Do the Quality and Timing of Your Snacks Affect Your Cardiometabolic Health?

- A study published in the European Journal of Nutrition found that individuals consuming poor-quality snacks tend to have poorer cardiometabolic health indicators

- Individuals snacking late in the evening, after 9 pm, tended to have poorer cardiometabolic health indicators than those not snacking late

- The number of consumed snacks per day was not associated with cardiometabolic health indicator levels

Snacking

Snacking is consuming small, often casual, food portions between regular meals. Individuals typically do this to curb hunger, satisfy cravings, ease stress/boredom/nerves, or provide a quick energy boost. Snacks can vary widely in terms of their nutritional content and may range from healthy options like fruits and nuts to less nutritious choices like chips and candy.

A study in the U.S. indicated that 97% of people practiced snacking in 2006. The same study reported that the share of snack calories in the total daily energy intake stood at 24%. This was a substantial increase compared to findings in previous years. Not only did snacking become more widespread, but the energy density of snacks consumed increased (Piernas & Popkin, 2010). This increase in snacking coincided with the worldwide obesity pandemic (Wong et al., 2022).

A study in the U.S. in 2006 indicated that 97% of people practiced snacking and the share of snack calories in their total daily energy was 24%

Cardiometabolic blood markers

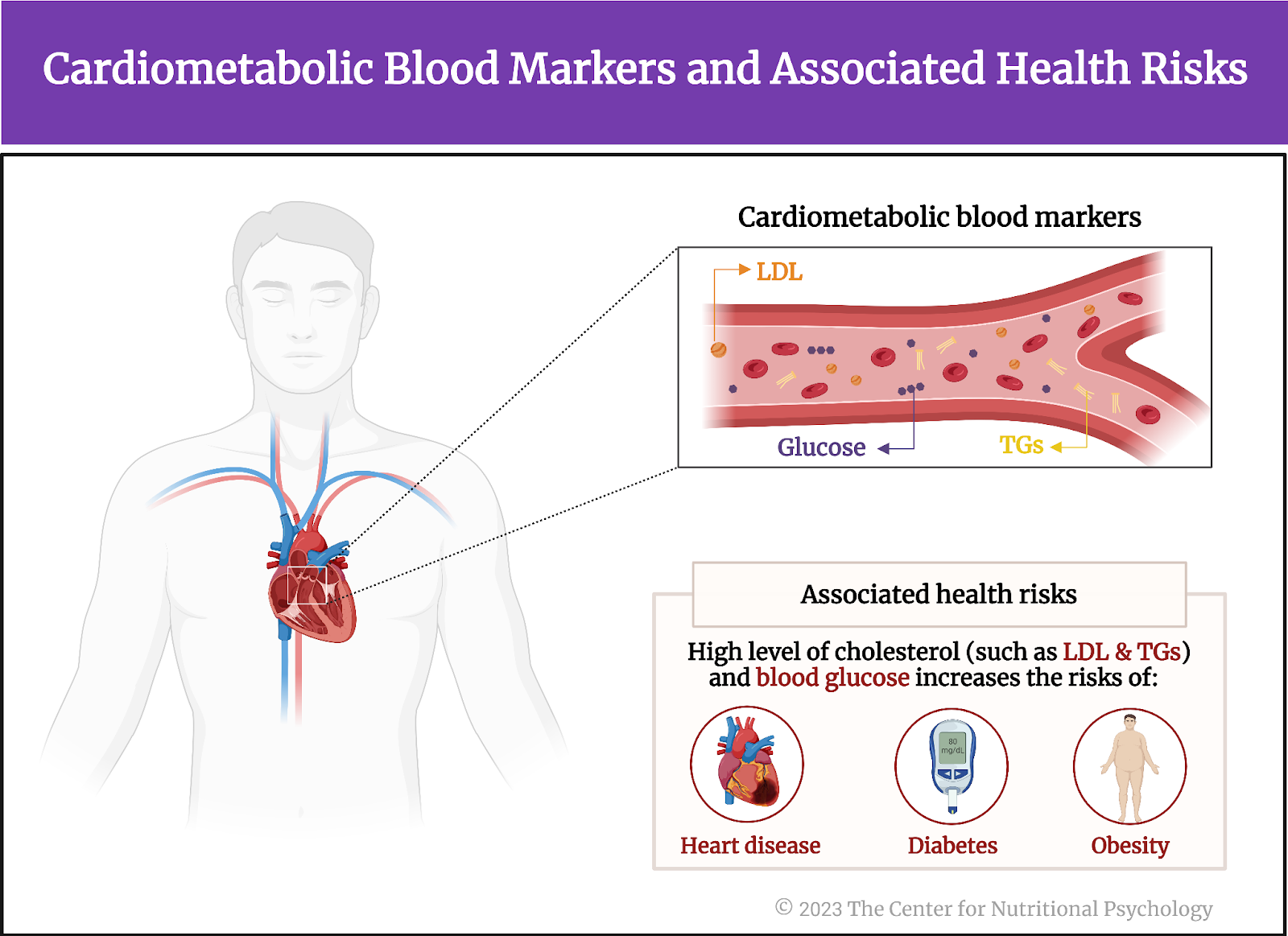

When studying the effects of various dietary patterns or differences between groups of individuals practicing different dietary patterns, researchers rely on various indicators of the functioning of study participants’ metabolisms and various physiological parameters to estimate possible links between dietary patterns and health. One very frequently used group of indicators is cardiometabolic blood markers, a group of indicators that can be derived from a blood sample.

Cardiometabolic blood markers are a group of specific substances found in the bloodstream that provide information about an individual’s cardiovascular and metabolic health. These markers include cholesterol levels, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol), which is associated with an increased risk of heart disease when elevated. Additionally, triglycerides (TGs), a type of fat in the blood, and blood glucose levels are important indicators of metabolic health. Elevated markers can signify an increased risk of diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, making them crucial for assessing and managing overall health and wellness (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cardiometabolic blood markers and associated health risks

Snacking and health

On the general level, snacking can be beneficial for health. It distributes energy and nutrient intake across multiple occasions in a day. Frequent snacks also present more opportunity for an individual to consume specific nutrients required by the body, thereby completing main meals (Marangoni et al., 2019)

On the general level, snacking can be beneficial for health

However, this largely depends on what the snacks are, i.e., their quality. For example, a recent study showed that snacking on a high-quality snack, i.e., whole almonds for six weeks, improved endothelial function, i.e., the ability of a thin layer of cells lining the inner surface of blood vessels to regulate various physiological processes in the cardiovascular system. These snacks also reduced concentrations of LDL cholesterol (also known as “bad“ cholesterol) in the blood (Dikariyanto et al., 2020).

On the other hand, consuming low-quality snacks, snacks consisting of ultra-processed foods, and foods with poor nutritional values can have opposite effects. Studies have linked frequent consumption of ultra-processed foods to adverse health outcomes (Monteiro et al., 2019; Samuthpongtorn et al., 2023), and it makes little difference whether these foods are perceived as snacks or as the main meals.

Frequent consumption of ultra-processed foods leads to adverse health outcomes

The current study

Study author Kate M. Bermingham and her colleagues wanted to explore the relationship between snacking habits – frequency of snacks, their quality, and timing with cardiometabolic blood markers, body measures, and the gut microbiome. They analyzed data from the ZOE PREDICT 1 study.

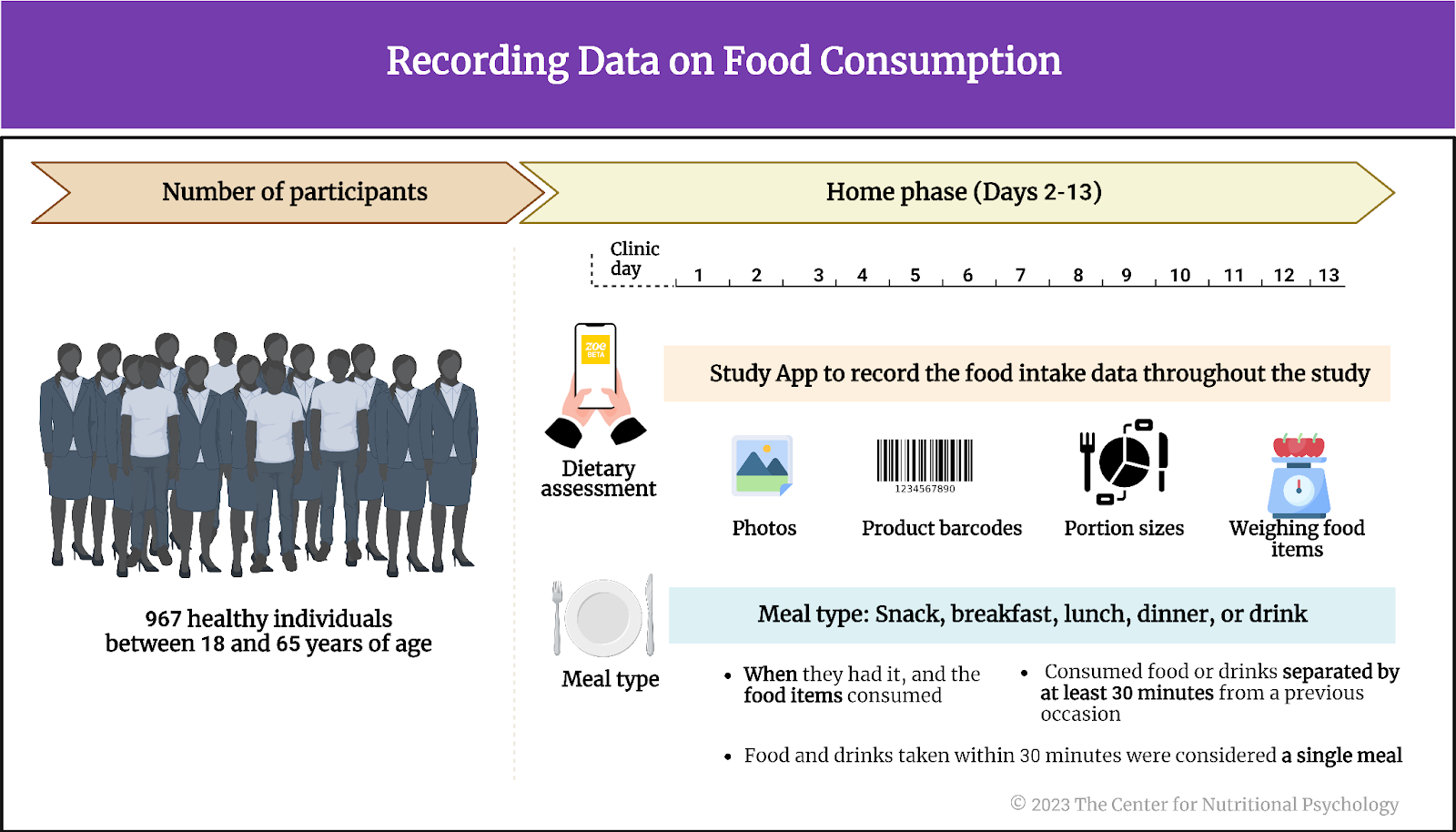

ZOE PREDICT 1 was a diet intervention study conducted between June 2018 and May 2019 that examined interactions between diet and cardiometabolic markers. The study participants were 967 healthy individuals from the UK. They were between 18 and 65 years of age. 73% of the participants were females. The study lasted for two weeks. Participants visited the clinic on the first day to take measurements and logged their dietary behavior for the next 13 days.

Participants logged food intake through an app

Researchers running the ZOE PREDICT 1 study trained study participants to accurately record their food intake using photos, product barcodes, portion sizes, and weighing food items on digital scales. Participants used a specially developed app called ZOE to record their food intake data throughout the study. Researchers collected data on the nutrient compositions of food from a nutrient database, while data on the contents of branded food items came from supermarket websites.

Participants reported the meal type (i.e., snack, breakfast, lunch, dinner, or drink), when they had it, and the food items consumed. A meal was when a participant consumed food or drinks separated by at least 30 minutes from a previous occasion. All food and drinks taken within 30 minutes of each other were considered a single meal. Participants consumed standardized meals on multiple study days to allow researchers to test their effects, but data from those days were not included in these analyses (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Recording data on food consumption

Snacking habits and other data

Study authors considered snacks to be food or drinks consumed between main meals. They could consist of a single or multiple types of foods. However, the study authors did not count drinks of up to 50 kcal (e.g., drinking a glass of water) as snacks (if nothing else was consumed along with those drinks).

From the snacking data, researchers assessed the quality of snacks and inferred typical consumption times. The quality of snacks was related to the level of processing. Poor-quality snacks were ultra-processed, while unprocessed or minimally processed foods were considered high-quality.

Participants reported their hunger levels daily through the ZOE app. They did this at the time of the first logging into the app of the day and at regular intervals later. There were up to 7 hunger ratings per day. Participants also self-reported their general activity levels over the past year (“In the past year, how frequently have you typically engaged in physical exercises that raise your heart rate and last for 20 min at a time?”). They provided stool samples to allow researchers to examine their gut microbiome composition and gave blood samples at the start of the study for measuring cardiometabolic markers.

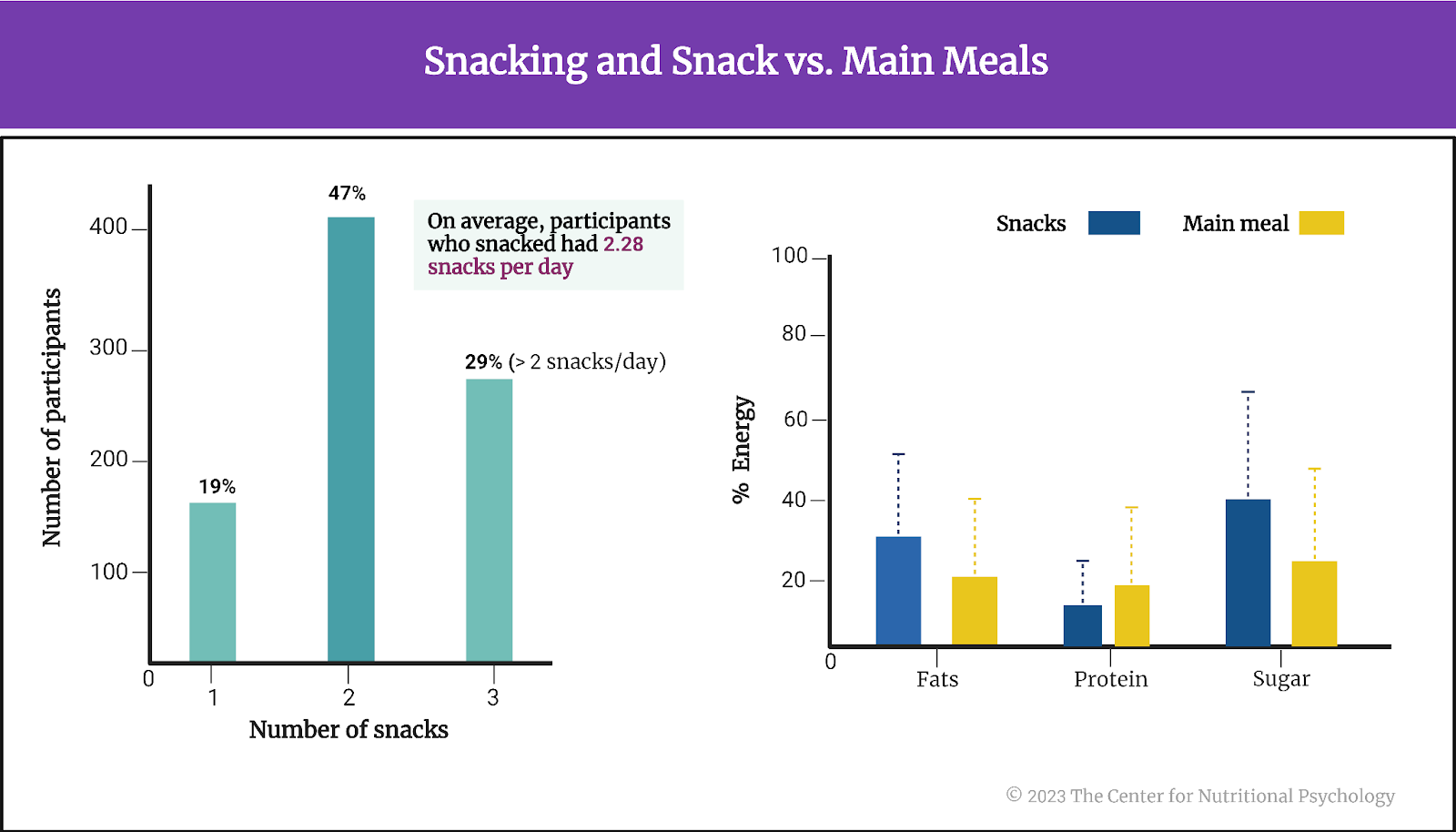

People who snack have 2.28 snacks per day on average

Results showed that 95% of participants snacked. On average, participants who snacked had 2.28 snacks per day: 19% had one snack per day, 47% had two snacks/day, and 29% had more than 2. The more snacks an individual had, the higher the share of snacks in their total daily energy intake was. Participants with larger shares of sugar and fats in their diets tended to consume more daily snacks, and their snacks tended to be higher in energy. Compared to main meals, snacks had higher shares of fats and sugars but lower protein contents (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Snacking and snack vs. main meals

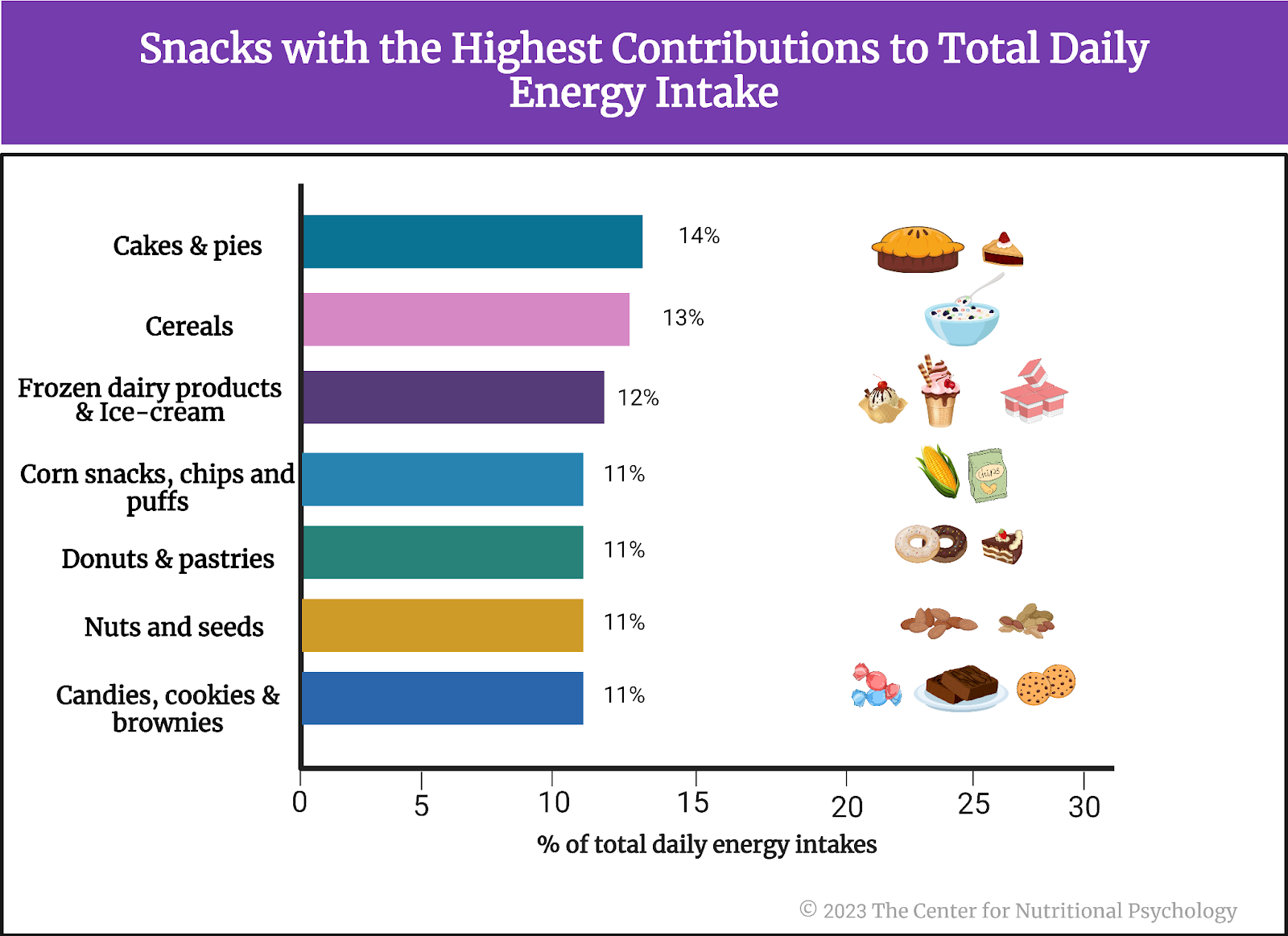

Cakes, pies, cereals, and ice cream were snacks with the highest contribution to energy intake

The most popular foods consumed as snacks were drinks (milk, tea, coffee, fruit drinks), candy, cookies and brownies, nuts, seeds and fruits (apples, bananas, citrus fruits), crisps, bread, cheese and butter, cakes and pies, and granola or cereal bars.

However, snacks with the highest contributions to total daily energy intakes were cakes and pies (14% of energy intake), cereals (13%), ice cream and frozen dairy products (12%), donuts and pastries (11%), candies, cookies and brownies (11%), nuts and seeds (11%) and corn snacks, chips and puffs (11%). There were no differences between genders on the average share of energy derived from snacks. The same was true with different age groups and people with different overall physical activity levels (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Snacks with the highest contributions to total daily energy intake

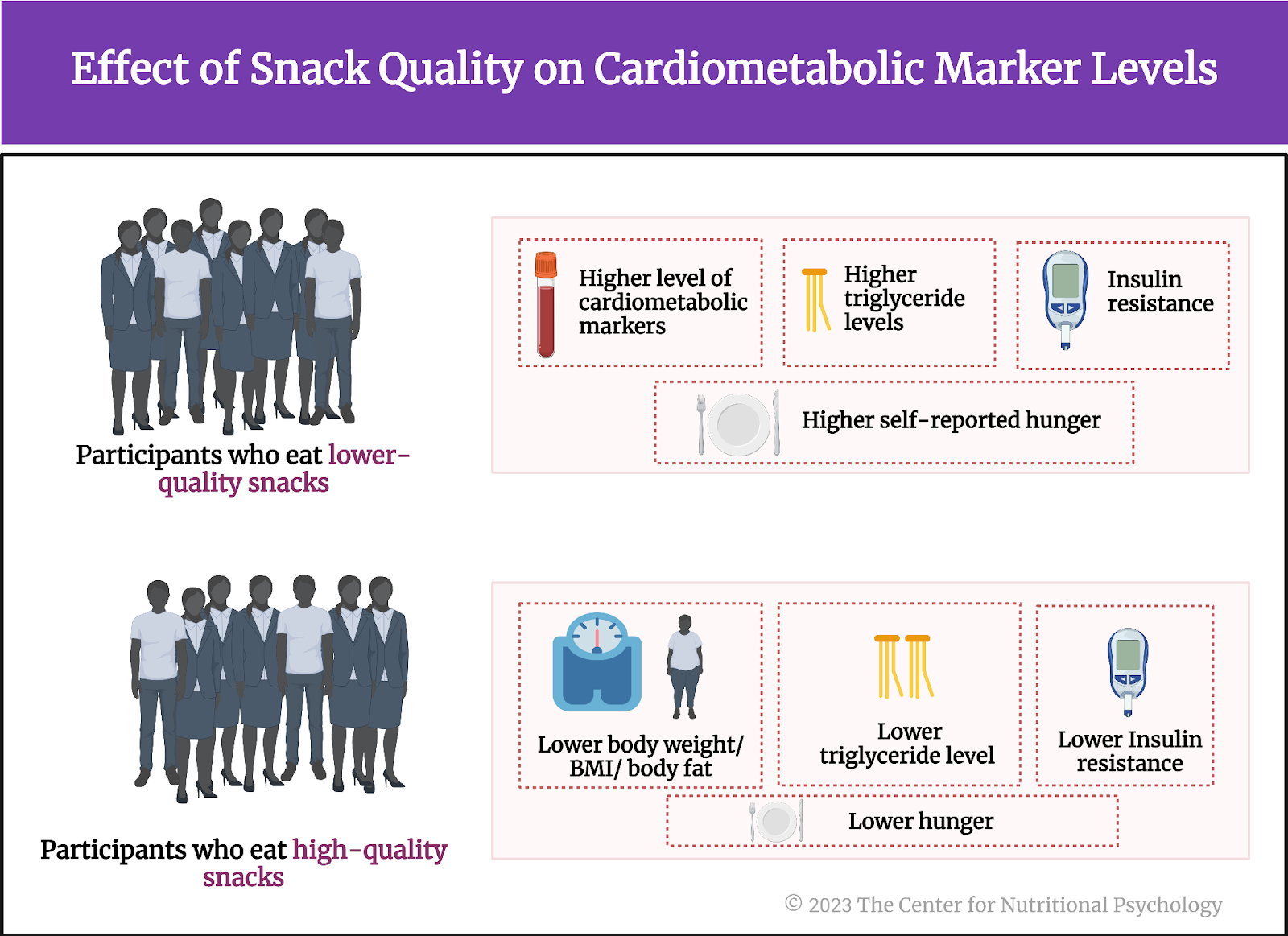

People who eat better-quality snacks tend to have more favorable cardiometabolic blood marker levels

There were no differences in cardiometabolic blood marker levels between people who ate different numbers of snacks per day, nor between those who ate and those who did not eat snacks. There was also no association between the quantity of energy derived from snacks and cardiometabolic marker levels. Gut microbiota composition was not associated with snacking habits.

The number of snacks in a day and the quantity of energy derived from them were not associated with cardiometabolic blood markers (the quality of snacks was)

However, the quality of snacks was associated with cardiometabolic marker levels. Analysis showed that, on average, individuals who eat lower-quality snacks have higher levels of cardiometabolic markers than those who eat better-quality snacks. More specifically, these individuals had higher triglyceride levels and were more likely to show insulin resistance. They also had higher average levels of self-reported hunger. Participants eating high-quality snacks tended to have lower body weight, body mass index values, and body fat (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effect of snack quality on cardiometabolic marker levels

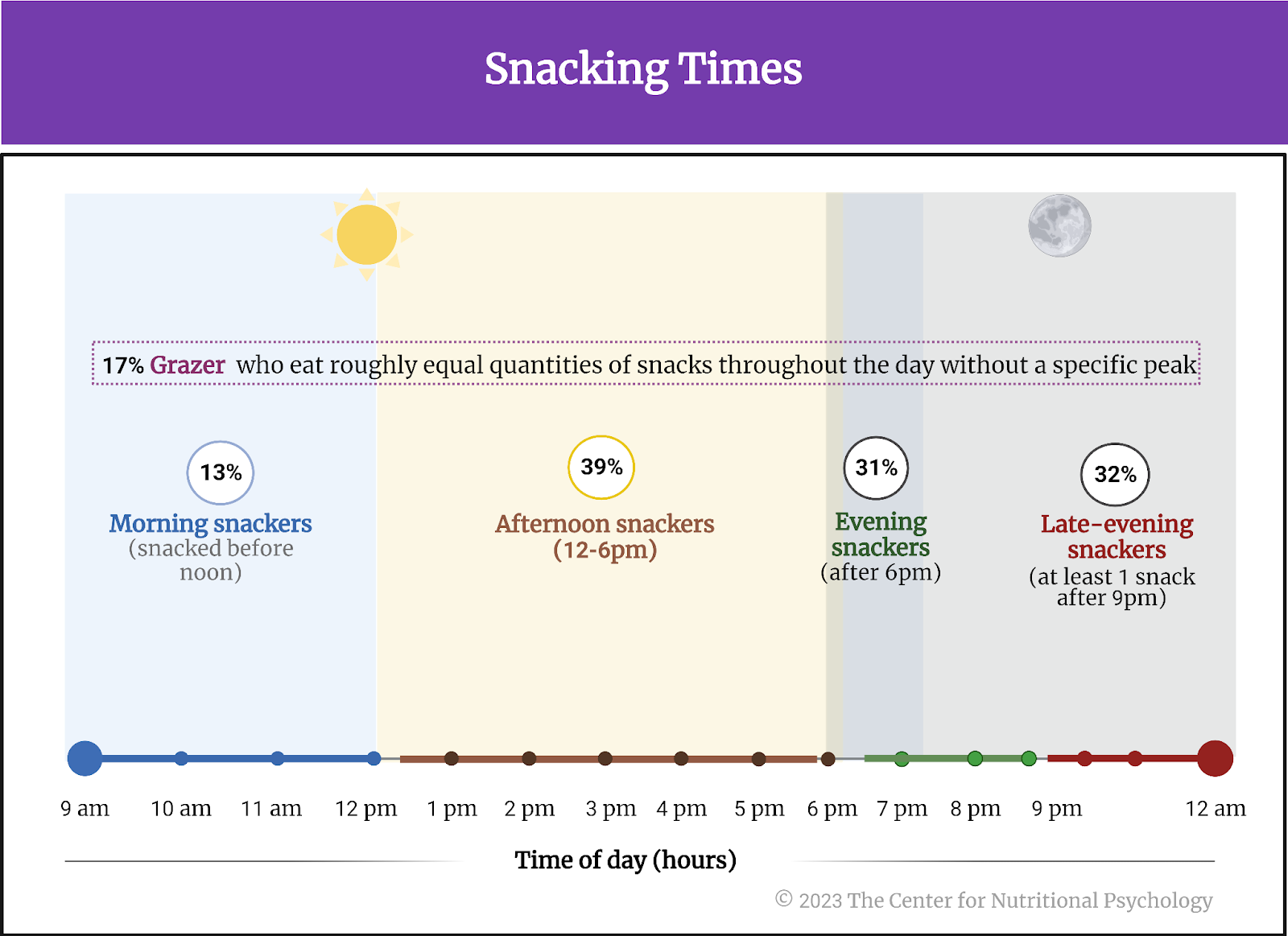

Late-evening snackers had poorer cardiometabolic blood marker levels

Analysis of the time of snack consumption showed that 13% of participants tended to mostly snack before noon (up to 50% of calories from snacks in that period), 39% were afternoon snackers (12 pm – 6 pm), and 31% were evening snackers (after 6 pm). 17% ate snacks equally throughout the day – there was no specific period when they ate more snacks. Additionally, researchers found that 32% of individuals tend to eat snacks (at least one) late in the evening – after 9 p.m. They referred to these individuals as late-evening snackers (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Snacking times

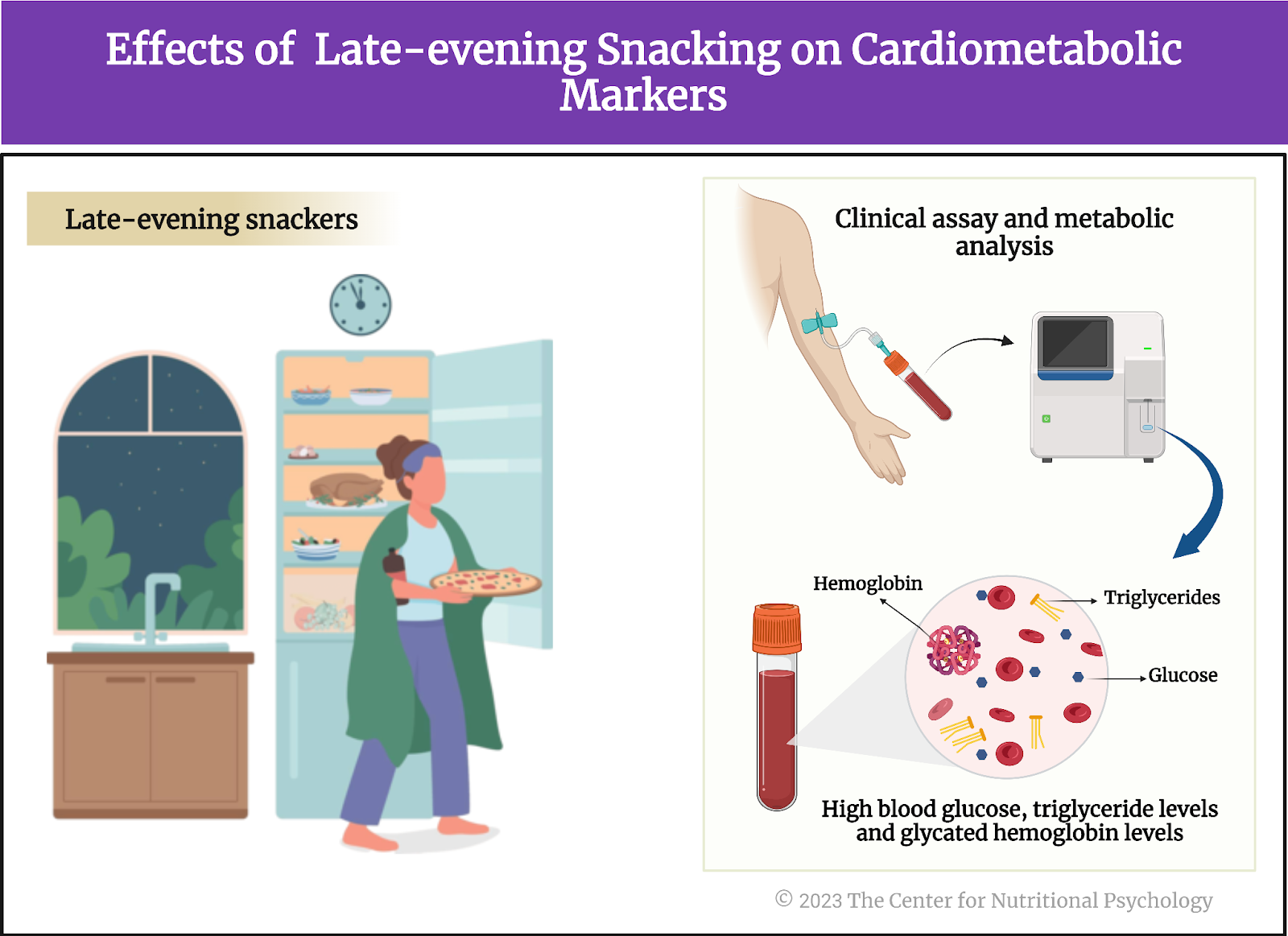

Statistical analyses showed that late-evening snackers tend to have poorer cardiometabolic marker levels than those who do not snack after 9 p.m. Notably, these individuals had heightened blood glucose and triglyceride levels after meals and higher glycated hemoglobin levels compared to those who ate their snacks during the day. These differences were even higher in late-evening snackers prone to consuming poor-quality snacks (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effect of late-evening snacking on cardiometabolic markers

Conclusion

The study showed that the number of snacks eaten throughout the day is not associated with cardiometabolic blood marker levels. The same was the case with the share of energy derived from snacks. However, these health indicators are related to the quality of snacks and the time of day consumed. Consuming poor-quality snacks, particularly late in the evening, was associated with poorer cardiometabolic health indicators.

These findings could be used to inform the general public, as well as metabolic and cardiovascular disease prevention programs, about the possible health effects of snacking habits. Although the study design does not allow any cause-and-effect conclusions to be drawn, i.e., it remains unknown whether changing snacking habits would affect cardiometabolic indicator levels, there is a possibility that simply switching to better-quality snacks and avoiding late-evening snacking might indeed improve cardiometabolic health indicators and reduce the risk of serious metabolic diseases by at least some extent.

The paper “Snack quality and snack timing are associated with cardiometabolic blood markers: the ZOE PREDICT study” was authored by Kate M. Bermingham, Anna May, Francesco Asnicar, Joan Capdevila, Emily R. Leeming, Paul W. Franks, Ana M. Valdes, Jonathan Wolf, George Hadjigeorgiou, Linda M. Delahanty, Nicola Segata, Tim D. Spector, and Sarah E. Berry.

References

Bermingham, K. M., May, A., Asnicar, F., Capdevila, J., Leeming, E. R., Franks, P. W., Valdes, A. M., Wolf, J., Hadjigeorgiou, G., Delahanty, L. M., Segata, N., Spector, T. D., & Berry, S. E. (2023). Snack quality and snack timing are associated with cardiometabolic blood markers: the ZOE PREDICT study. European Journal of Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03241-6

Dikariyanto, V., Smith, L., Francis, L., Robertson, M., Kusaslan, E., O’Callaghan-Latham, M., Palanche, C., D’Annibale, M., Christodoulou, D., Basty, N., Whitcher, B., Shuaib, H., Charles-Edwards, G., Chowienczyk, P. J., Ellis, P. R., Berry, S. E. E., & Hall, W. L. (2020). Snacking on whole almonds for 6 weeks improves endothelial function and lowers LDL cholesterol but does not affect liver fat and other cardiometabolic risk factors in healthy adults: the ATTIS study, a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 111(6), 1178–1189. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAA100

Marangoni, F., Martini, D., Scaglioni, S., Sculati, M., Donini, L. M., Leonardi, F., Agostoni, C., Castelnuovo, G., Ferrara, N., Ghiselli, A., Giampietro, M., Maffeis, C., Porrini, M., Barbi, B., & Poli, A. (2019). Snacking in nutrition and health. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 70(8), 909–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2019.1595543

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. In Public Health Nutrition (Vol. 22, Issue 5, pp. 936–941). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Piernas, C., & Popkin, B. M. (2010). Snacking Increased among U.S. Adults between 1977 and 2006, ,. The Journal of Nutrition, 140(2), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.3945/JN.109.112763

Samuthpongtorn, C., Nguyen, L. H., Okereke, O. I., Wang, D. D., Song, M., Chan, A. T., & Mehta, R. S. (2023). Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Network Open, 6(9), e2334770. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34770

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005

Leave a comment