Artificial sweeteners—sugar substitutes that satisfy our cravings for sugar but contain low calories—have become a popular alternative to reduce the risks associated with high-sugar consumption and means of bodyweight management. Yet, the long-term effects of these nonnutritive sweeteners (NNS) have yet to be determined, particularly how our brain responds differently to NNS and nutritive sweeteners (NSW), and consequently, the effects they have on our eating behaviors. While previous clinical trials have investigated the impact of NNS and NSW on neurobehavioral states, these studies were limited as they focused on mostly male cohorts within normal body mass index (BMI).

The long-term effects of these NNS and their effects on eating behaviors have yet to be determined.

To create more generalizable data, Yunker et al. (2021), investigators from the University of Southern California, led a randomized crossover trial that aimed to elucidate the role of gender and BMI status on eating after ingesting NNS compared to NSW.

The authors designed a longitudinal study, in which all participants received a complete sequence of interventions in random order across three separate visits and utilized functional MRI imaging (fMRI) and an ad libitum (Latin for “at one’s pleasure”) buffet meal for evaluation.

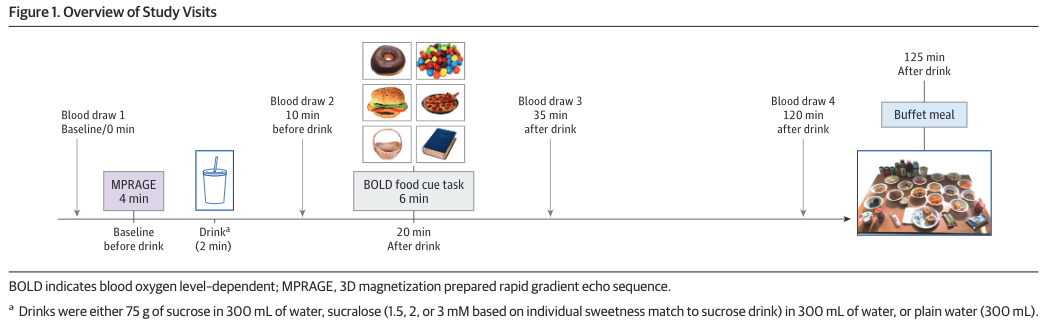

Through fMRI, the authors measured the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals, which reflect neural activity, in various brain areas as participants responded to different types of food cues after ingesting either the sucrose (an NSW), sucralose (an NSS), or water (a control) interventions. At defined intervals, participants also had their blood sampled to assess changes in endocrine response across these interventions (Fig. 1). Caloric intake was measured through the buffet meal for each participant to compare differences in appetitive and feeding behaviors across interventions.

Figure 1. Study design from Yunker et al., JAMA Network Open, 2021.

Artificial Sweeteners May Cause Overeating

BOLD signals were greater in the medial frontal (MFC) and orbitofrontal cortices (OFC) in obese individuals when presented with food cues after ingesting sucralose compared to non-food cues. However, this difference was not observed in participants who’s BMIs were categorized as healthy or overweight, suggesting a distinct intersectional effect of BMI status on one’s neurobehavioral response to food upon ingesting artificial sweeteners. Furthermore, as opposed to male counterparts, BOLD signals were greater in the MFC and OFC of females and were heightened when the participants were females with obesity during the sucralose intervention in the food cue tasks.

The significant increase in BOLD signals within the MFC area/region of the brain is intriguing because previous studies have shown this brain region to be responsible for conditioned motivation for eating in mice (Petrovich, 2007). Likewise, as the region houses higher cognitive function, the higher BOLD signals suggest that participants may have thought more about eating when exposed to food cues after taking artificial sweeteners (Jobson, 2021).

The higher BOLD signals suggest that participants may have thought more about eating when exposed to food cues after taking artificial sweeteners.

The increase in BOLD OFC signal is another interesting result as studies have correlated this brain area with processing the perception of food value, taste reward, and even smell in humans (Small, 2007; Seabrook, 2020). The primary concern concluded by this study is the possibility of overeating—and, in turn, obesity and its comorbidities—when individuals turn to sugar substitutes, especially for women who are already obese.

Although the authors conclude there was minimal effect on endocrine response between NSS and NSW, this study found reduced suppression of ghrelin–the “hunger hormone”–after ingesting sucralose, which suggests that artificial sweeteners may impair the normal homeostatic signaling that regulates feeding behaviors. As such, this would result in a longer period of “feeling hungry” which can contribute to overeating. This is evident in the study in which participants consumed more calories after ingesting sucralose, and this effect was more pronounced in females (no interaction/influence of BMI status found).

Artificial sweeteners may impair the normal homeostatic signaling that regulates feeding behaviors.

Taken together, the findings presented here emphasize the importance of considering biological factors when it comes to assessing the use and efficacy of artificial sweeteners for health-related concerns and body weight management.

References

Jobson, D. D., Hase, Y., Clarkson, A. N., & Kalaria, R. N. (2021). The role of the medial prefrontal cortex in cognition, ageing and dementia. Brain communications, 3(3), fcab125. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab125

Petrovich, G. D., Ross, C. A., Holland, P. C., & Gallagher, M. (2007). Medial prefrontal cortex is necessary for an appetitive contextual conditioned stimulus to promote eating in sated rats. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 27(24), 6436–6441. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5001-06.2007

Small, D. M., Bender, G., Veldhuizen, M. G., Rudenga, K., Nachtigal, D., & Felsted, J. (2007). The role of the human orbitofrontal cortex in taste and flavor processing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1121, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1401.002

Seabrook, L. T., & Borgland, S. L. (2020). The orbitofrontal cortex, food intake and obesity. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN, 45(5), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.190163

Yunker, A. G., Alves, J. M., Luo, S., Angelo, B., DeFendis, A., Pickering, T. A., Monterosso, J. R., & Page, K. A. (2021). Obesity and Sex-Related Associations With Differential Effects of Sucralose vs Sucrose on Appetite and Reward Processing: A Randomized Crossover Trial. JAMA network open, 4(9), e2126313. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26313