The Western Diet and How it Weakens the Interoceptive Signals that Control our Appetitive Behavior

In terms of the global dietary landscape, the Western diet provides a rich diversity and abundance of highly processed foods and beverages that are easy to consume. Although highly palatable, this availability also provides us with a steady stream of external cues that can heighten feeding behaviors. Obesogenic environments (those prevalent with cues that promote excessive weight gain) are pervasive across Western societies and are hypothesized to overwhelm the internal cues that normally regulate our dietary intake (Sample et al., 2016).

Obesogenic environments (those prevalent with cues that promote excessive weight gain) are pervasive across Western societies and are hypothesized to overwhelm the internal cues that normally regulate our dietary intake.

These internal cues, which are perceived by the brain through neural circuits in a process known as interoception, are critical in maintaining proper appetites and, ultimately, a healthy physical and mental body. Interoception refers to the process of identifying and listening to internal bodily signals, which may be a modifiable determinant of appetite regulation and weight gain (Robinson et al., 2018). Research is exploring the mechanisms by which interoceptive sensations mediate our nutritional health.

Interoception: our body’s communication network to eating regulation

Interoception is considered one of the six foundational elements within nutritional psychology and is defined as “our internal awareness of the body’s state.” Encompassing conscious and subconscious physiological signals, we sense a variety of internal cues that inform our brain about our heartbeat, breathing, and hunger. A growling stomach, a desire for certain foods, fatigue from a lack of food, and even emotions associated with eating are all examples of internal sensations that can further drive feeding and appetitive behaviors.

The study of interoception is increasing in the field of neuroscience, and there is compelling evidence demonstrating the links between awareness of one’s internal state (called interoceptive awareness) and the regulation of emotion (Price & Hooven, 2018).

Considering the diet-mental health relationship (DMHR), the regulation of food intake—and, perhaps, bodyweight—partially depends on the brain’s capability to respond to internal physiological signals arising from external food-related cues in our environment (Sample et al., 2016). In other words, the ability of environmental food cues to evoke appetitive and dietary intake behavior is held in check by interoceptive satiety signals that inhibit those behaviors (Sample et al., 2016).

There is compelling evidence demonstrating the links between awareness of one’s internal state (called interoceptive awareness) and the regulation of emotion.

Western diets impair the interoceptive signals that control our eating.

In this 2016 study, Sample and her colleagues conducted experiments to investigate how food-related external cues may overwhelm interoceptive internal cues that normally regulate dietary intake. They hypothesized that food-related external cues could promote overeating by attenuating the brain’s hippocampal function, which processes interoceptive satiety signals.

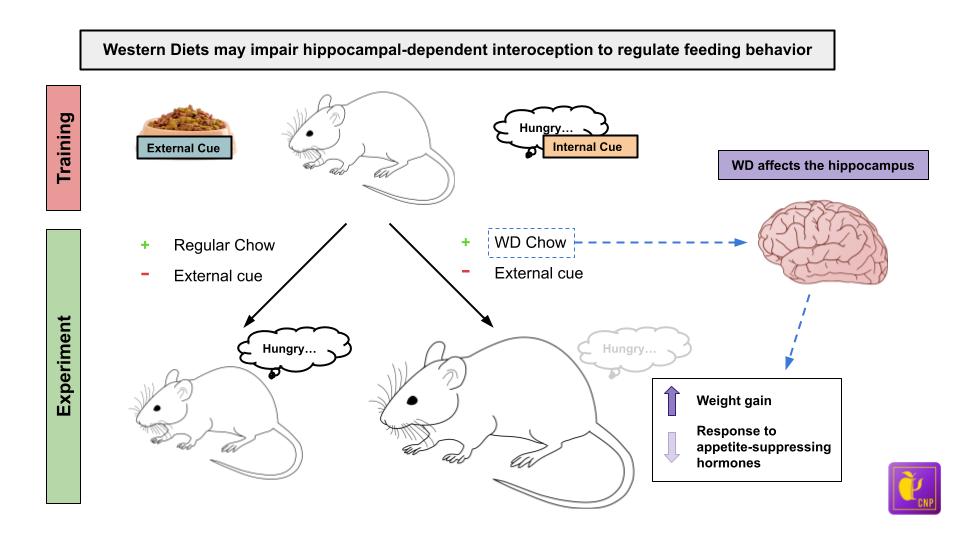

The authors examined the role of a Western diet (WD) (consisting of highly processed, low nutrient foods) and its obesogenic effect on the internal sensations that mediate our appetite. Rodents were trained to use internal cues (i.e., feelings of hunger) and external cues (i.e., food) and then assigned to two distinct groups: a regular chow or WD chow. Both groups then removed external cues to assess the different diets’ direct impact on interoceptive signals that mediate feeding. Interestingly, the study found that the WD group failed to distinguish between internal and external cues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Western diets (WD) impact the internal interoceptive signals used by the hippocampus to regulate appetite and dietary intake. The positive sign indicates the addition of either regular or WD food and the negative sign indicates the removal of food-related external cues.

The inability to parse between interoceptive deprivation (i.e. “I am hungry”) and external signals (i.e. “the food looks delicious”) is a function that has been characterized by the hippocampus, with previous studies demonstrating how the WD could interfere with homeostatic feeding behaviors (Jacka, 2015; Attuquayefio, 2016; Stevenson, 2020).

Indeed, the authors noticed that inhibiting the hippocampus (through surgical injections of a neurotoxin) in a cohort of rodents led to increased weight gain and reduced sensitivity to satiety hormones like cholecystokinin, which normally tells the body you are full and slows digestion (Figure 1). Ultimately, the study suggests that the WD impairs the interoceptive energy state signals that the hippocampus relies on to regulate feeding behavior.

Current research further validates this connection. In a recent study by Robinson, Marty, Higgs, and Jones (2022) exploring the connection between interoception, eating behavior, and body weight in over a thousand human adults, these researchers found that poorer self-reported ability to detect interoceptive signals (deficits in interoceptive accuracy) was, in fact, predictive of higher BMI.

The findings are certainly food for thought as we navigate the choices of food available to us in our day-to-day lives—especially for those living in regions characterized by a high intake of the Western diet. Knowing the options and alternatives of nutritious foods is essential to maintaining proper feeding behaviors that will keep one healthy.

References

Attuquayefio, T., Stevenson, R. J., Boakes, R. A., Oaten, M. J., Yeomans, M. R., Mahmut, M., & Francis, H. M. (2016). A high-fat high-sugar diet predicts poorer hippocampal-related memory and a reduced ability to suppress wanting under satiety. Journal of experimental psychology. Animal learning and cognition, 42(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/xan0000118

Jacka, F. N., Cherbuin, N., Anstey, K. J., Sachdev, P., & Butterworth, P. (2015). Western diet is associated with a smaller hippocampus: a longitudinal investigation. BMC medicine, 13, 215. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0461-x

Price, C. J., & Hooven, C. (2018). Interoceptive Awareness Skills for Emotion Regulation: Theory and Approach of Mindful Awareness in Body-Oriented Therapy (MABT). Frontiers in psychology, 9, 798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00798

Robinson, E., Marty, L., Higgs, S., & Jones, A. (2021). Interoception, eating behaviour and body weight. Physiology & behavior, 237, 113434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113434

Sample, C. H., Jones, S., Hargrave, S. L., Jarrard, L. E., & Davidson, T. L. (2016). Western diet and the weakening of the interoceptive stimulus control of appetitive behavior. Behavioural brain research, 312, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.020

Stevenson, R. J., Francis, H. M., Attuquayefio, T., Gupta, D., Yeomans, M. R., Oaten, M. J., & Davidson, T. (2020). Hippocampal-dependent appetitive control is impaired by experimental exposure to a Western-style diet. Royal Society open science, 7(2), 191338. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.191338

Leave a comment