Study Identifies Link Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Gut Microbiome Composition in a Cohort of Women

Listen to this Article

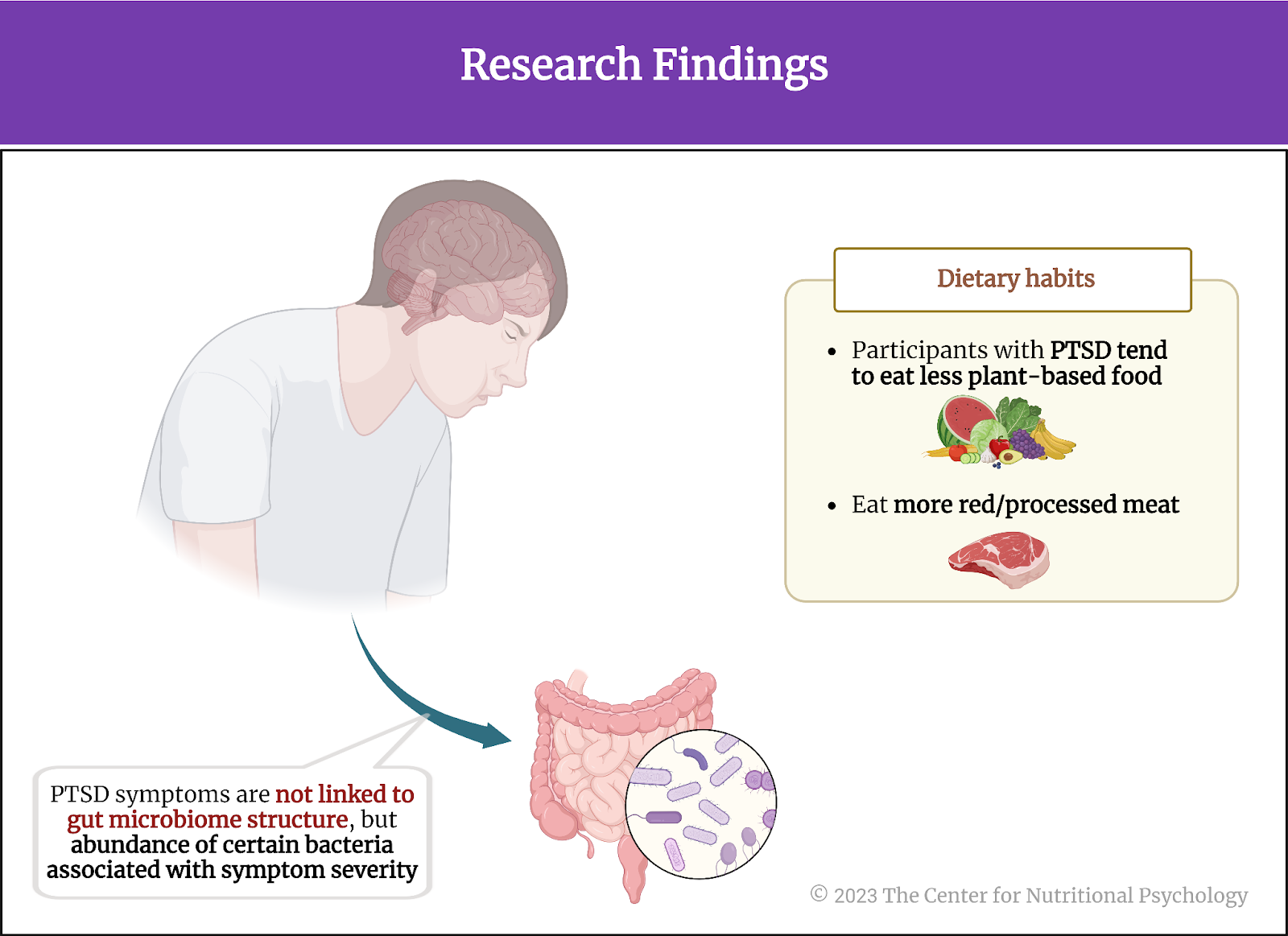

- A study published in Nature Mental Health examined the links between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dietary patterns, and gut microbiome in U.S. nurses

- Results showed that nurses with higher PTSD symptom levels tended to eat less plant-based food and more red/processed meat

- Microbial processes related to the production of pantothenate and coenzyme A can potentially be protective against PTSD

When we are exposed to distressing events or conditions that overwhelm our ability to cope, our body can produce a severe emotional response, and we experience psychological trauma. We feel that we have lost control of events around us. Our ability to integrate these emotional experiences into the story of our lives is reduced. After experiencing psychological trauma, people often start dividing the subjective timeline of their lives into the time before and the time after the traumatic event. Long-lasting psychological and health consequences may often follow (Hamburger et al., 2021). Among other things, the experience of psychological trauma can lead to the development of a serious mental health disorder called post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD.

After experiencing psychological trauma, people often start dividing the subjective timeline of their lives into the time before and after the traumatic event

What is post-traumatic stress disorder?

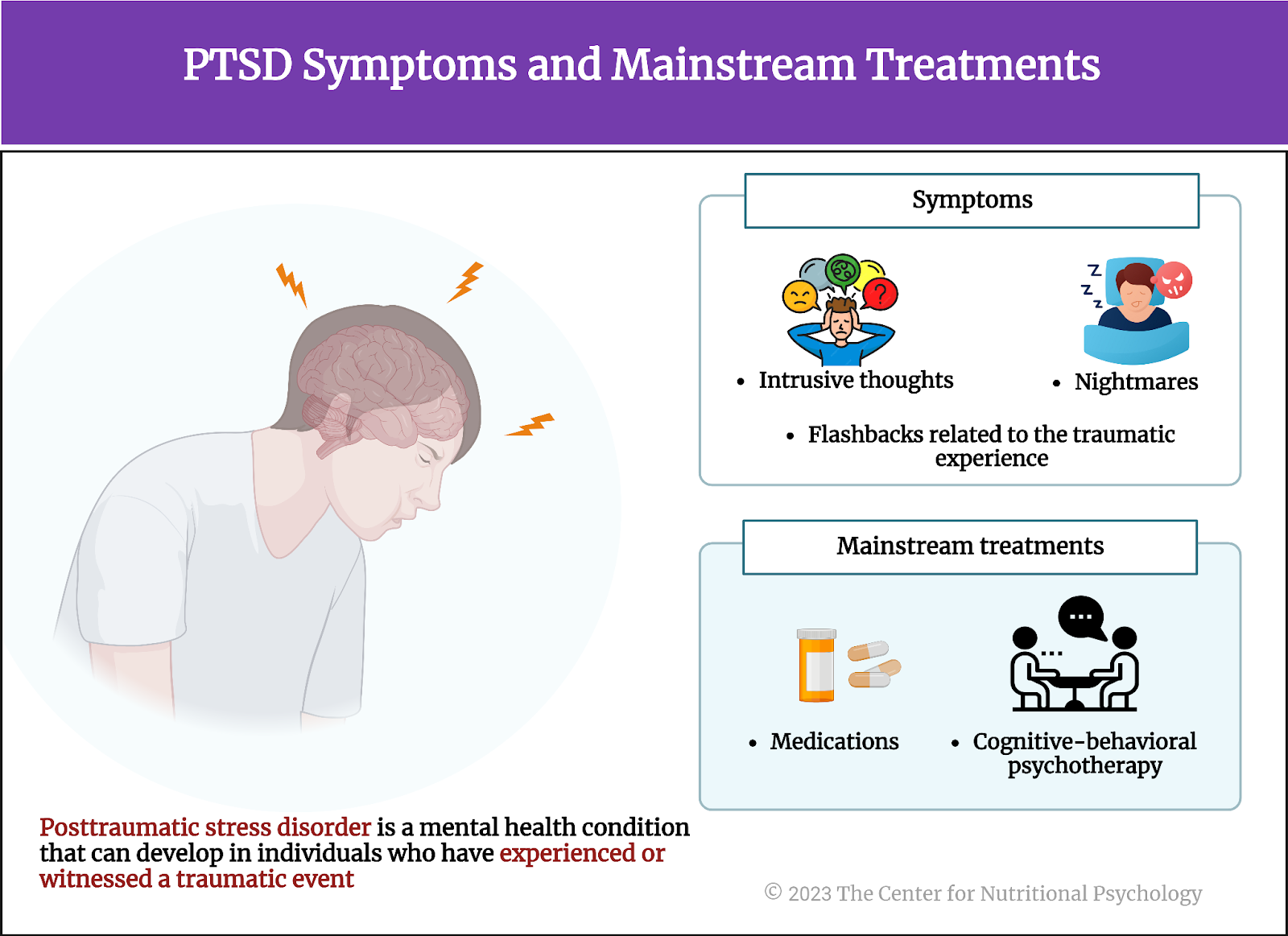

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a mental health condition that can develop in individuals who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event. Symptoms of PTSD include intrusive thoughts, nightmares, and flashbacks related to the traumatic experience, causing significant distress. Individuals with PTSD may actively avoid reminders of the trauma, experience heightened arousal, and have negative changes in mood and cognition.

Mainstream treatments for PTSD include psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, and medications. Studies indicate that these treatments can be effective in reducing PTSD symptoms (see Figure 1). In some individuals, they are very effective (Watts et al., 2013). However, around 20% of patients suffering from PTSD drop out of treatment before symptoms have withdrawn, while up to 60% of individuals undergoing treatment do not respond to it, i.e., experience no reduction of symptoms as a result (Wittmann et al., 2021).

Figure 1. PTSD symptoms and mainstream treatments

For these reasons, researchers are intensely working on new treatment options. They are trying alternative ways to achieve a reduction of symptoms, such as acupuncture (Watts et al., 2013) or psychedelic drugs (Barone et al., 2019). Researchers are also looking at chemicals that could potentially prevent the disorder from forming in the first place if taken immediately after the traumatic event, such as hydrocortisone (Hennessy et al., 2022).

Health impact of PTSD

Individuals suffering from PTSD often suffer from other psychiatric disorders as well. Epidemiological surveys indicate that the vast majority of individuals with PTSD meet the criteria for at least one other disorder, while a substantial percentage have three or more other psychiatric disorders. These most commonly include major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, and anxiety disorders (Brady et al., 2000).

The majority of individuals with PTSD meet the criteria for at least one other disorder, while a substantial percentage have three or more other psychiatric disorders

Individuals with PTSD also have a higher likelihood of various somatic diseases, particularly chronic ones. These include asthma, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain and inflammation, obesity, type 2 diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, and cognitive decline (Ke et al., 2023).

However, researchers are still looking for mechanisms through which this association between PTSD and somatic disorders is achieved. One promising avenue of research is the study of the gut microbiome, the community of organisms living in the human digestive system. The recent discovery of the microbiota-gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication pathway through which gut microorganisms affect processes in the brain and vice versa (Carbia et al., 2023; García-Cabrerizo et al., 2021), has made it even more likely that at least a part of the link between PTSD and somatic disorder includes the gut microbiome.

Researchers are looking for mechanisms connecting PTSD and somatic disorders -with one promising avenue of research being the gut microbiome

The current study

Study author Shanlin Ke and his colleagues hypothesized that gut microbiome might play a role in PTSD. They note that previous studies have already linked the gut microbiome with various other mental health disorders through the microbiota-gut-brain axis (Hedrih, 2023; Leclercq et al., 2020; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019). Additionally, studies show that the gut microbiome influences the brain region involved in learned fear. Fear is a key feature of PTSD. Gut microbiota depends on food intake, while individuals with PTSD tend to be more prone to eating unhealthy foods (Ke et al., 2023).

Previous studies have already linked the gut microbiome with various other mental health disorders through the microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA)

With this in mind, these researchers analyzed data from two studies of female registered nurses in the U.S. in order to systematically examine the associations of trauma exposure and PTSD status with dietary and microbiome data.

The study procedure

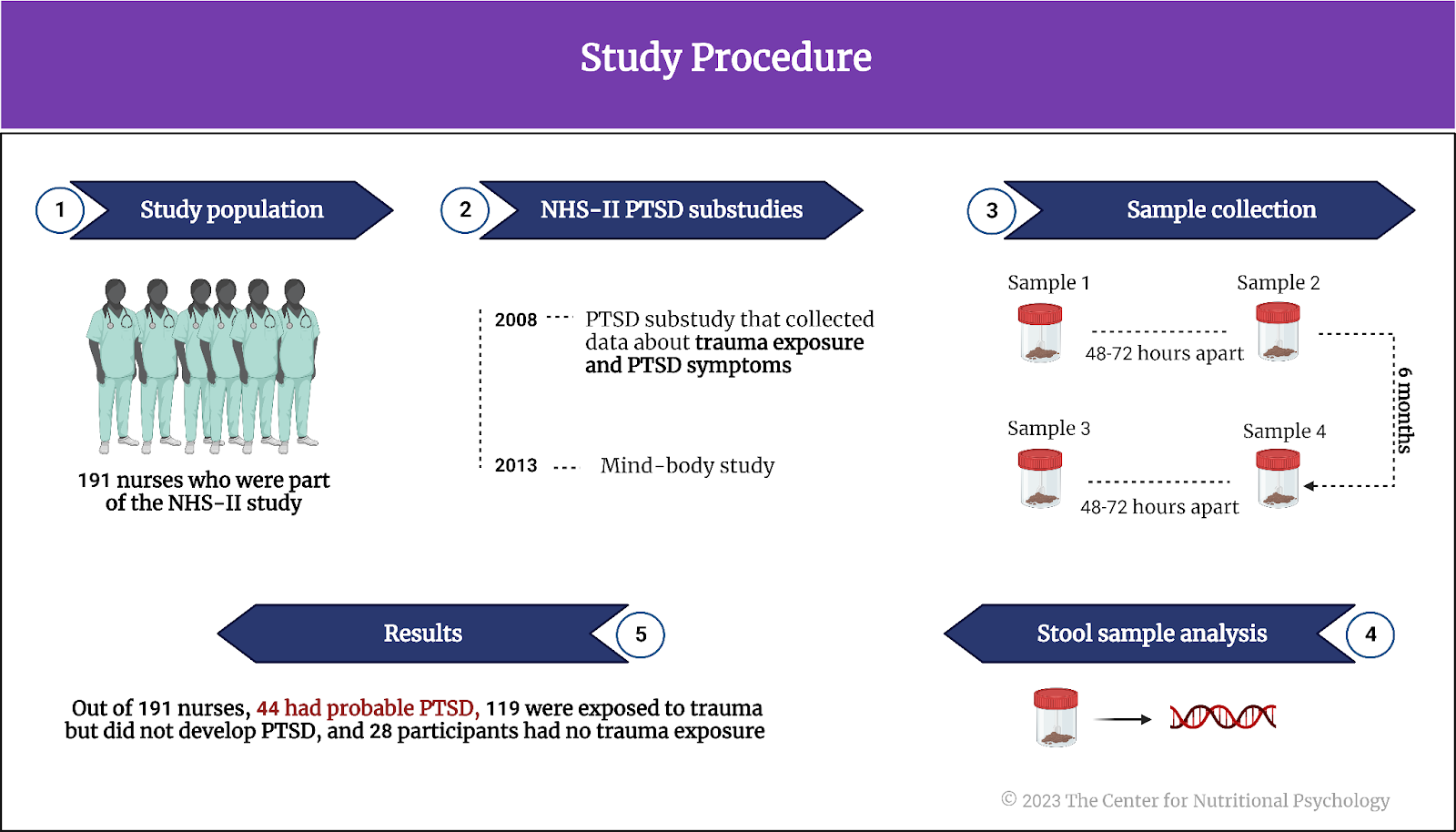

Data came from 191 nurses who were part of the NHS-II study. NHS-II is a large longitudinal study of U.S. women with over 100,000 registered nurses that started in 1989. Nurses whose data were analyzed here participated in two substudies – the 2008 PTSD substudy that collected data about trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms and the 2013 mind-body study that, among other things, collected up to four stool samples. Stool samples were collected 48-72 hours apart. This was followed by a second set of collections six months later. Stool samples were analyzed to make inferences about the composition of the gut microbiome.

Of the nurses included in this study, 44 had probable PTSD, 119 were exposed to trauma but did not develop PTSD, and 28 participants had no trauma exposure (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study Procedure

No association between PTSD and overall microbiome structure

Statistical analyses showed no associations between overall gut microbiota composition and PTSD status. Gut microbiota diversity was also not associated with PTSD.

However, there were associations between various other factors and the overall microbiome structure. Body mass index, depression, and the use of antidepressants were all associated with the overall composition of gut microbiome species.

Childhood trauma experiences and antidepressant use were associated with the relative abundance of species forming different metabolic pathways. The gut microbiome metabolic pathways refer to types of activities within the gastrointestinal tract that specific species of microorganisms perform.

Individuals with PTSD eat less plant-based food and more red/processed meat

Examination of associations between dietary habits and PTSD revealed that individuals with more pronounced PTSD symptoms tend to eat less plant-based foods and more red/processed meats compared to individuals with lower PTSD symptom levels. The diets of these individuals were less healthy overall.

Individuals with more pronounced PTSD symptoms tend to eat less plant-based foods and more red/processed meats compared to individuals with less PTSD symptoms

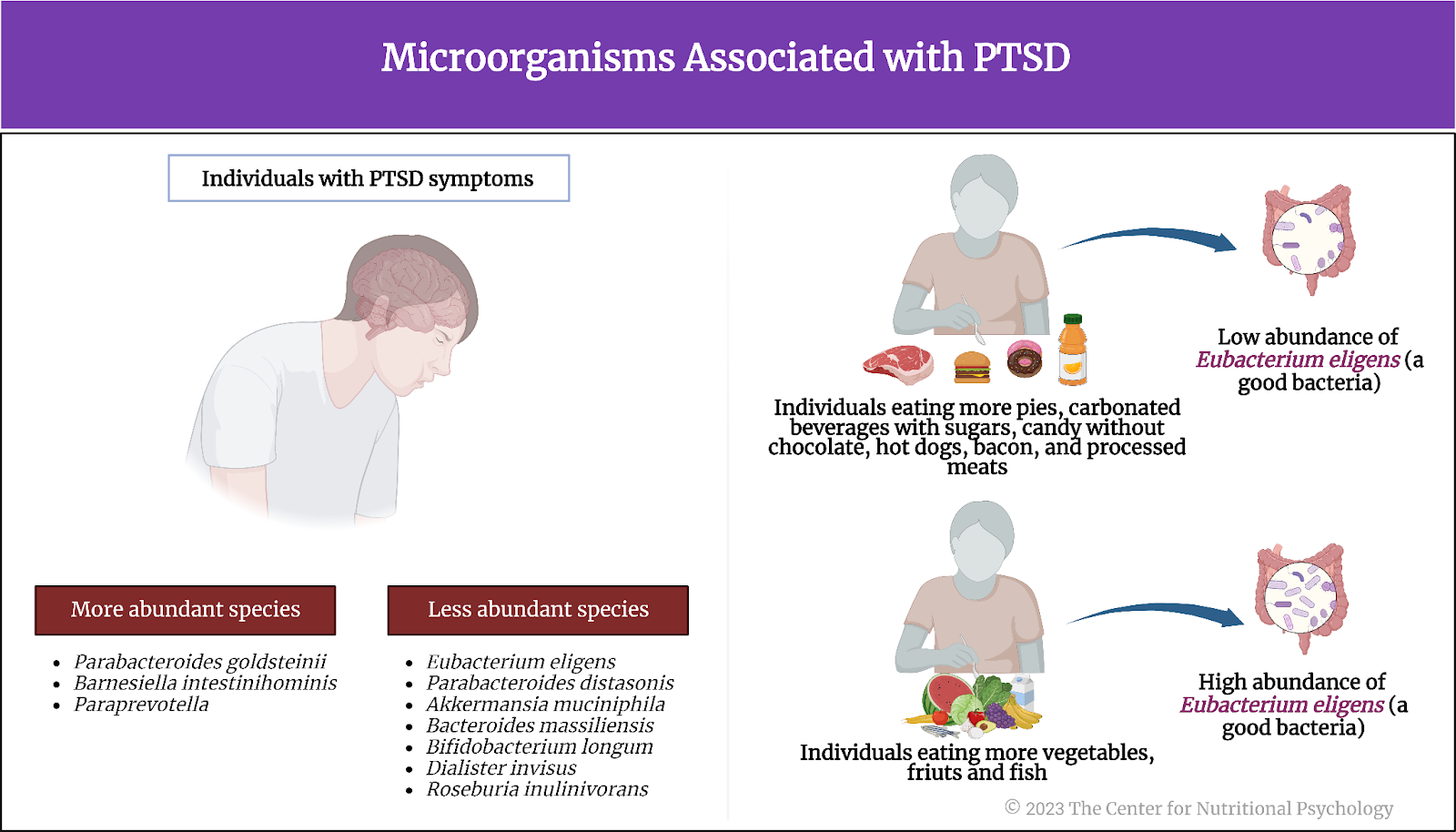

Individuals with PTSD symptoms had lower abundances of Eubacterium eligens

After statistical analyses showed no associations between the overall gut microbiome composition and PTSD, these authors examined associations between PTSD symptoms and the abundance of individual species of bacteria. They looked for species of microorganisms that differed in abundance in individuals with different levels of PTSD symptoms. Three species were clearly more abundant in individuals with more PTSD symptoms – Parabacteroides goldsteinii, Barnesiella intestinihominis, and Paraprevotella unclassified. Seven species with the highest negative association with PTSD symptoms, i.e., species less abundant in individuals with more PTSD symptoms, were also identified (Eubacterium eligens, Parabacteroides distasonis, Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides massiliensis, Bifidobacterium longum, Dialister invisus, and Roseburia inulinivorans). These species play diverse roles in the human digestive system, contributing to functions ranging from fermentation of dietary fibers to protection of the gut lining.

Eubacterium eligens (a good bacteria) was less abundant in individuals eating more pies, carbonated beverages with sugars, candy without chocolate, hot dogs, bacon, and processed meats. It tended to be more abundant in individuals eating more vegetables (for example, raw carrot, spinach/collard greens cooked, and yellow squash), fruits (for example, orange and banana), and fish. The abundance of this bacteria was the most strongly associated with PTSD symptoms of all analyzed microorganisms. Eubacterium eligens in the gut synthesize pantothenate and Coenzyme A (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Microorganisms associated with PTSD

Researchers tested a number of statistical models proposing that specific dietary habits mediate the impact of PTSD symptoms on the abundance of specific species of gut bacteria. These analyses revealed that it is possible that the impact of PTSD symptoms on the abundance of Eubacterium eligens is mediated by the consumption of raw carrots. Similarly, it is possible that Adlercreutzia equolifaciens mediates the link between PTSD symptoms and the intake of dairy-cottage/ricotta cheese.

Conclusion

In summary, the study showed that PTSD symptoms in U.S. nurses are not associated with the overall structure of the gut microbiome, but the abundance of several bacterial species was associated with the severity of PTSD symptoms in spite of this. Additionally, it turned out that participants with PTSD tend to eat less plant-based food and more red/processed meat. Their overall dietary habits tended to be less healthy (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Research findings (Ke et al., 2023)

The study also established statistical links between PTSD symptoms, dietary habits, and bacteria. Future studies could explore the nature of these links in more detail. Potentially, these could lead to the discovery of ways to affect PTSD symptoms through dietary interventions and modifying the abundance of certain species of gut bacteria. However, the feasibility of such an approach is yet to be established.

The paper “Association of probable post-traumatic stress disorder with dietary pattern and gut microbiome in a cohort of women” was authored by Shanlin Ke, Xu-Wen Wang, Andrew Ratanatharathorn, Tianyi Huang, Andrea L. Roberts, Francine Grodstein, Laura D. Kubzansky, Karestan C. Koenen, and Yang-Yu Liu.

Visit the research category within the Nutritional Psychology Research Library on “Diet, Trauma and PTSD” to learn more about the connection between diet and trauma. To access evidence-based continuing education on the connection between the microbiome and mental health, see the CNP Education page.

References

Barone, W., Beck, J., Mitsunaga-Whitten, M., & Perl, P. (2019). Perceived Benefits of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy beyond Symptom Reduction: Qualitative Follow-Up Study of a Clinical Trial for Individuals with Treatment-Resistant PTSD. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 51(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1580805

Brady, K., Killeen, T., Brewerton, T., & Lucerini, S. (2000). Comorbidity of Psychiatric Disorders and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(suppl 7), 22–32.

Carbia, C., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Iannone, F., García-cabrerizo, R., Boscaini, S., Berding, K., Strain, C. R., Clarke, G., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2023). The Microbiome-Gut-Brain axis regulates social cognition & craving in young binge drinkers. EBioMedicine, 89, 104442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104442

García-Cabrerizo, R., Carbia, C., O´Riordan, K. J., Schellekens, H., & Cryan, J. F. (2021). Microbiota-gut-brain axis as a regulator of reward processes. Journal of Neurochemistry, 157(5), 1495–1524. https://doi.org/10.1111/JNC.15284

Hamburger, A., Hancheva, C., & Volkan, V. (Eds.). (2021). Social Trauma – An Interdisciplinary Textbook. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47817-9

Hedrih, V. (2023). Women Consuming Lots of Artificially Sweetened Beverages Might Have a Higher Risk of Depression, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/women-consuming-lots-of-artificially-sweetened-beverages-might-have-a-higher-risk-of-depression-study-finds/

Hennessy, V. E., Troebinger, L., Iskandar, G., Das, R. K., & Kamboj, S. K. (2022). Accelerated forgetting of a trauma-like event in healthy men and women after a single dose of hydrocortisone. Translational Psychiatry, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02126-2

Ke, S., Wang, X.-W., Ratanatharathorn, A., Huang, T., Roberts, A. L., Grodstein, F., Kubzansky, L. D., Koenen, K. C., & Liu, Y.-Y. (2023). Association of probable post-traumatic stress disorder with dietary pattern and gut microbiome in a cohort of women. Nature Mental Health, 1(11), 900–913. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00145-6

Leclercq, S., Le Roy, T., Furgiuele, S., Coste, V., Bindels, L. B., Leyrolle, Q., Neyrinck, A. M., Quoilin, C., Amadieu, C., Petit, G., Dricot, L., Tagliatti, V., Cani, P. D., Verbeke, K., Colet, J. M., Stärkel, P., de Timary, P., & Delzenne, N. M. (2020). Gut Microbiota-Induced Changes in β-Hydroxybutyrate Metabolism Are Linked to Altered Sociability and Depression in Alcohol Use Disorder. Cell Reports, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CELREP.2020.108238

Valles-Colomer, M., Falony, G., Darzi, Y., Tigchelaar, E. F., Wang, J., Tito, R. Y., Schiweck, C., Kurilshikov, A., Joossens, M., Wijmenga, C., Claes, S., Van Oudenhove, L., Zhernakova, A., Vieira-Silva, S., & Raes, J. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology, 4(4), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x

Watts, B. V., Schnurr, P. P., Mayo, L., Young-Xu, Y., Weeks, W. B., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6). https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r08225

Wittmann, L., Muller, J., Morina, N., Maercker, A., & Schnyder, U. (2021). Predicting Treatment Response in Psychotherapy for Postraumatic Stress Disorder: a Pilot Study. Psihologija, 54(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI190905007W

Leave a comment