Restrained Eating Leads to Hunger and Food Craving

Editor’s Note: Amidst the intricate interplay of factors and mechanisms that underlie the complex phenomenon of overeating, it becomes apparent that balance holds the key. This pivotal equilibrium finds its roots through the lens of nutritional psychology (NP), where its examination reveals profound insights. The increased availability of hyper-palatable foods holds sway over our brain’s dietary mechanisms, along with the intricate interactions within the microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) (de Macedo et al., 2016; Demeke et al., 2023; Gupta et al., 2020). Among the factors shaping today’s modern dietary landscape, the escalating prevalence of food insecurity and the psychophysiological repercussions stemming from heightened levels of environmental and social stress take center stage (Cortés-García et al., 2022; Hazzard, 2023). Furthermore, many of these factors and mechanisms incline us to steer our dietary preferences towards a hedonistic approach to eating, characterized by the pursuit of pleasure and rewards rather than the fundamental homeostatic eating required for energy maintenance and regulation (Lutter et al., 2009). This inclination can catalyze adaptive dietary behaviors, including the engagement of tactics like ‘restrictive’ methods or reliance on the “force of will” (i.e., willpower) to counteract or prevent episodes of overeating and obesity (Adams et al., 2019). Consequently, the combined impact of these dynamics and the mechanisms governing heightened hedonistic eating can foster a cycle wherein feelings of hunger, cravings, and the propensity to overindulge intensify when one’s willpower depletes, eventually leading to a destructive pattern of restrained eating.

Study Overview

A study in Israel followed changes in food craving, restrained eating, hunger, and negative emotions within a representative sample of the population over a span of 10 days. The findings revealed that restrained eating is the central link between food-related sensations and negative emotions. The participants who engaged in restrained eating exhibited heightened food cravings and increased hunger at later times. Notably, stress emerged as a pivotal factor in the correlation between eating behaviors and negative emotional states, as outlined by Dicker-Oren and colleagues (2022). The study was published in Appetite.

Introduction

Food is one of the most fundamental needs of all living organisms. In the classical hierarchy of human needs proposed in the mid-20th century by Abraham Maslov, food is one of the primary needs that must be satisfied if other, higher-level needs are to be activated (Lester, 2013). This is why humans (and most other organisms) have evolved several psychological and behavioral mechanisms to ensure that securing enough food is given top priority.

Humans have evolved psychological and behavioral mechanisms to ensure that securing enough food is given top priority

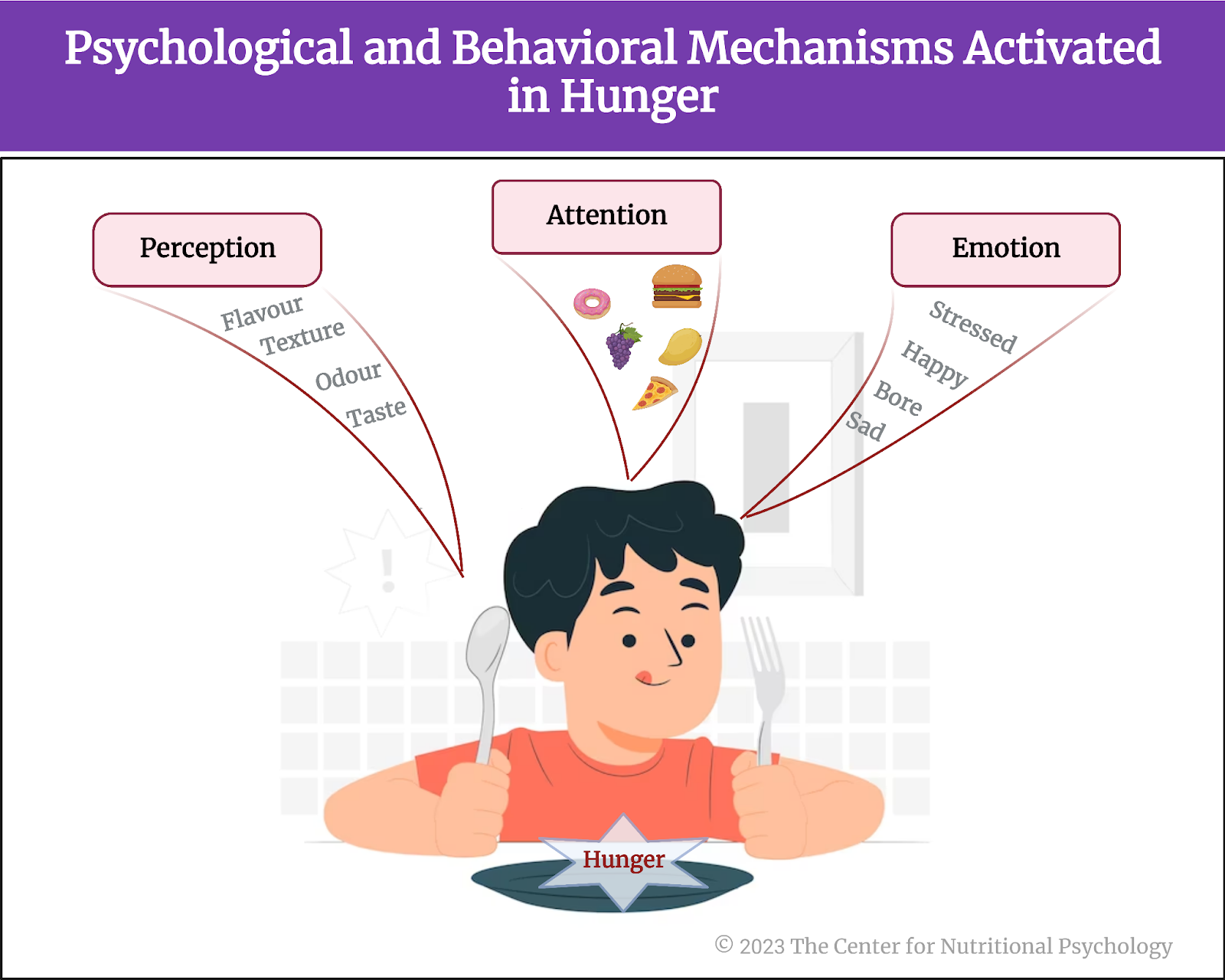

These mechanisms induce changes to perception, attention, emotions, and various physiological parameters when we are hungry (Swami et al., 2022) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Psychological and behavioral mechanisms activated in hunger (Swami et al., 2022)

These mechanisms aim to focus us on food and prepare us for food intake, allowing us to survive and flourish for millennia of human existence. However, around the mid-20th century, a crucial change in the human dietary landscape happened – industrially processed foods became widely available and cheap. While the widespread availability of high-calorie and addictive processed foods has addressed food insecurity in many parts of the world, it has also given rise to a new challenge — obesity.

The obesity pandemic

Obesity is a medical condition characterized by excessive body fat accumulation, negatively affecting host health and well-being. The share of obese individuals in the population has been on the rise in recent decades in most world countries (Wong et al., 2022), reaching levels where many are talking about a global obesity pandemic.

While it is fairly obvious that excessive intake of food is a necessary component in the development of obesity, this excessive intake of food is caused by a combination of various biological, psychological, and physiological factors (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2015). Among these, emotions and food-related sensations are thought to be important.

While it is fairly obvious that excessive intake of food is a necessary component in the development of obesity, this excessive intake of food is caused by a combination of various biological, psychological, and physiological factors

Food craving and hunger

Food craving is a strong desire to consume specific foods, such as chocolate or potato chips (van Kleef et al., 2013). It differs from hunger by its specificity and intensity. People can crave food even when they are not hungry (Reichenberger et al., 2018). On the other hand, the sensation of hunger makes one motivated to eat, but not necessarily a specific type of food.

Food craving is a strong desire to consume specific foods or food types. It differs from hunger by its specificity and intensity.

Food craving may be a response to physiological deficiencies or disturbances in the body, but they may also be initiated through psychological mechanisms without deficiencies of nutrients (Weingarten & Elston, 1990). Food cravings are considered to be one of the main factors of overeating.

Food craving may be a response to physiological deficiencies or disturbances in the body, but they may also be initiated through psychological mechanisms without deficiencies in nutrients

When individuals notice they are gaining excessive weight or if they are worried they may be eating too much, many will try to limit their food intake consciously. Rather than rely on the sensation of satiety to signal that they have eaten enough, or if the over-consumption of hyperpalatable foods distorts these cues, these individuals may consciously decide to limit how much food they will eat. The amount will often be such that the person still feels hungry after eating it.

This type of behavior is referred to in science as restrained eating. People who engage in restrained eating often set rules or restrictions on what and how much they can eat, and they may closely monitor their calorie intake. This is usually done in an effort to achieve a specific body image or weight goal. However, restrained eating can sometimes lead to disordered eating patterns and psychological distress (Dicker-Oren et al., 2022).

The current study

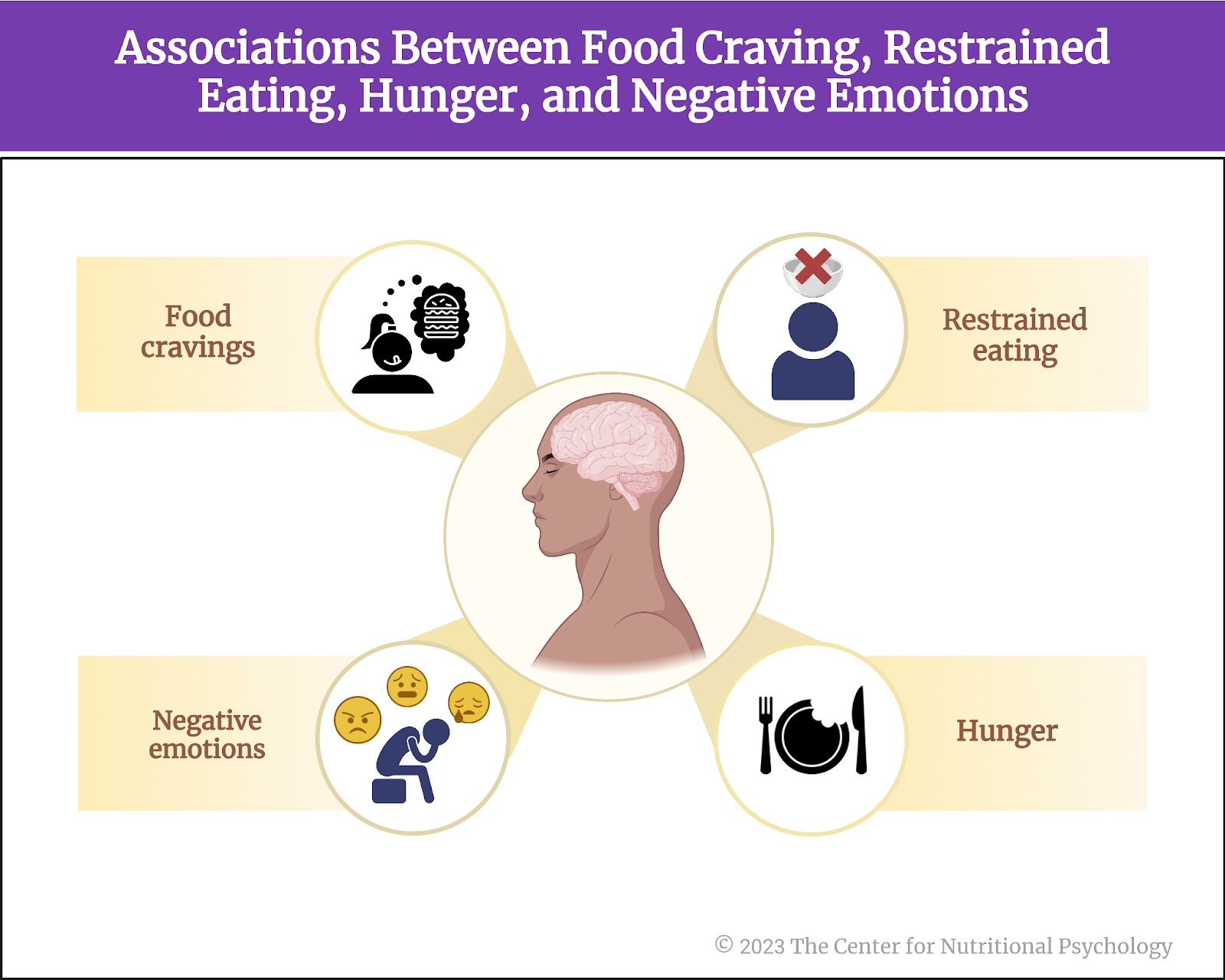

Study author S.D. Dicker-Oren and colleagues aimed to examine the dynamic associations between food craving, restrained eating, hunger, and negative emotions. They wanted to know how these factors vary in the same individual over time. These researchers were particularly interested in determining whether negative emotions associated with food craving, restrained eating, and hunger differed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The study objective examined associations between food craving, restrained eating, hunger, and negative emotions.

They applied an analytic technique called network analysis to map the network of links between these factors and identify those that are central that can best predict others. The study authors also wanted to know which factors were most strongly associated with food cravings simultaneously and in subsequent assessments. They conducted a study using ecological momentary assessment.

Ecological momentary assessment

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) is a research method to gather real-time data about individuals’ behaviors, thoughts, and emotions in their natural environments. It involves repeatedly sampling participants’ experiences over time, often through mobile devices like smartphones, to capture their moment-to-moment fluctuations and responses to various stimuli. Ecological momentary assessment provides valuable insights into how individuals’ psychological states and behaviors vary daily.

In this study, researchers wanted to observe whether food craving, hunger, restrained eating, and related emotions change within the same person. This procedure allowed them to observe, for example, what other sensations or emotions appear when a person experiences a craving for a certain type of food or whether participants tend to experience some specific emotions at the same time when they experience hunger or when they intentionally try to reduce their food intake, even though they still feel hungry.

Researchers wanted to observe whether food craving, hunger, restrained eating, and related emotions change within the same person

The procedure

Participants were 123 individuals from the general population of Israel. The study authors recruited them using social media posts and advertisements. To be included in the study, participants needed to be at least 18 years of age, with no severe psychiatric illness, not be underweight, have no eating disorders, and not have undergone obesity-related surgery. Female participants could not be pregnant or breastfeeding at the time of the study.

In the scope of the ecological momentary assessment procedure, participants answered questionnaires in the form of online surveys on the Qualtrics platform three times per day – in the morning, afternoon, and evening, over the course of 10 days. For each survey, the data collection software sent them a personal email message with the link to the survey and a WhatsApp notification on their smartphone. If a respondent missed four surveys, researchers would call him/her by phone to encourage him/her to continue participating in the study.

Participants answered questionnaires in the form of online surveys three times per day – in the morning, afternoon, and evening, over the course of 10 days

The surveys

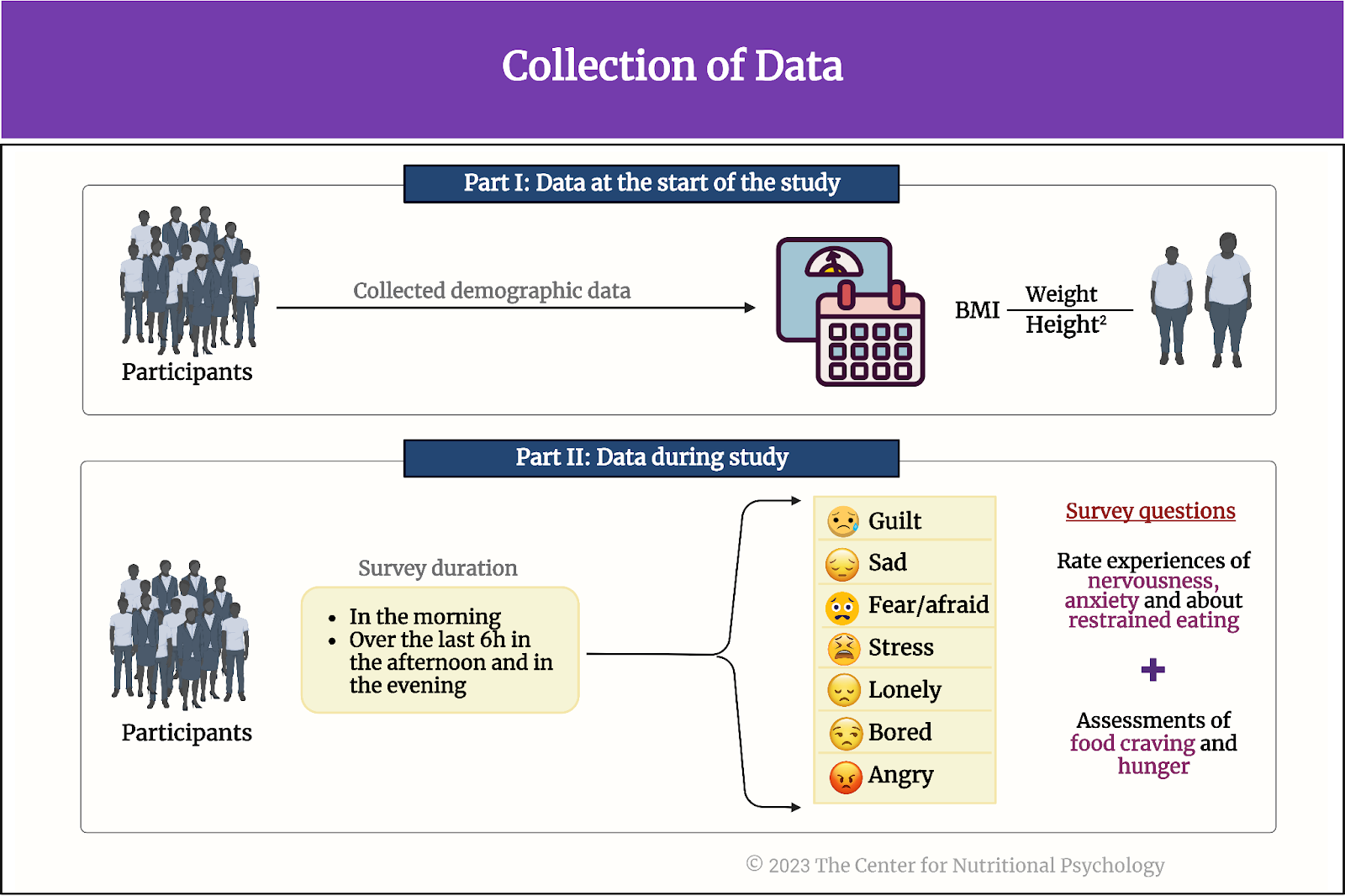

At the start of the study, participants completed the baseline questionnaire. This questionnaire contained questions about various demographic characteristics of participants and about their weight and height. The study authors combined weight and height data to calculate body mass index values for each participant.

The questionnaires participants completed in the scope of the ecological momentary assessment asked them to indicate the extent to which they experienced each of the sensations and emotions from a list “since you woke up,” in the morning version of the questionnaire, or “over the last six hours” in the afternoon and evening versions. The questions were about experiencing seven different negative emotions – guilt, sadness, fear/ being afraid, stress, loneliness, boredom, and anger. It also asked about experiences of nervousness and anxiety and about restrained eating (“Did you deliberately try to limit the amount of food you eat?”) (see Figure 3). Additionally, participants completed assessments of food craving and hunger (“intense desire to eat” and “hunger” subscales from the Food Cravings Questionnaire-state, FCQ-S) in the scope of these surveys.

Figure 3. Sensations and emotions and restrained eating, assessments of food craving and hunger

Observed factors showed a degree of stability over time

Most of the factors measured tended to show certain stability over time. In later surveys, people who reported higher levels of negative emotions, hunger, craving, or restrained eating at one time point were also more likely to report these emotions and sensations.

Participants who reported consciously limiting their food intake were more likely to be hungry and crave food later

Individuals who reported restrained eating and hunger earlier were more likely to report food craving at the subsequent time. Individuals who reported restrained eating at one time were likelier to report being hungry later. Participants who reported sadness were likely to report loneliness and anger later. They were also more likely to report feeling stressed, afraid, and angry at later time points. When participants reported feeling stressed at one time, they were more likely to report craving food the next time.

When participants reported feeling stressed at one time, they were more likely to report craving food the next time

Certain participants experienced a frequent interplay of restrained eating, hunger, and food craving

Across all time points/surveys, participants who more often reported food craving were also more likely to report experiencing hunger and practicing restrained eating. Stress was the central emotion – participants who more often reported feeling stressed were more likely to report experiencing all other negative emotions as well. However, researchers found no association between mean levels of hunger, food craving, or restrained eating and average levels of negative emotions.

Individuals practiced restrained eating less when they were angry. They tended to crave food more when they were feeling bored.

Conclusion

The study revealed one piece of insight into the complex interplay between food-related sensations, negative emotions, and restrained eating. Restrained eating seemed to drive hunger and food craving. Individuals who exerted effort to consciously limit their food intake also more often experienced hunger and food craving. These two experiences often followed restrained eating. Hunger appeared to trigger food craving, but food craving did not seem to predict any overeating-related variables at later times (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Study findings

The study results have important implications for beginning to understand some of the psychological dynamics of eating disorders and for planning interventions. The finding that restrained eating, which in itself represents an attempt by an individual to prevent excessive food intake (and perhaps the upregulation in brain and gut reward-based systems in the body), can, in this instance, actually have a reverse effect in the long run (by increased hunger and food craving) indicating that interventions aiming to reduce restrained eating might paradoxically have a positive effect on regulating food intake. The finding that stress can drive food craving indicates that it might also be useful for eating disorder interventions to address stress.

The paper “The dynamic network associations of food craving, restrained eating, hunger and negative emotions” was authored by S.D. Dicker-Oren, M. Gelkopf, and T. Greene.

More about dietary intake behavior, hedonic eating, and reward and gut-based mechanisms can be found in NP 110: Introduction to Nutritional Psychology Methods, and NP 120 Part I: Microbes in our Gut: An Evolutionary Journey into the World of the Microbiota Gut-Brain Axis and the DMHR and NP 120 Part II: Gut-Brain Diet-Mental Health Connection: Exploring the Role of Microbiota from Neurodevelopment to Neurodegeneration.

References

Adams, R. C., Chambers, C. D., & Lawrence, N. S. (2019). Do restrained eaters show increased BMI, food craving and disinhibited eating? A comparison of the restraint scale and the restrained eating scale of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Royal Society open science, 6(6), 190174. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190174

Cortés-García, L., Rodríguez-Cano, R., & von Soest, T. (2022). Prospective associations between loneliness and disordered eating from early adolescence to adulthood. The International journal of eating disorders, 55(12), 1678–1689. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23793

de Macedo, I. C., de Freitas, J. S., & da Silva Torres, I. L. (2016). The influence of palatable diets in reward system activation: A mini-review. Advances in pharmacological sciences, 2016, 7238679. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7238679

Demeke, S., Rohde, K., Chollet-Hinton, L., Sutton, C., Kong, K. L., & Fazzino, T. L. (2023). Change in hyper-palatable food availability in the US food system over 30 years: 1988-2018. Public health nutrition, 26(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022001227

Dicker-Oren, S. D., Gelkopf, M., & Greene, T. (2022). The dynamic network associations of food craving, restrained eating, hunger and negative emotions. Appetite, 175(March), 106019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106019

Gupta, A. R., Osadchiy, V., & Mayer, E. A. (2020). Brain–gut–microbiome interactions in obesity and food addiction. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 17(11), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0341-5

Hazzard, V. M., Loth, K. A., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Engel, S. G., Larson, N., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2023). Relative food abundance predicts greater binge-eating symptoms in subsequent hours among young adults experiencing food insecurity: Support for the “feast-or-famine” cycle hypothesis from an ecological momentary assessment study. Appetite, 180, 106316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106316

Lester, D. (2013). Measuring Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Psychological Reports, 113(1), 1027–1029. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.20.PR0.113x16z1

Lutter, M., & Nestler, E. J. (2009). Homeostatic and hedonic signals interact in the regulation of food intake. The Journal of nutrition, 139(3), 629–632. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.108.097618

Reichenberger, J., Richard, A., Smyth, J. M., Fischer, D., Pollatos, O., & Blechert, J. (2018). It’s craving time: Time of day effects on momentary hunger and food craving in daily life. Nutrition, 55-56, 15-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.03.048

Swami, V., Hochstöger, S., Kargl, E., & Stieger, S. (2022). Hangry in the field: An experience sampling study on the impact of hunger on anger, irritability, and affect. PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0269629. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0269629

Thanarajah, S. E., Difeliceantonio, A. G., Albus, K., Br, J. C., Tittgemeyer, M., Small, D. M., Thanarajah, S. E., Difeliceantonio, A. G., Albus, K., Kuzmanovic, B., & Rigoux, L. (2023). Habitual daily intake of a sweet and fatty snack modulates reward processing in humans Clinical and Translational Report Habitual daily intake of a sweet and fatty snack modulates reward processing in humans. Cell Metabolism, 35, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.015

Ulrich-Lai, Y. M., Fulton, S., Wilson, M., Petrovich, G., & Rinaman, L. (2015). Stress exposure, food intake and emotional state. Stress, 18(4), 381–399.

van Kleef, E., Shimizu, M., & Wansink, B. (2013). Just a bite: Considerably smaller snack portions satisfy delayed hunger and craving. Food Quality and Preference, 27(1), 96-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.06.008

Weingarten, H. P., & Elston, D. (1990). The phenomenology of food cravings. Appetite, 15(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(90)90023-2

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005

Leave a comment