Women Consuming Lots of Artificially Sweetened Beverages Might Have a Higher Risk of Depression, Study Finds

Editor’s Note: A longitudinal study of a large group of women between 2003 and 2017 found that a high ultra-processed food intake was associated with several adverse health outcomes. These included greater body mass index, higher smoking rates, higher likelihood of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Individuals often eating ultra-processed foods were less likely to exercise regularly and had an increased risk of depression. The increased risk of depression was mainly associated with frequent consumption of artificially sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners (Samuthpongtorn et al., 2023). The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

What is food processing?

Almost all foods are processed to some extent (Monteiro et al., 2019). Humans process food to preserve it so that it would not spoil, to make it edible, to destroy harmful microorganisms or chemical compounds, to improve its taste, and for many other reasons.

Many foods are not edible unless processed. For example, cassava, a root vegetable that is one of the staple foods in many parts of the world, contains large amounts of cyanogenic glycosides. If consumed raw, these compounds can release the poison cyanide. Thorough processing, which involves peeling, soaking, and cooking, is necessary to make cassava safe to eat. This thorough processing turns a poisonous plant into an important source of nutrients for humans.

Many foods are not edible unless processed

Other types of food would readily spoil without processing. For example, left on their own, meat, fish, and many fruits and vegetables would spoil very quickly in most environments. However, drying, curing, and canning allow us to preserve these foods for long periods, ensuring food is available throughout the year. Food processing such as this is crucial for creating a stable and dependable human food supply. Due to all this, it is not helpful to be critical of food processing in general. Food processing is necessary.

It is worth noting, however, that the way humans process foods – even the same food – can vary significantly depending on various factors, for example, the setting. Processing food at home (e.g., cooking a meal) differs from processing food on an industrial level (e.g., preparing the same meal industrially for mass distribution). The latter involves specific manufacturing techniques and often uses additives (e.g., colorants, flavor enhancers, preservatives, pesticides, etc.) even in relatively unprocessed foods.

With regard to food processing, researchers have developed classifications of various food items

The NOVA food classification system

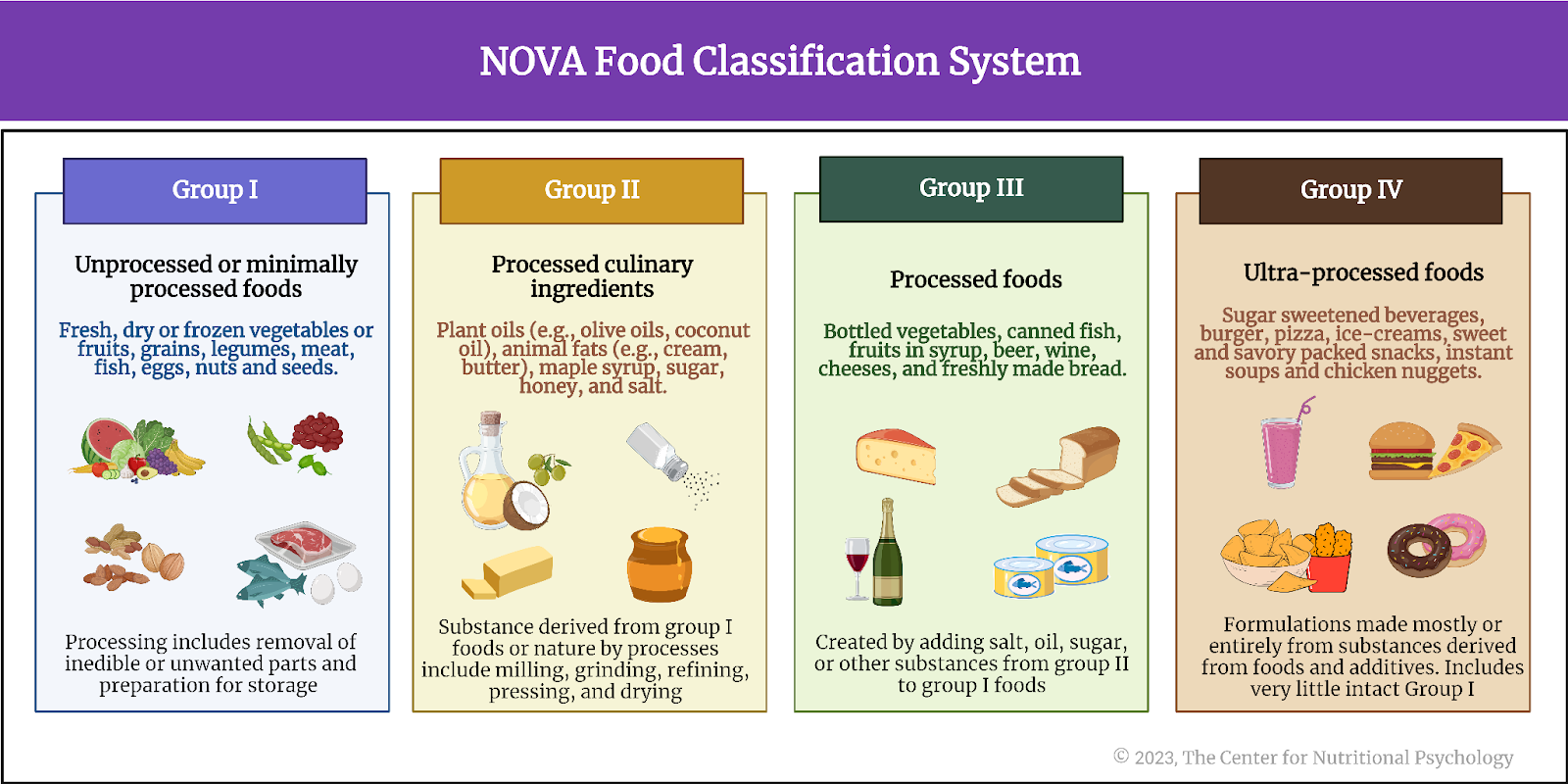

With regard to processing, researchers have developed various classifications of food items. One very popular classification is the NOVA classification system (Monteiro et al., 2018), which groups foods into four categories according to the extent and purpose of processing they undergo.

The NOVA system categories are (see Figure 1):

- Group 1. Unprocessed or minimally processed foods – natural foods altered only by processes that include removing inedible or unwanted parts and preparation for storage (e.g., vacuum-packaging, drying, pasteurization, refrigeration, freezing, roasting…)

- Group 2. Processed culinary ingredients – derived from group 1 foods and processed to make durable products suitable for kitchens to prepare, season, and cook group 1 foods. These processes include milling, grinding, refining, pressing, and drying. Examples are oils, butter, sugar, and salt.

- Group 3. Processed foods – created by adding salt, oil, sugar, or other substances from group 2 to group 1 foods. Examples include bottled vegetables, canned fish, fruits in syrup, cheeses, and freshly made bread.

- Group 4. Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives with little if any, intact group 1 food (Monteiro et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Nova food classification system and examples of foods in each class

Why are ultra-processed foods special?

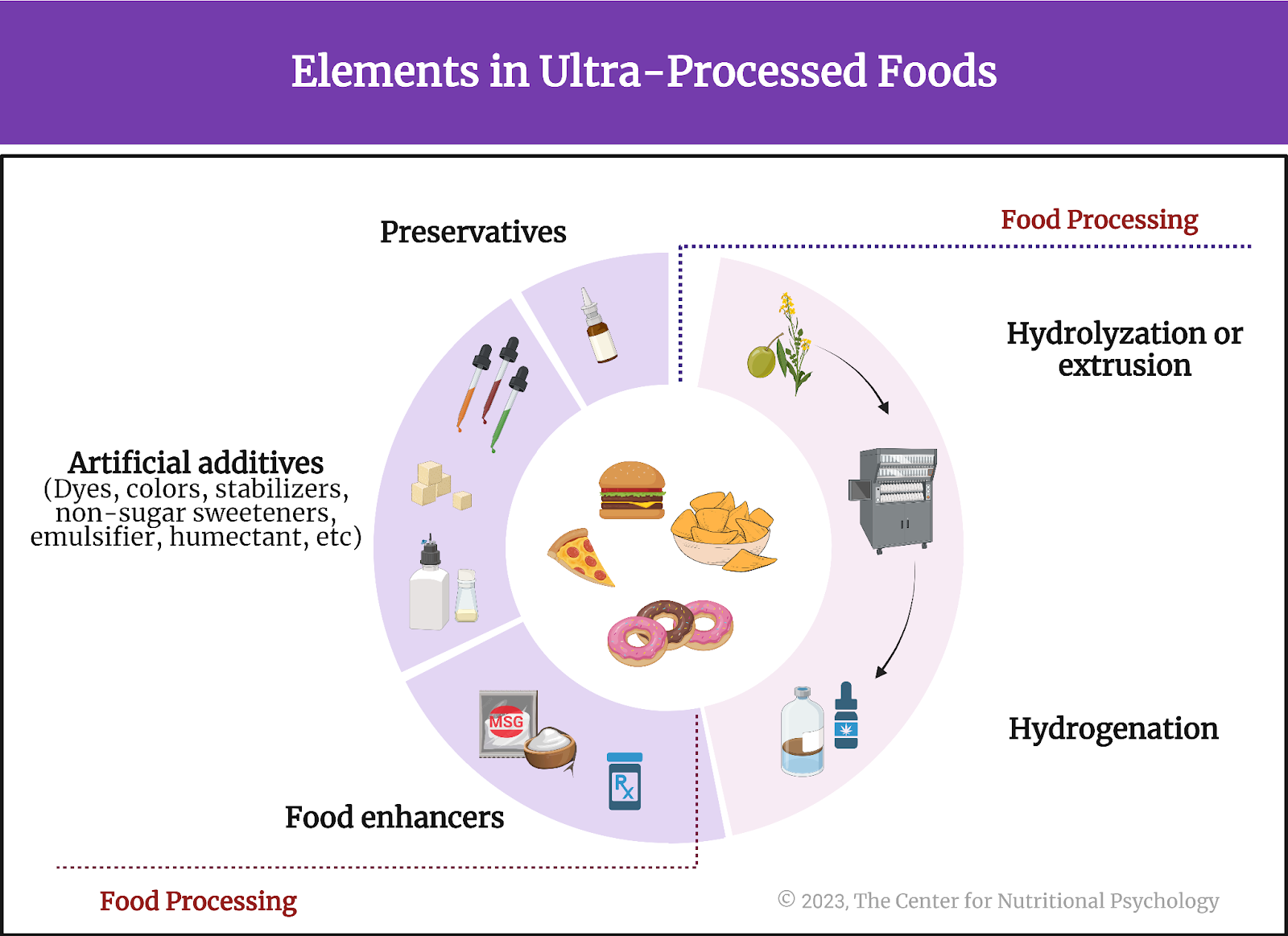

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are heavily processed before consumption. They typically contain numerous artificial additives, preservatives, and flavor enhancers. These additives include dyes, color stabilizers, non-sugar sweeteners, de-foaming, anti-caking or glazing agents, emulsifiers, humectants, and many others. Some processes used in preparing these foods, such as hydrogenation, hydrolyzation, or extrusion, are exclusively industrial processes that cannot be performed in a regular kitchen (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Elements in ultra-processed foods

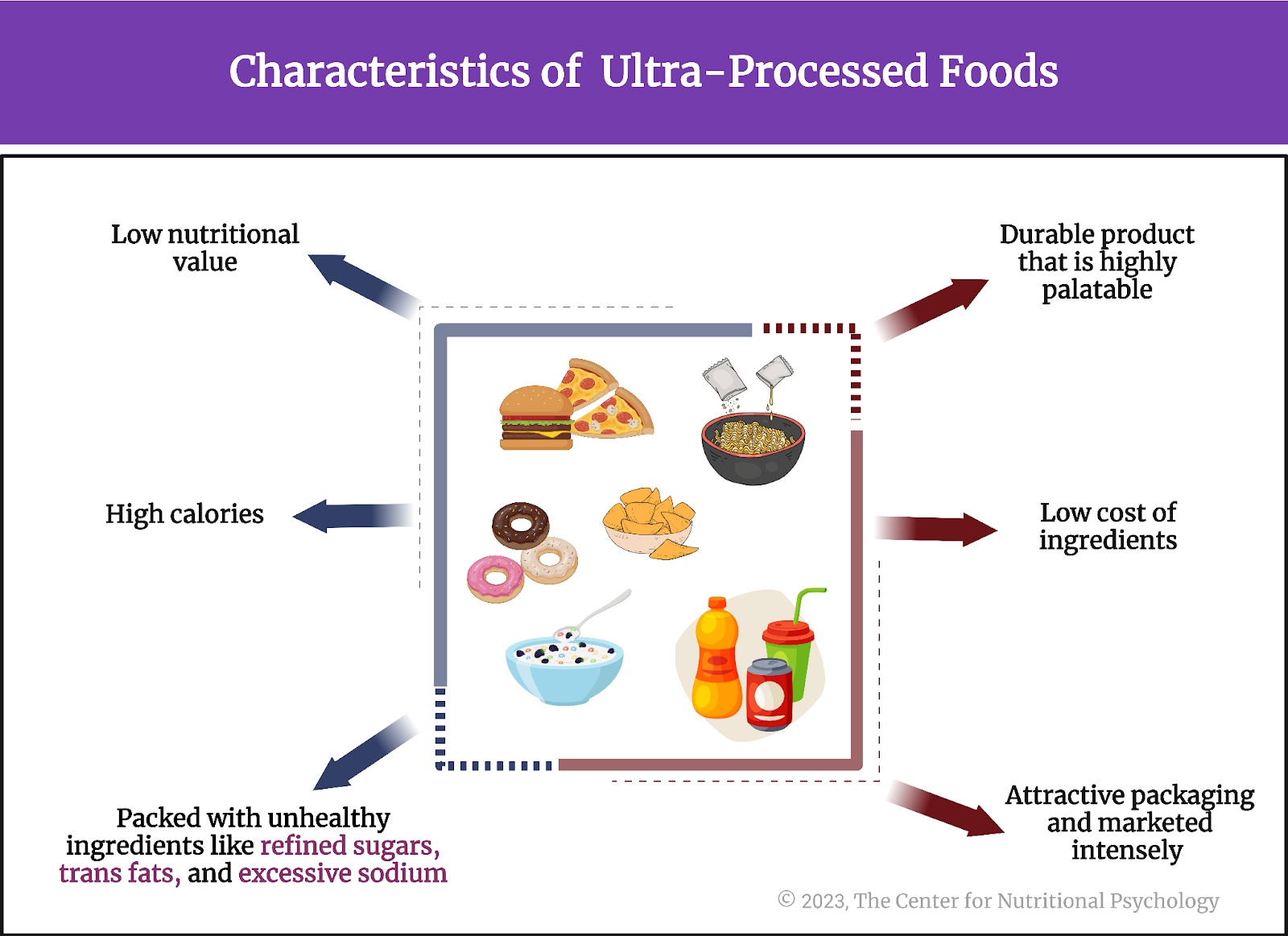

Ultra-processed foods are often low in nutritional value, high in calories, and packed with unhealthy ingredients like refined sugars, trans fats, and excessive sodium. Examples of ultra-processed foods include instant noodles, artificial sweeteners, artificially sweetened beverages, sugary cereals, microwaveable meals, reconstituted meat products, sweet and savory packaged snacks, pre-prepared frozen dishes, and soft drinks. The overall purpose of ultra-processing is to create a durable product that is highly palatable but also highly profitable due to the low cost of ingredients. Ultra-processed foods usually have attractive packaging and are marketed intensely (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Characteristics of ultra-processed foods

Ultra-processed foods and health risks

One of the concerning aspects of ultra-processed foods is their link to various health problems. Studies have linked the regular consumption of these foods with a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and certain types of cancer. Ultra-processed foods often lack essential nutrients like fiber, vitamins, and minerals important for overall health.

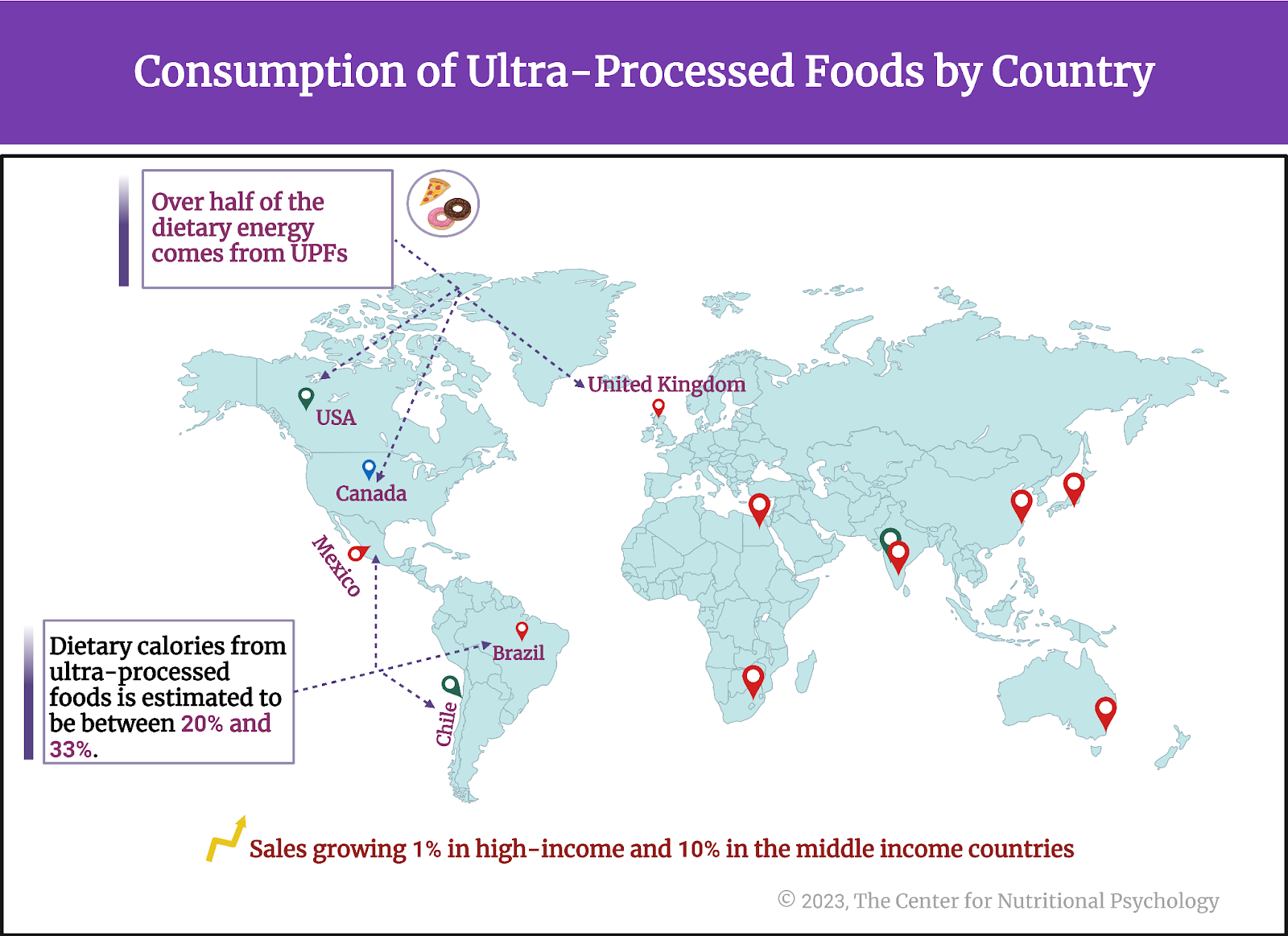

Despite these health risks, over half of the dietary energy consumed by individuals from high-income countries such as the USA, Canada, or the UK comes from ultra-processed foods. In middle-income countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, the share of dietary calories from ultra-processed foods is estimated to be between 20% and 33%. Additionally, the sales of these foods are growing by about 1% per year in high-income countries and up to 10% per year in middle-income countries (Monteiro et al., 2019) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Consumption of UPFs by Country.

Over half of the dietary energy consumed by individuals from high-income countries such as the USA, Canada, or the UK comes from ultra-processed foods

The current study

Study author Chatpol Samuthpongtorn and his colleagues wanted to examine whether consuming ultra-processed foods might be associated with the risk of depression. They were aware of findings linking the consumption of ultra-processed foods with many different diseases. Still, they noted that many studies that reported these findings relied only on short-term dietary data and could not account for various factors that could have influenced the results. They also wanted to know if any specific ultra-processed foods are linked to depression and whether the timing of ultra-processed food consumption might play a role.

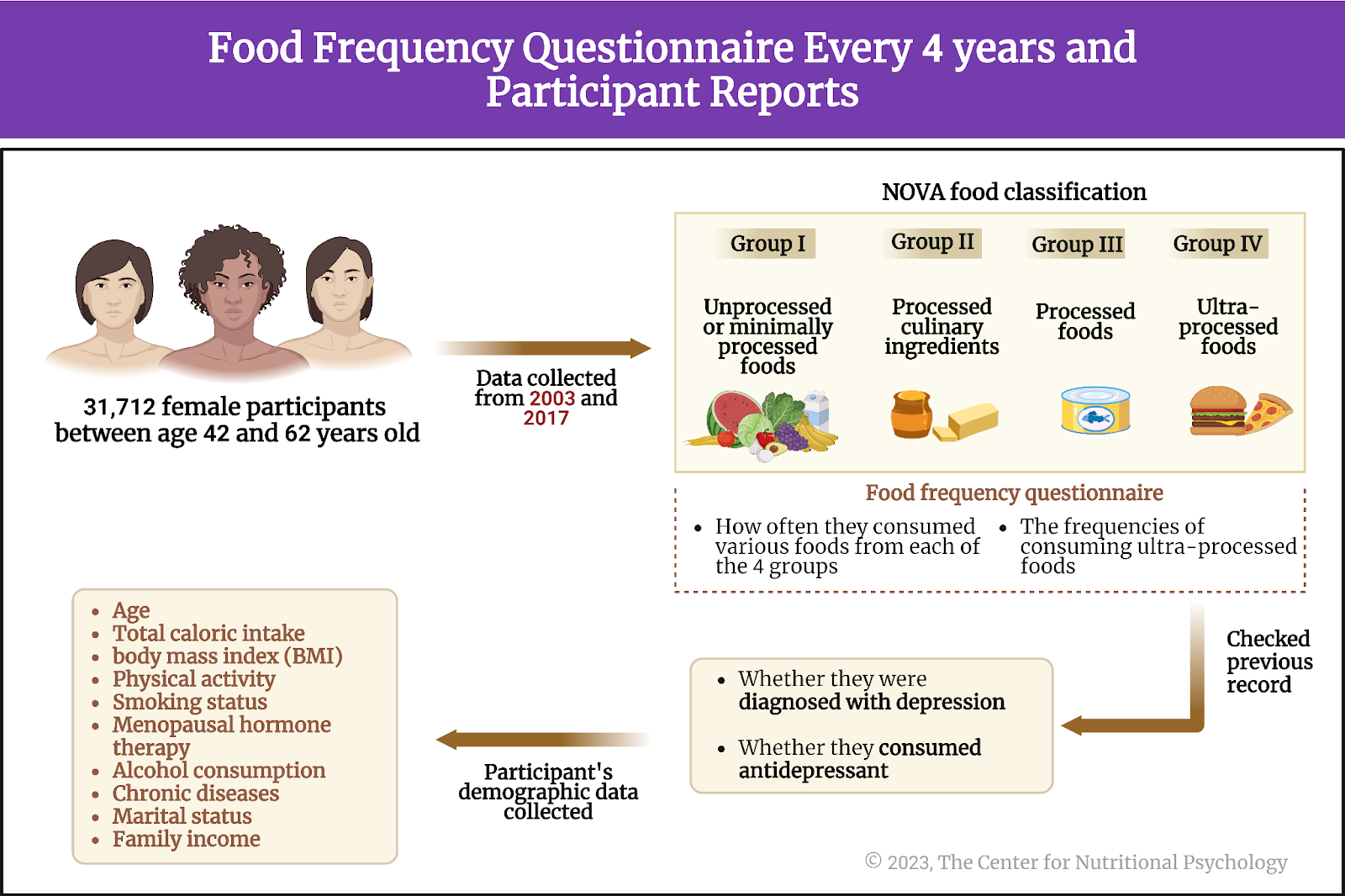

The study participants were 31,712 females in the Nurses’ Health Study II conducted between 2003 and 2017. Participants were between 42 and 62 years old at the start of the study.

Are any specific ultra-processed foods linked to depression, and does the timing of ultra-processed food consumption play a role?

The procedure

Participants completed a food frequency questionnaire based on the NOVA classification every four years. This questionnaire asked participants to report how often they consumed various foods from the four NOVA categories. The part about ultra-processed foods included questions about the frequencies of consuming ultra-processed grain foods, sweet snacks, ready-to-eat meals, fats and sauces, ultra-processed dairy products, savory snacks, processed meat, beverages, and artificial sweeteners.

Participants reported whether they were diagnosed with depression and whether they consumed antidepressants regularly. Researchers also collected data on participants’ ages, total caloric intake, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, menopausal hormone therapy, alcohol consumption, chronic diseases, marital status, family income, and other characteristics (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) every four years, and participant reports

Individuals eating more ultra-processed foods had higher body weight, smoked more, and were in poorer health

Participants who reported eating ultra-processed foods most frequently had greater body mass index, smoked more often, and suffered from diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia compared to those who reported eating ultra-processed foods less often. These individuals were also less likely to exercise regularly.

Dyslipidemia is a medical condition characterized by abnormal levels of lipids (fats) in the blood, typically involving elevated cholesterol and/or triglycerides, which can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Individuals frequently consuming ultra-processed foods were more often depressive

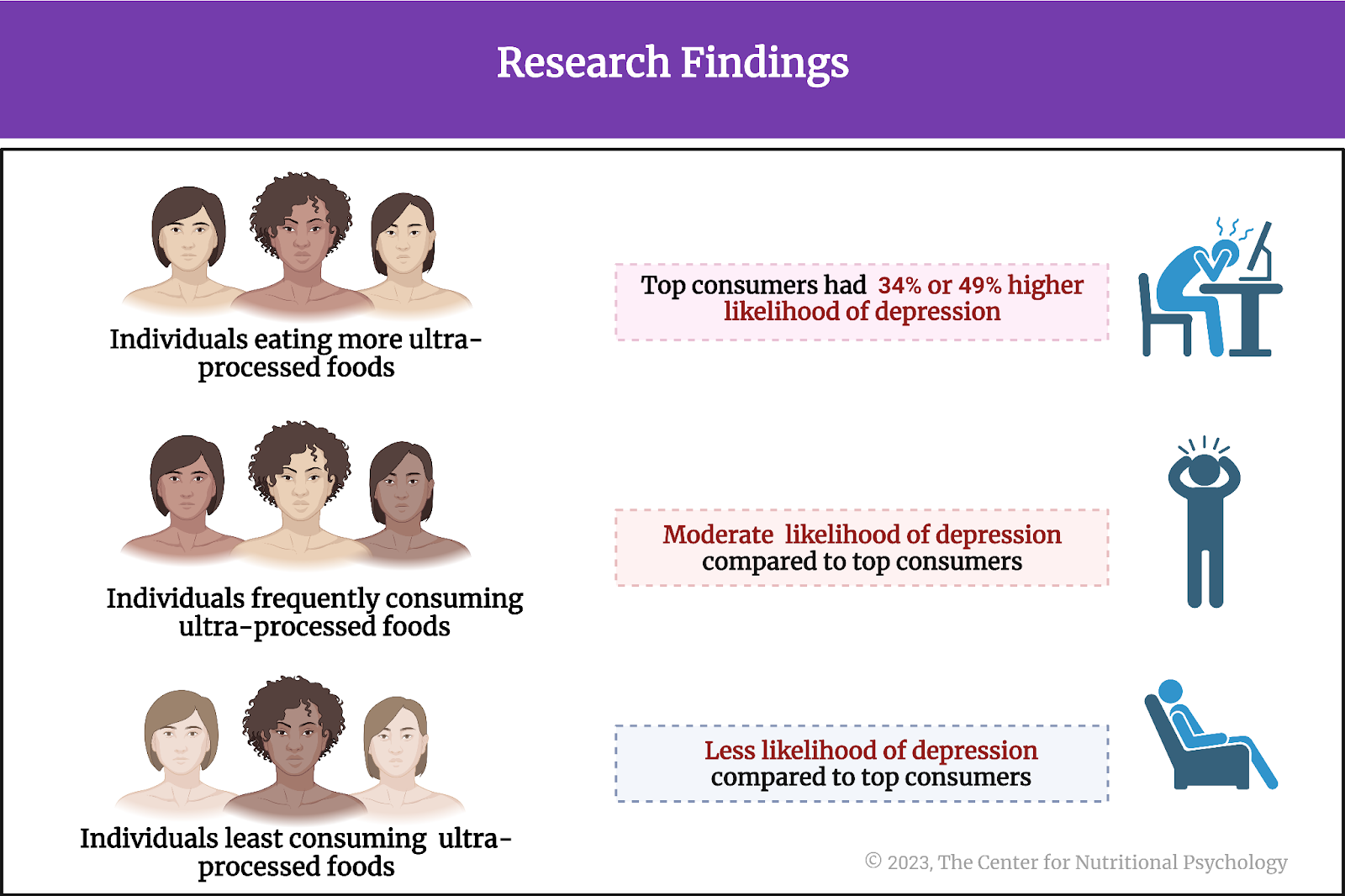

Depending on the definition of depression used, there were 2122 (using the stricter definition) or 4840 (using the broader definition) participants suffering from depression in the study. In both cases, participants who ate ultra-processed foods most frequently (the top 20% of the sample with the highest ultra-processed food consumption) were more likely to suffer from depression compared to those who ate the ultra-processed foods the least often (the bottom 20% on ultra-processed food consumption).

Participants who ate ultra-processed foods most frequently were more likely to suffer from depression than those who ate ultra-processed foods least often

Depending on the definition of depression, the top consumers of ultra-processed foods had a 34% or 49% higher likelihood of depression compared to participants who consumed these types of food the least. This finding held when study authors considered various other factors and calculated the association between ultra-processed food consumption at one point and depression four years later (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Research findings

The top consumers of ultra-processed foods had a higher likelihood of depression than participants who consumed these types of food the least

Sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners are the ultra-processed foods most strongly linked with depression

Next, the study authors explored which ultra-processed foods are most linked with depression. Are all types of ultra-processed foods equally associated with depression, or is the high consumption of some specific types of ultra-processed foods linked with a higher likelihood of depression?

Analyses showed that only high consumption of artificially sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners is associated with an increased likelihood of depression. These findings, however, don’t necessarily imply that all other UPFs consumed in the longitudinal study are exempt from having undesired effects on psychological well-being.

Analyses showed that only high consumption of artificially sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners is associated with an increased likelihood of depression

Additional analyses indicated that individuals who reduced their intake of ultra-processed foods by at least three servings per day were at a lower risk of depression compared to individuals with a relatively stable intake of these foods in each four-year period.

Conclusion

Overall, the study results suggest that frequent intake of ultra-processed foods is associated with an increased risk of depression. This is particularly the case with high intake of artificially sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners. While the nature of this association remains unknown, the large number of participants involved in this study and the fact that the association held across multiple years makes these findings particularly strong.

Given the current increase in the number of people suffering from depression in many world countries (e.g., Steffen et al., 2020; Weinberger et al., 2018) and also the increase in ultra-processed foods consumption (Monteiro et al., 2019; Samuthpongtorn et al., 2023), these findings could be used to inform policymakers and the general public about the importance of healthy food choices and how seemingly innocuous dietary decisions may have long-lasting health consequences.

The paper “Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression” was authored by Chatpol Samuthpongtorn, Long H. Nguyen, Olivia I. Okereke, Dong D. Wang, Mingyang Song, Andrew T. Chan, and Raaj S. Mehta.

References

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. In Public Health Nutrition (Vol. 22, Issue 5, pp. 936–941). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Moubarac, J. C., Levy, R. B., Louzada, M. L. C., & Jaime, P. C. (2018). The un Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutrition, 21(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000234

Samuthpongtorn, C., Nguyen, L. H., Okereke, O. I., Wang, D. D., Song, M., Chan, A. T., & Mehta, R. S. (2023). Consumption of Ultraprocessed Food and Risk of Depression. JAMA Network Open, 6(9), e2334770. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34770

Steffen, A., Thom, J., Jacobi, F., Holstiege, J., & Bätzing, J. (2020). Trends in the prevalence of depression in Germany between 2009 and 2017 based on nationwide ambulatory claims data. Journal of Affective Disorders, 271, 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2020.03.082

Weinberger, A. H., Gbedemah, M., Martinez, A. M., Nash, D., Galea, S., & Goodwin, R. D. (2018). Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychological Medicine, 48(8), 1308–1315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002781

Leave a comment