- A systematic review published in Nutrition Reviews found that adherence to a Mediterranean diet could be a protective factor for mental health in children

- The review included 13 studies, 2 of which were randomized controlled trials, and seven were found to be of high quality

- Analyzed studies included 3058 children between 8 and 16 years of age

“You are what you eat,” the old saying goes. It means one must eat good food to stay healthy and fit. This link between eating well and staying healthy is obvious – our body needs specific nutrients to function. If we do not obtain them through food, serious health consequences will follow.

Diet and health

Science has known for centuries that a lack of specific nutrients can lead to serious health conditions. Nutrient deficiency diseases such as anemia (caused by a lack of iron, leading to fatigue, weakness, and pale skin), scurvy (caused by a deficiency of vitamin C, leading to bleeding gums, joint pain, and anemia), pellagra (caused by a deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3), leading to dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia) or hypothyroidism (caused by a deficiency of iodine, leading to fatigue, weight gain, and depression) have been described and well understood for over 100 years.

However, studies in the past several decades revealed much more nuanced links between diet and health. Unlike nutrient deficiency diseases, these new studies link adverse health outcomes to more complex dietary patterns (i.e., patterns involving different foods containing many different nutrients and micronutrients in specific ratios or entire food consumption patterns referred to as diets).

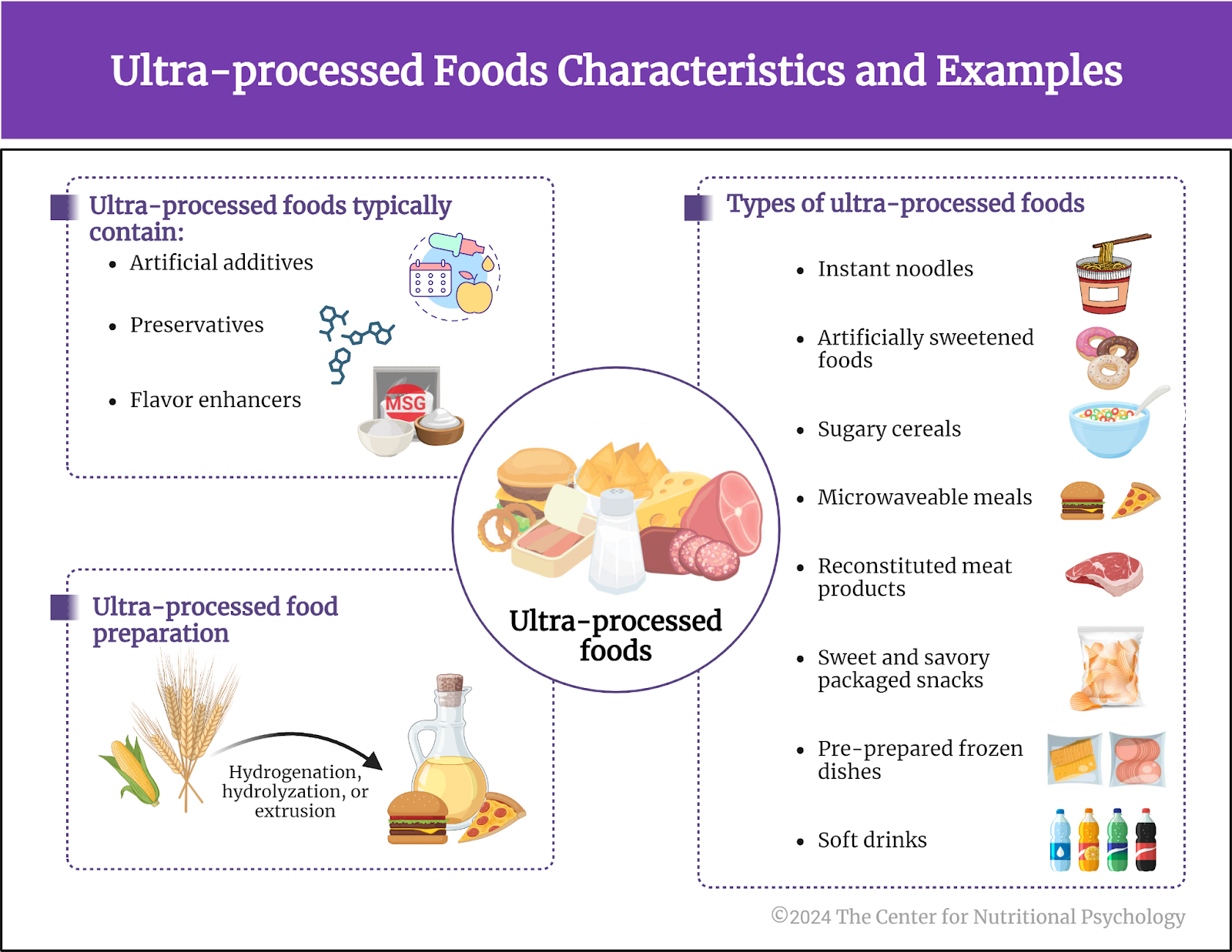

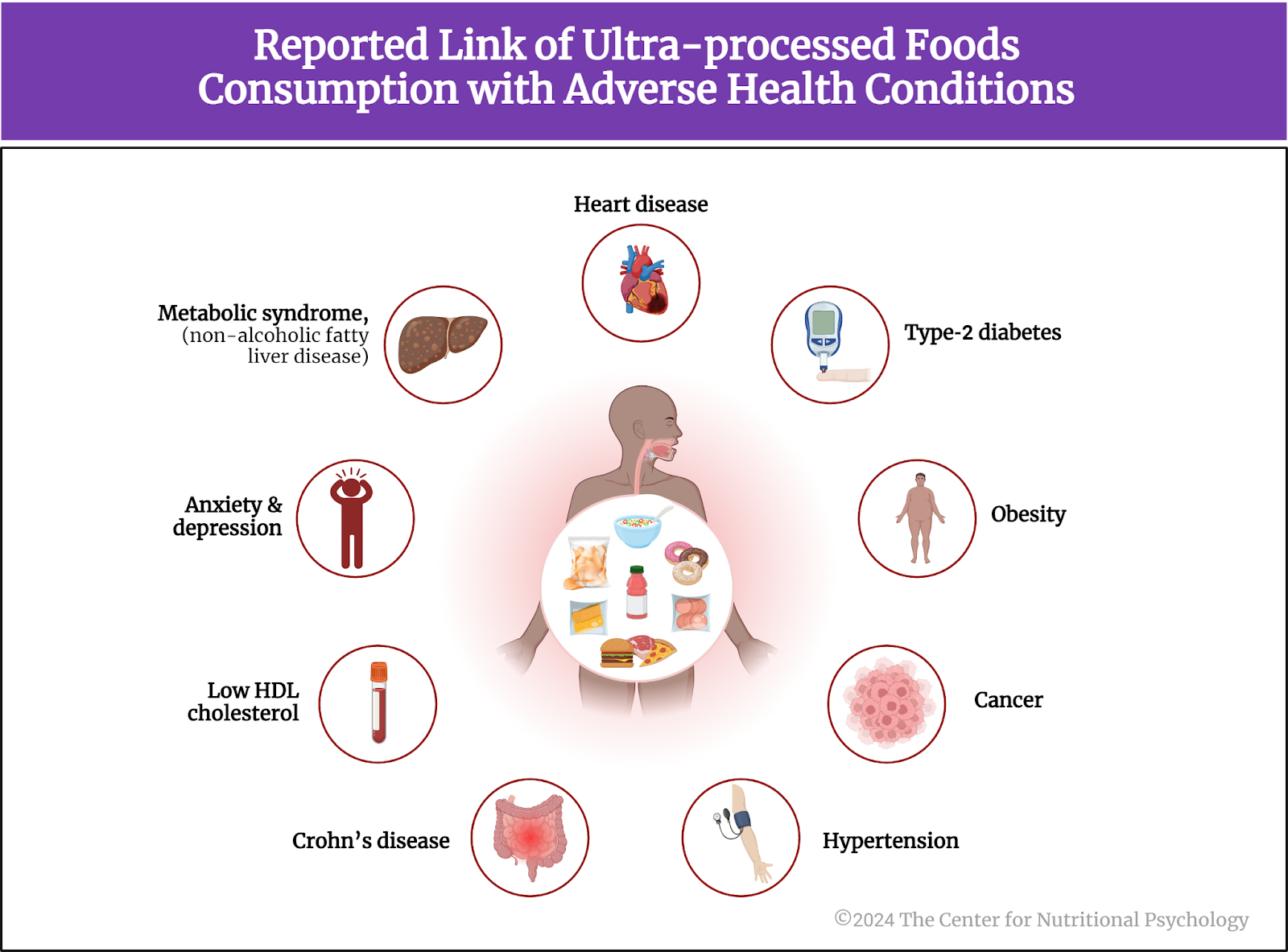

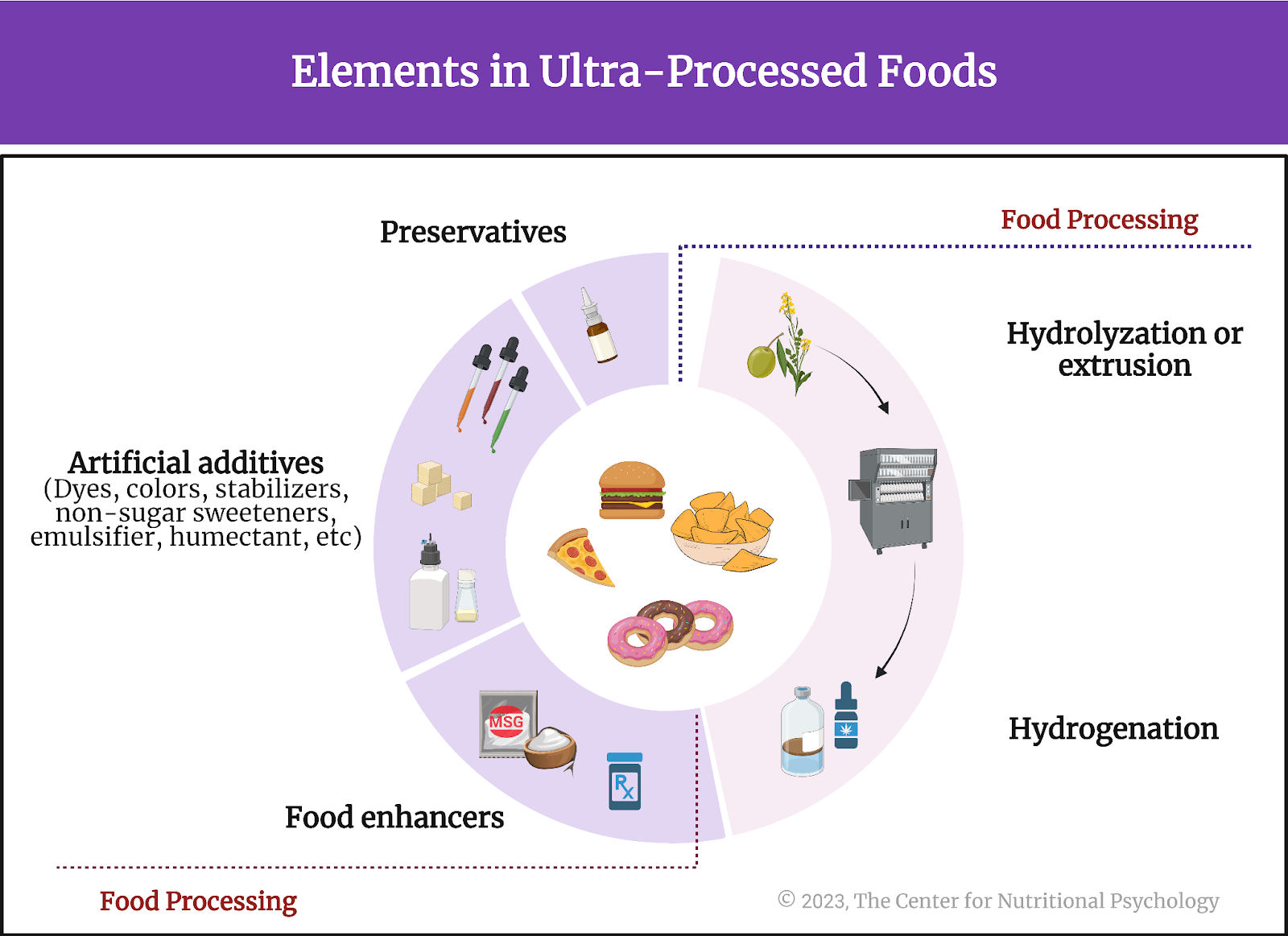

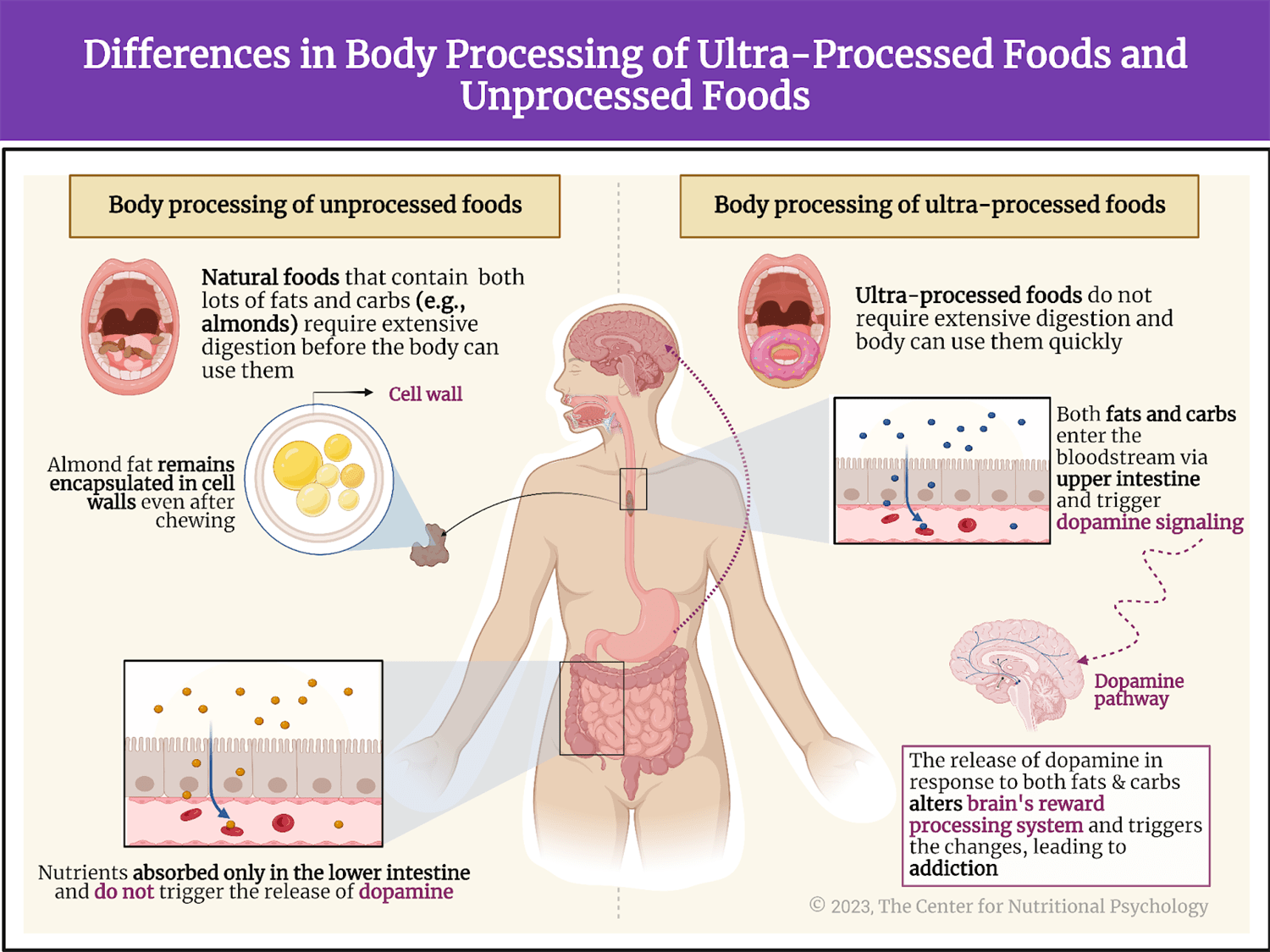

For example, studies report that excessive intake of refined sugars is associated with increased risks of cardiovascular diseases, depression, type 2 diabetes, and even cancer (Hedrih, 2023; Huang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024). Consumption of ultra-processed foods, i.e., food items created through extensive industrial processing, has also been linked to a wide range of adverse health outcomes ranging from cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases, depression, and anxiety to cancer (Lane et al., 2024) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Link of ultra-processed food to disease

These studies effectively tell us which foods or dietary patterns to avoid. But all living organisms need to eat if they want to live. So, are there dietary patterns that may protect our health? One such pattern might be the Mediterranean diet.

The Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet is a pattern inspired by the traditional eating habits of people in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. It emphasizes the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil, with a moderate intake of fish and poultry and limited consumption of red meat and sweets. This diet also includes moderate wine consumption, usually with meals.

Studies have shown that this diet is associated with numerous health benefits, including reduced risks of heart disease and diabetes (Salas-Salvadó et al., 2018; The InterAct Consortium, 2011). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is even associated with a slightly lower risk of several types of cancer and a lower overall risk of dying from cancer (Schwingshackl & Hoffmann, 2016).

The current study

Study author Patricia Camprodon-Boadas and her colleagues wanted to investigate the association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and mental health outcomes in children and adolescents (Camprodon-Boadas et al., 2024).

These authors note that childhood and adolescence are critical periods in the development of mental illness. Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health issue among children, followed by behavior disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders. Girls generally tend to have higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders, while boys are more susceptible to behavior disorders. Drug use disorders are equally common among girls and boys (Camprodon-Boadas et al., 2024). But could this diet be a protective factor against these disorders?

Childhood and adolescence are critical periods in the development of mental illness

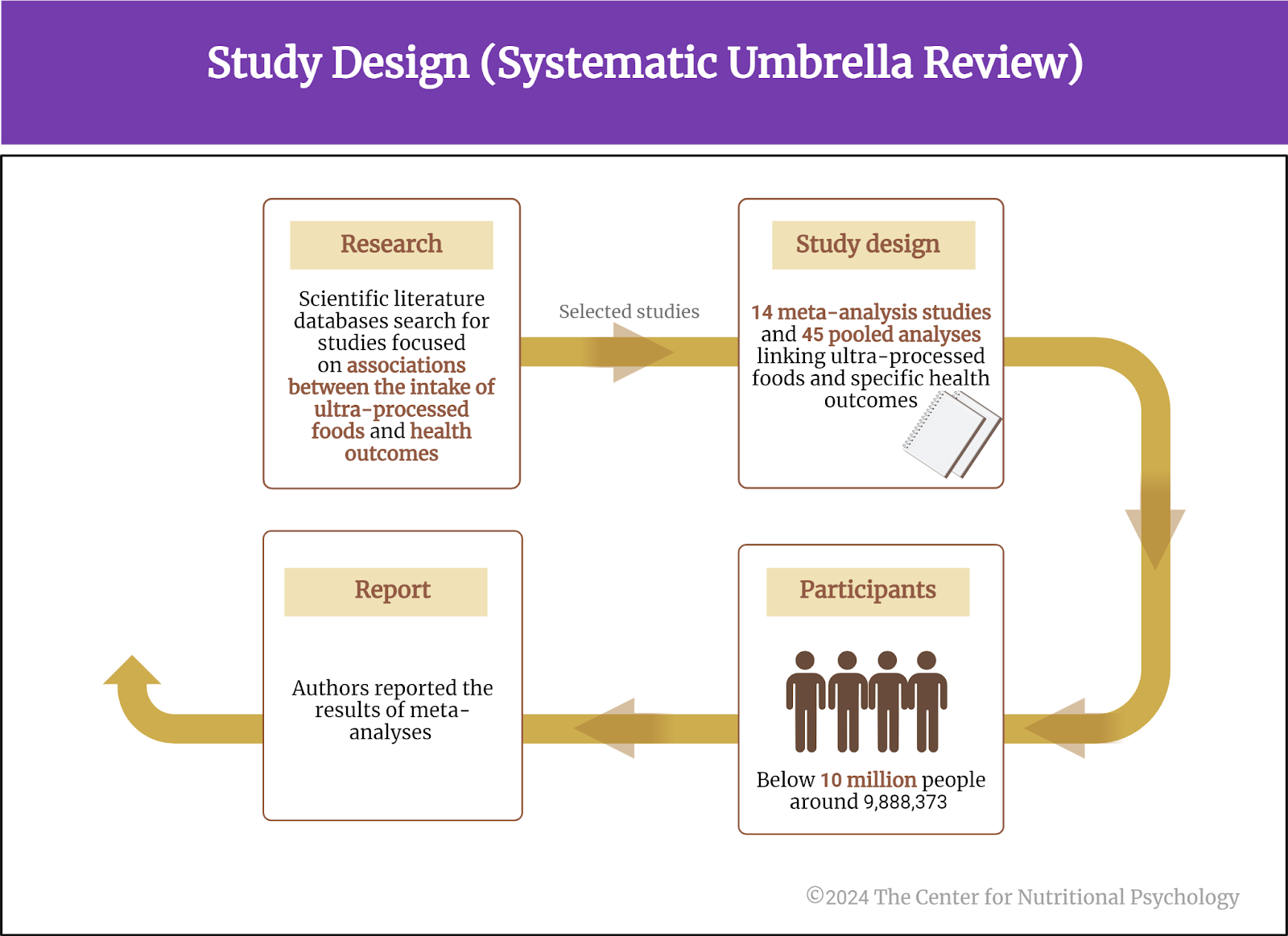

These authors conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of research articles in English and Spanish that investigated the links between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and mental health symptoms in children and adolescents.

Their search of several scientific article databases initially yielded 450 articles. However, after the authors removed duplicates and read these articles in detail to examine whether they contained the data they needed, the number of articles fell to 13.

Eight of the studies described in these articles were conducted in Spain, while the remaining five articles came from Iran, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. One study included participants from five different countries. Two of the studies were randomized controlled trials (researchers had participants eat different diets to test their effects), and one study was longitudinal.

The 13 studies included 3058 children between 8 and 16 years of age. The studies used different ways to assess adherence to the Mediterranean diet, but most of them used the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index, a 16-item questionnaire. Study authors found 7 of these studies to be of high quality (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study Procedure (Camprodon-Boadas et al., 2024)

High adherence to Mediterranean diet was linked to lower odds of ADHD

4 of the 13 studies examined the links between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Their results indicated that children and adolescents with high adherence to the Mediterranean diet had 30% lower odds of suffering from ADHD.

Two studies examined the links between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and impulsivity. 1 of them reported that participants with higher impulsivity tended to have low adherence to a Mediterranean diet, while the other did not find this link. 1 study found no relationship between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and attention capacity

Children and adolescents with high adherence to the Mediterranean diet were less likely to suffer from depression or anxiety

Five studies examined the links between the Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms. Of these, four found that participants with depressive symptoms showed much lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Conversely, participants with high adherence to the Mediterranean diet were less likely to suffer from depression and had fewer depressive symptoms.

Four studies examined the association between the Mediterranean diet and anxiety. 2 of these studies found participants highly adhering to the Mediterranean diet to have fewer anxiety symptoms. In contrast, the other 2 found no such association (see Figure X).

Figure 3. Findings (Camprodon-Boadas et al., 2024)

Conclusion

Overall, the results reported by examined studies were not uniform, but the majority found higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet associated with fewer mental health issues.

The majority found higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet associated with fewer mental health issues

At the moment, it remains insufficiently clear whether it is the Mediterranean diet that reduces the risks of developing mental health issues or the absence of mental health issues that leads to higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet. A possibility exists that adherence to the Mediterranean diet might indeed be a protective factor for the mental health of children and adolescents.

The paper “Mediterranean Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review” was authored by Patricia Camprodon-Boadas, Aitana Gil-Dominguez, Elena De la Serna, Gisela Sugranyes, Iolanda Lazaro, and Immaculada Baeza.

Camprodon-Boadas, P., Gil-Dominguez, A., De La Serna, E., Sugranyes, G., Lázaro, I., & Baeza, I. (2024). Mediterranean Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrition Reviews, nuae053. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuae053

Hedrih, V. (2023, June 6). Health Consequences of High Sugar Consumption. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/health-consequences-of-high-sugar-consumption/

Huang, Y., Chen, Z., Chen, B., Li, J., Yuan, X., Li, J., Wang, W., Dai, T., Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wang, P., Guo, J., Dong, Q., Liu, C., Wei, Q., Cao, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 381, e071609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071609

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., Ashtree, D. N., McGuinness, A. J., Gauci, S., Baker, P., Lawrence, M., Rebholz, C. M., Srour, B., Touvier, M., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Segasby, T., & Marx, W. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

Salas-Salvadó, J., Becerra-Tomás, N., García-Gavilán, J. F., Bulló, M., & Barrubés, L. (2018). Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: What Do We Know? Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 61(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2018.04.006

Schwingshackl, L., & Hoffmann, G. (2016). Does a Mediterranean-Type Diet Reduce Cancer Risk? Current Nutrition Reports, 5(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0141-7

The InterAct Consortium. (2011). Mediterranean Diet and Type 2 Diabetes Risk in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Study. Diabetes Care, 34(9), 1913–1918. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0891

Zhang, L., Sun, H., Liu, Z., Yang, J., & Liu, Y. (2024). Association between dietary sugar intake and depression in US adults: A cross-sectional study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2018. BMC Psychiatry, 24(110), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05531-7