Binge Drinking in Adolescents Linked to Changed Composition of Bacteria in the Gut

If we drink multiple alcoholic beverages at once, this will lead to intoxication. But when we sober up, are the alcoholic effects gone or are there changes to our body that linger? A new study by Carbia and colleagues done at the University College Cork in Ireland aimed to identify changes in our body that can be used to detect binge drinking, even before this drinking habit leads to alcohol use disorder. These researchers studied potential links between binge drinking, changes to the gut microbiome, social cognition, and impulsivity. The second goal of the study was to identify the changes in our body that happen when we experience alcohol cravings by examining the associations of the microbiome composition and craving for alcohol.

This study was published in eBioMedicine and explores whether changes in the gut microbiome are associated with cravings for alcohol, and whether alterations in the composition of the gut microbiome due to binge drinking have detrimental effects on cognitive functioning, particularly in relation to social and emotional processing.

Let’s begin by learning more about binge drinking.

What is binge drinking?

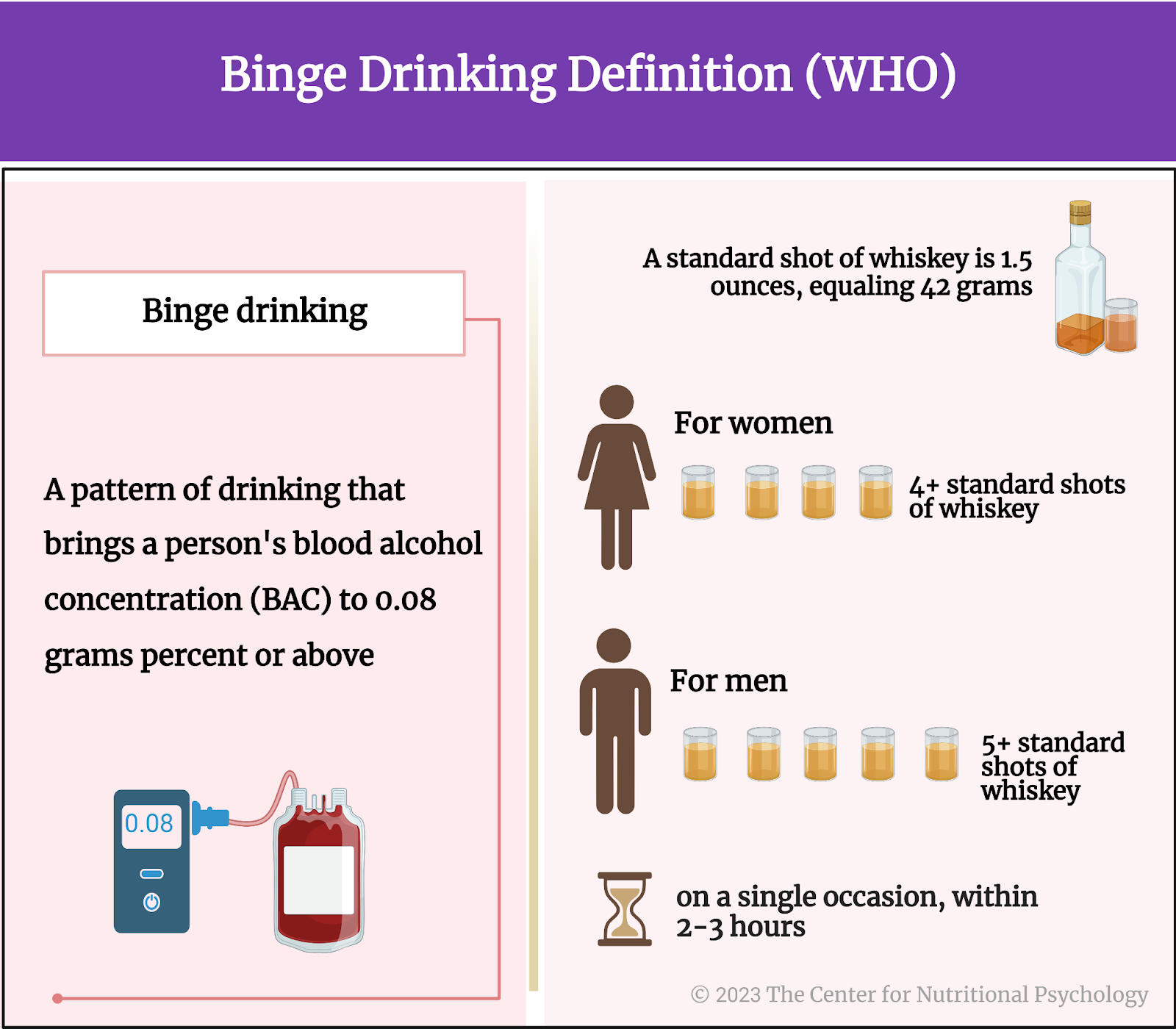

Binge drinking is defined as the consumption of excessive amounts of alcoholic beverages in a short period of time. It is the most frequent type of alcohol misuse during adolescence in Western countries (Carbia et al., 2023), and is most frequent in late adolescence, up to around 24 years of age (Sawyer et al., 2018). Binge drinking is associated with an increased risk of developing alcohol use disorder, but also other types of psychiatric disorders later in life.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a binge drinking episode as consuming at least 60 grams of pure alcohol on a single occasion, which leads to a blood alcohol concentration of 0.8 grams/liter or higher (Rolland et al., 2017). A standard shot of whiskey is 1.5 ounces, equaling 42 grams. Given 40% alcohol content, a standard shot of whiskey contains .6 oz or a bit less than 17 grams of alcohol. A binge drinking episode would thus be any single occasion on which a person consumes 4 or more standard shots of whiskey (or of a similar alcoholic beverage) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Binge drinking episode per WHO

The microbiome-gut-brain axis

The human gut microbiome consists of a plethora of microorganisms (predominantly bacteria, but also archaea, viruses, and fungi) that inhabit the human gastrointestinal tract, primarily the colon or large intestine. These microorganisms have co-evolved with the human host over millions of years, forming a complex ecosystem that plays a critical role in human health and disease (Cryan et al., 2019).

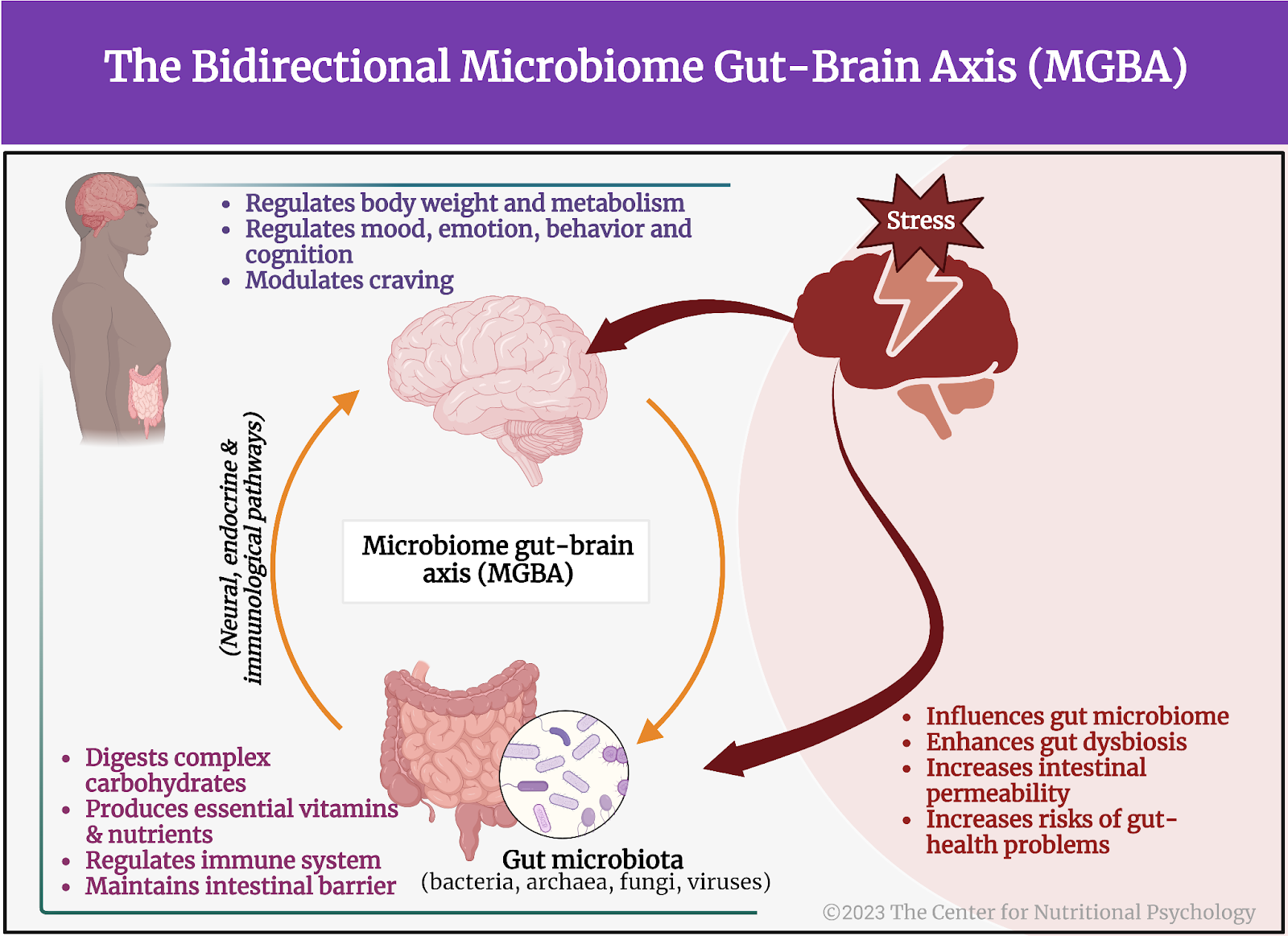

The MGBA is a bi-directional communication system existing between our gut, its microbiome, and our brain. This communication system is facilitated by various signaling pathways and molecules which together perform a wide range of functions essential for human health — including digesting complex carbohydrates, producing essential vitamins and nutrients, regulating the immune system, and maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier (which serves as a physical and biochemical barrier between the gut and the rest of the body’s organs).

The microbiome gut-brain axis regulates processes beyond the gut, including metabolism, body weight, and brain functions involving mood, emotion, craving, behavior, and cognition. And because this communication system is bidirectional, just as the gut microbiome can influence mood and stress states, mood and stress states can, in turn, influence the gut microbiome — leading to gut dysbiosis, intestinal permeability, and other gut-related health problems (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Microbiome gut-brain axis and stress

The gut microbiome in individuals suffering from binge drinking and alcohol use disorder

Several studies have explored the link between altered gut microbiome in the development of alcohol use disorder and binge drinking in young people (Rodríguez-González et al., 2021; Gorky & Schwaber, 2016).

In the scope of alcohol use disorder treatment, for example, studies demonstrate that patients who abruptly cease drinking alcohol show increased gut permeability and changes in the composition of their gut microbiome. They also show higher levels of cytokines and cortisol (Adams et al., 2020). The increased levels of cytokines and cortisol in patients’ circulation are associated with the severity of their alcohol use disorder, and the intensity of their craving for alcohol.

Since binge drinking can negatively impact the microbiome-gut-brain axis and contribute to the development of alcohol-related health problems, targeting the gut microbiome holds promise as a potential method for reducing alcohol-related harm in this population.

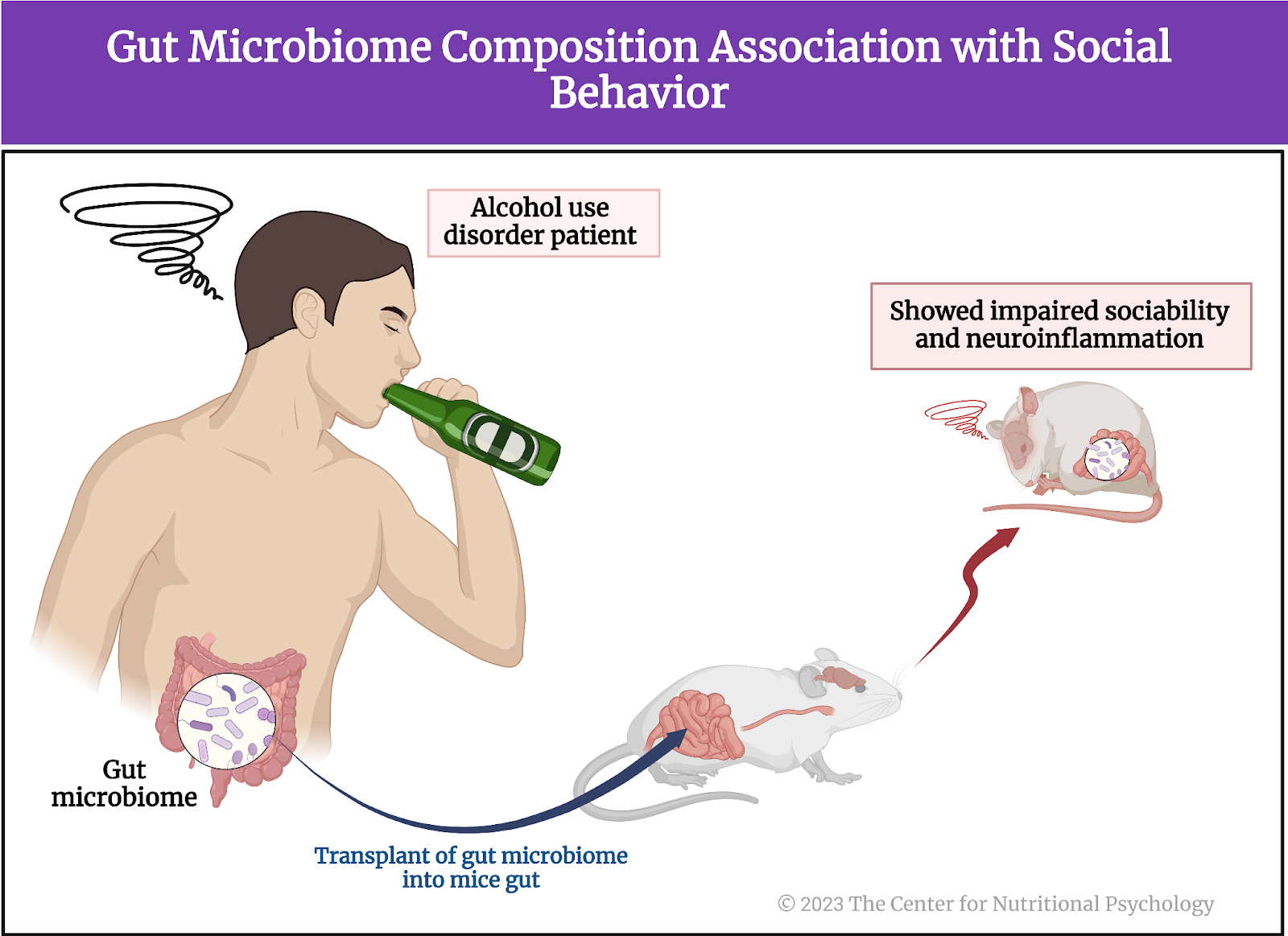

The gut microbiome composition might be associated with social behavior

Numerous studies demonstrate that gut microbiota composition appears to be connected to social behavior (Johnson, et. al, 2022; Sylvia, et al., 2018). An experiment where the gut microbiome from patients suffering from alcohol use disorder was transplanted into the guts of mice, showed that this action impaired the sociability of the mice and also lead to certain disturbances in their brain function (Leclercq et al., 2020) such as neuroinflammation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gut microbiome composition association with social behavior

This and other findings have led researchers to postulate that the gut microbiome might play a role in the development of alcohol use disorder, and also in other psychiatric disorders characterized by problems in social cognition and functioning.

The gut microbiome might play a role in the development of alcohol use disorder.

The study of young Irish binge drinkers

A 2023 study by Carbia and colleagues aimed to identify early biomarkers of alcohol misuse by exploring the gut microbiome and neurocognitive correlates in young binge drinkers who do not have an alcohol use disorder (Carbia et al., 2023).

They reasoned that because of the intense development occurring during adolescence, people have increased vulnerability to developing alcohol use disorder (and other psychiatric disorders) during this stage of life. They purport that it is possible that factors creating this vulnerability go beyond the developing brain of a young person and extend to specificities of the gut microorganism composition.

As previously mentioned, these authors wanted to study potential links between binge drinking, changes to the gut microbiome, social cognition, and impulsivity. Social cognition and impulsivity are two cognitive domains most often linked to increase in alcohol drinking. The second goal of the study was to identify the biomarkers of alcohol craving by examining the associations between changes to the microbiome composition and craving for alcohol.

Because of the intense development during adolescence, people have increased vulnerability to developing alcohol use disorder (and other psychiatric disorders) during this stage of life.

Study participants and procedure

Study participants were 71 healthy persons, between 18 and 25 years of age, living in Cork, Ireland. Those excluded from the study were prospective participants who never drank alcohol, whose scores on an alcohol use assessment test indicated alcohol use disorder and those who had a family history of alcoholism. Participants were also excluded if they had any other mental disorder, or were using drugs or any medications.

After recruitment, participants underwent a clinical interview in which researchers collected their demographic information, made clinical assessments, and collected a range of other data, such as information about their diets. During their second visit, participants underwent neuropsychological evaluation and researchers collected their biological samples (saliva, hair, blood, stool). Three months later, participants reported their alcohol use and craving. Participants were paid up to 50 EUR for their participation in the study.

It is possible that factors creating vulnerability in young people for alcohol disorders go beyond the developing brain and extend to specificities of the gut microorganism composition.

Measures and assessments

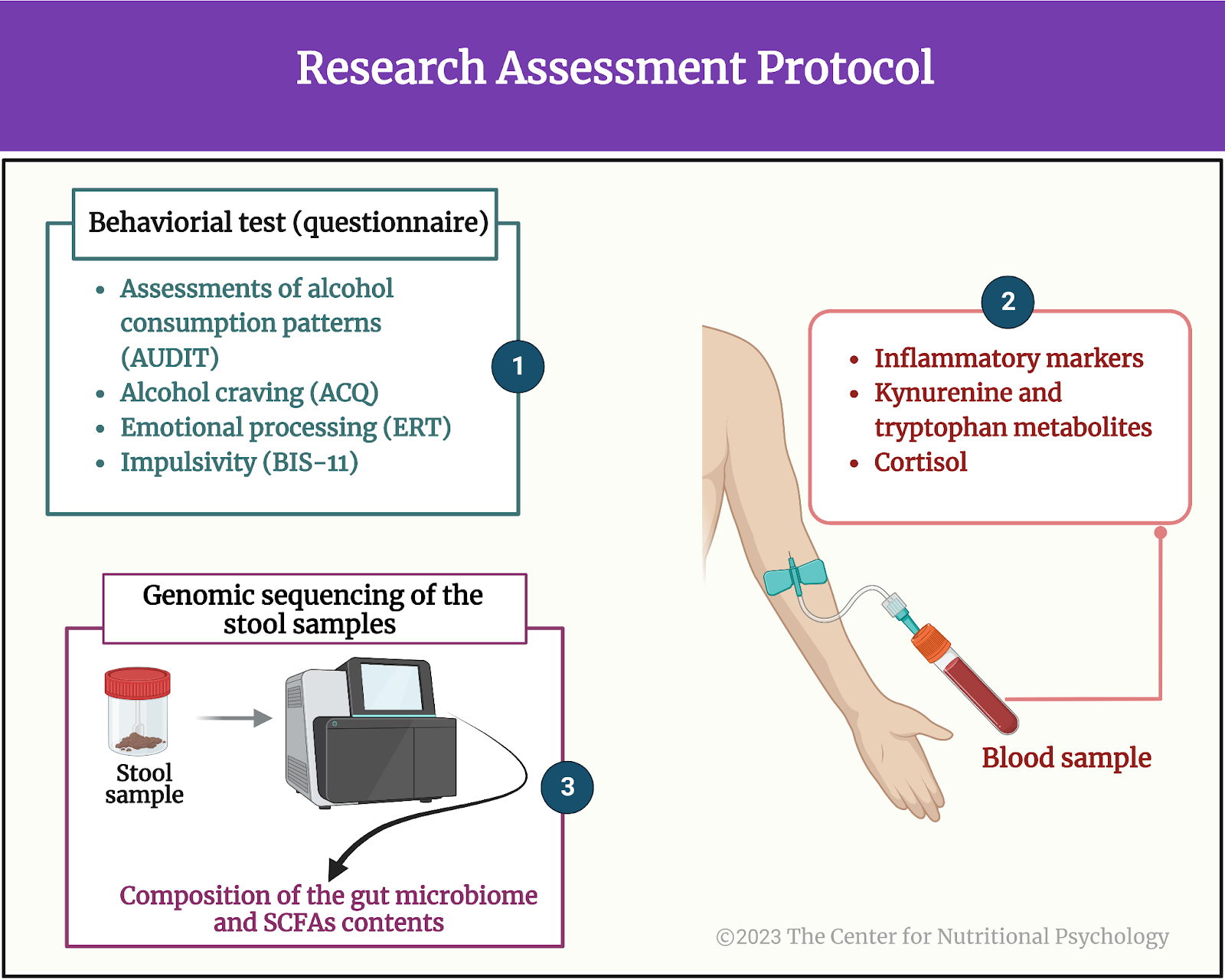

In the scope of the study, participants completed assessments of alcohol consumption patterns (the AUDIT questionnaire and the Alcohol Timeline Follow-Back, TFLB), alcohol craving (the Alcohol Craving Questionnaire – Short Form, ACQ), emotional processing (the Emotion Recognition Task, ERT and the Affective Go/No-Go task from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery, CANTAB), and impulsivity (The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, BIS-11).

Researchers also made assessments of participants’ inflammatory markers from blood samples of kynurenine and tryptophan (metabolites suspected to be a part of the microbiome-gut-brain axis communication pathway) and cortisol. Genomic sequencing of the stool samples was conducted for the purposes of identifying composition of the gut microbiome and short-chain fatty acid contents — another suspected component of the microbiome-gut-brain communication axis (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Research assessment protocol

Binge drinkers have higher alcohol cravings and are worse at recognizing emotions.

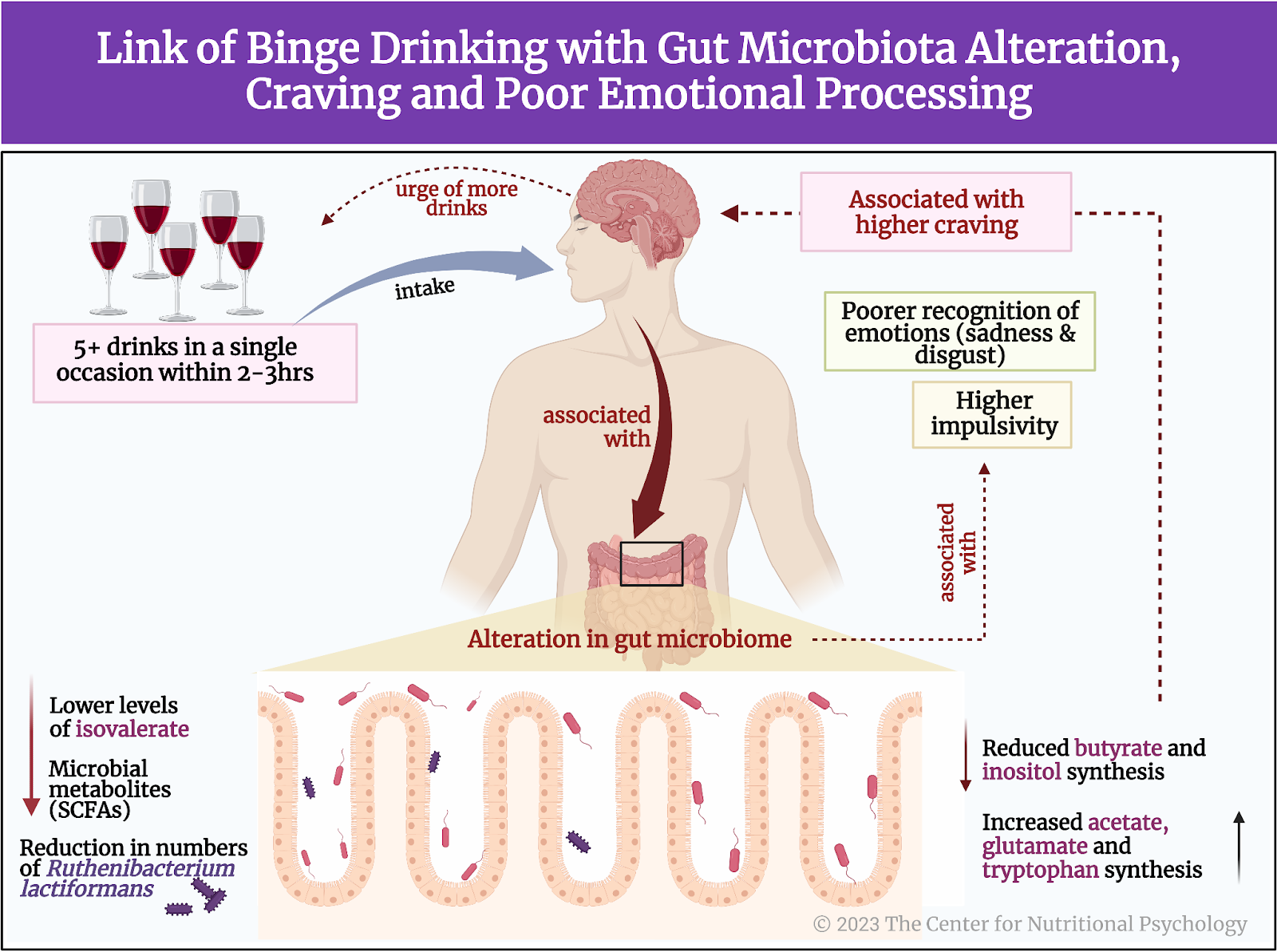

Results showed that participants who had more binge drinking episodes had higher cravings for alcohol. Participants who had a higher number of drinks within a drinking episode were also less able to recognize sadness and disgust. People who drank more were slower to respond when they gave correct answers to these tests. They also scored higher on impulsivity.

Binge drinking and the gut microbiome

Recent binge drinking episodes were associated with higher microbiome alterations, including changes to how widespread multiple species of bacteria were (referred to as microbial diversity). Higher numbers of drinks per binge drinking session were associated with lower levels of isovalerate, one type of branched-chain saturated fatty acid, thought to be involved in how the gut microbiome interacts with body processes outside the gut. Greater craving for alcohol was found to be associated with reductions in numbers of the gut bacteria Ruthenibacterium lactiformans. It was also associated with changes in levels of a number of compounds thought to be involved in the microbiome-gut-brain axis as well as those involved in the gut-metabolic interactions. Notably, reduced butyrate and inositol synthesis and increased acetate, glutamate, and tryptophan synthesis were associated with higher cravings.

Let’s see this visually in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Link of binge drinking with gut microbiota alteration, craving, and poor emotional processing

Conclusion

This study showed that binge drinking, the most common pattern of alcohol misuse in adolescence, is linked with changes to the gut microbiome and specific cognitive impairments. The study also revealed that changes in the gut microbiome are linked with increased cravings for alcoholic beverages. This was shown to happen in participants without alcohol addiction (i.e., before the alcohol use disorder has developed). These findings open the possibility to develop methods for predicting alcohol drinking habits and possibly alcohol-related social functioning impairments by analyzing gut microbiota composition from stool samples. They could also lead to novel dietary or pre/probiotic interventions directed at improving early alcohol-related alterations in the gut microbiota of young drinkers.

More about the gut microbiome and its connection to psychological, cognitive, behavioral and psychosocial functioning and mental health can be found in NP 120 (scheduled to be published in May 2023). NP 120 is part of the Introductory Certificate in Nutritional Psychology through the Center for Nutritional Psychology.

The paper “The Microbiome-Gut-Brain axis regulates social cognition & craving in young binge drinkers” was authored by Carina Carbia, Thomaz F. S. Bastiaanssen, Luigi Francesco Iannone, Rubén García-Cabrerizo, Serena Boscaini, Kirsten Berding, Conall R. Strain, Gerard Clarke, Catherine Stanton, Timothy G. Dinan, and John F. Cryan.

References

Adams, C., Conigrave, J. H., Lewohl, J., Haber, P., & Morley, K. C. (2020). Alcohol use disorder and circulating cytokines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 89, 501-512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.08.002

Carbia, C., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Iannone, F., García-cabrerizo, R., Boscaini, S., Berding, K., Strain, C. R., Clarke, G., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2023). The Microbiome-Gut-Brain axis regulates social cognition & craving in young binge drinkers. EBioMedicine, In press), 104442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104442

Gorky, J., & Schwaber, J. (2016). The role of the gut–brain axis in alcohol use disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 65, 234-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.06.013

Johnson, K. V., Watson, K. K., Dunbar, R. I. M., & Burnet, P. W. J. (2022). Sociability in a non-captive macaque population is associated with beneficial gut bacteria. Frontiers in microbiology, 13, 1032495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1032495

Leclercq, S., Le Roy, T., Furgiuele, S., Coste, V., Bindels, L. B., Leyrolle, Q., Neyrinck, A. M., Quoilin, C., Amadieu, C., Petit, G., Dricot, L., Tagliatti, V., Cani, P. D., Verbeke, K., Colet, J. M., Stärkel, P., de Timary, P., & Delzenne, N. M. (2020). Gut Microbiota-Induced Changes in β-Hydroxybutyrate Metabolism Are Linked to Altered Sociability and Depression in Alcohol Use Disorder. Cell Reports, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CELREP.2020.108238

Rodríguez-González, A., Vitali, F., Moya, M., De Filippo, C., Passani, M. B., & Orio, L. (2021). Effects of Alcohol Binge Drinking and Oleoylethanolamide Pretreatment in the Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.731910

Rolland, B., Chazeron, I. de, Carpentier, F., Moustafa, F., Viallon, A., Jacob, X., Lesage, P., Ragonnet, D., Genty, A., Geneste, J., Poulet, E., Dematteis, M., Llorca, P. M., Naassila, M., & Brousse, G. (2017). Comparison between the WHO and NIAAA criteria for binge drinking on drinking features and alcohol-related aftermaths: Results from a cross-sectional study among eight emergency wards in France. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 175, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2017.01.034

Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

Sylvia, K. E., & Demas, G. E. (2018). A gut feeling: Microbiome-brain-immune interactions modulate social and affective behaviors. Hormones and behavior, 99, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.02.001

Leave a comment