Are Hunger Cues Learned in Childhood?

Editor’s Note: Hunger is often thought of as something that we just know. This study suggests instead that hunger is learned from one’s parents.

A study on a group of Australian students and their caregivers examined whether hunger cues our body uses to create the subjective feeling of hunger, might be something that is learned in childhood. Results showed a substantial association between how students and their primary caregivers experience hunger. This might indicate that how we experience hunger is indeed learned in childhood by caregivers (Stevenson et al., 2023). The study was published in Developmental Psychobiology.

The way we experience hunger is learned in childhood from caregivers

When do we get hungry?

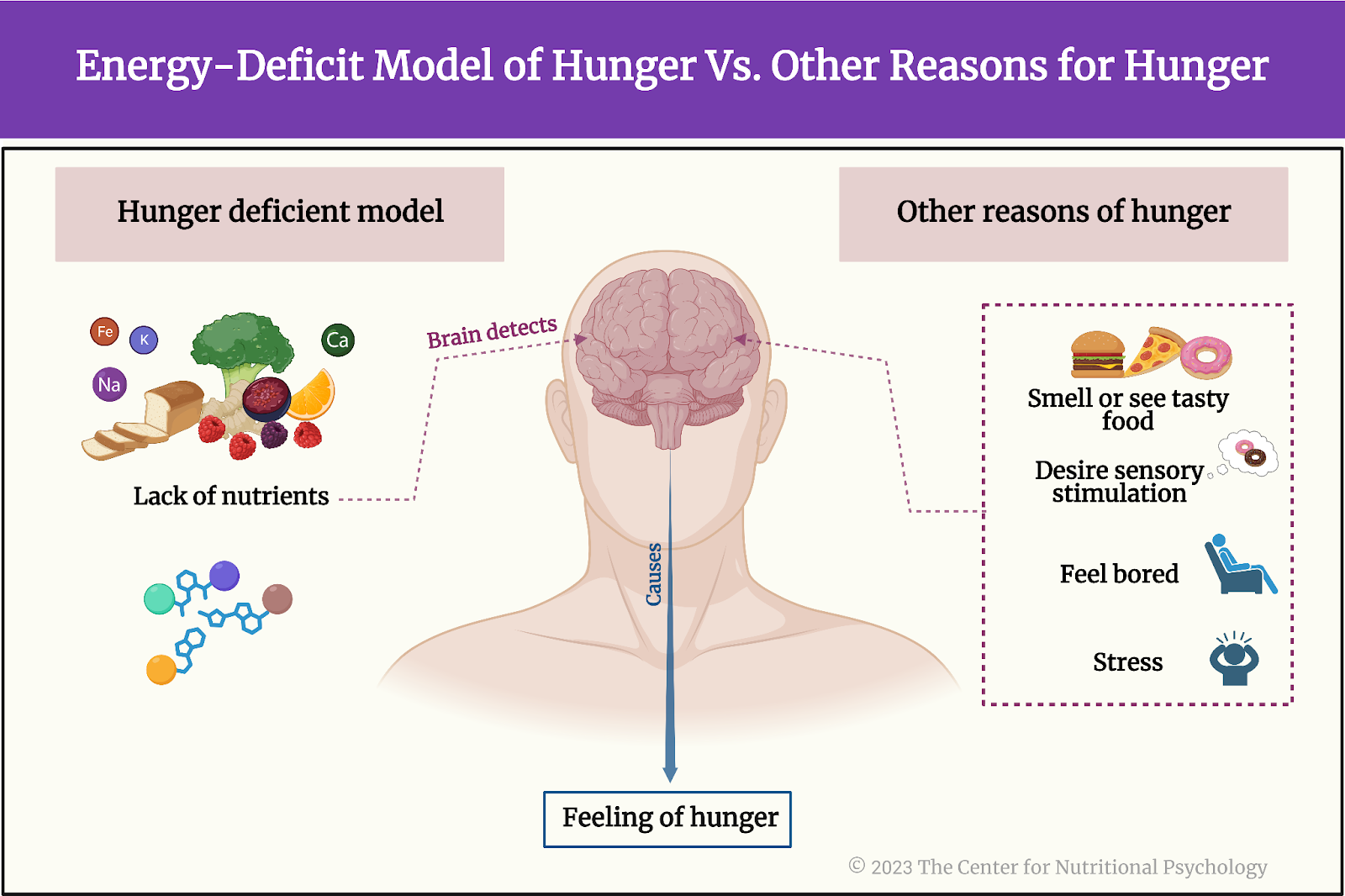

People eat when they feel hungry. The sensation of hunger motivates individuals to seek food and ingest it. For a long time, scientists and the general public believed that we feel hungry when our brain detects that certain nutrients are lacking in the body. Views such as these are called the energy-deficit models of hunger (Stevenson et al., 2023).

However, studies in the past century, particularly those in the last decades, revealed that experiences of hunger need not be a consequence of lacking nutrients. Humans and many animals can experience hunger when they smell or see tasty food, when they feel bored or desire sensory stimulation (McKiernan et al., 2008), or when they are under stress (Levine & Morley, 1981) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Energy-deficit model of hunger vs. other reasons for hunger

Hunger can be learned

Studies indicate that individuals (but also animals) can learn to expect food at certain places and at certain times. Human daily rhythms of psychological processes (circadian rhythms) are typically adjusted to having three meals per day. However, our body can also learn to expect a different number of daily meals at different times. This expectation will then trigger hunger at those times without much link to energy needs (Isherwood et al., 2023).

Our body can learn to expect a different number of daily meals and at different times

Two processes of hunger

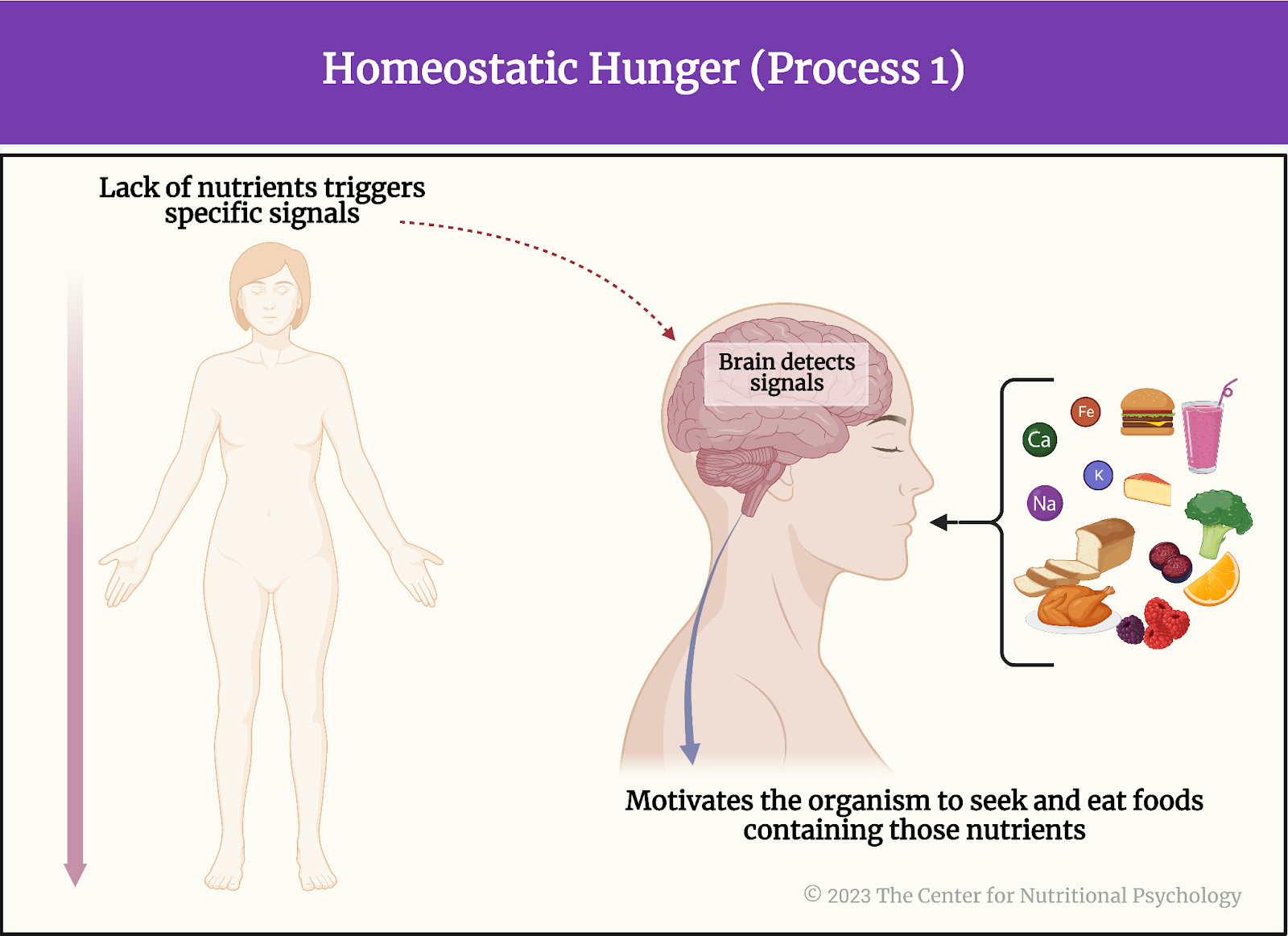

Some scientists propose that there might be two different processes responsible for hunger. According to this concept, one of these processes is centered around acquiring nutrients the body requires. Lack of specific nutrients triggers specific signals leading to the experience of hunger that motivates the organism to seek and eat foods containing those nutrients. This process is called homeostatic hunger. It describes the traditional view about how hunger develops (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Homeostatic hunger (Process 1)

The other process is appetite (see Figure 3). It arises from the learned associations between various cues for food and their consequences. For example, I see a package of chocolate. I know from previous experience that if I open it, there will be chocolate inside. I also know that if I eat the chocolate, I will feel its pleasant taste in my mouth. Due to all this, when I see chocolate, I start feeling an appetite for chocolate.

Figure 3. Appetite (Process 2)

Is homeostatic hunger real?

While scientific studies thoroughly explored and documented the processes of appetite, several authors in recent decades expressed skepticism about the workings of homeostatic hunger and its very existence. These authors note that the energy intake of a single meal is practically negligible compared to the body’s total energy reserves.

The body utilizes a complex regulation system that ensures body tissues receive enough nutrients even if a meal or several meals are missed. Hunger regulation mechanisms, on the other hand, often seem to be more about accounting for the limited capacity of the gut and adapting to the physiological challenges and hindrance of other activities that digesting food represents than about the provision of energy (Rogers & Brunstrom, 2016; Stevenson et al., 2023). For example, we will likely not feel hungry while doing intense physical work. The feeling of hunger will come only after we take a break or reduce the activity level. With these and other arguments in mind, these authors claim that the feeling of hunger might not have anything to do with the body’s short-term energy needs (Rogers & Brunstrom, 2016).

The feeling of hunger might not have anything to do with the body’s short-term energy needs at all (Rogers & Brunstrom, 2016)

The current study

Study author Richard J. Stevenson and his colleagues wanted to test the hypothesis that food sensations are learned. A recent study found that rat pups cannot respond adequately to food deprivation until they have encountered food and eaten in that state (Changizi et al., 2002). In other words, rat pups learn that eating food will produce rewarding consequences when they feel the sensations we interpret as hunger.

But does that work similarly in humans? Study authors believe so. They state that parenting might be important for teaching children the meaning of hunger. This likely happens during the weaning period and onward.

Parenting might be important for teaching children the meaning of hunger

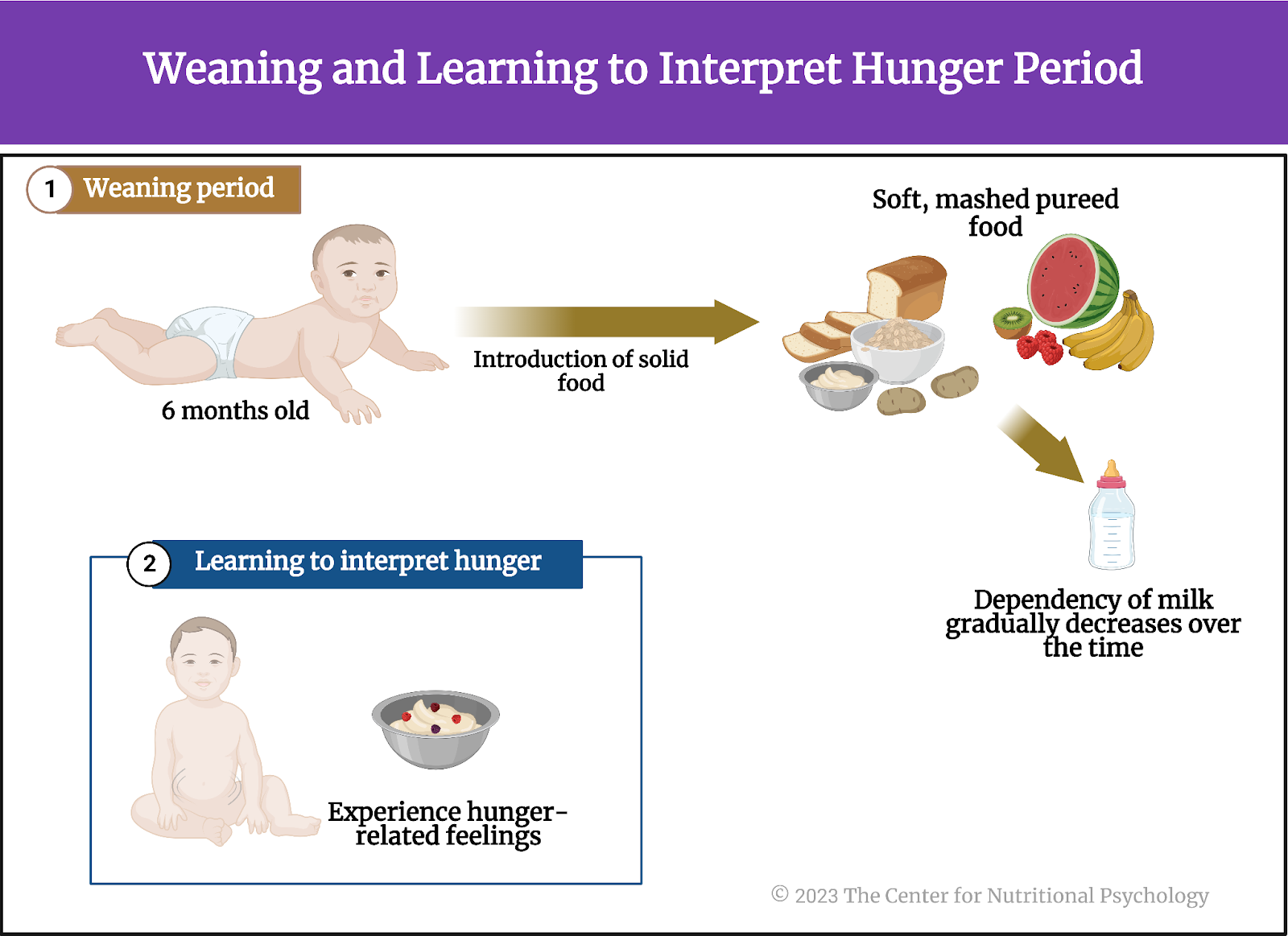

The weaning period

The weaning period is when caregivers gradually introduce solid foods into a baby’s diet and reduce its dependency on breast milk or formula as the primary source of nutrition. This transition typically begins when a baby is around six months old, although the timing can vary depending on the baby’s development and the recommendations of healthcare professionals.

During the weaning period, parents and caregivers start offering the baby a variety of soft, mashed, or pureed foods in addition to breast milk or formula. The goal is to expose the baby to different tastes and textures while ensuring it receives the nutrients needed for healthy growth and development. Over time, solid foods gradually replace some of the milk feeds.

Learning to interpret hunger

It is in this period that children likely learn the meaning of hunger. Occasionally, they experience hunger-related feelings (e.g., a tummy rumble). On some occasions, this feeling will be followed by food. On others, it would not be. The child will note that when these sensations are followed by food, the food will taste good, and they will feel good after eating it (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Weaning and learning to interpret hunger

Once they have learned this, they will likely be resistant to change because of the nature of the learning process. This learning would likely persist into adulthood as a pattern of internal signals linked to eating. These patterns of signals would differ between individuals but are likely more similar to the pattern of one’s primary caregiver (the person they learned it from) than to that of a stranger.

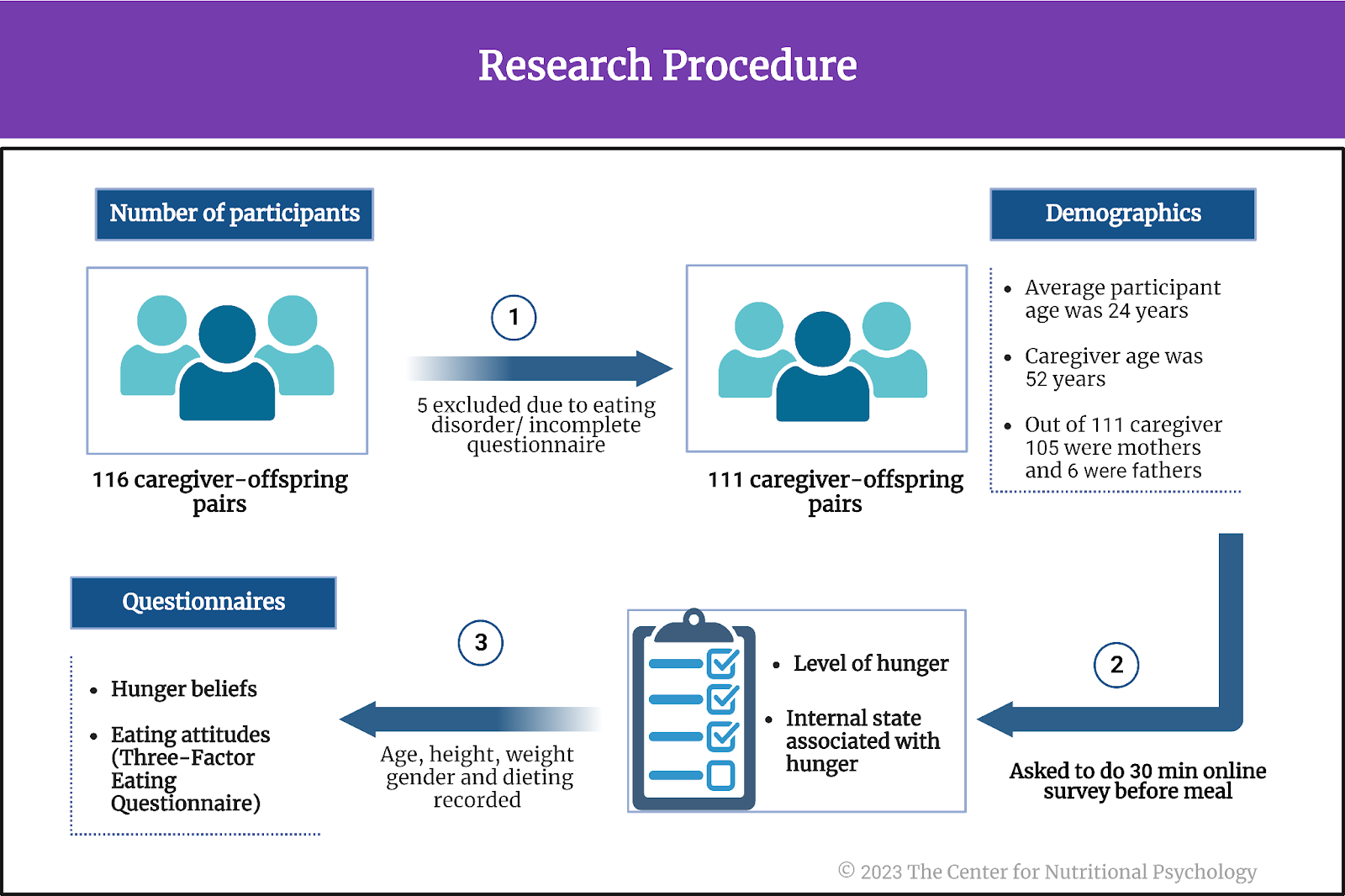

The procedure

To test this, the study authors asked 116 caregiver-offspring pairs to complete a hunger survey. The “offspring” were first-year psychology students, and the “caregiver” was the person who primarily cared for the student when he/she was a child. The study authors excluded five pairs of participants because they failed the check questions in the survey or suffered from an eating disorder. Data from a total of 111 pairs remained for the analysis. The average age of student participants (“the offspring”) was 22 years. It was 52 for the primary caregivers. One hundred and five primary caregivers were mothers, and 6 were fathers.

After they agreed to participate in the study, researchers asked both offspring and their caregivers to complete a 30-minute online survey. They instructed them to do this 30 minutes before eating a main meal. The survey first asked respondents about their current level of hunger and continued with questions focusing on different internal states that participants associated with hunger.

Additionally, participants completed assessments of hunger beliefs (a questionnaire created by study authors) and eating attitudes (the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire). Before taking the survey, students reported their age, height, weight, gender, and whether they were currently dieting. Students completed the survey before their caregivers (See Figure 5).

Figure 5. Research Procedure

Participants were moderately hungry while they were doing the survey

The median time since the last meal during the survey was 2-4 hours. This was the case both with offspring and their caregivers. Both groups of participants reported feeling a moderate urge to eat at the time of the survey. This urge was a bit more pronounced in offspring (students). Both groups reported that they could eat moderate food at that point. Overall, offspring and their caregivers were similarly hungry when they were doing the survey.

Caregivers and offspring tended to give similar responses to the hunger survey

The study authors found a medium-strength association between the responses of offspring and their caregivers on the food survey. While their responses were far from identical, there was quite a bit of similarity—much more than could be expected based on random chance.

Offspring report experiencing hunger signals more intensely than caregivers

The researchers used statistical procedures to divide hunger survey questions into several groups based on hunger signals participants tended to report similarly. They then calculated the reported intensity of those groups of signals. Results showed that the rankings of intensities of these signals were the same for offspring and caregivers.

However, on average, offspring reported experiencing the same hunger signals more intensely than their caregivers. The most intensely experienced hunger signals were empty stomachs and fatigue. Full stomach and positive anticipation were the least often seen as signaling hunger.

Offspring reported being more prone to uncontrolled and emotional eating and less prone to restrained eating than their caregivers. Additional analysis showed that when offspring and their caregivers believed more in homeostatic hunger (i.e., hunger being an indicator that the body needs energy), when offspring was more prone to uncontrolled eating, and when the caregiver had a greater body mass index, the responses of offspring and their caregiver to the hunger survey tended to be more similar (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Different parental beliefs about hunger

Conclusion

Overall, the study supported the hypothesis that hunger sensations, what sensations to interpret as hunger, are indeed learned. The fact that responses about the sensations one interprets as hunger were similar between offspring and their caregiver shows that this might indeed be something that individuals learn from their caregivers in childhood and persists without much change into adulthood.

Parent beliefs about the cause of hunger influenced what they teach their children, implying that genetics are not the sole driver of parent-child similarity

These findings may have important implications for preventing eating disorders and obesity. If interpreting sensations from the body as hunger is learned in early childhood along with what to do about those sensations, there might be a link between these learnings and later eating disorders, including the current worldwide obesity pandemic (Wong et al., 2022). It might also turn out that the development of these disorders can be mitigated or even completely prevented by simply changing what the current and future children learn about interpreting hunger sensations and how to deal with them.

The paper “The development of interoceptive hunger signals” was authored by Richard J. Stevenson, Johanna Bartlett, Madeline Wright, Alannah Hughes, Brayson J. Hill, Supreet Saluja, and Heather M. Francis.

References

Changizi, M. A., McGehee, R. M. F., & Hall, W. G. (2002). Evidence that appetitive responses for dehydration and food-deprivation are learned. Physiology and Behavior, 75(3), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00660-6\

Isherwood, C. M., van der Veen, D. R., Hassanin, H., Skene, D. J., & Johnston, J. D. (2023). Human glucose rhythms and subjective hunger anticipate meal timing. Current Biology, 33(7), 1321-1326.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.005

Levine, A. S., & Morley, J. E. (1981). Stress-induced eating in rats. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 241(1), R72–R76.

McKiernan, F., Houchins, J. A., & Mattes, R. D. (2008). Relationships between human thirst, hunger, drinking, and feeding. Physiology & Behavior, 94(5), 700. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2008.04.007

Rogers, P. J., & Brunstrom, J. M. (2016). Appetite and energy balancing. Physiology & Behavior, 164, 465–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2016.03.038

Stevenson, R. J., Bartlett, J., Wright, M., Hughes, A., Hill, B. J., Saluja, S., & Francis, H. M. (2023). The development of interoceptive hunger signals. Developmental Psychobiology, 65(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.22374

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC00

Leave a comment