- A conceptual paper published in the Journal of Metabolic Health proposes that there are five stages of addiction to ultra-processed foods.

- In the first, pre-addiction stage, consumption of sugar and fat leads to increased activity in the regions of the brain responsible for reward experiences, and people pay more attention to hyperpalatable foods.

- In the final stage, the functioning of these centers is severely disrupted with very low activity and depletion of key neuromodulators, while eating becomes compulsive, and all control is lost.

Substance addictions are a big problem in the modern world. Addiction to nicotine (most often in the form of tobacco) is the most common (Tobacco, 2025), but there are also large numbers of people addicted to alcohol and drugs. The thing in common for all these people is that they have started using those substances because their use gave them pleasure. However, in time, the pleasure faded away, but the craving for those substances increased. They needed more and more, and started experiencing serious discomfort when they could not use them. Many affected individuals started neglecting their major roles in life (e.g., jobs, significant others), focusing on obtaining and using the substance (taking drugs, being drunk, spending scarce money on tobacco…). Many repeatedly tried to quit but failed.

While these addictions are well-known, scientists recently proposed that people can also become addicted to specific types of food.

Food addiction

From the very start, the idea that food can be addictive has been seen as controversial by many (Tarman, 2024). On the one hand, humans need food to survive. Without food, our bodies would starve and die relatively quickly. Given this, it is entirely understandable that people attach great importance to having access to sufficient food and being able to eat regularly.

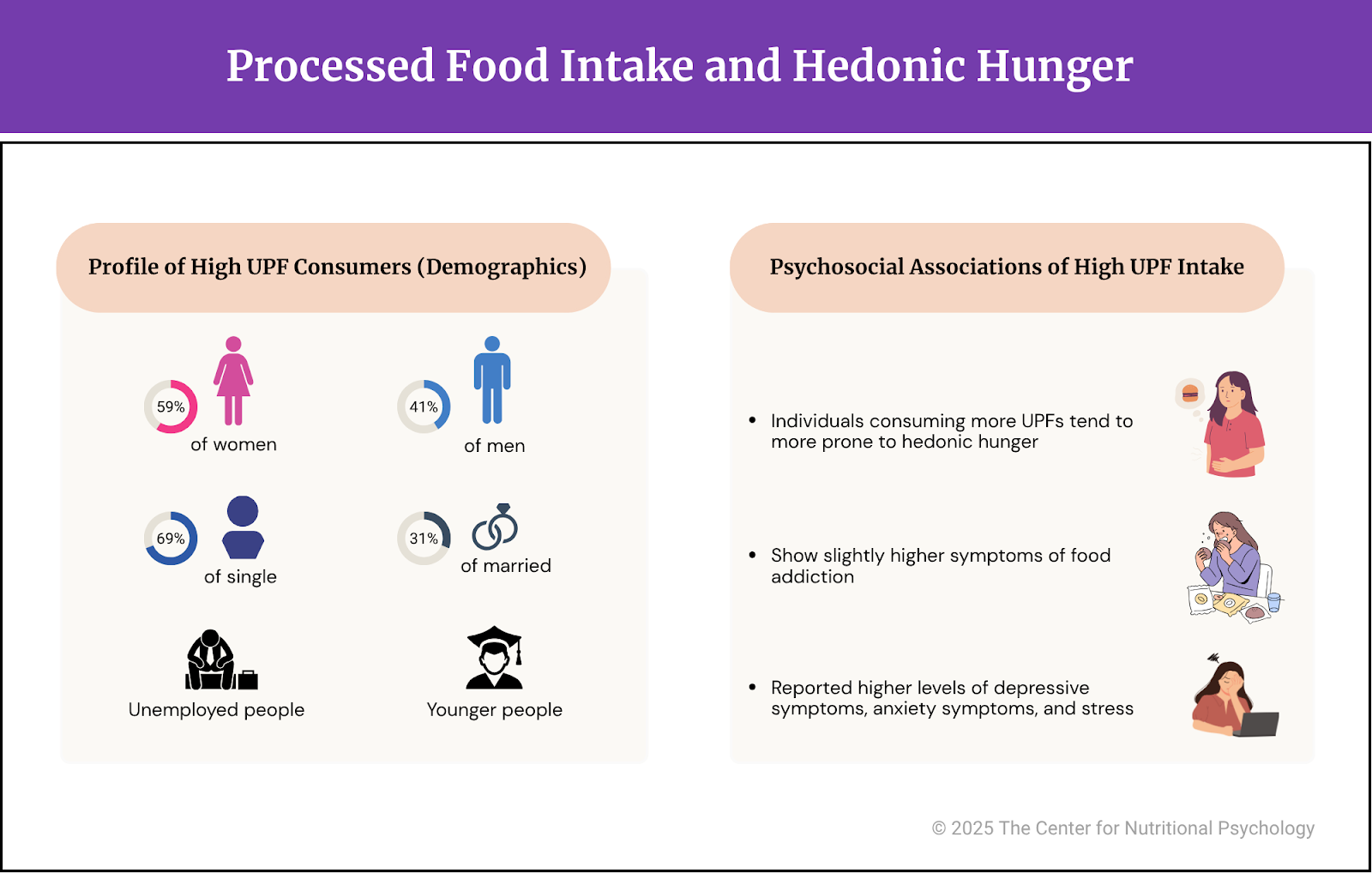

On the other hand, people also eat when their bodies do not need the intake of nutrients. This desire to eat that is not driven by the need for nutrients is referred to as hedonic hunger (Lowe & Butryn, 2007). Eating motivated by food cues and factors that do not represent the body’s need for nutrients is called external eating (Van Strien et al., 1986).

The rewarding effects of food and developing food addiction

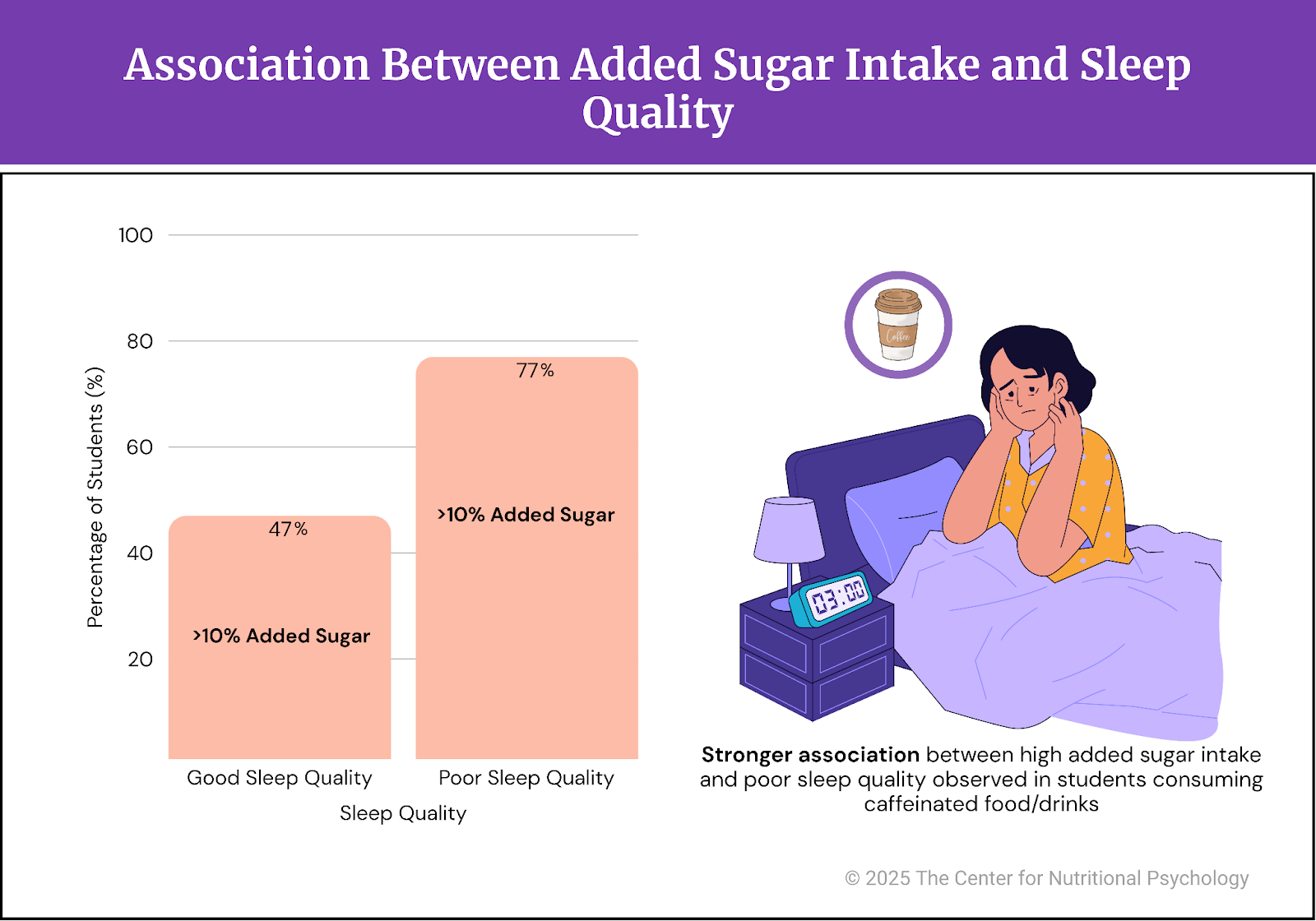

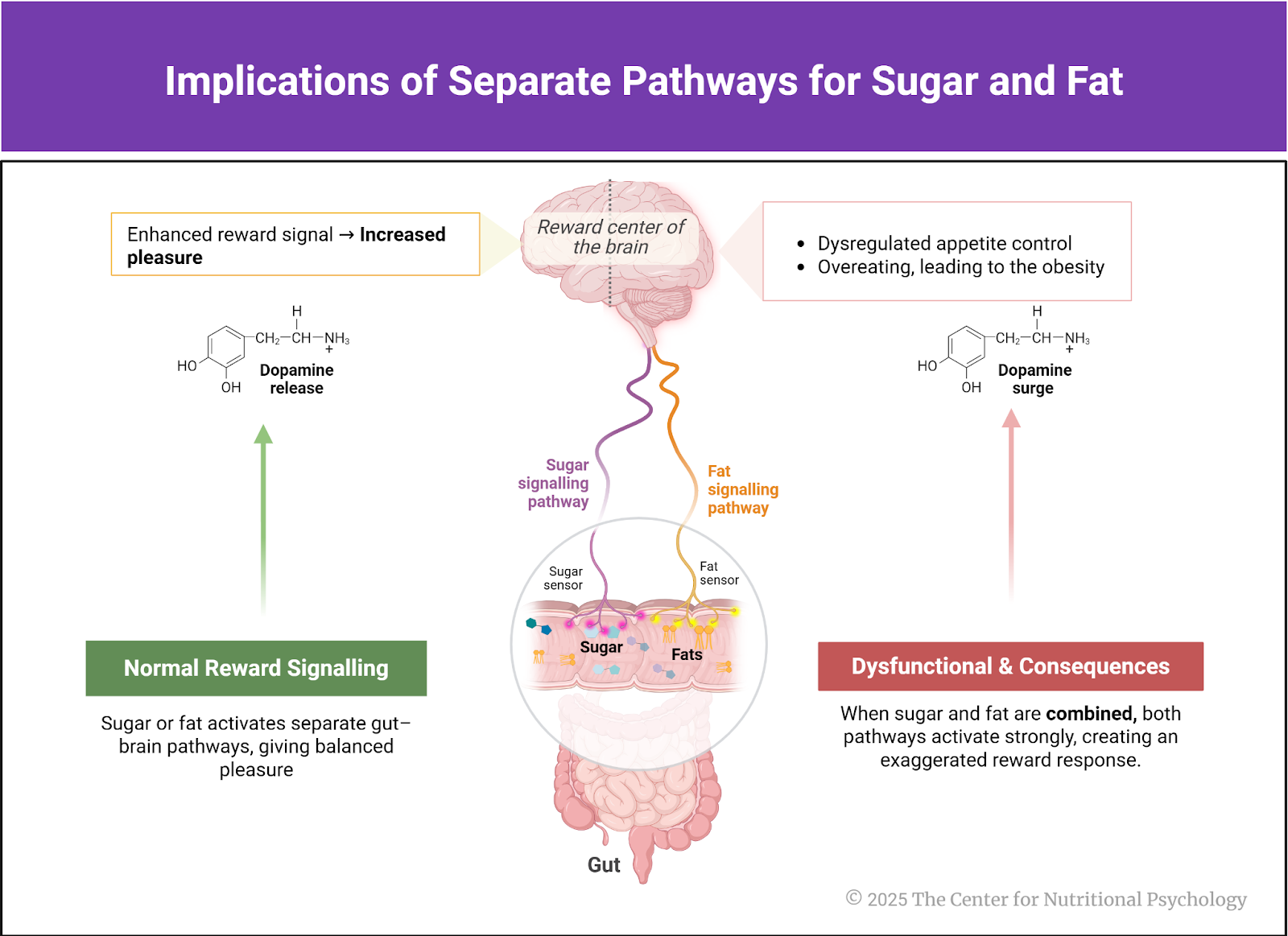

Eating food can be a rewarding experience, particularly when the food tastes good. Studies have shown that our bodies have signaling pathways connecting the digestive system to the reward areas of the brain (McDougle et al., 2024). The presence of fat and sugar triggers the activity of these pathways. When they detect the presence of fat or sugar in the gut, they send signals to the reward areas of the brain, producing the experience of pleasure.

Our bodies have signaling pathways linking our digestive system to the reward areas of the brain.

The pathways for sugar and fat are separate (McDougle et al., 2024). This means that when both fat and sugar enter our digestive system, both sets of pathways start signaling, greatly increasing the feelings of reward. That is the reason why we find foods rich in easily digestible fats and sugars so tasty.

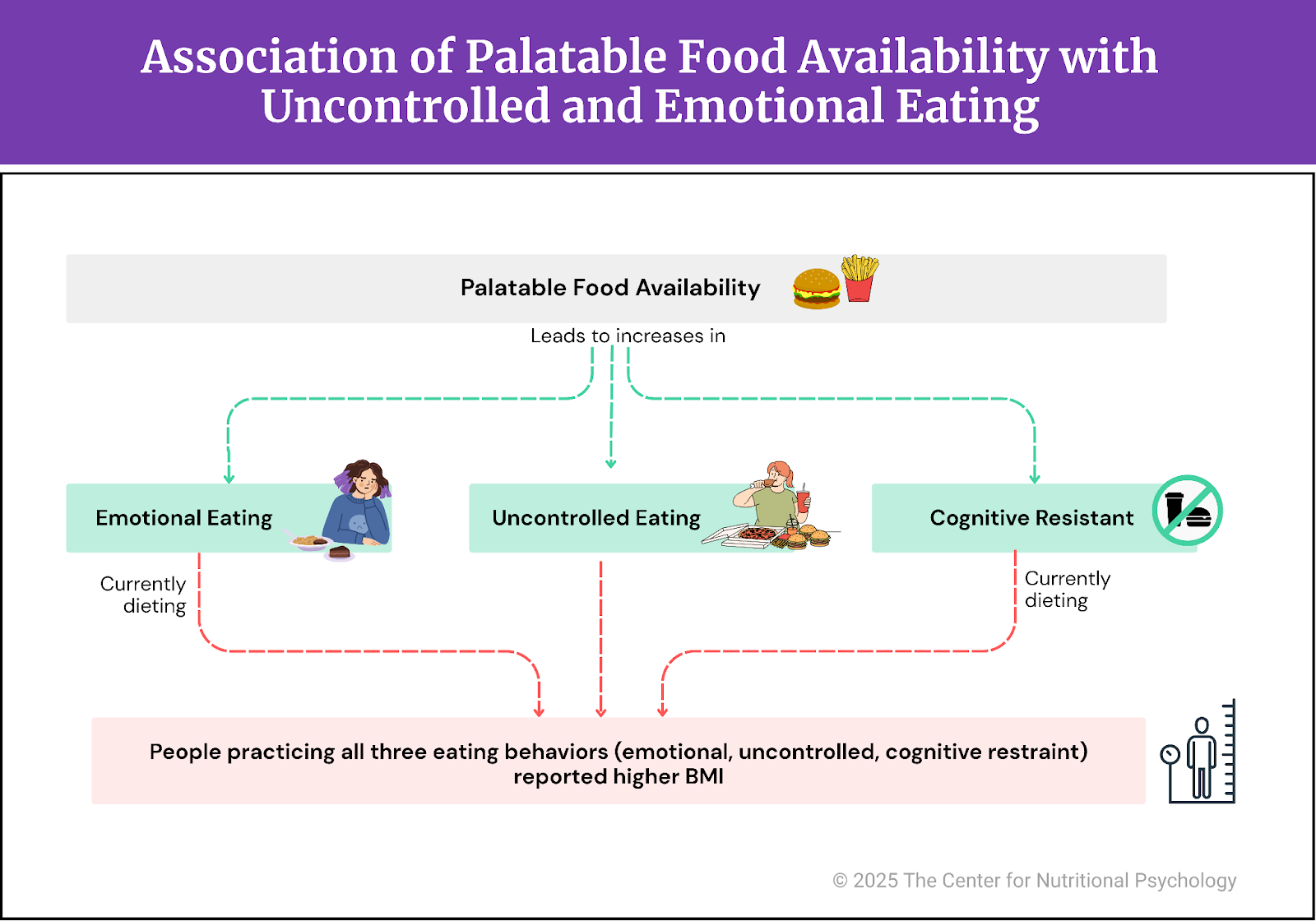

However, research indicates that triggering these reward areas so intensely often tends to dysregulate them, disrupting the body’s control system for food intake and regulation. This will promote overeating and can lead to obesity (see Figure 1). Studies on rodents have shown that feeding them diets rich in easily digestible fats and sugars is a reliable way to induce obesity (Hedrih, 2024; Ikemoto et al., 1996; Loxton, 2018).

Figure 1. Implications of separate pathways for sugar and fat

Studies on rodents show that feeding them diets rich in easily digestible fats and sugars is a sure way to make them obese.

In the long term, disruptions created in this way can produce symptoms similar to those seen in substance addiction (Fletcher & Kenny, 2018; Gordon et al., 2018). Some scientists propose that this be called food addiction and classified as a serious mental health disorder. Estimates state that around 14% of people worldwide display symptoms of food addiction (Gearhardt et al., 2023). The development of food addiction is often attributed to ultra-processed foods, which are industrially produced and primarily composed of refined ingredients, additives, and flavors, with little to no intact whole foods (Monteiro et al., 2019).

The five stages of food addiction

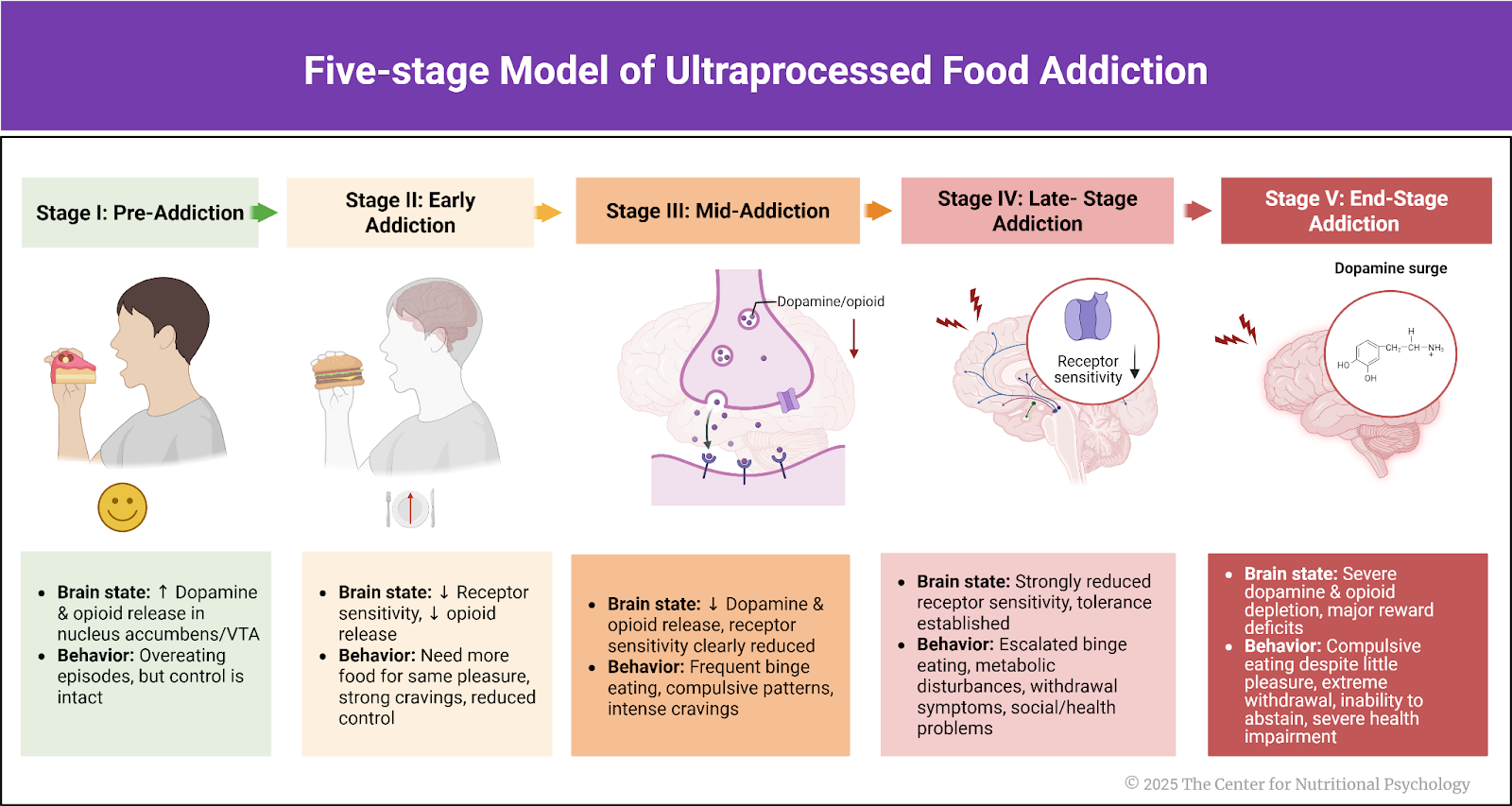

Vera I. Torman is one of the authors who supports the idea that people can become addicted to certain types of food, particularly to ultraprocessed foods. She proposed a model of food addiction development that consists of 5 stages: (1) pre-addiction, (2) early addiction, (3) mid-addiction, (4) late-stage, and (5) end-stage food addiction (Tarman, 2024). The progression through these stages is marked by increasingly greater dysregulation of the brain systems involved in food intake control and corresponding deterioration in food intake behaviors.

According to this model, in the first stage (pre-addiction), consumption of sugar and fat (at the same time) leads to increased activity in the reward regions of the brain, such as the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Signaling in the brain, facilitated by the neurotransmitter dopamine, is increased, as is the release of opioids, substances that modulate the behavior of neural cells. This makes people value foods that produce these rewarding experiences more. People also start paying more attention to such food and to anything associated with it (places, people, brands…). Over time, receptors in neural cells in those areas begin to become less sensitive. People in this phase may engage in overeating episodes, but they do not lose control over their eating behavior.

In the early addiction stage, receptors in the reward areas of the brain become less sensitive to rewards stemming from the intake of highly palatable foods. The release of opioids starts to decrease. People need to eat more to feel the same amount of pleasure. Excessive eating starts, accompanied by strong cravings for food and a lack of control over consumption.

In the third, middle-stage addiction, the sensitivity of receptors (for the neurotransmitter dopamine) in the reward areas is clearly reduced. Release of the neurotransmitter dopamine and opioids is also reduced. Individuals start losing control over their eating behaviors. Binge eating episodes become frequent, individuals experience intense food cravings, and show signs of compulsive eating behaviors.

In a late-stage addiction, the fourth stage, sensitivity of receptors in the reward areas of the brain is further reduced, and so is the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine and brain opioids. Tolerance develops as individuals require more food to achieve the same level of pleasurable experiences. Binge eating escalates, and cognitive control over eating behaviors is mostly lost. Affected individuals experience metabolic disturbances. Withdrawal symptoms become more intense when they try to reduce food intake. It is at this point that affected individuals lose their jobs, their relationships become strained, and their health issues become prominent.

In the final, end-stage addiction, the brain reward system deficits are very pronounced, and the release of dopamine and opioids in these areas is extremely low due to depletion (see Figure 2). Metabolic derangements are significant, and the executive functions of affected individuals are grossly impaired. Food consumption is compulsive despite minimal pleasure or rewards from eating. It occurs completely without control. The person cannot abstain from overeating and binge eating without experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms.

Figure 2. Five-stage model of ultraprocessed food addiction

Conclusion

The five-stage model of ultraprocessed food addiction describes the changes in behaviors and brain physiology of affected individuals as food addiction progresses. This model can be used in treating food addiction to tailor interventions to the stage of addiction the person is in.

The author of this model believes that in the early stages, interventions aimed at increasing inhibitory control and addressing any hormonal imbalances may be sufficient. However, more intensive interventions might be necessary in the middle and later stages of food addiction.

The paper “One size does not fit all: Understanding the five stages of ultra-processed food addiction” was authored by Vera I. Tarman.

Find out more about ultra-processed foods and their effect on psychological health and eating behavior in the Nutritional Psychology Research Library “Sugar, Ultra-processed Foods and Mental Health” Research Category. CNP is developing the field of nutritional psychology, one study at a time.

References

Fletcher, P. C., & Kenny, P. J. (2018). Food addiction: A valid concept? Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(13), 2506–2513. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0203-9

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Gordon, E. L., Ariel-Donges, A. H., Bauman, V., & Merlo, L. J. (2018). What Is the Evidence for “Food Addiction?” A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 10(4), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040477

Hedrih, V. (2024, February 19). Consuming Fat and Sugar (At The Same Time) Promotes Overeating, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/16563-2/

Ikemoto, S., Takahashi, M., Tsunoda, N., Maruyama, K., Itakura, H., & Ezaki, O. (1996). High-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and obesity in mice: Differential effects of dietary oils. Metabolism, 45(12), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90185-7

Lowe, M. R., & Butryn, M. L. (2007). Hedonic hunger: A new dimension of appetite? Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.006

Loxton, N. J. (2018). The Role of Reward Sensitivity and Impulsivity in Overeating and Food Addiction. Current Addiction Reports, 5(2), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0206-y

McDougle, M., de Araujo, A., Singh, A., Yang, M., Braga, I., Paille, V., Mendez-Hernandez, R., Vergara, M., Woodie, L. N., Gour, A., Sharma, A., Urs, N., Warren, B., & de Lartigue, G. (2024). Separate gut-brain circuits for fat and sugar reinforcement combine to promote overeating. Cell Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.014

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Tarman, V. I. (2024). One size does not fit all: Understanding the five stages of ultra-processed food addiction. Journal of Metabolic Health, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/jmh.v7i1.90

Tobacco. (2025). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

Van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E. R., Bergers, G. P. A., & Defares, P. B. (1986). The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(2), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2%253C295::AID-EAT2260050209%253E3.0.CO;2-T