- Participants of a qualitative study of individuals with metabolic syndrome published in Health Psychology Open indicated that eating healthfully increases their positive emotions and psychological experiences.

- It also prevents negative emotions, they reported.

- These individuals also believed that positive feelings lead to eating healthfully, creating an upward positive spiral between positive feelings and healthy eating.

In recent years, the number of people with obesity has increased worldwide. This led many authors to speak about an obesity epidemic (e.g., Wong et al., 2022). While people differ in their weight and how much fat their body has, there seems to be a specific point after which the risk of various diseases increases exponentially with further fat accumulation. Represented by body mass index (BMI), the ratio of weight in kilograms, and the square of height in meters, this cutoff point is the BMI value of 30. The World Health Organization declared this BMI the cutoff point for diagnosing obesity (Wilding, 2001). Obesity, paired with several other medical conditions that often co-occur with it, creates what is known as metabolic syndrome.

Obesity, paired with several other medical conditions that often co-occur with it, creates what is known as metabolic syndrome.

What is metabolic syndrome?

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions that includes obesity, elevated blood pressure, and abnormal cholesterol levels—that together increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes (Carrillo et al., 2022). This syndrome currently affects around 35% of U.S. adults (Hirode & Wong, 2020).

Healthy behaviors, such as following a healthy diet or maintaining a healthy weight, are critical for preventing the progression of chronic diseases. However, most people with metabolic syndrome struggle to follow and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Dietary recommendations for people with metabolic syndrome emphasize the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins while avoiding sugar-sweetened beverages and processed and fried foods. In contrast, only 1.7% of people with chronic conditions that could be affected by diet consume high-quality diets, and the share of people without these conditions following such diets is even lower – 1.1% (Chen et al., 2011) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Metabolic Syndrome & Dietary Challenges

What makes people follow healthy diets?

Whether a person will eat a healthy diet depends on many factors. For some people, such diets might not be easily available or beyond what they can afford. For others, following a healthy diet would require a drastic lifestyle change and daily routine. In many cases, cultural factors such as traditional cuisine, eating habits, and even gender norms differ from the requirements of a healthy diet. In the context of socializing and celebrations, people also tend to eat more (Carrillo et al., 2022) and even engage in binge eating, i.e., eating large amounts of food in a short period of time.

In the context of socializing and celebrations, people tend to eat more.

In addition to these wider factors, an individual’s current mood also plays a role. Scientists have identified a type of behavior called emotional eating, which occurs when people eat not because their bodies need nutrients but to cope with negative emotions and stress (Dakanalis et al., 2023; Ljubičić et al., 2023). People tend to prefer highly palatable but unhealthy foods when practicing emotional eating.

Emotional eating occurs when people eat not because their bodies need nutrients but to cope with negative emotions and stress.

The current study

Study author Alba Carrillo and her colleagues wanted to expand scientific knowledge about how positive moods and feelings are associated with a healthy diet in adults with metabolic syndrome (Carrillo et al., 2022). They conducted a qualitative study with the expectation that study participants would share their views about links between a healthy diet and positive psychological experiences and be able to talk about emotion-based motivation for healthy eating.

Study participants were primary care patients from academic medical center outpatient clinics who were willing to be contacted about research studies. They were required to be English-speaking adults with at least three metabolic syndrome risk factors and not meet the U.S. physical activity recommendations of moderate to vigorous activity for at least 150 minutes per week.

Ultimately, searching for participants resulted in 21 individuals completing the study interviews. They were mostly older adults with a mean age of 63 years. 62% were female, and all of them were obese.

The principal investigator of the study conducted semi-structured interviews in which study participants reported on their perceptions of health behaviors and diet, various positive psychological constructs (e.g., feelings of gratitude, optimism, etc.), and healthy eating (e.g., “Does healthy eating lead to an increase in PP constructs?”, “Do PP constructs lead to following a healthier diet?”). All interviews were conducted via phone between June and November 2017.

Eating a healthy diet leads to positive psychological experiences

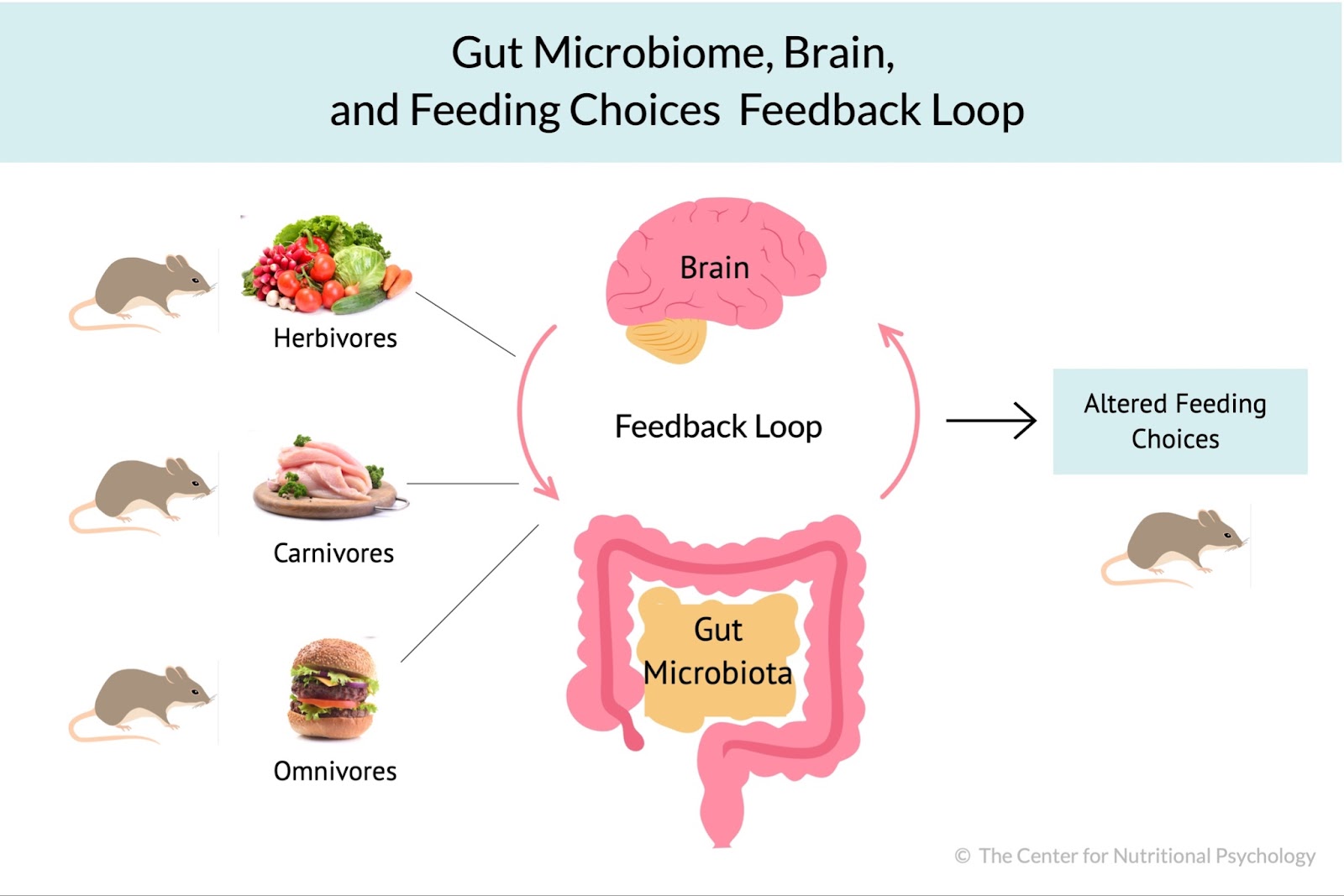

Four main themes emerged from the interviews: (1) eating a healthy diet leads to more positive psychological experiences, (2) positive psychological experiences lead to eating more healthfully, (3) eating a healthy diet prevents negative emotions, (4) healthy behaviors (weight management and exercise) that participants associate with diet can help participants follow a healthy diet (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Main themes of healthy diet and psychological experience

This indicated that participants believed there was an upward healthy spiral of behaviors where following a healthy diet led to more positive psychological experiences and emotions. These positive experiences, in turn, helped participants follow a healthy diet. When discussing healthy eating, participants noted that they experience what study authors referred to as behavioral bundling. Their lifestyle improvements happened together to allow them to continue to eat in a way that can improve their health.

‘Behavioral bundling’ is when participants’ lifestyle improvements happen together to allow them to continue to eat in a way that could improve their health

Exercising improved participants’ mood, leading to a healthier diet

Some participants noted that the relationship between diet and emotions was mediated or co-occurred with exercise. They reported feeling more positive as a consequence of doing exercises. This, in turn, led them to follow a healthier diet.

“I need to eat better to lose weight’. […] I tend to eat better when I do some form of exercise regularly. I even crave different kinds of food. So, I will crave salads more. I’ll look for a piece of fish and not a piece of steak just from doing the exercise,” one participant said.

Conclusion

Overall, participants in this qualitative study clearly stated that positive emotions and psychological experiences motivated them to follow healthy eating patterns, which in turn made them feel more positive.

This indicates that helping people at high risk of developing chronic diseases recognize and cultivate positive emotions may help them improve their adherence to a healthy diet.

The paper “The role of positive psychological constructs in diet and eating behavior among people with metabolic syndrome: A qualitative study” was authored by Alba Carrillo, Emily H Feig, Lauren E Harnedy, Jeff C Huffman, Elyse R Park, Anne N Thorndike, Sonia Kim, and Rachel A Millstein.

References

Carrillo, A., Feig, E. H., Harnedy, L. E., Huffman, J. C., Park, E. R., Thorndike, A. N., Kim, S., & Millstein, R. A. (2022). The role of positive psychological constructs in diet and eating behavior among people with metabolic syndrome: A qualitative study. Health Psychology Open, 9(1), 20551029211055264. https://doi.org/10.1177/20551029211055264

Chen, X., Cheskin, L. J., Shi, L., & Wang, Y. (2011). Americans with Diet-Related Chronic Diseases Report Higher Diet Quality Than Those without These Diseases12. The Journal of Nutrition, 141(8), 1543–1551. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.140038

Dakanalis, A., Mentzelou, M., Papadopoulou, S. K., Papandreou, D., Spanoudaki, M., Vasios, G. K., Pavlidou, E., Mantzorou, M., & Giaginis, C. (2023). The Association of Emotional Eating with Overweight/Obesity, Depression, Anxiety/Stress, and Dietary Patterns: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients, 15(5), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051173

Hirode, G., & Wong, R. J. (2020). Trends in the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA, 323(24), 2526–2528. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4501

Ljubičić, M., Matek Sarić, M., Klarin, I., Rumbak, I., Colić Barić, I., Ranilović, J., Dželalija, B., Sarić, A., Nakić, D., Djekic, I., Korzeniowska, M., Bartkiene, E., Papageorgiou, M., Tarcea, M., Černelič-Bizjak, M., Klava, D., Szűcs, V., Vittadini, E., Bolhuis, D., & Guiné, R. P. F. (2023). Emotions and Food Consumption: Emotional Eating Behavior in a European Population. Foods, 12(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12040872

Wilding, J. P. H. (2001). Causes of obesity. Practical Diabetes International, 18(8), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/PDI.277

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005