Scientists Propose that Ultra-Processed Foods be Classified as Addictive Substances

- An analysis commissioned by the BMJ argues that ultra-processed foods may be addictive

- Behaviors around ultra-processed food may meet the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder

- Classifying ultra-processed foods as addictive might open novel approaches to treating food addiction and policies intended to combat it

- Ultra-processed food addiction is estimated to occur in 14% of adults and 12% of children (Gearhardt et al., 2023).

We are all familiar with the devastating consequences resulting from the prolonged use of illicit drugs on an individual. In the beginning, the drugs produce pleasurable feelings by activating the brain’s reward system, and novice drug users experience euphoria, relaxation, or reduced stress. This, in turn, trains their brain to associate drug use with pleasure, reinforcing the desire to use drugs again. However, over time the body develops tolerance for the drug, and the individual needs to increase consumption to achieve the same effect continually. Ultimately, this changes the brain’s chemistry, which then becomes highly fixated on drug-induced pleasures and, consequently, less responsive to natural rewards. The desire for the drug becomes uncontrollable, and if this need is not met with more of the drug, unpleasant and difficult withdrawal symptoms occur. To avoid these symptoms, the drug user prioritizes his/her life to be exclusively focused on cycles of drug intake. This is damaging to both psychological and physical health and, in extreme cases, can lead to death. This development is what is usually referred to as addiction.

What is addiction?

A common definition of addiction is any behavior in which an individual has impaired control with harmful consequences. Individuals who recognize that the behavior is harming them or those they care about but still find themselves unable to stop engaging in that harmful behavior are considered addicted. Because addiction, in a way, violates one’s freedom of choice, it can be considered a disorder of motivation (West, 2001).

In certain types of addiction, an individual may experience withdrawal symptoms when the substance or behavior is not accessible. Withdrawal symptoms can vary depending on the specific substance involved, but common symptoms include anxiety, depression, irritability, nausea, vomiting, sweating, muscle aches, and intense cravings. Addiction can devastate an individual’s health, relationships, and overall well-being, making it a significant public health concern.

Can we become addicted to ultra-processed foods?

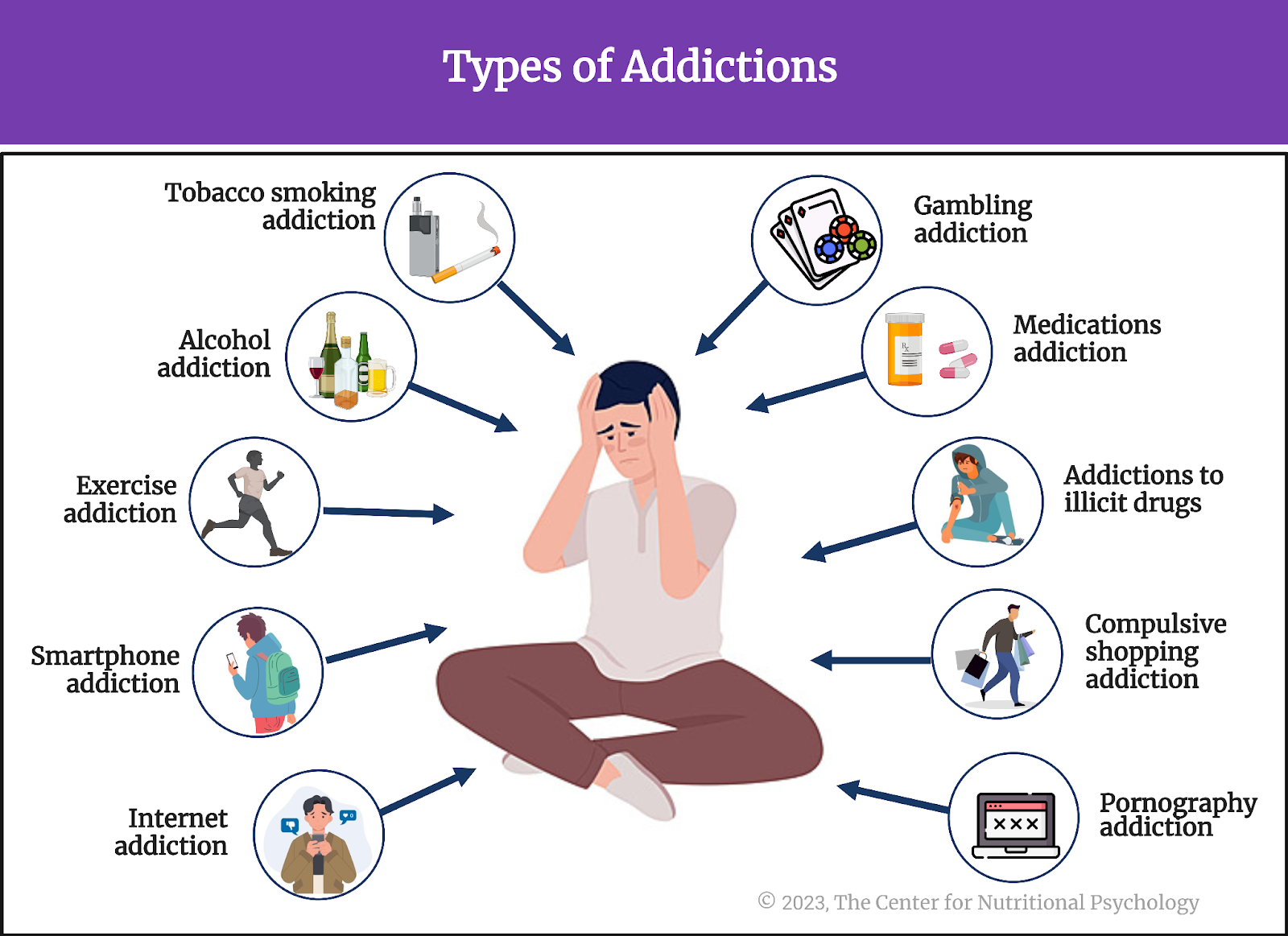

Although addictions to illicit drugs and alcohol get the most publicity, scientists have also recognized tobacco smoking addiction, gambling addiction, compulsive shopping addiction, smartphone addiction, internet addiction, exercise addiction, addiction to certain prescribed medications such as stimulants or benzodiazepines (medicines used to treat anxiety, sleep disorders, and seizures), pornography addiction, and many others (e.g., O’Brien, 2005; Rakić-Bajić & Hedrih, 2012; Ting & Chen, 2020) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of addictions

Many recent studies have supported the notion that individuals can display behaviors that meet the definition of addiction toward specific types of food. These behaviors include binge eating, or the inability to control food intake, strong cravings, and many other well-known characteristics of addictions (Gearhardt et al., 2011, 2023; Weingarten & Elston, 1990). Foods most often associated with food addictions are ultra-processed foods.

What are ultra-processed foods?

Almost all foods are processed to some extent. Humans process food to make it edible, preserve it, destroy harmful microorganisms, improve its taste, and for many other reasons. Some foods are not fit to eat without processing, and others would quickly spoil if left unprocessed. It is important to note that ultra-processed foods are not only processed, they have nutritionally lacking or unhealthy substances added.

Ultra-processed foods are formulations made mostly or entirely from derived substances and various additives with few intact unprocessed or minimally processed food components (Hedrih, 2023; Monteiro et al., 2019)

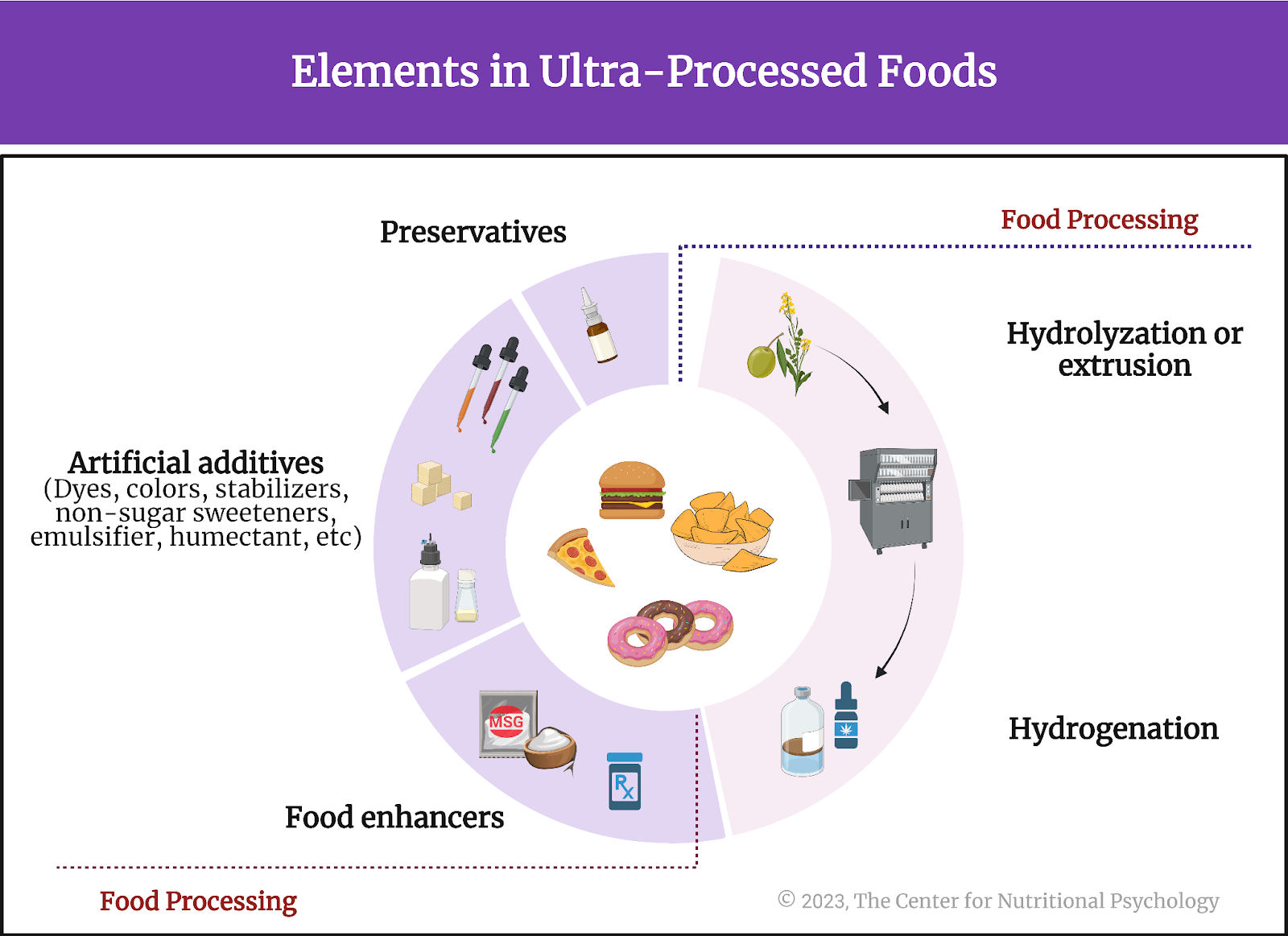

These foods typically contain artificial additives, preservatives, and flavor enhancers. Additives include dyes, color stabilizers, non-sugar sweeteners, de-foaming, anti-caking or glazing agents, emulsifiers, and humectants, among others. Some processes used in preparing ultra-processed foods, such as hydrogenation, hydrolyzation, or extrusion, are exclusively industrial processes that cannot be performed in a regular kitchen (see Figure 2). (Note: More about ultra-processed foods and their effects on the diet-mental health relationship can be found in NP 110: Introduction to Nutritional Psychology Methods through The Center for Nutritional Psychology).

Figure 2. Elements of ultra-processed foods

Examples of ultra-processed foods include instant noodles, artificial sweeteners, artificially sweetened beverages, sugary cereals, microwaveable meals, reconstituted meat products, sweet and savory packaged snacks, pre-prepared frozen dishes, and soft drinks (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Examples of ultra-processed foods

Ultra-processed foods are linked to various health problems

Ultra-processed foods are often low in nutritional value, high in calories, packed with various unhealthy ingredients, attractively packaged, and marketed intensely (see Figure 3). They are usually created with the intent of having a durable product that is highly palatable but also highly profitable due to the low cost of ingredients (Hedrih, 2023).

Studies have linked the consumption of ultra-processed foods with various health problems. Research indicates that individuals regularly consuming these foods have a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, certain types of cancer, and depression. (Monteiro et al., 2018; Samuthpongtorn et al., 2023). Despite this, the sales of these foods and their share in the dietary calorie intake are rising, both in high- and middle-income countries (Monteiro et al., 2019).

The analysis

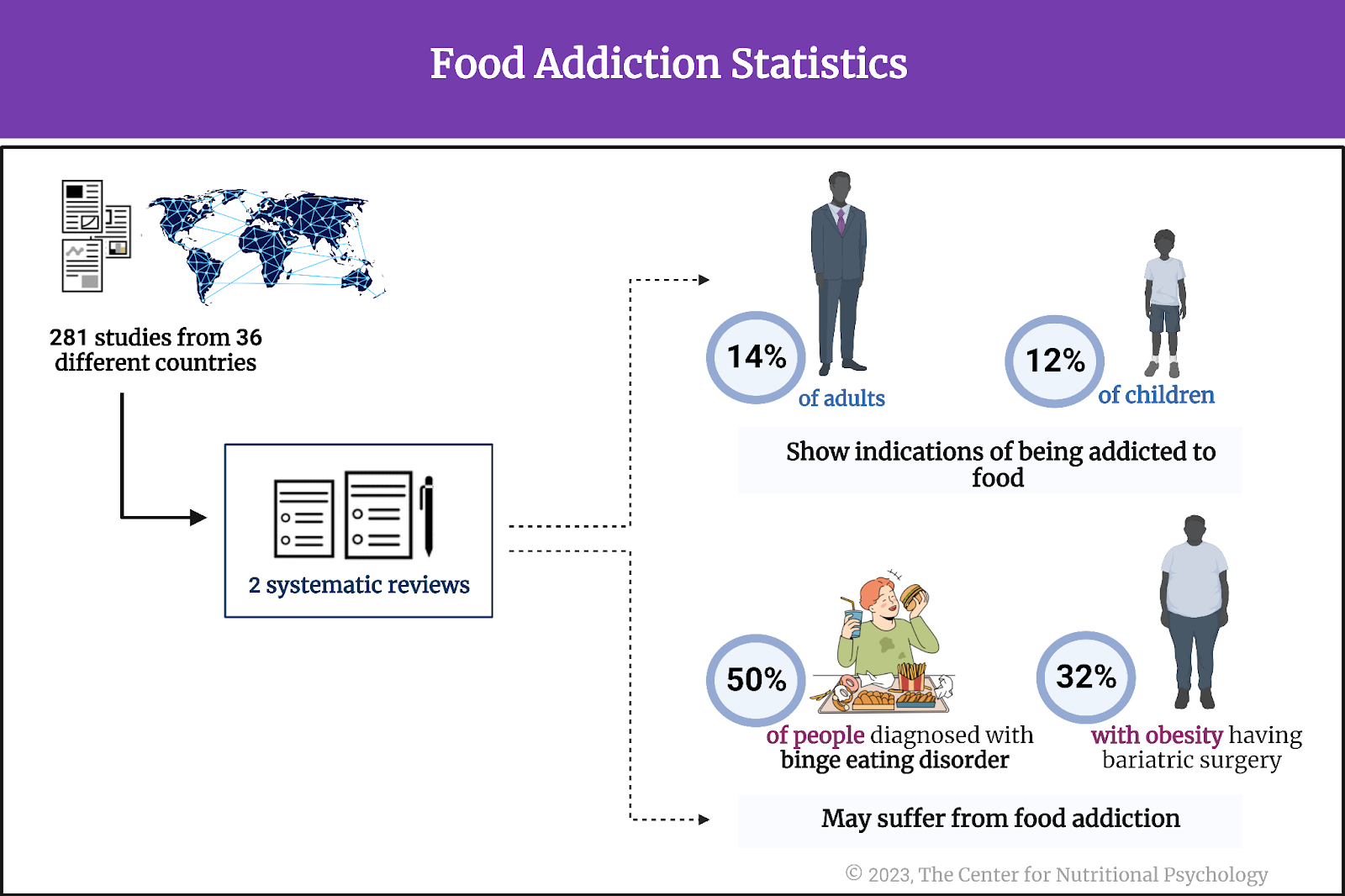

Professor Ashley Gaerhart and her colleagues start their analysis by noting that two reviews of 281 studies from 36 different countries found that 14% of adults and 12% of children show indications of being addicted to food. These levels are similar to shares of the population addicted to tobacco and alcohol. Studies also showed that 50% of people diagnosed with binge eating disorder and 32% of people struggling with obesity who are undergoing bariatric surgery may, indeed, suffer from food addiction (Figure X).

Figure 4. Food addiction statistics

These authors then analyze what might make a food addictive. According to them, not all foods have addictive potential. Research results indicate that foods with high levels of refined carbohydrates or added fats, such as sweets and salty snacks, are the most strongly implicated in addiction behaviors, such as losing control over consumption, excessive intake, and continued use despite negative consequences.

Foods with high levels of refined carbohydrates or added fats, such as sweets and salty snacks, are the most strongly implicated in addiction behaviors

What makes food addictive?

The foods described above are all ultra-processed. Unlike natural foods, they often contain high concentrations of both fats and carbohydrates. This is unlike natural or minimally processed foods with high carbohydrate content but little or no fat (e.g., apples) or high-fat content with little or no carbohydrates (e.g., certain types of fish or meat).

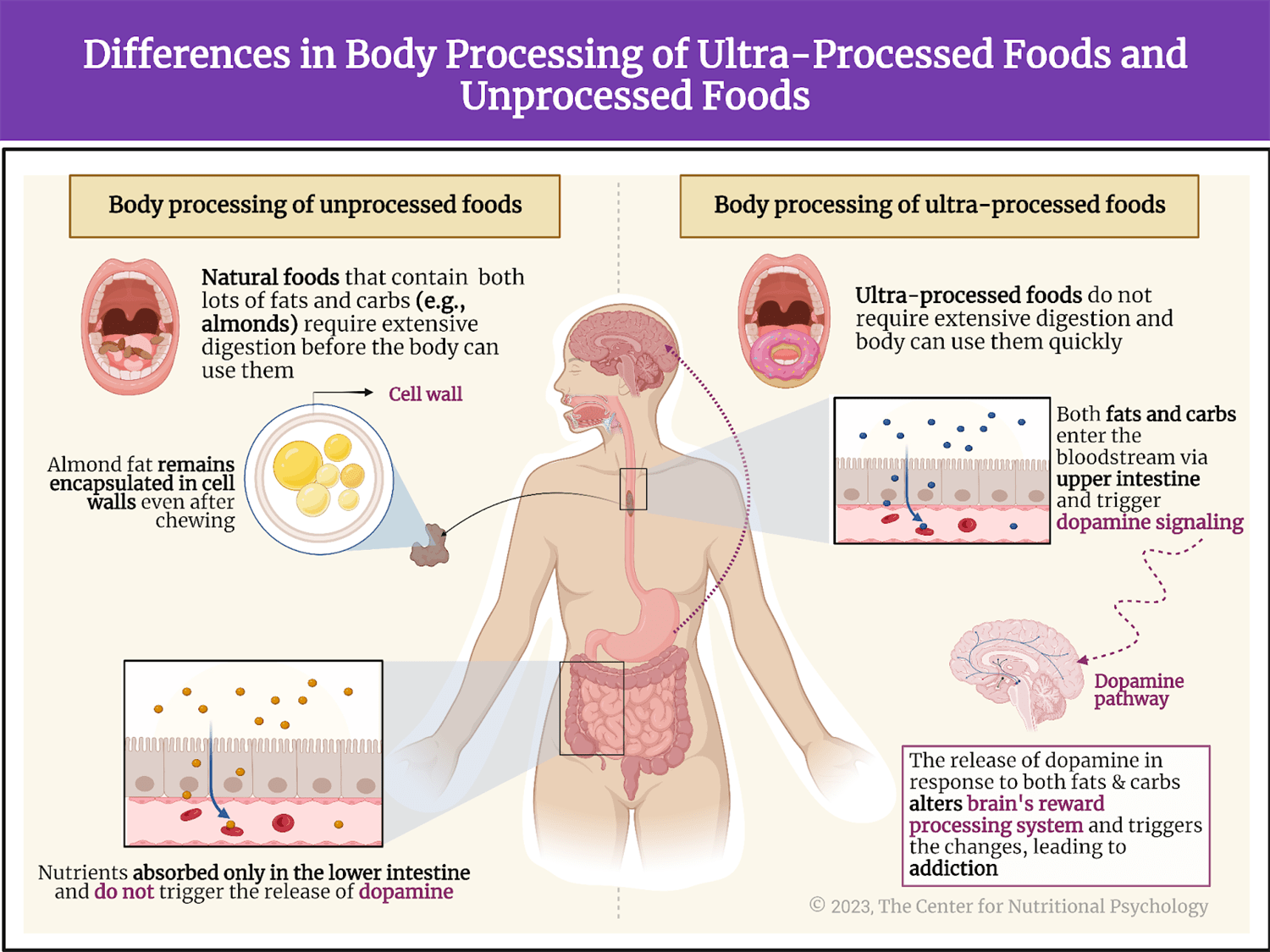

Even in rare cases when natural foods do contain large amounts of both fat and carbohydrates (e.g., almonds), they typically require extensive digestion before the body can use them. For example, almond fat remains encapsulated in cell walls even after chewing, which means it is unavailable to the body at the early stages of digestion. This is important because a natural and minimally processed food item, like almonds, takes a long time to break down, so nutrients will be absorbed only in the lower intestine and, therefore, do not trigger the release of dopamine (a neurotransmitter linked to feelings of reward and pleasure). Conversely, when an ultra-processed food undergoes digestion, it readily breaks down, and nutrients rapidly enter the bloodstream through the upper intestine, thereby triggering dopamine signaling, which ultimately induces feelings of pleasure.

Unlike natural foods, fats and carbohydrates in ultra-processed foods become swiftly available to the body during digestion which affects the pleasure response of the brain, contributing to the addictive nature of these foods. The reward of obtaining both of these micronutrients simultaneously is greater than the effect that either of them, individually, can have. This alters the brain’s reward processing system and triggers the changes, leading to addiction. Various additives found in ultra-processed foods that improve their taste and mouthfeel further strengthen these effects (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Differences in body processing of ultra-processed foods and unprocessed foods

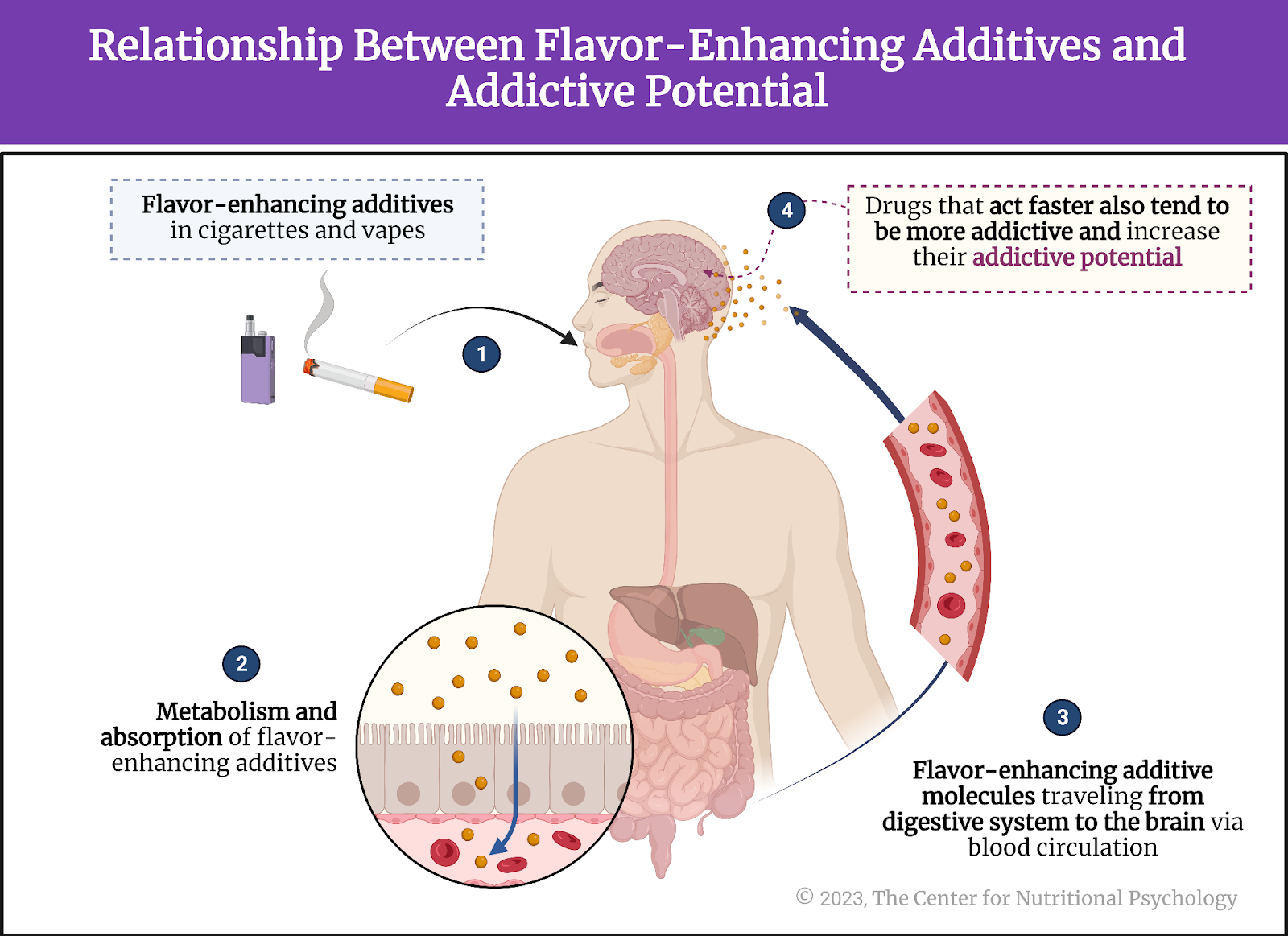

This mechanism is similar to the one determining the addictiveness of drugs. Drugs that act faster also tend to be more addictive. Studies indicate that flavor-enhancing additives in products, such as cigarettes, also increase their addictive potential (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Relationship between flavor-enhancing additives and addictive potential

But what do the critics say?

Not all scientists agree that food addiction is a real addiction. Unlike alcohol, tobacco, or cocaine, we need food to survive. Craving for food already has a name – hunger. Fats and carbohydrates are macronutrients that are needed to fuel the body in considerable amounts. Can an intense desire to consume substances needed for survival really be considered an addiction?

The authors of this analysis note that there is also the question of the addictive chemical. All other substances are addictions to a specific chemical, but such chemical has not been identified for foods. Substances such as alcohol, nicotine, or illicit drugs activate the brain’s reward system directly, but fat and carbohydrates do not do that.

However, these researchers argue that, although fat and carbohydrates do not activate the brain’s reward system directly, they can still activate it to a magnitude similar to alcohol and nicotine. The presence of an addictive chemical might not be crucial for identifying an addiction, as the authors theorize there are many addictive chemicals with the ability to cause addiction in unknown doses and intake levels.

What should be done?

Based on all this, the authors of this analysis propose that ultra-processed foods be classified as addictive substances. They believe this would increase focus on the culpability of manufacturers of these foods, much like how classifying cigarettes as addictive helped combat smoking.

They believe that research should focus on clearly evaluating how complex features of ultra-processed foods combine to increase their addictive potential. That research can then be used to delineate between addictive and non-addictive foods based on those features. Studies should also focus on fully understanding the mechanisms linking the consumption of these foods to obesity and adverse health outcomes.

Tackling food addiction through policies

Authors of the analysis also believe that governments should combat food addiction in the same way they tackled addiction to cigarettes – through a suite of policies targeting foods with high addiction potential, notably ultra-processed foods. Examples of such policies include special taxes on ultra-processed foods and beverages, mandatory or voluntary front-of-pack or shelf labeling systems, and mandatory or voluntary reformulations of the food supply, particularly focused on banning the use of substances, increasing the addictive effects.

However, the authors also note that the consumption of ultra-processed foods tends to be particularly high in disadvantaged neighborhoods because these foods are inexpensive. There is limited if any, availability of lower-calorie, healthier foods in those areas, and those people consume the higher-calorie, ultra-processed foods instead. In light of this fact, tackling the issue of food addiction should be done with care and in a way that does not create food insecurity.

Additionally, including ultra-processed food addiction diagnosis in clinical care would improve access to support and enable the development of treatments to reduce compulsive patterns of ultra-processed food intake. Drugs already exist that show promise in helping overcome food addiction.

Conclusion

Overall, the analysis makes a strong case for the reality of ultra-processed food addiction. The ongoing obesity pandemic (Wong et al., 2022) makes what they say important. The authors propose that researchers focus on fully understanding the mechanisms through which addictive behaviors toward specific foods occur.

They also propose that policymakers approach legislation on food addiction similarly to nicotine, tobacco, and cigarette addiction – through recognizing ultra-processed food addiction as a disorder, through policies targeting the production and the sale of addictive foods, preventing the use of substances or processes that increase the addictiveness of food items, and other measures. Still, this should be done with care and in a way that does not reduce food security for anyone. Ultra-processed foods are still foods, and people need food to survive.

The analysis paper “Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction” was authored by Ashley N. Gearhardt, Nassib B. Bueno, Alexandra G. DiFeliceantonio, Christina A. Roberto, Susana Jimenez-Murcia, and Fernando Fernandez-Aranda.

References

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Gearhardt, A. N., Yokum, S., Orr, P. T., Stice, E., Corbin, W. R., & Brownell, K. D. (2011). Neural Correlates of Food Addiction. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(8), 808–816. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHGENPSYCHIATRY.2011.32

Hedrih, V. (2023). Women Consuming Lots of Artificially Sweetened Beverages Might Have a Higher Risk of Depression, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/women-consuming-lots-of-artificially-sweetened-beverages-might-have-a-higher-risk-of-depression-study-finds/

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. In Public Health Nutrition (Vol. 22, Issue 5, pp. 936–941). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Moubarac, J. C., Levy, R. B., Louzada, M. L. C., & Jaime, P. C. (2018). The un Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutrition, 21(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000234

O’brien, C. P. (2005). Benzodiazepine Use, Abuse, and Dependence. J Clin Psychiatry, 66(2).

Rakić-Bajić, G., & Hedrih, V. (2012). Prekomjerna upotreba interneta, zadovoljstvo životom i osobine ličnosti [Excessive use of the internet, life satisfaction and personality factors]. Suvremena Psihologija, 15(1), 119–131.

Samuthpongtorn, C., Nguyen, L. H., Okereke, O. I., Wang, D. D., Song, M., Chan, A. T., & Mehta, R. S. (2023). Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Network Open, 6(9), e2334770. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34770

Ting, C. H., & Chen, Y. Y. (2020). Smartphone addiction. Adolescent Addiction: Epidemiology, Assessment, and Treatment, 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818626-8.00008-6

Weingarten, H. P., & Elston, D. (1990). The phenomenology of food cravings. Appetite, 15(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(90)90023-2

West, R. (2001). Theories of addiction. Addiction, 96(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1360-0443.2001.96131.X

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005

Leave a comment