Intake of Micronutrients May Quicken Recovery From Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

- An experimental study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders reports that intake of micronutrients might accelerate the improvement of depression and anxiety symptoms

- Symptoms of the group taking micronutrients improved more quickly than those of the placebo group

- The effect of the micronutrients was greater in younger participants, men, those from lower socioeconomic groups, and participants who had previously tried psychiatric medication

Everyone occasionally experiences situations in which they feel low, sad, or not interested in doing anything in particular, having difficulty gathering the motivation to perform daily activities. Similarly, we all feel anxious from time to time, particularly before important events, but the outcome of which is uncertain. However, in some individuals, these feelings become so persistent and frequent that they begin to impair their daily functioning. These are conditions that we refer to as depression (or major depressive disorder) and anxiety disorder.

What are depression and anxiety disorders?

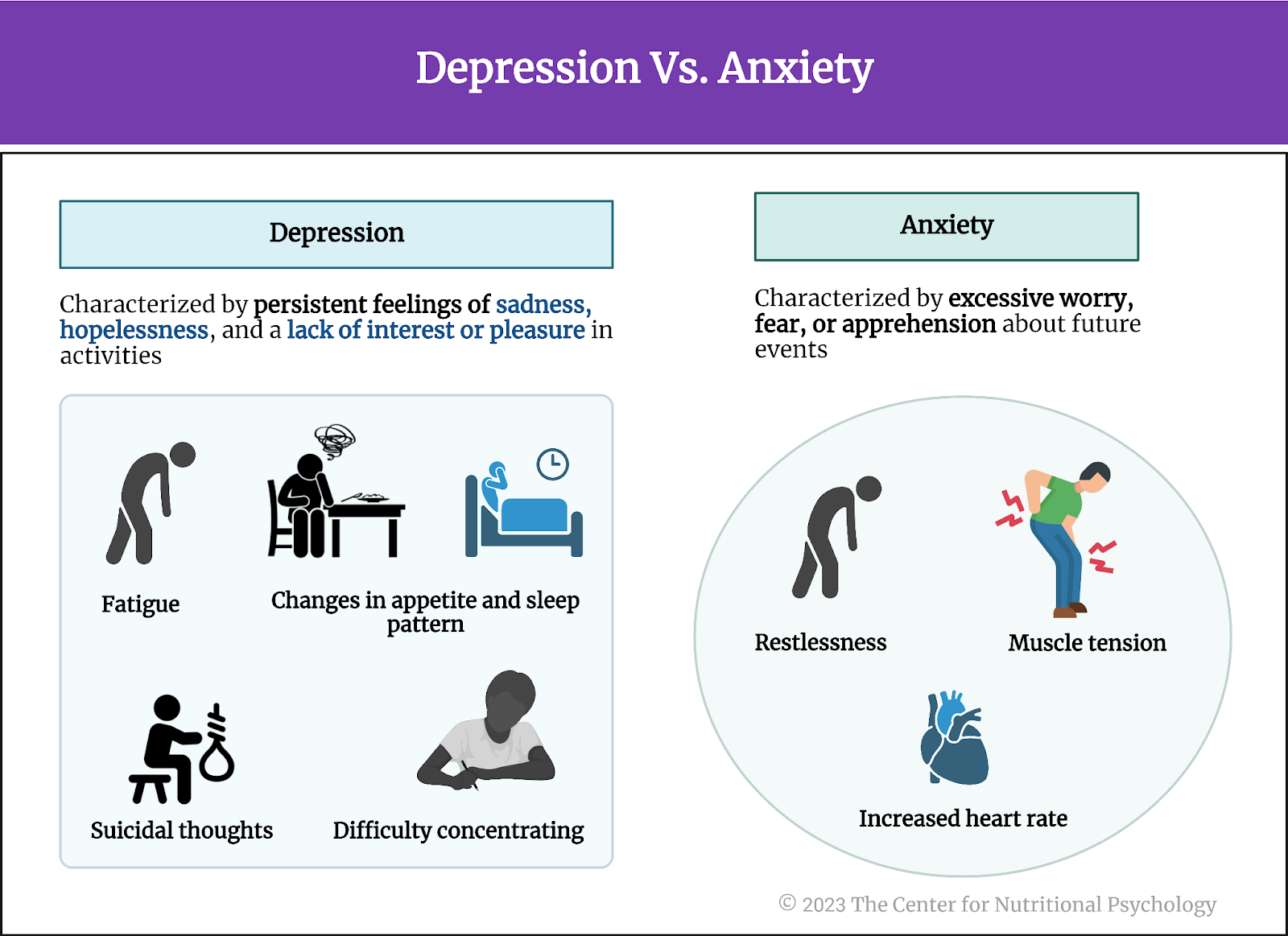

Depression is a mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a lack of interest or pleasure in activities. Symptoms may include changes in appetite and sleep patterns, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and thoughts of death or suicide. It significantly impacts a person’s emotional well-being and daily functioning.

Anxiety, on the other hand, is a condition marked by excessive worry, fear, or apprehension about future events. It can manifest in various forms, such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, or various phobias. Physical symptoms like restlessness, muscle tension, and increased heart rate often accompany anxiety (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Depression Vs. Anxiety

Epidemiological studies indicate that the number of people suffering from anxiety and depression has been increasing across many world countries in recent decades. Analyses indicate that these increases are likely not solely the consequence of better diagnostics and propose that changes to the way we live our lives might have adverse mental health consequences as well (Baxter et al., 2014; Steffen et al., 2020; Weinberger et al., 2018).

The number of people suffering from anxiety and depression has been increasing across many world countries in recent decades

What causes depression and anxiety disorders?

Researchers currently believe that neither depression nor anxiety have a single cause. Available data indicate that they can stem from various factors, including genetics, imbalances in brain chemistry, trauma, and environmental stressors. Recent studies also linked these disorders to certain dietary habits and changes in gut microbiota (Craiovan, 2015; Hedrih, 2023; Leclercq et al., 2020; Samuthpongtorn et al., 2023; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019).

How are these disorders treated?

Currently, psychiatric medications are an accessible treatment option for many people with depression and anxiety disorders (Blampied et al., 2023). Medications are often combined with psychotherapy. However, the effectiveness of these treatments is far from 100%. In many individuals, standard treatment protocols do not result in the withdrawal of symptoms. They sometimes fail to produce even a reduction of symptoms. This has given rise to concepts such as treatment-resistant depression (Fava, 2003). Also, it motivates researchers to seek alternative treatment options (e.g., Zavaliangos-Petropulu et al., 2023) or additions to the existing protocols that could improve their effectiveness.

Among other things, researchers proposed lifestyle changes and physical exercise as potential ways to improve symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, studies of the effectiveness of such treatments indicate mixed results (Kvam et al., 2016; Serrano Ripoll et al., 2015).

Studies conducted in recent decades identified associations between depression and mental health in general with dietary habits and properties of the gut microbiota (Hedrih, 2023a, 2023b; Leclercq et al., 2020; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019). This opened another possible venue for developing potential mental health disorder treatments – dietary intervention.

The current study

Study author Meredith Blampied and her colleagues wanted to explore the potential of dietary intervention in treating anxiety and depression. They note that poverty of diet is a well-established characteristic of people with these two types of disorders. These researchers considered adding micronutrients to patients’ diets as a promising option for a dietary intervention (Blampied et al., 2023).

Some previous studies already established that dietary interventions might effectively improve mental health symptoms. However, to be truly effective, dietary changes introduced through dietary interventions need to be maintained long-term. This is an issue in many patients (Blampied et al., 2023).

Poverty of diet is a well-established characteristic of people with anxiety and depression

What are micronutrients?

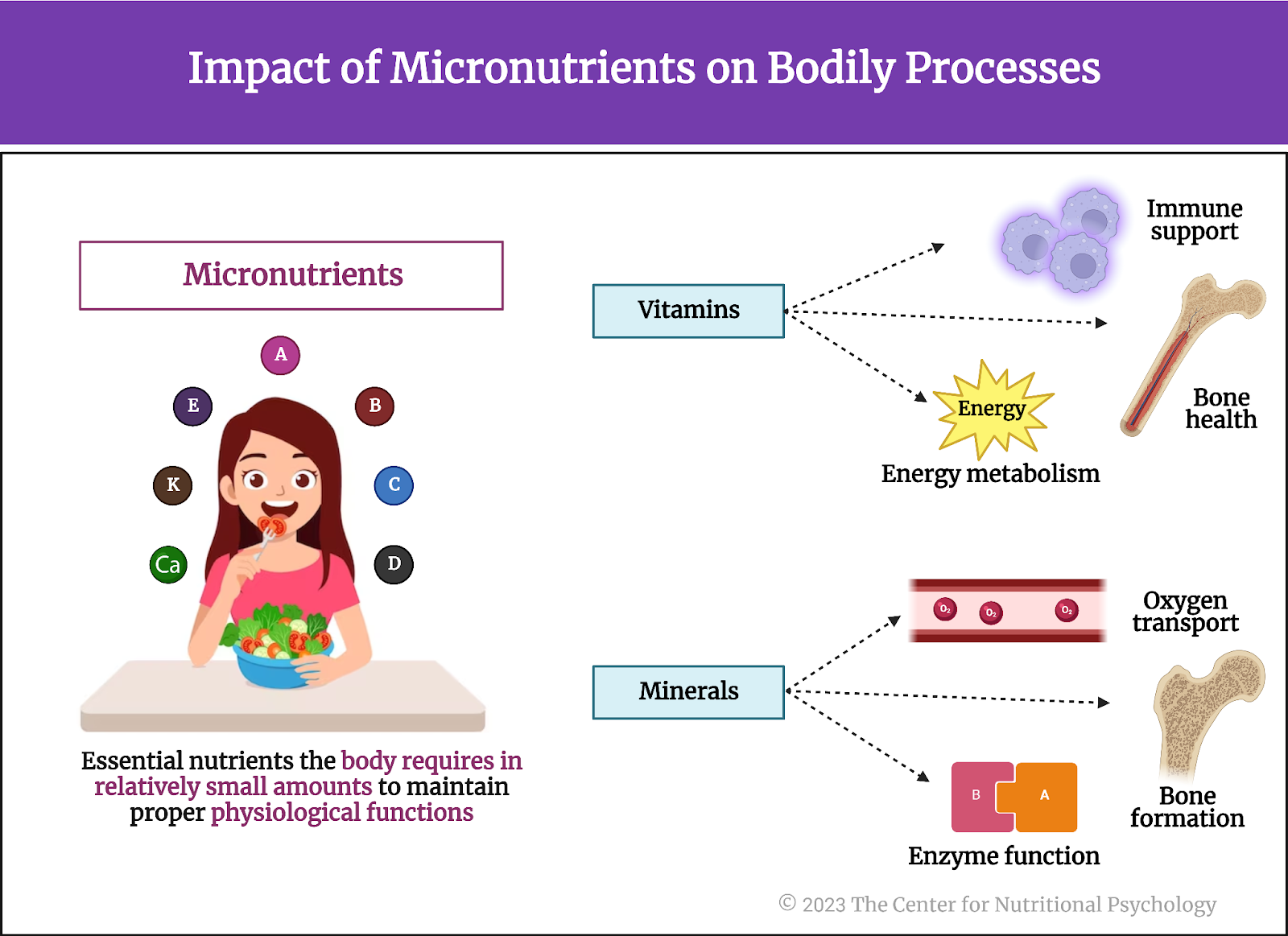

Micronutrients are essential nutrients the body requires in relatively small amounts to maintain proper physiological functions. These include vitamins and minerals, each playing unique roles in supporting various bodily processes. Vitamins such as A, B, C, D, E, and K are organic compounds that contribute to immune support, bone health, and energy metabolism. Minerals, including calcium, iron, zinc, and magnesium, are inorganic elements vital for bone formation, oxygen transport, and enzyme function (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact of micronutrients on Bodily functions

There are several possible mechanisms for how micronutrients might benefit mental health. Some micronutrients are necessary components for the production of neurotransmitters. Other micronutrients help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress or maintain the balance of microbes in the digestive tract. Due to all this, the authors of this study believed that adding a broad spectrum of micronutrients to the diets of individuals suffering from depression or anxiety might lead to a greater reduction of symptoms during treatment (compared to placebo) (Blampied et al., 2023).

There are several possible mechanisms for how micronutrients might benefit mental health

Study participants

Study participants were 150 adults from Canterbury, New Zealand, reporting functionally impairing symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Functionally impairing symptoms are symptoms that adversely affect their relationships, ability to work and/or engage in meaningful activity, and/or that prevent them from engaging in activities of daily living. Researchers recruited these participants between 2018 and 2020 via referrals from general practitioners and through self-referrals.

Study procedure

The study’s authors divided participants randomly into two groups of equal size. Both groups received pills that they were supposed to take over a ten-week study period. The pills and their packaging looked identical. Researchers sent participants the packages with pills for the study period via courier service. There were 12 pills participants had to consume each day, in three doses, four pills per dose.

However, pills delivered to one group (the micronutrient group) contained essential micronutrients, while those delivered to the other group contained maltodextrin (a carbohydrate derived from starch), fiber acacia gum (a natural thickening agent), and very small amounts of cocoa and riboflavin powders (for flavor) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Study Procedure (Blampied et al., 2023)

A full daily dose of micronutrient pills contained vitamins A, C, D, E, B6, B12, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, biotin, pantothenic acid, calcium, iron, phosphorous, iodine, magnesium, zinc, selenium, copper, manganese, chromium, molybdenum, potassium, and several other ingredients.

Of all the individuals involved in the study procedure, only the pharmacist who prepared the pills had access to the group membership list, i.e., knew which participant was in which group. No one else knew this, including the study participants themselves. This was necessary to ensure that participants in both groups remained uncertain whether they were taking micronutrient capsules or a placebo.

Once per week, participants completed online assessments of depression (the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 item scale, PHQ-9), anxiety (the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 question Scale, GAD-7), and a modified questionnaire used to assess side-effects of antidepressants (the Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist, ASEC). Additionally, a clinical psychologist monitored the participants’ condition during the trial. This included assessment phone calls at the start and the end of the study and weekly text message reminders to complete the online assessments.

Symptoms improved faster in the micronutrient group

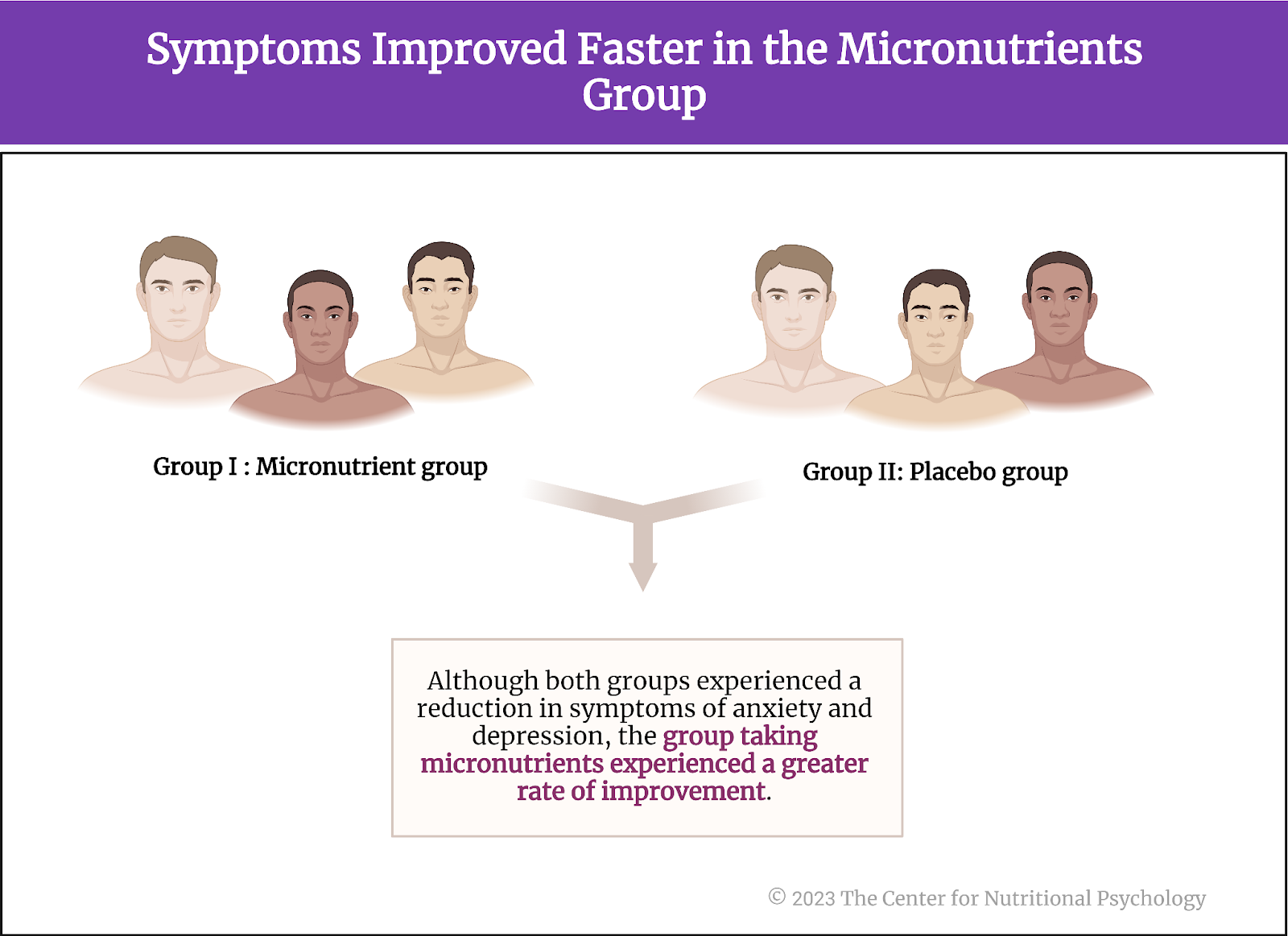

Results showed that anxiety and depression symptom severity decreased in both groups as the study progressed. However, the pace of decrease was faster in the group that consumed micronutrients. This was the case with both symptoms of depression and anxiety (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Symptoms improved faster in the micronutrient group

To verify that these are the effects of micronutrients (and not, e.g., of participants’ expectations), study authors asked participants to report which group they think they are in. Results showed that 62% of participants in the placebo group and 55% from the micronutrient group believed they were in the placebo group. The small difference in percentages indicated to the researchers that their attempt to not let participants know which group they were in was successful. It also increased the likelihood that the observed differences between groups are the effects of micronutrient supplements (and not some other uncontrolled factor).

Results showed that anxiety and depression symptom severity decreased in both groups as the study progressed. However, the decrease pace was faster in the group that consumed micronutrients

Effects of micronutrients depend on age, previous psychiatric treatments, and socioeconomic status

Further analysis revealed that the effects of micronutrients on depressive symptoms depended on age – younger participants in the micronutrient group showed stronger improvements compared to the placebo group as time progressed.

The effects of micronutrients on depressive symptoms depended on age – younger participants in the micronutrient group showed greater improvements compared to the placebo group as time progressed.

Depression symptoms of participants in the placebo group also improved more quickly if they had not previously tried psychiatric medication. This effect was absent for anxiety symptoms. However, the effects of micronutrient intake on the pace of improvement of both depression and anxiety symptoms were greater in participants who previously used psychiatric medication. In a similar manner, depression symptoms of participants with better socioeconomic status in the placebo group improved more quickly. Still, the effects of micronutrients on the improvement of both types of symptoms were greater in participants with lower socioeconomic status.

Men’s symptoms improved slower than women’s, but micronutrients eliminated the difference

Men showed slower improvement in the placebo condition than women. However, in the micronutrient group, there was no difference in the pace of symptom improvement between men and women. This indicates that micronutrient intake accelerated the pace of symptom improvement in men specifically – men’s response to micronutrient intake was stronger.

By the end of the trial, both groups showed similar levels of improvement

Of participants who entered the study with depression symptom severity that indicated depression disorder, 61% from the micronutrient group and 49% from the placebo group achieved clinically significant symptom improvements by the end of the study.

Of participants who started the study with levels of anxiety symptoms indicating anxiety disorder, 62% from the micronutrient group and 56% from the placebo group achieved clinically significant reductions in symptoms.

In a similar fashion, males and females showed similar levels of improvement by the end of the study, and the same was the case with participants who had and those who had not used psychiatric medications earlier. Clinicians’ assessments of levels of improvement in the two groups indicated similar levels of improvement.

Conclusion

Overall, results showed that micronutrient intake might help existing treatments for anxiety and depression by accelerating the pace of recovery. The effects of this dietary intervention seem to be particularly visible in younger individuals, men, those of low socioeconomic status, and individuals with a previous history of psychiatric medication use.

Overall, results showed that micronutrient intake might help existing treatments for anxiety and depression by accelerating the pace of recovery

While it remains unclear why micronutrients showed greater effects in these categories, an important possibility is that they help alleviate dietary deficiencies in some members of these groups, producing greater overall effects in the group as a whole. This indicates that it might be useful for future depression and anxiety treatment programs, but also programs aimed at prevention, to look at the dietary habits of affected individuals along with their psychological status.

The paper “Efficacy and safety of a vitamin-mineral intervention for symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults: A randomized placebo-controlled trial “NoMAD” was authored by Meredith Blampied, Jason M. Tylianakis, Caroline Bell, Claire Gilbert, and Julia J. Rucklidge.

References

Baxter, A. J., Vos, T., Scott, K. M., Ferrari, A. J., & Whiteford, H. A. (2014). The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychological Medicine, 44(11), 2363–2374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713003243

Blampied, M., Tylianakis, J. M., Bell, C., Gilbert, C., & Rucklidge, J. J. (2023). Efficacy and safety of a vitamin-mineral intervention for symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults: A randomised placebo-controlled trial “NoMAD.” Journal of Affective Disorders, 339, 954–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.077

Craiovan, P. M. (2015). Burnout, Depression and Quality of Life among the Romanian Employees Working in Non-governmental Organizations. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187, 234–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.044

Fava, M. (2003). Diagnosis and Definition of Treatment-Resistant Depression. Biol Psychiatry, 53, 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00231-2

Hedrih, V. (2023a). The Diet-Mental Health Relationship in Astronaut Performance. In CNP Articles. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/the-diet-mental-health-relationship-in-astronaut-performance/

Hedrih, V. (2023b). Women Consuming Lots of Artificially Sweetened Beverages Might Have a Higher Risk of Depression, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/women-consuming-lots-of-artificially-sweetened-beverages-might-have-a-higher-risk-of-depression-study-finds/

Kvam, S., Lykkedrang Kleppe, C., Nordhus, I. H., & Hovland, A. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063

Leclercq, S., Le Roy, T., Furgiuele, S., Coste, V., Bindels, L. B., Leyrolle, Q., Neyrinck, A. M., Quoilin, C., Amadieu, C., Petit, G., Dricot, L., Tagliatti, V., Cani, P. D., Verbeke, K., Colet, J. M., Stärkel, P., de Timary, P., & Delzenne, N. M. (2020). Gut Microbiota-Induced Changes in β-Hydroxybutyrate Metabolism Are Linked to Altered Sociability and Depression in Alcohol Use Disorder. Cell Reports, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CELREP.2020.108238

Samuthpongtorn, C., Nguyen, L. H., Okereke, O. I., Wang, D. D., Song, M., Chan, A. T., & Mehta, R. S. (2023). Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Network Open, 6(9), e2334770. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34770

Serrano Ripoll, M. J., Oliván-Blázquez, B., Vicens-Pons, E., Roca, M., Gili, M., Leiva, A., García-Campayo, J., Demarzo, M. P., & García-Toro, M. (2015). Lifestyle change recommendations in major depression: Do they work? Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.059

Steffen, A., Thom, J., Jacobi, F., Holstiege, J., & Bätzing, J. (2020). Trends in prevalence of depression in Germany between 2009 and 2017 based on nationwide ambulatory claims data. Journal of Affective Disorders, 271, 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2020.03.082

Valles-Colomer, M., Falony, G., Darzi, Y., Tigchelaar, E. F., Wang, J., Tito, R. Y., Schiweck, C., Kurilshikov, A., Joossens, M., Wijmenga, C., Claes, S., Van Oudenhove, L., Zhernakova, A., Vieira-Silva, S., & Raes, J. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology, 4(4), 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x

Weinberger, A. H., Gbedemah, M., Martinez, A. M., Nash, D., Galea, S., & Goodwin, R. D. (2018). Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychological Medicine, 48(8), 1308–1315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002781

Zavaliangos-Petropulu, A., McClintock, S. M., Khalil, J., Joshi, S. H., Taraku, B., Al-Sharif, N. B., Espinoza, R. T., & Narr, K. L. (2023). Neurocognitive effects of subanesthetic serial ketamine infusions in treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 333, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.015

Leave a comment