Science Direct, 17, 153-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.001

Herskind, A.M., McGue, M., Holm, N.V., Sorensen, T.I.A., Harvald, B., Vaupel, J.W. (1996). The heritability of human longevity: a population-based study of 2872 Danish twin pairs born 1870-1900. Human Gent, 97(3), 319-323. DOI: 10.1007/BF02185763

Hitchcott, P.K., Fastame, M.C., Ferrai, J., Penna, M.P. (2017). Psychological well-being in Italian families: an exploratory approach to the study of mental health across the adult life span in blue zone. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 13(3), 441-454. Doi:

10.5964/ejop.v13i3.1416

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B., Layton, J.B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. Plos Medicine, 7(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Kitayama S., Markus H. R., Kurokawa M. (2000). Culture, emotion, and well-being: good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition and Emotion, 14(1), 93–124. Doi: 10.1080/026999300379003

Krause, N. (2003). Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. The Journals of Gerontology, 58(3), S160-S170. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.3.S160

Norman, K., Klaus, S. (2020). Veganism, aging and longevity: new insight into old concepts. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 23(2), 145-150. doi:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000625

Pizzino, G., Irrera, N., Cucinotta, M., Pallio, G., Mannino, F., Arcoraci, V., Squadrito, F., Altavilla, D., Bitto, A. (2017). Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2017: 8416763. salgen.it doi: 10.1155/2017/8416763

Ruiu, M., Carta, V., Deiana, C., Fastame, M.C. (2022). Is the Sardinian blue zone the new Shangri-la for mental health? Evidence on depressive symptoms and its correlates in late adult life span. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1315-1322.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-02068-7

Salleh, M.R. (2008). Life event, stress, and illness. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 15(4), 9-18.

Willcox, D.C., Willcox, B.J., Todoriki, H., Curb, J.D., Suzuki, M. (2006). Caloric restriction and human longevity: what we can learn from the Okinawans. Biogerontology, 7, 173-177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-006-9008-z