Food and Mood: Is the Concept of ‘Hangry’ Real?

Editor’s Note: Since the dawn of history, people have known all too well that there is a link between hunger and mood. Sayings like “A hungry man is an angry man,” “The belly rules the mind,” “When the stomach is full, the heart is glad,” or “A hungry stomach has no ears” are well-known throughout the world. These sayings all link hunger with negative states, like anger or a preoccupation with finding food, while associating a “full stomach” with positive emotions and behaviors. They also imply that hunger and satiety exert a very powerful influence on one’s behavior.

A recent study conducted in Austria used the method of experience sampling to examine the links between hunger and mood. Researchers asked participants to report their hunger and mood five times per day. Results showed that participants reported greater anger, irritability, and decreased pleasure when hungry (Swami et al., 2022). The study was published in Plos One.

Hunger and satiety exert a very powerful influence on one’s behavior.

Nutritional psychology, as explored by The Center for Nutritional Psychology, focuses on the links between diet, psychological states, and mental health. While the significance of this research topic is widely acknowledged, it remains a relatively new field of study, with crucial findings likely to emerge in the future.

What is hunger?

From a physiological point of view, hunger is a complex biological process that primarily revolves around regulating blood glucose levels and releasing hormones that control appetite and satiety. When we eat food, our bodies break down carbohydrates into glucose, which is the primary energy source for cells. As we go without food, our blood glucose levels gradually decline.

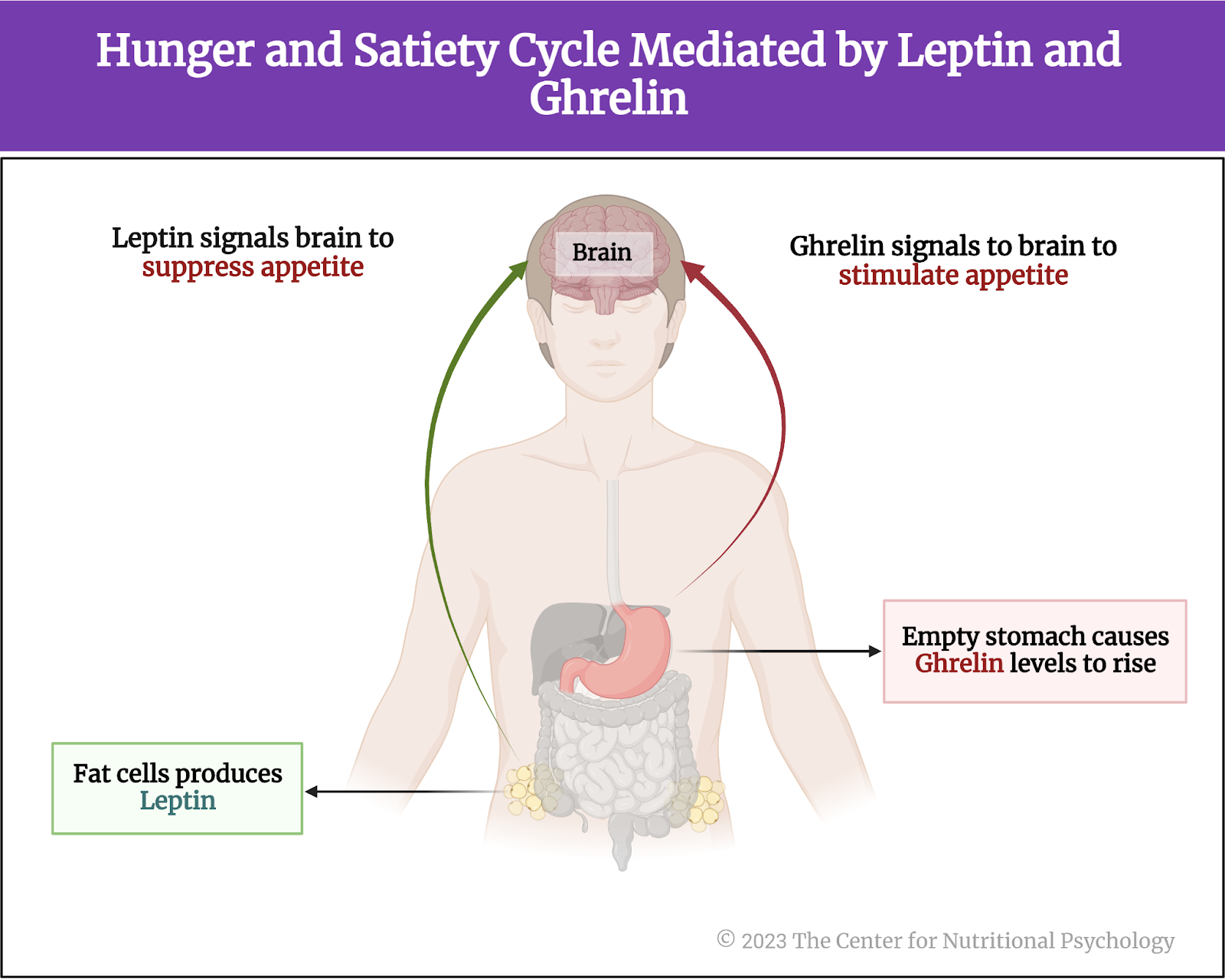

The two key hormones involved in hunger regulation are ghrelin and leptin. Ghrelin, produced by the stomach, signals the brain to stimulate appetite when the stomach is empty. Before meals, ghrelin levels increase, and they decrease after eating. Leptin functions as an appetite suppressor and is produced by fat cells, so when body fat decreases, leptin levels drop (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Two key hormones involved in hunger regulation are Ghrelin and Leptin

Finally, the brain integrates the input received from hormones and sensory organs (e.g., sight or smell of food) to produce the feeling of hunger or satiety. This integration of signals happens in the hypothalamus region of the brain.

The sensation of hunger

Apart from being the result of a complex physiological process, hunger is also a subjective sensation. This sensation serves to motivate the individual to seek food and ingest it. In turn, this ensures that the nutritional needs of the organism are met (McKiernan et al., 2008). When an individual feels hungry, they become more sensitive to stimuli associated with food (e.g., Lazarus et al., 1953). Individuals will pay increased attention to food items and things they have learned to associate with food (e.g., logos of restaurants or food brands, places and people they have learned to associate with food, etc.).

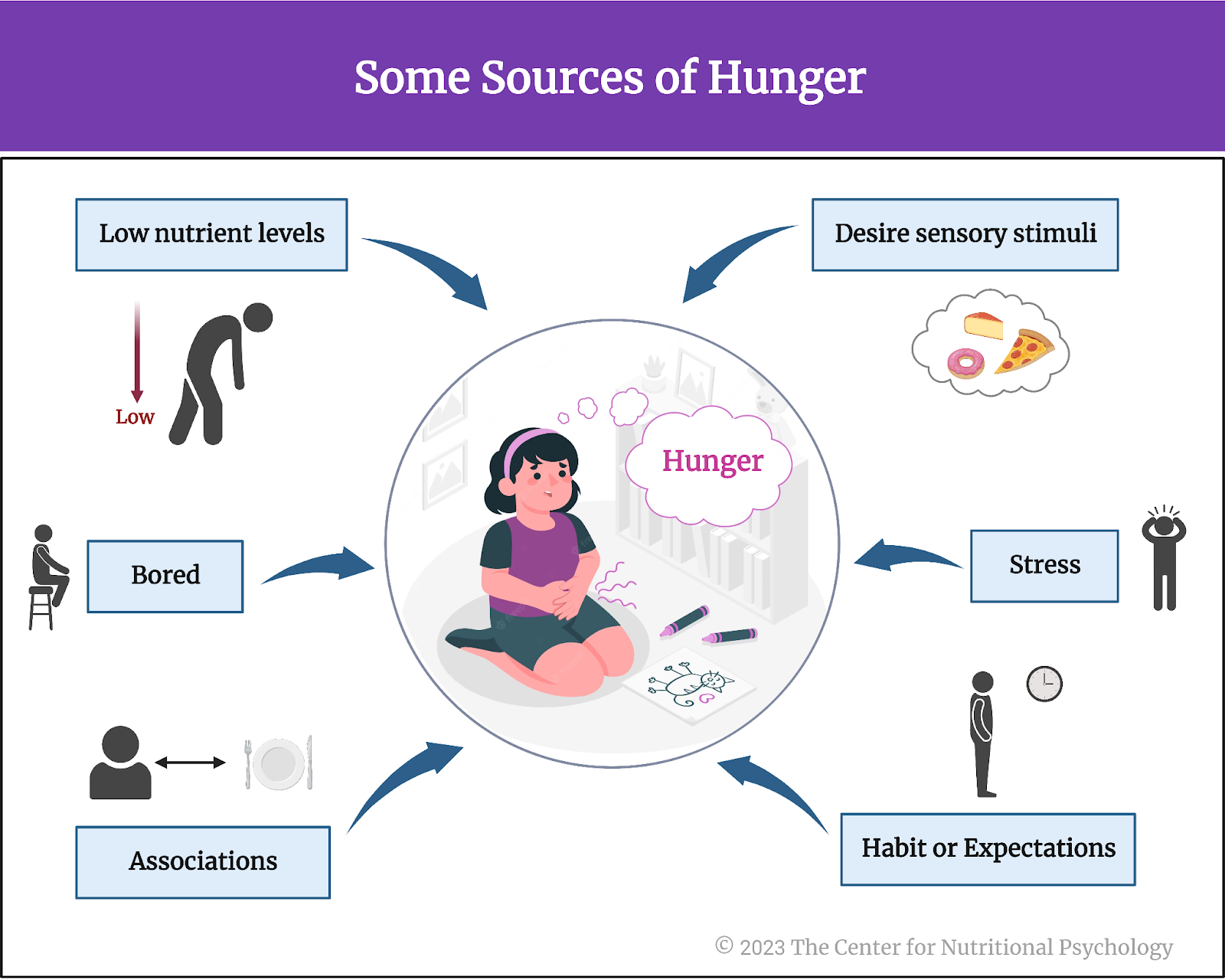

However, decreased levels of nutrients in the body are not the only thing that can lead to the sensation of hunger. Studies show that humans and other species of animals can eat when bored, desire sensory stimulation (McKiernan et al., 2008), or are under stress (Levine & Morley, 1981). They also learn to expect food at certain times or at certain places. Studies indicate that under regular circumstances, human daily rhythms of biological processes (circadian rhythms) are synchronized with a pattern of three meals per day. However, the body can also adapt and learn to expect meals at different times of the day. This expectation can trigger hunger at a particular time and various physiological processes preparing the body for food intake (Isherwood et al., 2023) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Some sources of hunger

Being “hangry” – hungry and angry

Hunger affects the behavior of both humans and animals. Observations of non-human animals show that food deprivation increases their motivation to engage in escalated and persistent aggression to acquire food. It is well-known among keepers of various animals that the animals are the most dangerous when hungry.

Studies in humans link the sensation of hunger with feelings of restlessness, nervousness, irritability, and behavioral difficulties in children. Low blood glucose levels, known to trigger the sensation of hunger, are associated with increased impulsivity, anger, and aggression (Swami et al., 2022). Studies applying the concept of ego depletion suggest that the human capacity for self-regulation and active volition is limited (Baumeister et al., 1998) and that when one is hungry, negative, high-arousal emotions are more likely to occur. This is because individuals may struggle to exercise self-regulation and self-control when their blood glucose is low (Swami et al., 2022).

Studies in humans link the sensation of hunger with feelings of restlessness, nervousness, irritability, and behavioral difficulties in children.

These findings and casual observations have given rise to the term “hangry.” A combination of “hungry” and “angry,” hangry signifies a state in which one experiences both hunger and anger due to hunger.

Coined from hungry and angry, the term “hangry” indicates a state in which one is hungry but is also angry because of hunger.

The current study

Viren Swami, the study author, and his colleagues aimed to investigate the state of being “hangry” in a natural setting more systematically.

They wanted to know the extent to which daily experiences of hunger are associated with negative emotional outcomes. They reasoned that if the sensation of hunger is indeed linked to anger and other negative emotions, this must be the case in everyday life and not only in laboratory experiments.

To examine this link, they conducted an experience sampling study in which a group of study participants reported on their daily experiences of hunger and anger over a 3-week period. Understanding that anger might not be the only emotion connected to hunger, the study authors asked participants to report on irritability, pleasure, and arousal. They expected that hunger would be associated with greater anger, irritability, and arousal but lower feelings of pleasure.

What is experience sampling?

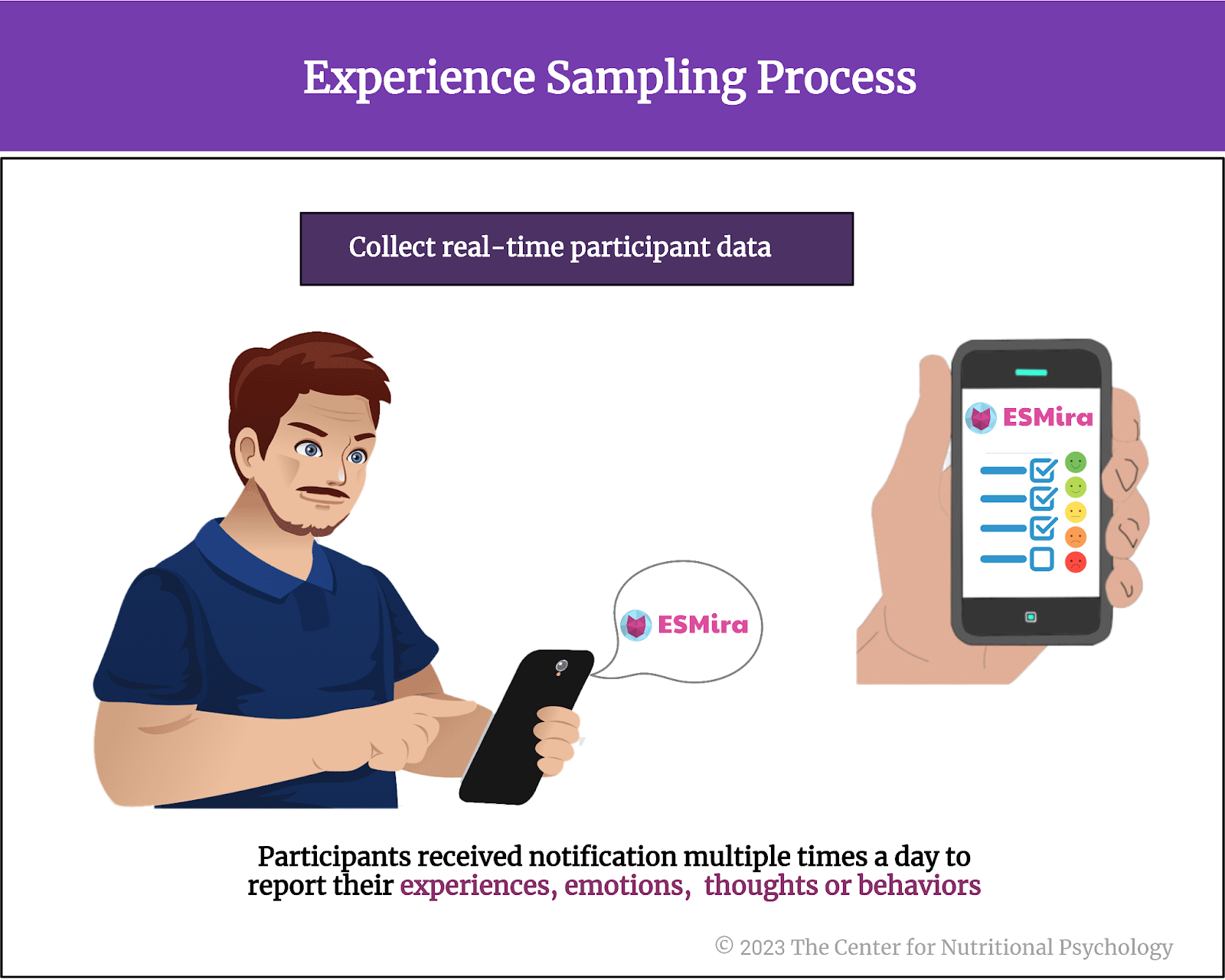

Experience sampling (Figure 3), or ecological momentary assessment, involves collecting real-time participant data throughout their daily lives. Participants are prompted multiple times daily to report on their experiences, emotions, behaviors, or thoughts using electronic devices such as smartphones or specialized wearable devices. This method gives researchers insights into individuals’ subjective experiences in their natural settings. This approach minimizes issues related to recalling events after much time has passed, a common problem encountered in traditional research methods relying on recalling past events. Experience sampling allows for a more nuanced understanding of how various factors fluctuate over time and under different circumstances.

Figure 3. Experience sampling process

The procedure

The study initially involved 121 participants; however, it required them to respond to surveys five times daily, every day, for three weeks, resulting in a total of 105 surveys to be completed by each participant. This workload proved overwhelming for many, with only 39 participants successfully completing all 105 surveys. Seventy-six participants managed to complete at least one survey per day.

Participants were, on average, 30 years old. Their ages ranged between 18 and 60 years. 69% were from Austria, followed by Germany (20%), Switzerland, and other countries. The vast majority of the participants were women (81%). 44% lived alone, 19% were married, and 36% were in a relationship. They had an average of 14 years of education.

Daily surveys

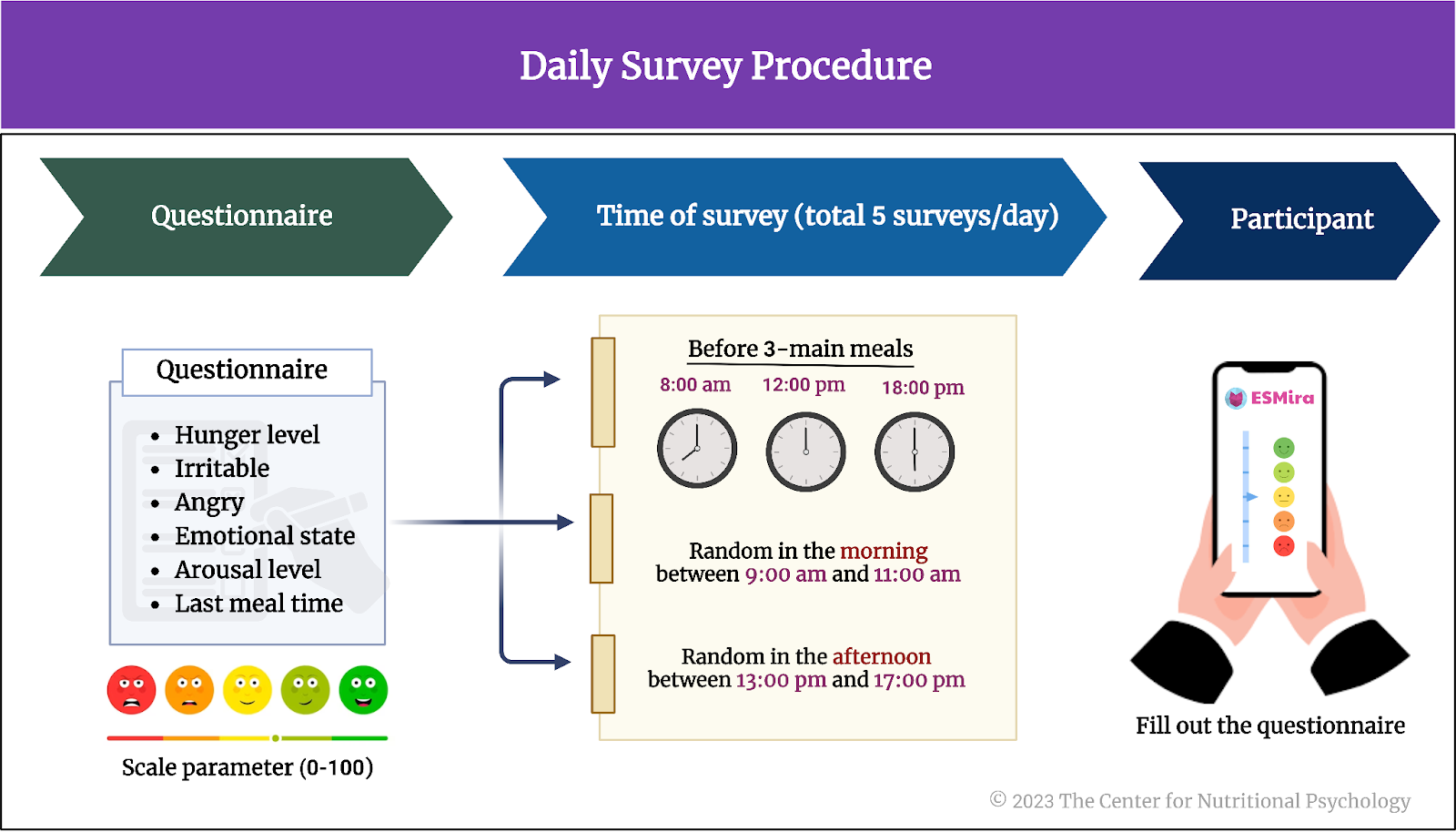

In the survey, participants indicated on a scale of 0 to 100 how hungry they were (“How hungry are you at the moment?”), their irritability (“How irritable do you feel at the moment?”), and how angry they felt at that moment. In addition, they rated their emotional state (“How pleasant do you find your current state?”), and arousal level (“What is your current arousal level?”). They also reported the time since their last meal (“When was your last meal? [______ hours ago]”.

Participants completed the surveys using their smartphones through the ESMira software package. After installing ESMira and registering for participation in the study, participants provided their demographic data. Of the five daily surveys, study authors set three to be at fixed time points during the day, before the three main meals – at 8:00, 12:00, and 18:00. At these time points, participants received an in-app notification to complete the survey. The remaining two surveys were random, one between 9:00 and 11:00 in the morning and the other between 13:00 and 17:00 (in the afternoon) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Daily survey procedure

Other measures

After the three-week period of the study, participants completed the final questionnaire, in which they provided their demographic data once again. It also contained assessments of four aspects of dietary behavior – restrictive eating (e.g., “I consciously eat less so as not to gain weight”), two aspects of emotionally-induced eating behavior, with clear emotions (e.g., “When I am irritated, I have the desire to eat”) and unclear emotions (e.g., “I always want to eat something when I have nothing to do”), and externally determined eating behavior (e.g., “I eat more than usual when I see others eating”).

The final questionnaire also contained assessments of dispositional anger (the Anger subscale from the Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire, BPAQ) and eating motivation (the Eating Motivation Survey consists of the question “Why do you eat what you eat?” followed by 15 different motivations that the participant has to rate).

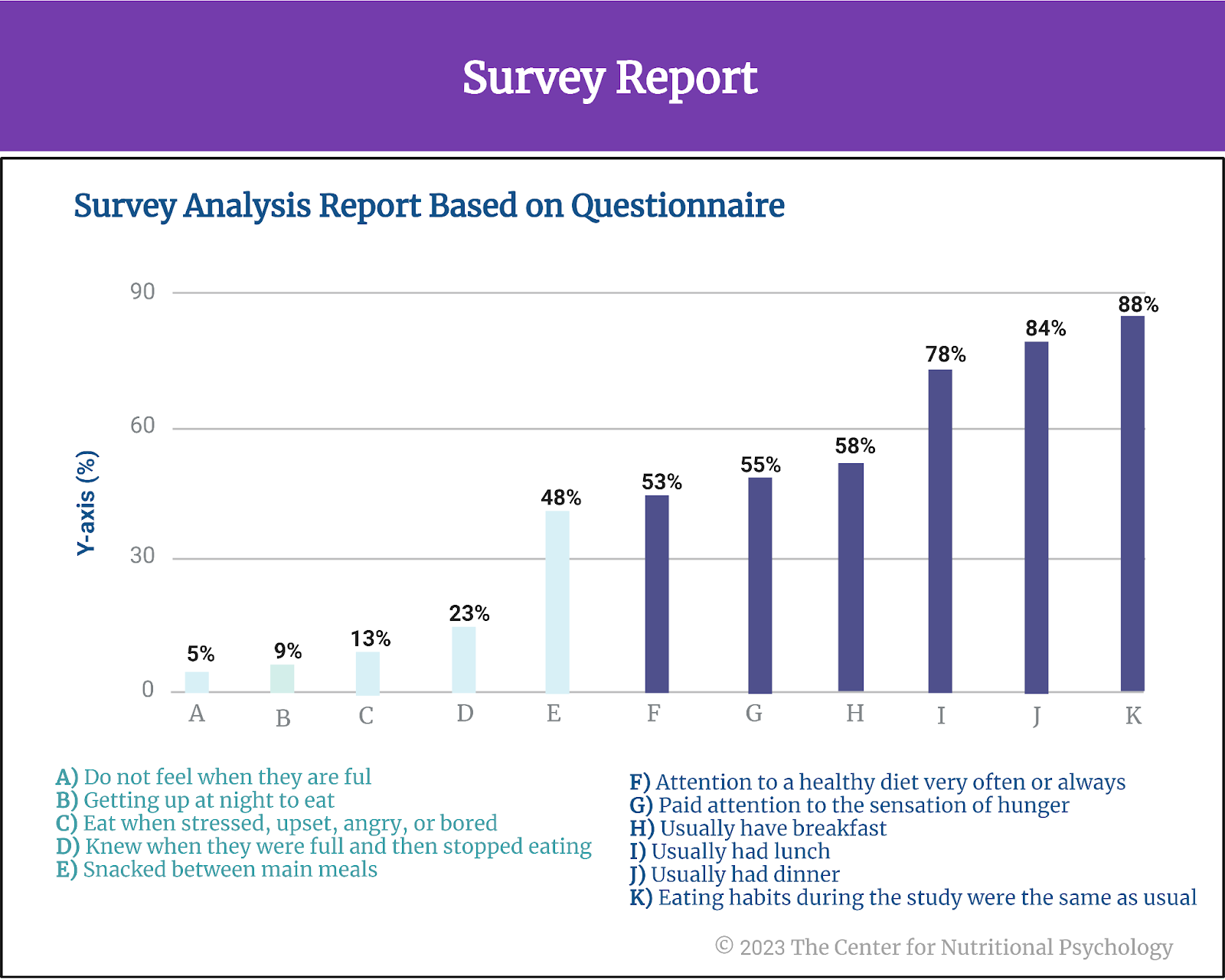

Participants rarely skipped dinner

Analysis of the responses to the final questionnaire (see Figure 5) showed that some participants often skipped meals, but not all equally. 58% reported that they usually have breakfast, 78% usually had lunch, and 84% usually had dinner. 48% snacked between main meals. 9% reported getting up at night to eat. 88% declared that their eating habits during the study were the same as usual.

53% of the participants paid close attention to maintaining a healthy diet, either very often or always, and 55% paid attention to the sensation of hunger. The main motivation for eating was hunger and because participants liked the meal. 23% of participants stated they knew when they were full and then stopped eating. 63% reported that from time to time, they would continue to eat even though they were aware that they were full. 13% said they eat when stressed, upset, angry, or bored. Less than 5% reported that they do not feel when they are full and that they orient themselves based on the size of the meal.

Figure 5. Survey Report

When hungry, participants were more often angry, irritable and felt less pleasure

The results demonstrated a strong association between hunger and heightened feelings of anger, irritability, and reduced pleasure. Surprisingly, researchers also observed that participants with higher levels of dispositional anger tended to report higher levels of hunger.

Dispositional anger is a general tendency of an individual to experience anger more frequently and intensely across various situations. In contrast, the feeling of anger refers to a temporary and transient experience of anger.

The link of hunger with irritability, anger, and lower feeling of pleasure persisted even after participants’ sex, age, body mass index, dietary behavior, and dispositional anger were considered (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Hunger and emotions

Contrary to the study authors’ expectations, hunger was not associated with arousal.

Conclusion

Overall, the study suggests that the experience of being hangry is real. When study participants were hungry, they also tended to experience greater anger, irritability, and less pleasure. This happened in their natural environments while they were living their lives as usual, not in an artificial laboratory environment. It was also not a one-time occurrence – the findings resulted from 105 surveys taken five times daily across three weeks.

These results have important implications for understanding everyday experiences of emotions. They also help practitioners to effectively prevent interpersonal conflicts while ensuring productive behaviors and good relationships. Although the design of this study does not allow for cause-and-effect conclusions to be made, i.e., to conclude that hunger causes anger or vice versa, simply designing school or work schedules to ensure no one goes hungry could help prevent numerous interpersonal problems. Allocating sufficient time and opportunities to eat and reduce prolonged periods of hunger is an important tool for improving everyone’s well-being.

On an individual level, labeling one’s affective state as being “hangry” could allow individuals to make sense of that experience. This is very important as, unlike some other negative states, hunger can be easily resolved by simply eating something.

The paper “Hangry in the field: An experience sampling study on the impact of hunger on anger, irritability, and affect” was authored by Viren Swami, Samantha Hochstoeger, Erik Kargl, and Stefan Stieger.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252

Isherwood, C. M., van der Veen, D. R., Hassanin, H., Skene, D. J., & Johnston, J. D. (2023). Human glucose rhythms and subjective hunger anticipate meal timing. Current Biology, 33(7), 1321-1326.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.005

Lazarus, R. S., Yousem, H., & Arenberg, D. (1953). Hunger and Perception. Journal of Personality, 21(3), 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-6494.1953.TB01774.X

Levine, A. S., & Morley, J. E. (1981). Stress-induced eating in rats. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 241(1), R72–R76.

McKiernan, F., Houchins, J. A., & Mattes, R. D. (2008). Relationships between human thirst, hunger, drinking, and feeding. Physiology & Behavior, 94(5), 700. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2008.04.007

Swami, V., Hochstöger, S., Kargl, E., & Stieger, S. (2022). Hangry in the field: An experience sampling study on the impact of hunger on anger, irritability, and affect. PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0269629. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0269629

The Center for Nutritional Psychology. (2023). What is Nutritional Psychology? https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/what-is-nutritional-psychology/

Leave a comment