- An analysis of UK Biobank data published in Nature Mental Health revealed that elderly individuals eating a balanced diet tended to have better mental health and cognitive abilities than individuals with other types of dietary preferences.

- Study authors identified three additional dietary types – vegetarian, starch-free or reduced starch, and high protein-low fiber.

- The study identified structural differences in specific areas of the brain between individuals eating a balanced diet and those preferring other diet types.

Food preferences are determined by many different factors. In modern societies, individual food choices are primarily defined by food preferences. In other words, people tend to eat the foods they like.

Dietary patterns and health

The link between food and health is very straightforward – if we do not eat, we will eventually die. Our body needs lots of different substances to continue functioning. We need some of them, such as proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, in large quantities. These substances are called macronutrients. Our bodies need many other types of substances in much smaller quantities. These micronutrients include vitamins, minerals, specific essential fatty acids, and many other substances.

In modern societies, individual food choices are primarily defined by food preferences. In other words, people tend to eat the foods they like.

However, a growing body of evidence indicates that specific patterns of consuming foods that our body needs can also lead to adverse health effects (for example, fats, sugars, and proteins are all substances our body needs, but eating too much or focusing on just one can produce adverse effects). Studies indicate that prolonged consumption of a diet rich in foods abundant both in fats and sugars can dysregulate our food intake control system, make us prone to overeating, and eventually lead to overweight and obesity (Hedrih, 2024; Ikemoto et al., 1996; Thanarajah et al., 2023; Wilding, 2001).

Prolonged consumption of a diet rich in foods abundant both in fats and sugars can dysregulate our food intake control system.

Studies also link prolonged consumption of foods rich in refined sugars with the development of type 2 diabetes, mental health conditions like depression and anxiety, and various other health issues (Hedrih, 2023; Huang et al., 2023).

The UK Biobank

Until recently, one of the challenges of studying the links between food intake and disease is that the effects of following specific dietary patterns often materialize after longer periods of time, sometimes years or even decades. Studies of diet-health relationships can be done on rodents in much shorter time periods, but the applicability of such findings to humans remains unknown without actual studies on humans. There are more and more experimental studies of the diet-mental health relationship in humans as well. Still, legal and ethical constraints usually make data collection techniques much less comprehensive.

Another issue with studying the diet-health relationship in humans is that human dietary patterns tend to be very diverse (unless experimentally controlled for research purposes). It is very difficult for a single group of researchers to have a large number of participants in a single research study. The UK Biobank helps solve this issue.

The UK Biobank is a large biomedical database containing in-depth genetic and health information from around half a million UK residents. It was established in 2006 with the aim of improving the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of a wide range of serious and life-threatening illnesses. Data stored in the UK Biobank are available to researchers worldwide.

The current study

Study author Ruohan Zhang and his colleagues wanted to explore the associations between naturally developed dietary patterns and cognitive functions, mental health, blood and metabolic biomarkers, brain characteristics, and genetics (Zhang et al., 2024).

They analyzed data from the UK Biobank from participants who completed a food preference questionnaire. This included 182,990 elderly individuals, the average of whom was 71 years old and 57% female.

The food preference questionnaire consisted of 150 questions that assessed both the sensory qualities of food (e.g., taste) and food preferences. It also asked about health-related behaviors such as physical activity and watching TV. Participants rated how much they liked specific types of foods and beverages.

In addition, the study used data on participants’ mental health, cognitive functioning, blood and metabolic biomarkers, magnetic resonance imaging scans of participants’ brains, and genetic data related to mental disorders (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Procedure (Zhang et al., 2024)

The dietary subtypes

The study authors analyzed the structure of associations between participants’ food preference ratings to identify groups of food items that the same people tend to like or dislike. In other words, they looked for sets of food items such that if a person likes one of the items in a set, it is more likely that he/she will also like the other items and vice versa. They also looked for groups of people with similar food preferences.

In this way, they identified 4 dietary subtypes: 1) Starch-free or reduced starch, 2) vegetarian, 3) high protein and lower fiber, and 4) balanced subtype. Individuals in the first subtype showed a higher preference for fruits, vegetables, and protein foods but a lower preference for foods containing starches (e.g., grains, potatoes, cassava, beans, peas, etc.). The vegetarian subtype showed a higher preference for fruits and vegetables but a lower preference for protein foods. The third subtype had a greater preference for snacks and protein foods but a lower preference for fruits and vegetables. The balanced subtype showed balanced preferences across all food categories (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dietary subtypes

Individuals preferring a balanced diet had better mental health and cognitive function

Results showed that individuals with the balanced dietary subtype had better mental health results than the other 3 categories. They tended to have lower anxiety and depression symptoms, less mental distress and psychotic experiences, less prone to self-harm, reported fewer trauma experiences, and better well-being.

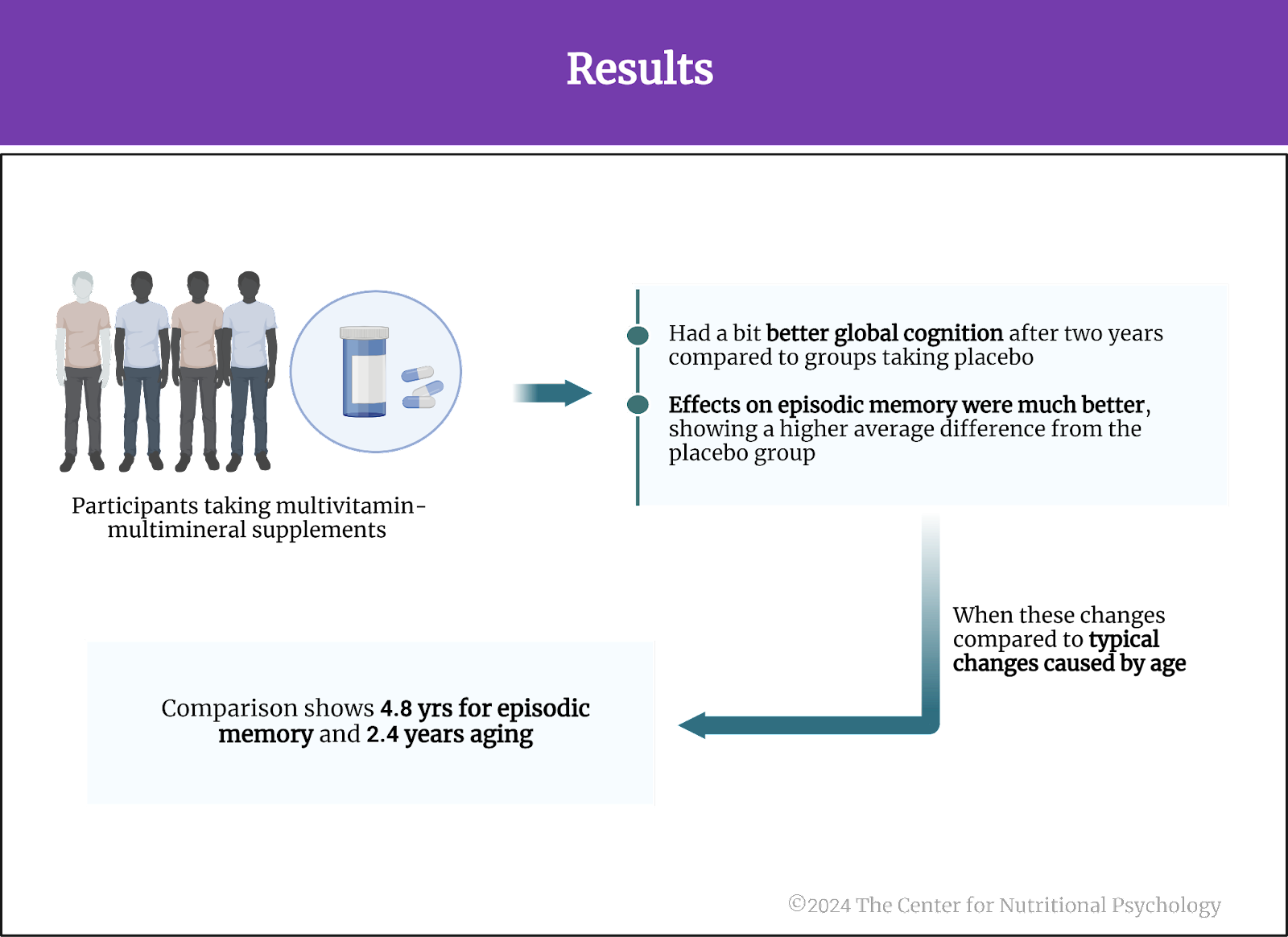

Participants with the balanced diet and those preferring a high protein-low fiber diet had better cognitive functioning compared to the other two groups. Magnetic resonance imaging scans showed certain differences in brain structures between the subtypes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Results (Zhang et al., 2024)

Conclusion

The study shed light on the links between naturally developed dietary patterns and cognitive functioning in elderly individuals. It showed that a diet with balanced preferences for various food categories is associated with better mental health and cognitive abilities than diets focusing on specific types of food while avoiding others.

While the design of this study does not allow any definitive cause-and-effect inferences to be drawn from these results, it stands to reason that a balanced diet, a diet including many different types of food, would best provide all the nutrients needed for the optimal functioning of the human body, allowing for better cognitive functioning even in advanced age.

The paper “Associations of dietary patterns with brain health from behavioral, neuroimaging, biochemical and genetic analyses” was authored by Ruohan Zhang, Bei Zhang, Chun Shen, Barbara J. Sahakian, Zeyu Li, Wei Zhang, Yujie Zhao, Yuzhu Li, Jianfeng Feng, and Wei Cheng.

References

Hedrih, V. (2023, June 6). Health Consequences of High Sugar Consumption. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/health-consequences-of-high-sugar-consumption/

Hedrih, V. (2024, February 19). Consuming Fat and Sugar (At The Same Time) Promotes Overeating, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/16563-2/

Huang, Y., Chen, Z., Chen, B., Li, J., Yuan, X., Li, J., Wang, W., Dai, T., Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wang, P., Guo, J., Dong, Q., Liu, C., Wei, Q., Cao, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 381, e071609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071609

Ikemoto, S., Takahashi, M., Tsunoda, N., Maruyama, K., Itakura, H., & Ezaki, O. (1996). High-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and obesity in mice: Differential effects of dietary oils. Metabolism, 45(12), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90185-7

Thanarajah, S. E., Difeliceantonio, A. G., Albus, K., Br, J. C., Tittgemeyer, M., Small, D. M., Thanarajah, S. E., Difeliceantonio, A. G., Albus, K., Kuzmanovic, B., & Rigoux, L. (2023). Habitual daily intake of a sweet and fatty snack modulates reward processing in humans. Cell Metabolism, 35, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.015

Wilding, J. P. H. (2001). Causes of obesity. Practical Diabetes International, 18(8), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/PDI.277

Zhang, R., Zhang, B., Shen, C., Sahakian, B. J., Li, Z., Zhang, W., Zhao, Y., Li, Y., Feng, J., & Cheng, W. (2024). Associations of dietary patterns with brain health from behavioral, neuroimaging, biochemical and genetic analyses. Nature Mental Health, 2(5), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00226-0