Children Prone to Overeating are More Likely to be Overweight as Adults

Editor’s Note: A longitudinal study conducted in Canada found that individuals who exhibited a propensity for overeating during childhood were at a higher risk of becoming overweight or obese in adulthood. Additionally, individuals categorized as overweight or obese in adulthood demonstrated a higher inclination toward emotional overeating, reduced satiety cues, and a decreased likelihood of being slow eaters. The research also unveiled other connections between childhood eating behaviors, dietary habits, and body mass index (BMI) (Dubois et al., 2022).

Body weight and the body mass index

When we want to track whether our body has accumulated (unwanted) body fat, we usually assess this by weighing ourselves. This is adequate because, after we stop growing, changes in our body mass will most likely be due to changes in our body composition (e.g., accumulating or losing body fat). However, when we need to compare different persons, their differences in height come into play. People with very different weights can have similar body compositions if they are of different height. To solve this issue, scientists use the body mass index.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a statistical indicator calculated by dividing an individual’s weight (in kilograms) by the square of their height (in meters). It serves as a straightforward and widely accepted method of estimating body fat and determining whether an individual falls into categories such as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. BMI provides a convenient way to screen for potential weight-related health issues. However, it has limitations, notably because it does not account for factors like muscle mass, body composition, or fat distribution. An individual with a BMI above 30 is considered obese, while values between 25 and 30 indicate that a person is overweight (Bhatt et al., 2023).

Food intake and obesity

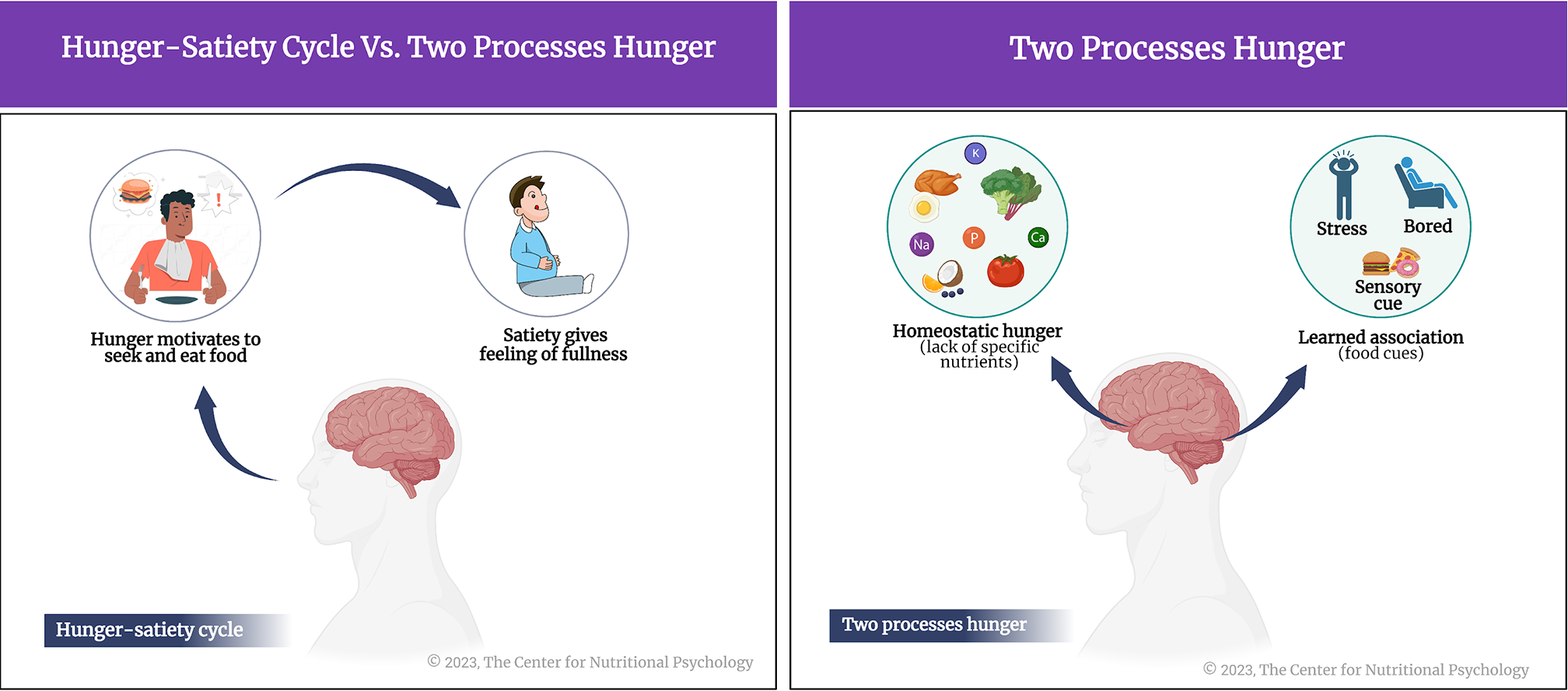

Most obviously, obesity is caused by excessive food intake over a prolonged period. However, the causes of such excessive intake are much more complex. Our body uses a complex mechanism to regulate our food-related behavior. We shift between states of hunger and satiety multiple times every day. While hunger motivates us to seek and eat food, satiety tells us that we should stop eating. Both are linked to our emotions in very complex ways (Swami et al., 2022).

Hunger motivates us to seek and eat food; satiety tells us we should stop eating

However, recent studies indicate that neither hunger nor satiety strictly depend on our body’s nutritional needs. Scientists differentiate between two processes of hunger. One is triggered by a lack of specific nutrients (homeostatic hunger), while the other arises from learned associations between various cues for food (appetite) (Hedrih, 2023) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms to regulate food-related behavior.

Causes of obesity

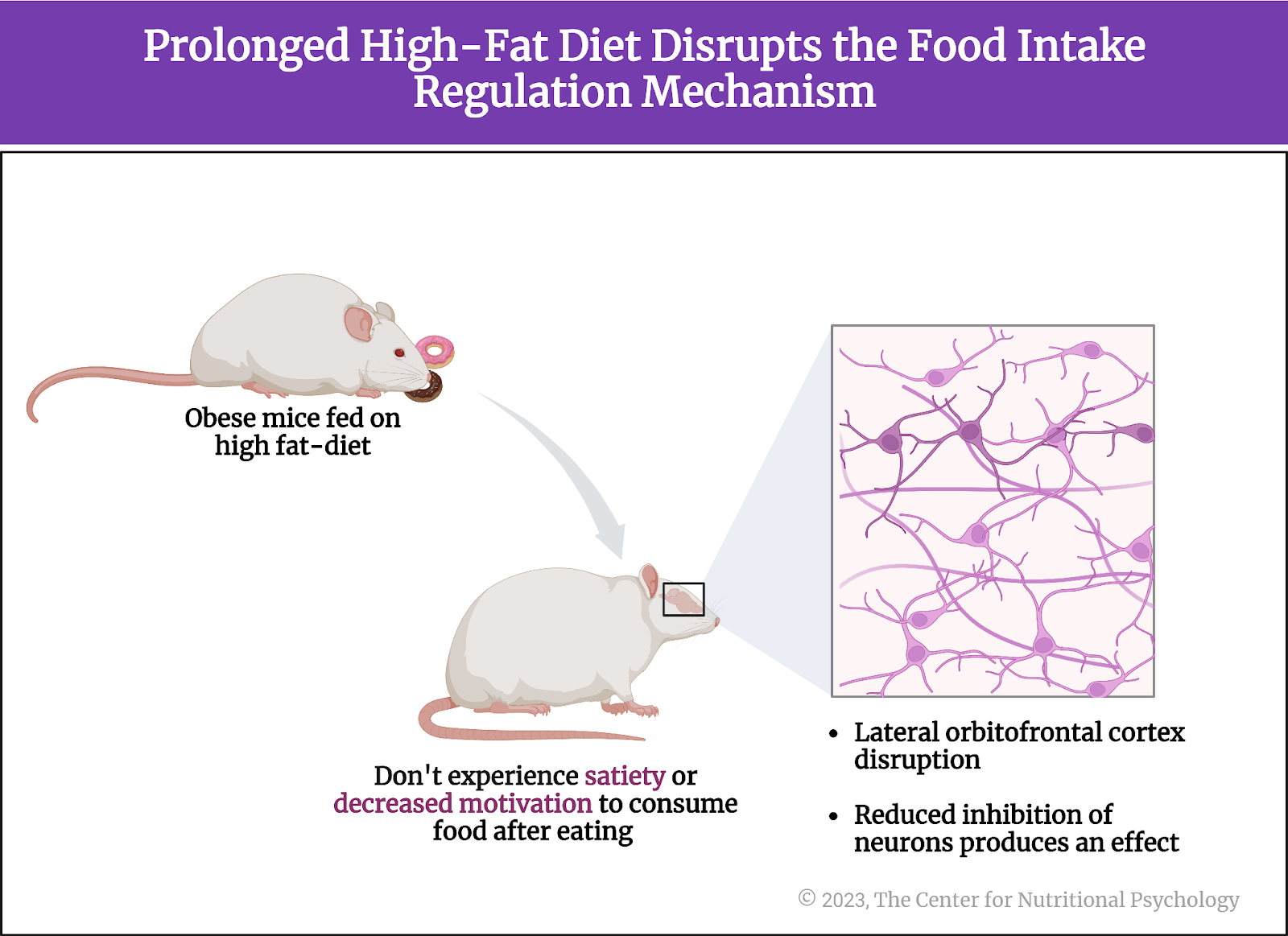

Food intake can often not result in satiety (feeling full or satisfied). Studies showed that mice that became obese because they were fed high-fat diets* do not seem to experience satiety and decreased motivation to consume food after eating.

Food intake can often not result in satiety

Researchers have tracked the cause of this disruption to the lateral orbitofrontal cortex region of the brain. They found that reduced inhibition of neurons produces this effect (Seabrook et al., 2023) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Prolonged high-fat diet disrupts the food intake regulation mechanism

Due to all this, disruption of the hunger-satiety mechanism in the brain is now seen as one of the primary causes of obesity. However, the exact ways this disruption develops in humans are unknown. Scientists have linked the functioning of this mechanism to various genetic and environmental factors, but also to diet (Changizi et al., 2002; Dubois et al., 2022; Stevenson et al., 2023). Of these, diet is the most easily modifiable.

Disruption of the hunger-satiety mechanism in the brain is now seen as one of the primary causes of obesity

The current study

Study author Lise Dubois and her colleagues wanted to explore the links between young adults’ eating behaviors, dietary patterns, and weight status. They also wanted to know whether eating behaviors in childhood are associated with eating habits and weight status in adulthood.

Their study participants were young adults in the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development. The Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development is an ongoing study that has been running since 1998. It started with 2,120 singleton babies who entered the study at 5 months old. Researchers conducting the study periodically collect various data from these individuals, now adults.

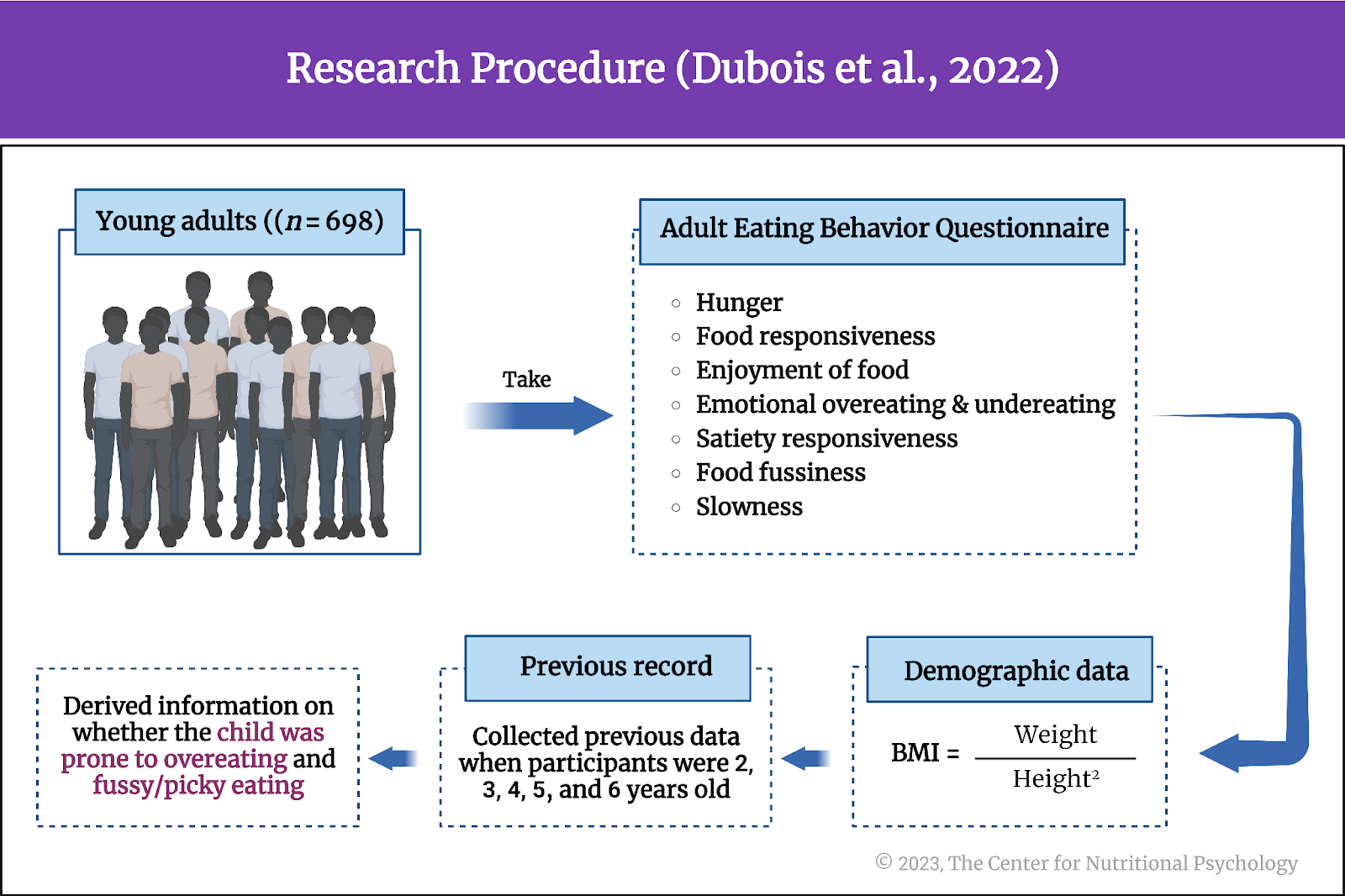

At the time of the last data collection for the current study, these individuals were 22 years of age, and 698 participated.

The study procedure

Participants completed assessments of eating behaviors (the Adult Eating Behavior Questionnaire) and reported how often they ate items from each of the 60 food groups. They also reported their height and weight and several other pieces of demographic data. The study authors used data on height and weight to calculate participants’ body mass index values.

These researchers also used data on participants’ eating behaviors that persons “most knowledgeable” about the participant (who was a child at that time) provided when participants were 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 years old. These persons were most often mothers. From these data, researchers derived information on whether the child was prone to overeating and fussy/picky eating (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Research Procedure

The Eating behavior assessment

The Adult Eating Behavior Questionnaire measures multiple aspects of adult eating behavior. Hunger assesses an individual’s perception of their hunger levels. Questions inquire about how often one feels hungry and how strong that hunger is. Food responsiveness assesses an individual’s sensitivity and responsiveness to the sight and smell of palatable foods and how much these influence eating behaviors. Enjoyment of food evaluates how much an individual enjoys the taste and experience of consuming food.

Emotional overeating and undereating assess the extent to which an individual tends to overeat or undereat as a coping mechanism for emotional distress or negative emotions. Satiety responsiveness examines how often and how strongly an individual experiences the feeling of fullness during and after meals. Food fussiness is the extent to which a respondent is picky about what foods to eat. Slowness in eating assesses the tendency to eat slowly.

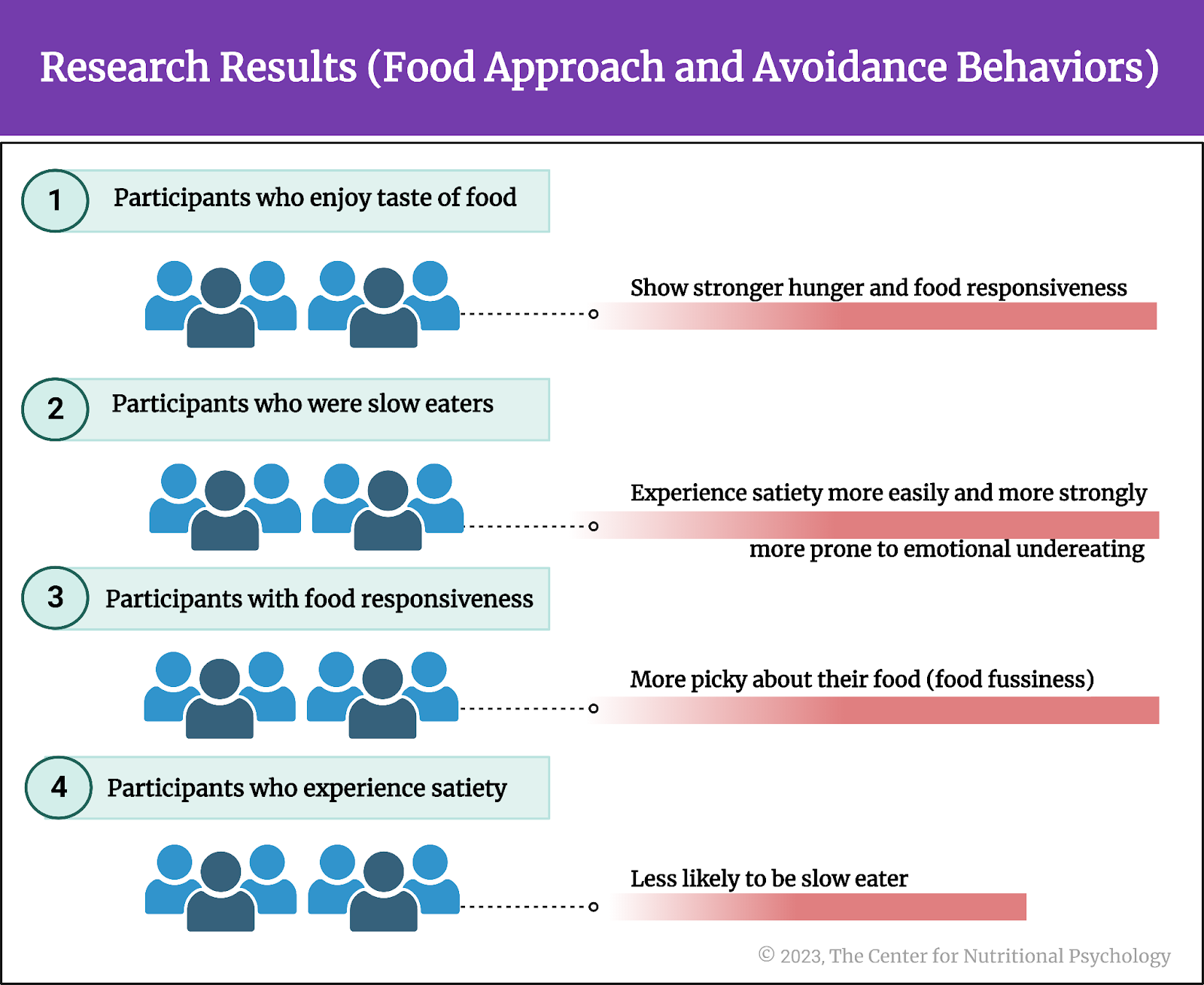

Associations between eating behaviors

Results showed that all food approach behaviors and tendencies to enjoy and eat lots of food were associated. The same was the case with different food avoidance behaviors. Food approach measures were negatively correlated with food avoidance measures. For example, individuals who reported enjoying the taste of food more also reported feeling stronger hunger and being more responsive to the sight and smell of food (food responsiveness).

Individuals who reported enjoying the taste of food more also reported feeling stronger hunger and being more responsive to the sight and smell of food

Participants who were slow eaters tended to experience satiety more easily and more strongly. They were also more prone to emotional undereating. Participants who experienced satiety more easily were more likely to be picky about their food (food fussiness). On the other hand, people who responded more easily to the sight and smell of food were less likely to be slow eaters (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Food approach and avoidance behaviors

Overweight and obese individuals tend to be more positive about food

Results showed that overweight and obese individuals were more prone to emotional overeating and enjoyed the taste of food and the experience of eating more (Enjoyment of food) than their normal-weight peers. On the other hand, they were less prone to emotional undereating, did not experience satiety as easily, and were less likely to be slow eaters.

Males had higher average values on all food behavior measures than females, except food fussiness. In other words, men tended to report experiencing every food behavior, both positive and negative, more strongly than females, except for picky eating. Men and women, on average, reported being picky eaters equally often.

Four food consumption patterns

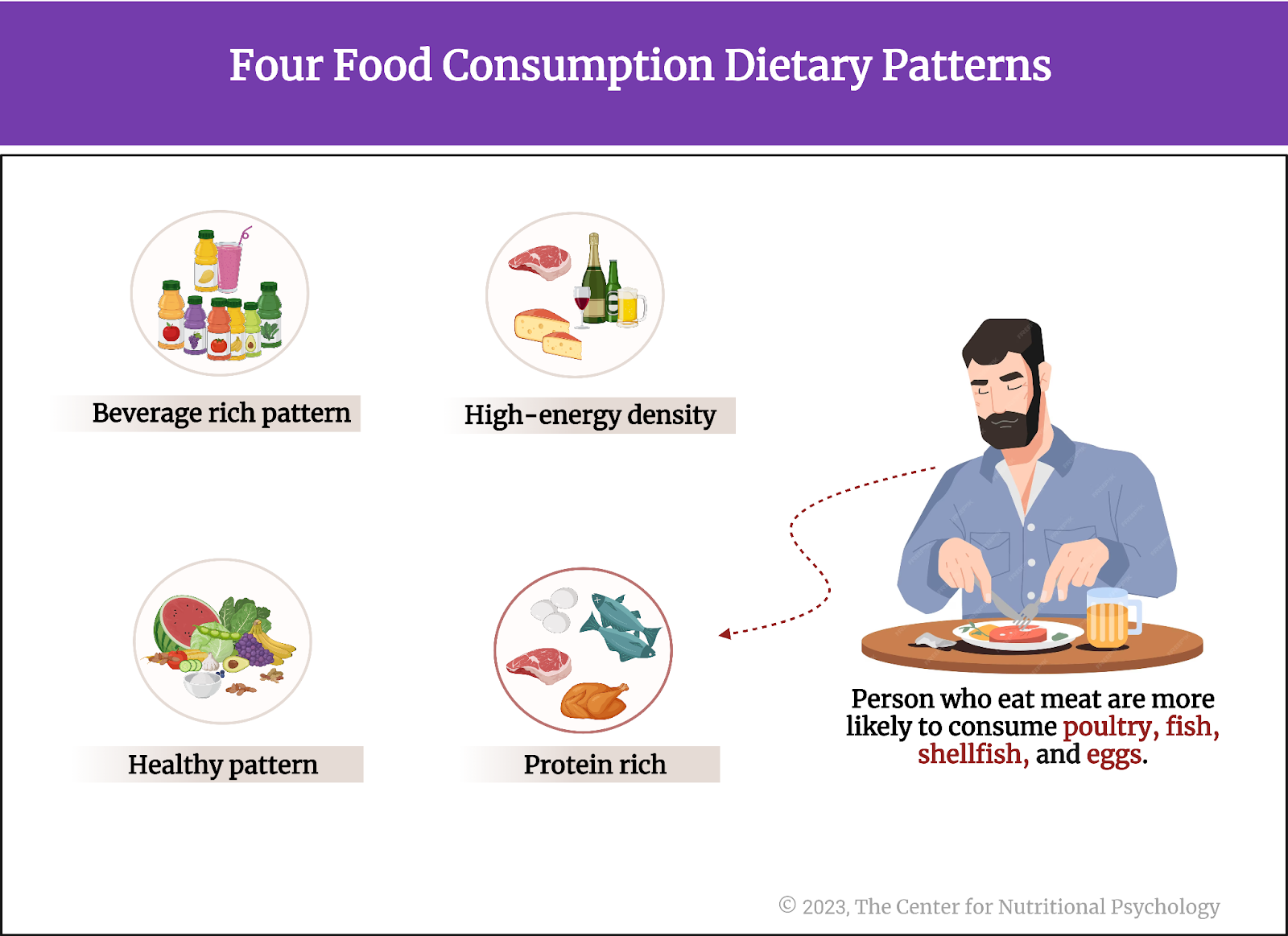

Analysis of data on food item consumption revealed 4 different dietary patterns. Study authors named them healthy (eats legumes, nuts & seeds, whole-grain products, vegetables, and fruit), beverage-rich (a tendency to drink sugar-sweetened beverages and unsweetened milk & plant-based drinks), high energy density (a tendency to eat processed meat, alcohol, cheese and fatty/salty snacks), and protein-rich (a tendency to eat meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, and eggs).

These patterns indicate groups of food items associated in the sense that individuals who consume one food item from the pattern are also more likely to consume other items in that pattern. For example, people who report eating meat are more likely to consume poultry, fish, shellfish, and eggs. Patterns are not different groups of people but tendencies that each individual can have differently (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Four food consumption dietary patterns

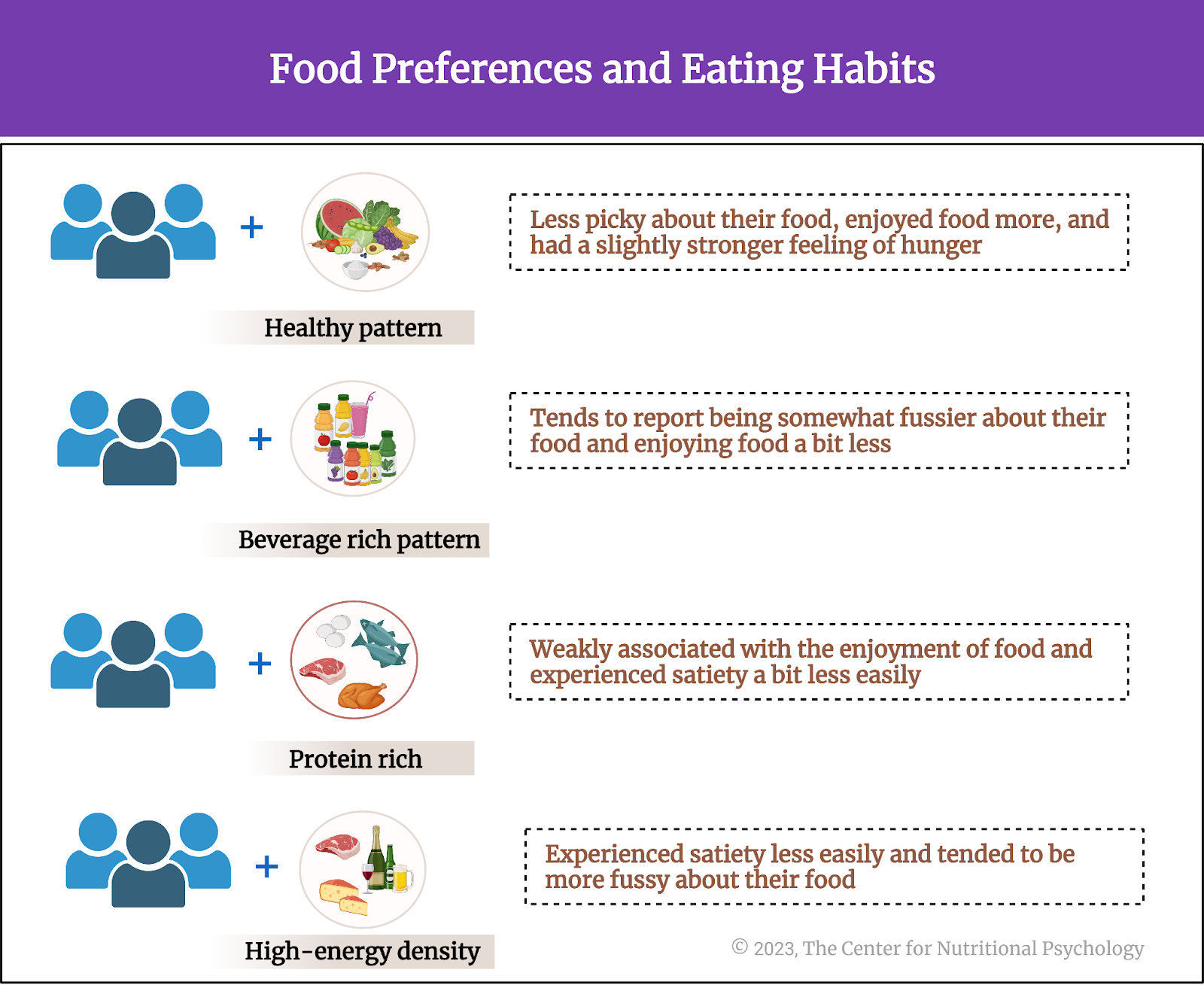

Participants more prone to the healthy dietary pattern tended to be less picky about their food, enjoyed food more, and had a slightly stronger feeling of hunger than those less prone to this pattern. Individuals more often drinking drinks from the beverage-rich pattern tended to report being somewhat fussier about their food and enjoying food a bit less. The protein-rich pattern was very weakly associated with the enjoyment of food. Still, individuals prone to this pattern experienced satiety a bit less easily. Finally, those consuming more foods from the high energy density pattern also experienced satiety less easily. They tended to be more fussy about their food (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Food preferences and eating habits

Individuals who were prone to overeating as children were more likely to be overweight or obese as adults

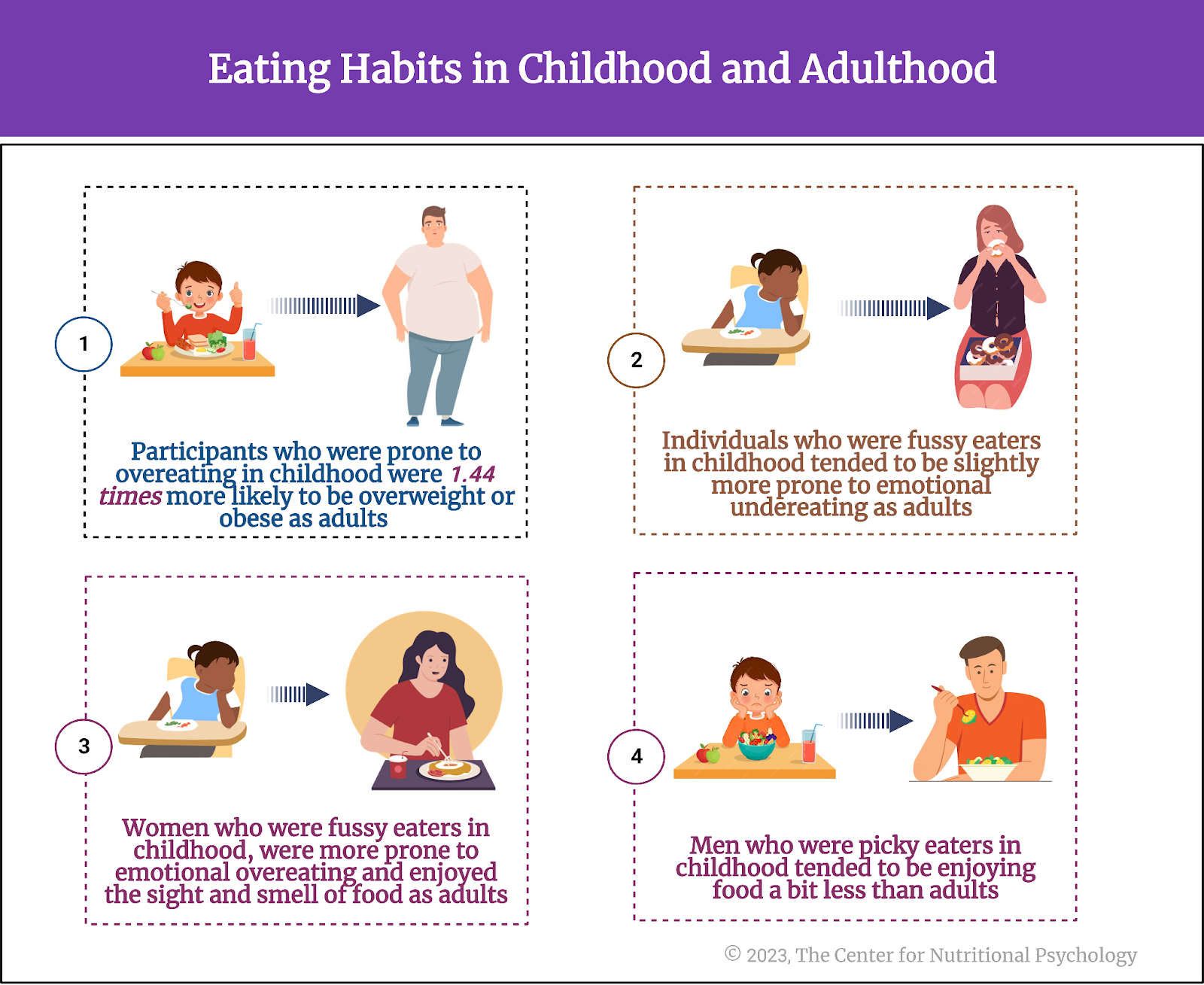

Participants who were prone to overeating in childhood were 1.44 times more likely to be overweight or obese as adults than individuals who were not prone to overeating as children. These individuals also tended to experience satiety less easily than adults compared to those who were not overeating as children.

Individuals who were fussy eaters in childhood tended to be slightly more prone to emotional undereating as adults. They were also more prone to be fussy about their food and were slightly less likely to consume the foods constituting the healthy dietary pattern. There was no association between picky eating in childhood and weight status in adulthood.

Women, but not men, who were fussy eaters in childhood, were more prone to emotional overeating and enjoyed the sight and smell of food as adults. In contrast, men who were picky eaters in childhood tended to be enjoying food a bit less than adults (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Eating habits in childhood and adulthood

Conclusion

Overall, the study reported several associations between eating behaviors and dietary patterns. Individuals more prone to one positive behavior towards food tended to be likelier to show other positive-approaching behaviors (enjoyment of food, responsiveness…). Such individuals were less likely to manifest negative behaviors towards food (be picky or slow eaters, feel satiety easily). Results also showed numerous associations between eating behaviors and dietary patterns, i.e., the food individuals eat.

Most importantly, they showed that individuals prone to overeating in childhood were more likely to be obese or overweight as adults. Additionally, associations, although very weak, were found between eating behaviors in childhood and current eating behaviors over a time gap spanning more than a decade.

These links support the notion that eating behaviors take root in early childhood

These links support the notion that eating behaviors take root in early childhood. Still, the fact that they are generally weak indicates that eating behaviors are very modifiable. Given this, early interventions to establish healthy eating habits in childhood can make it more likely that a person will continue with such habits into adulthood. However, they also indicate that it is never too late to change unhealthy eating behaviors as the repercussions of childhood tendencies on adult eating behaviors appear limited.

The paper “Eating behaviors, dietary patterns and weight status in emerging adulthood and longitudinal associations with eating behaviors in early childhood” was authored by Lise Dubois, Brigitte Bédard, Danick Goulet, Denis Prud’homme, Richard E. Tremblay, and Michel Boivin.

*The study authors do not specify their definition of types of fats in the “high-fat diet” described in this paper (for example, polyunsaturated vs. monounsaturated vs. trans fats).

References

Bhatt, R. R., Todorov, S., Sood, R., Ravichandran, S., Kilpatrick, L. A., Peng, N., Liu, C., Vora, P. P., Jahanshad, N., Gupta, A., & Bhatt, R. R. (2023). Integrated multi-modal brain signatures predict sex-specific obesity status. Brain Communications, 5(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/BRAINCOMMS/FCAD098

Changizi, M. A., McGehee, R. M. F., & Hall, W. G. (2002). Evidence that appetitive responses to dehydration and food deprivation are learned. Physiology and Behavior, 75(3), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00660-6

Dubois, L., Bédard, B., Goulet, D., Prud’homme, D., Tremblay, R. E., & Boivin, M. (2022). Eating behaviors, dietary patterns and weight status in emerging adulthood and longitudinal associations with eating behaviors in early childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-022-01376-z

Hedrih, V. (2023). Are Hunger Cues Learned in Childhood? CNP Articles. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/are-hunger-cues-learned-in-childhood/

Seabrook, L. T., Naef, L., Baimel, C., Judge, A. K., Kenney, T., Ellis, M., Tayyab, T., Armstrong, M., Qiao, M., Floresco, S. B., & Borgland, S. L. (2023). Disinhibition of the orbitofrontal cortex biases decision-making in obesity. Nature Neuroscience, 26(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-022-01210-6

Stevenson, R. J., Bartlett, J., Wright, M., Hughes, A., Hill, B. J., Saluja, S., & Francis, H. M. (2023). The development of interoceptive hunger signals. Developmental Psychobiology, 65(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.22374

Swami, V., Hochstöger, S., Kargl, E., & Stieger, S. (2022). Hangry in the field: An experience sampling study on the impact of hunger on anger, irritability, and affect. PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0269629. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0269629

Leave a comment