- A study of women published in JAMA Network Open found that women with higher perceived social isolation tend to have altered neural activity in response to pictures of food

- This altered activity was detected in brain regions responsible for appetite and food-related motivation and included the default mode, executive control, and visual attention networks

- More socially isolated women also tended to be more overweight and obese, to have lower diet quality, more maladaptive eating behaviors, and poorer mental health

Sometimes, eating something will make us feel better when we are sad or experience strong negative emotions. Some foods are so tasty that eating them feels like a rewarding experience. People associate some foods with positive memories, so eating them will improve their emotional state by invoking them. But what happens when negative emotions are persistent? For example, when we generally feel lonely?

Social isolation

Perceived social isolation, also known as loneliness, is one’s subjective appraisal of his/her available social relationships and community support (Zhang et al., 2024). Loneliness is entirely subjective and does not necessarily rely on how many social connections one objectively has. A person can feel lonely while being surrounded by people.

Loneliness is entirely subjective and does not necessarily rely on how many social connections one objectively has.

Loneliness is not a pleasant feeling. Feeling lonely adversely impacts our well-being. However, studies indicate that loneliness might have a broader adverse impact on our health. Lonely individuals seem to be at an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, cognitive decline, and unhealthy eating behaviors (Zhang et al., 2024), but also dying of cancer (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2003; Park et al., 2020). Some authors suggest that health risks created by loneliness are on par with those created by chronic high blood pressure, obesity, or smoking (Singer, 2018).

However, it should be noted that these observations are just associations. While loneliness may lead to these adverse health effects, health problems can make socialization difficult or impossible, creating an association with loneliness.

Social isolation and eating behaviors

Loneliness may increase the risk of obesity. It may also worsen eating behaviors and eating disorders (Zhang et al., 2024). Previous studies established that negative emotions make individuals more likely to overeat (Zeeck et al., 2011). When intense emotions overwhelm an individual’s capacity to self-regulate their own emotional well-being, binge eating behaviors may emerge as a coping mechanism.

Loneliness may increase the risk of obesity. It may also worsen eating behaviors and eating disorders.

There is both scientific and anecdotal evidence of the phenomenon of being “hangry,” i.e., becoming angry while hungry (Hedrih, 2023; Swami et al., 2022). A similar link may exist between loneliness and hunger as well.

The current study

Study author Xiaobei Zhang and his colleagues note that there is emerging evidence that the brains of individuals experiencing chronic loneliness undergo functional changes that may contribute to obesity, altered eating behaviors, and associated psychological symptoms. They wanted to explore the links between loneliness and the brain’s responses to the sight of food better.

These authors hypothesized that several brain networks will show increased activation in lonely individuals when viewing foods. The size of this increase would likely be higher in obese individuals who already have altered eating behaviors and worsened mental health. These authors also hypothesized that reactions would be particularly strong to sweet foods, given their highly rewarding nature.

The study participants were 93 women of reproductive age from Los Angeles, California. Their average age was 25, and they ranged between 18 and 50. The study authors recruited them through advertisements.

The study authors took participants’ weight and height measurements (to calculate body mass index) and estimated their body composition. Participants provided data on their diet style and quality (the UCLA Diet Checklist and the Healthy Eating Index), age, marital status, and socioeconomic status. They completed an assessment of perceived social isolation (the Perceived Isolation Scale). Based on this assessment, the study authors divided participants into two groups – the high-isolation group and the low-isolation group.

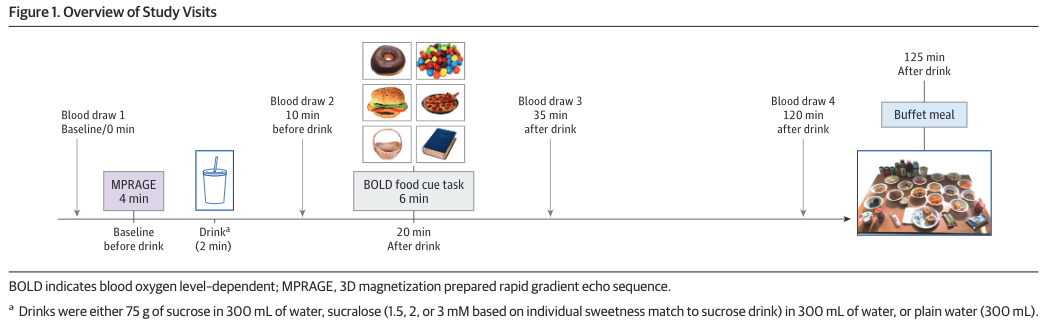

Aside from this, participants completed assessments of food craving (the General Food Craving Questionnaire), eating behaviors (the Reward-based Eating Drive, the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire), food addiction (the Yale Food Addiction Scale), resilience (the Connor-Davidson Resilience scale), anxiety and depression symptoms (the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), and affect (the Positive Affect – Negative Affect Schedule). Participants also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging while viewing a slideshow with pictures of different types of food – unhealthy savory, unhealthy sweet, healthy savory, healthy sweet, and non-food images (i.e., pixelated images created from food pictures to serve as controls) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Procedure (Zhang et al., 2024)

Lonely individuals had higher fat mass percentage, ate lower quality diets, and had worse mental health

Results showed that the high loneliness group of participants tended to have higher fat mass percentage and ate diets of lower quality. They showed more maladaptive eating behaviors (cravings, reward-based eating, uncontrolled eating, and food addiction scores) and more anxiety and depression symptoms. They also tended to have lower psychological resilience.

The high loneliness group of participants tended to have a higher fat mass percentage and eat lower-quality diets.

Lonely individuals tended to have altered brain reactivity to food pictures

Participants in the high social isolation group also tended to have altered brain reactivity to the pictures of food in regions of the brain belonging to the default mode, executive control, and visual attention networks compared to the low social isolation group (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study results (Zhang et al., 2024)

The default mode network is a brain network active during rest and involved in self-referential thoughts, mind-wandering, and daydreaming. The executive control network is responsible for high-level cognitive functions such as decision-making, problem-solving, and maintaining attention to tasks. The visual attention network directs attention to visual stimuli, enabling the processing and prioritization of visual information in the environment.

Neural responses to sweet foods were associated with altered eating behaviors and psychological symptoms. Statistical analysis showed that these altered brain responses may mediate the relationship between loneliness and maladaptive eating behaviors, increased body fat composition, and diminished positive emotions.

The study confirmed the link between social isolation and obesity.

Conclusions

The study confirmed the link between social isolation and obesity. It identified altered brain responses to the sight of food in women who reported higher feelings of loneliness. These findings underscore the need for overweight and obesity treatments to take into account the whole psychological and social situation of an individual rather than focusing on eating behaviors alone.

The paper “Social Isolation, Brain Food Cue Processing, Eating Behaviors, and Mental Health Symptoms” was authored by Xiaobei Zhang, Soumya Ravichandran, Gilbert C. Gee, Tien S. Dong, Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez, May C. Wang, Lisa A. Kilpatrick, Jennifer S. Labus, Allison Vaughan, and Arpana Gupta.

References

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 17(1, Supplement), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9

Hedrih, V. (2023). Food and Mood: Is the Concept of ‘Hangry’ Real? CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/food-and-mood-is-the-concept-of-hangry-real/

Park, C., Majeed, A., Gill, H., Tamura, J., Ho, R. C., Mansur, R. B., Nasri, F., Lee, Y., Rosenblat, J. D., Wong, E., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). The Effect of Loneliness on Distinct Health Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514

Singer, C. (2018). Health Effects of Social Isolation and Loneliness. Journal of Aging and Care, 28(1), 4–8.

Swami, V., Hochstöger, S., Kargl, E., & Stieger, S. (2022). Hangry in the field: An experience sampling study on the impact of hunger on anger, irritability, and affect. PLOS ONE, 17(7), e0269629. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0269629

Zeeck, A., Stelzer, N., Linster, H. W., Joos, A., & Hartmann, A. (2011). Emotion and eating in binge eating disorder and obesity. European Eating Disorders Review, 19(5), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1066

Zhang, X., Ravichandran, S., Gee, G. C., Dong, T. S., Beltrán-Sánchez, H., Wang, M. C., Kilpatrick, L. A., Labus, J. S., Vaughan, A., & Gupta, A. (2024). Social Isolation, Brain Food Cue Processing, Eating Behaviors, and Mental Health Symptoms. JAMA Network Open, 7(4), e244855. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.4855