What Makes Us Like or Dislike Specific Foods?

Listen to this Article

- In an online experiment published in Appetite, participants rated various characteristics of foods, including energy density, level of processing, and carbohydrate-to-fat ratio.

- Results showed that carbohydrate-to-fat ratio and taste were the primary determinants of food liking and the desire to eat.

- Contrary to findings from previous studies, the level of processing was not linked to either the desire to eat the food or its taste ratings.

Have you ever wondered what makes us like and want to eat certain foods while disliking others? Most people will say that they like tasty food when asked this question. But what makes some foods tastier than others? Many scientific studies explored this question.

What makes some foods tastier than others?

Ultraprocessed foods and obesity

Scientists first studied this question in the context of the obesity pandemic currently plaguing the world (Wong et al., 2022). Their findings showed that many overweight people tend to eat lots of ultraprocessed foods. Ultraprocessed foods have undergone extensive processing and often contain additives to improve their taste and appeal (Monteiro et al., 2019). Researchers found that some components of ultraprocessed foods trigger neural processes similar to those found in various addictions, creating intense desires for those foods (Gearhardt et al., 2023; Hedrih, 2023).

Some components of ultraprocessed foods trigger neural processes similar to those found in various addictions, creating intense desires for those foods

Fat, carbohydrates, and food reward processing in the brain

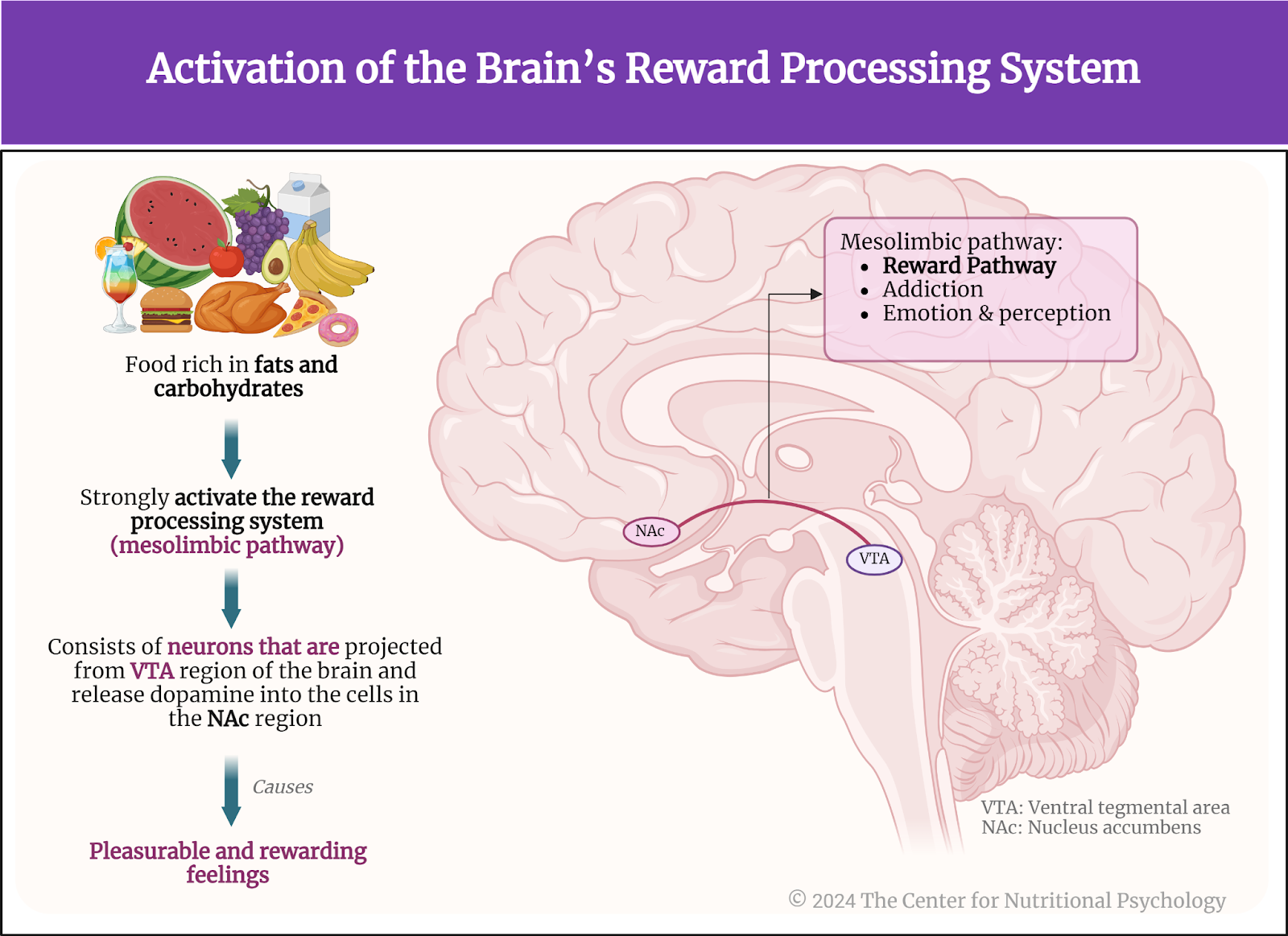

Other studies indicate that foods rich in fat and carbohydrates create the strongest activation of the reward processing system in the brain, the system of neural circuits that produces the pleasurable and rewarding feelings we experience when we eat something tasty (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Activation of the brain’s reward processing system

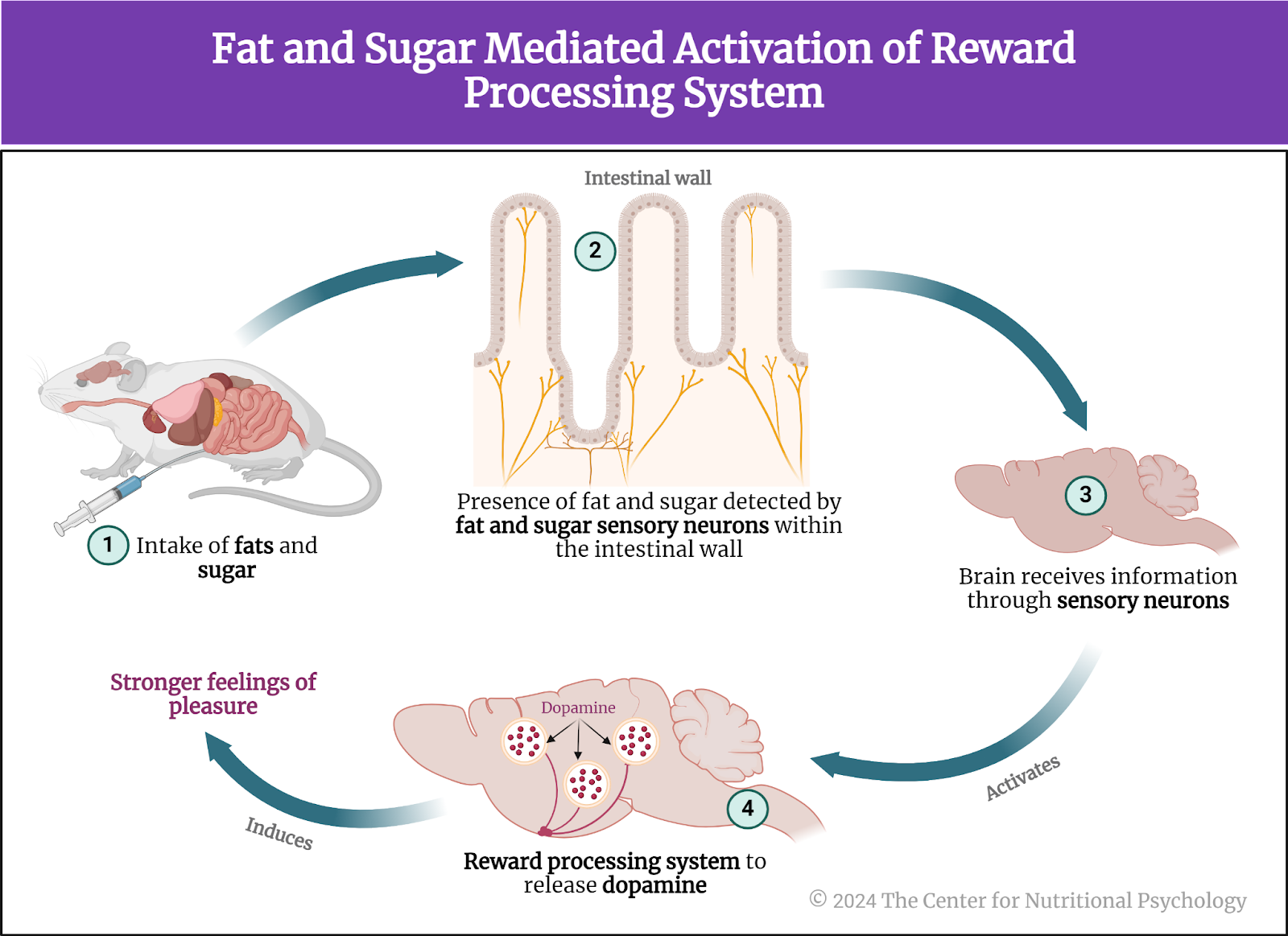

A recent study on mice showed that our brain has separate neural reward circuits for sugars and fats. Due to this, foods that are both fatty and sweet trigger both of these circuits simultaneously resulting in stronger feelings of pleasure than what foods that are just sweet or just fatty could produce (Hedrih, 2024; McDougle et al., 2024). Research has shown for quite some time that feeding mice a fat-rich diet (mouse food already contains carbohydrates) will cause them to overeat and become obese (Ikemoto et al., 1996) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fat and Sugar Mediated Activation of Reward Processing System

The current study

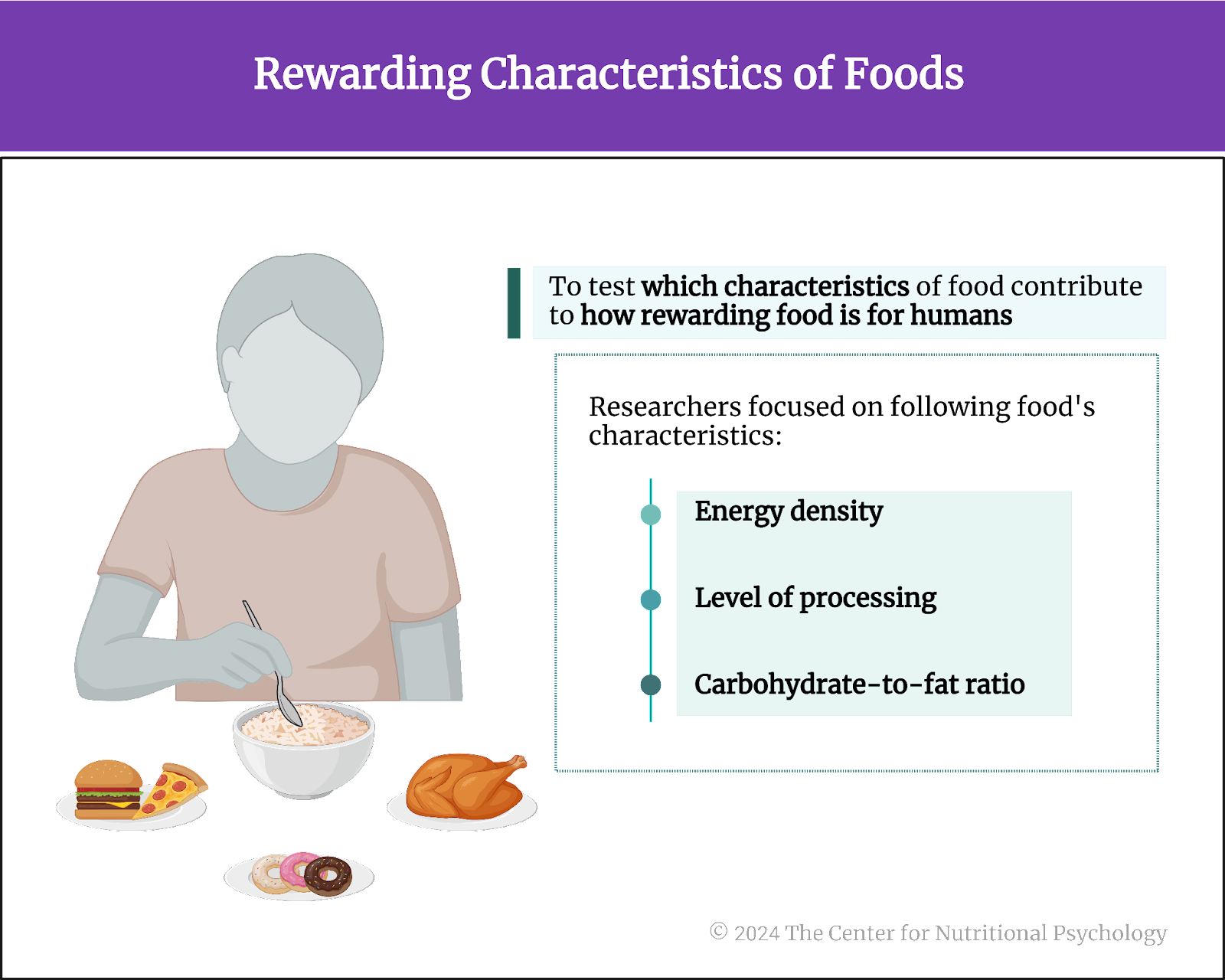

Study author Peter J. Rogers and his colleagues wanted to test which characteristics of food contribute to how rewarding the food is for humans (Rogers et al., 2024). They focused on 1) the energy density of food, 2) its level of processing, and 3) the carbohydrate-to-fat ratio (see Figure 3). The energy density of food refers to the amount of energy (calories) in a given weight of food, typically expressed in calories per gram.

Figure 3. Rewarding characteristics of foods

The procedure

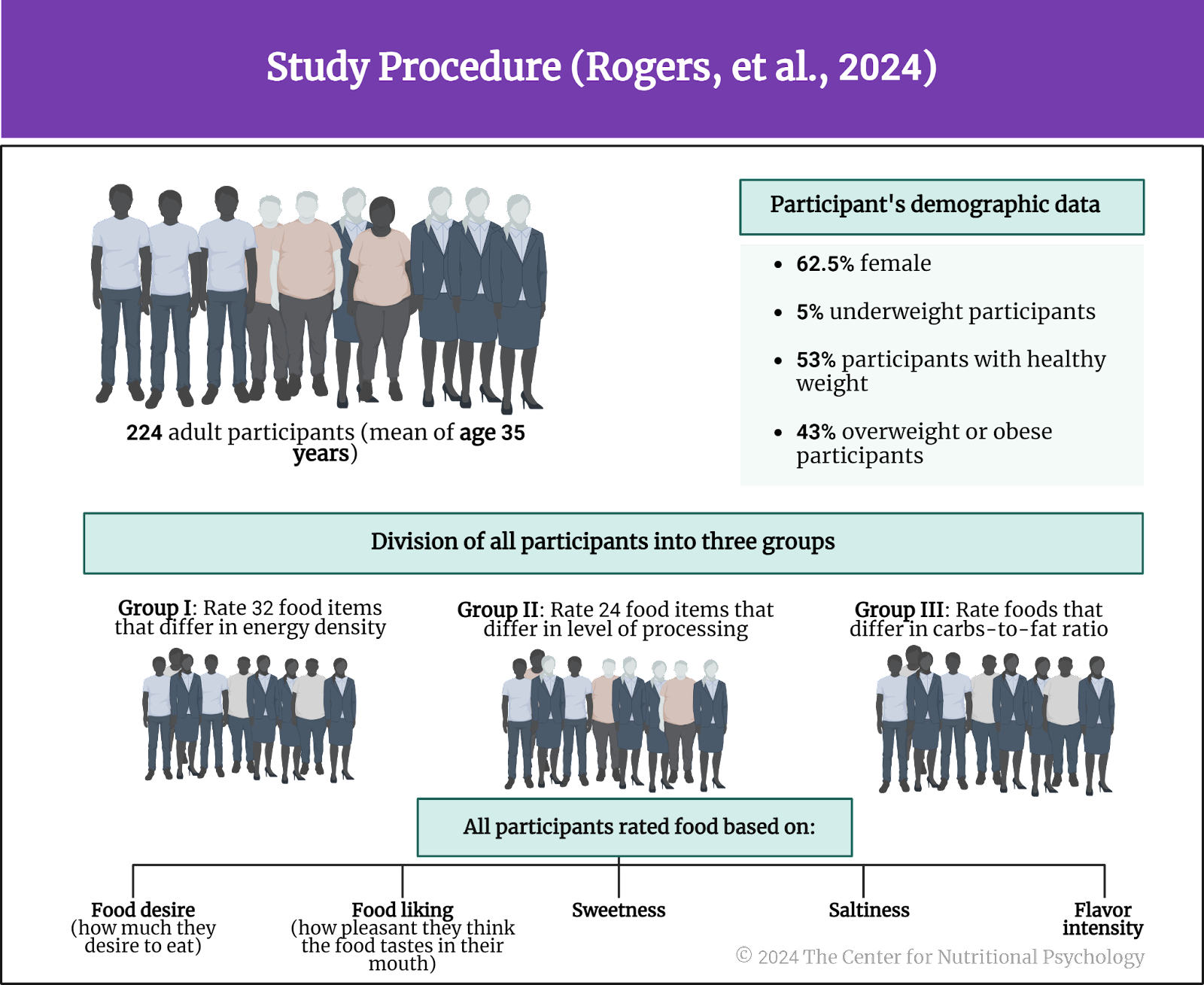

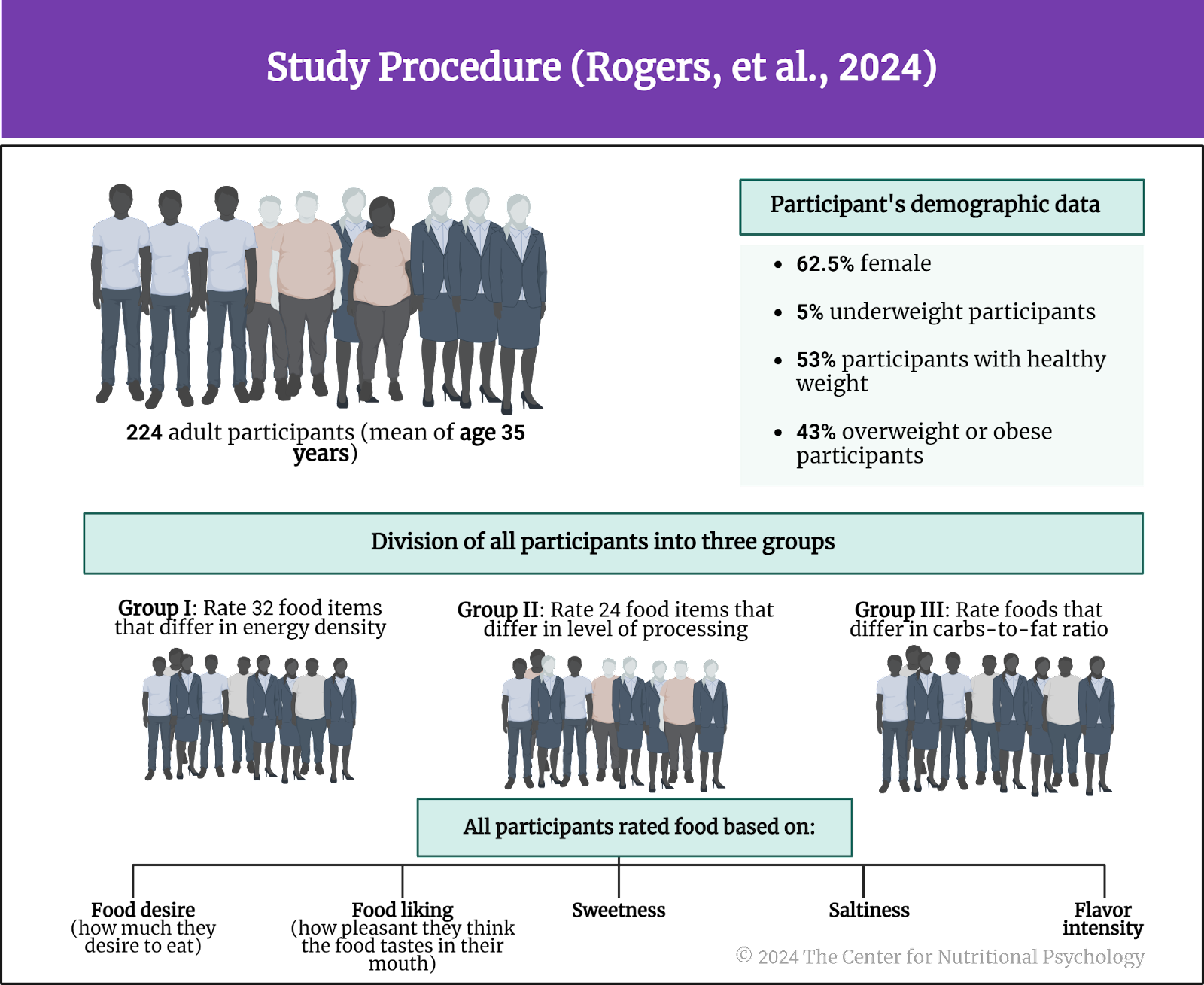

The authors recruited 224 adult participants through social media. Participants were required not to be vegetarians or vegans and to be familiar with the food they would be rating. The mean age of participants was 35 years. 62.5% of them were female. 5% of participants were underweight, 53% had a healthy weight, and 43% were overweight or obese.

The study authors divided these participants into three groups. One group would rate a set of food items differing in energy density (32 foods), and the second group would do that for foods differing in the level of processing (24 foods). In contrast, the third group rated foods differing in their carbohydrate-to-fat ratio (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Study Procedure (Rogers et al., 2024)

Participants rated their assigned food set on food reward (how much they desire to eat), liking (how pleasant they think the food tastes in their mouth), sweetness, saltiness, and flavor intensity.

Food items were presented as pictures of a 50-gram portion on a light-beige colored plate. To ensure that participants were somewhat hungry at the time of the study, the authors instructed them not to eat anything for 2 hours before the study. Participants were supposed to imagine taking a bite of the food shown in the picture and tasting it. They would then provide the rating.

Foods presented in the energy density group included (in increasing order of energy density) fresh apple slices (the lowest energy density), a boiled egg, Edam cheese slices, crisps, and original Pringles (the highest energy density). Foods in the level of processing set included avocado (no processing), Parma ham, and wine gums (a type of gummy candy, the highest level of processing). The carbohydrate-to-fat ratio group included dried apple slices (high share of carbohydrates, little fat), Cornish dairy ice cream (moderate amounts of both fats and carbohydrates), and Frankfurter sausage (high in fats, little carbohydrates).

Participants liked very energy-dense foods and medium-processed foods the most

Results showed that participants liked and wanted to eat energy-dense foods the most. However, the least liked foods were not those with the lowest energy density but foods with medium energy density levels. The situation with food rewards was the same. Taste intensity tended to increase with energy density. Participants rated the least energy-dense foods as having the least intensive taste.

In the set of foods that differed by the level of processing, participants found processed, but not ultraprocessed foods, to be the most to their liking, the most rewarding, and with the highest taste intensity. Minimally processed foods received the lowest ratings. However, participants found unprocessed foods even more rewarding (i.e., they wanted to eat them more) than medium-processed foods.

Participants found processed, but not ultraprocessed foods, to be the most to their liking, the most rewarding, and with the highest taste intensity

Foods containing both fats and carbohydrates received the best ratings

In the carbohydrate-to-fat ratio food group, participants found foods containing roughly equal amounts of carbohydrates and fats to be the most to their liking and the most rewarding. Foods consisting solely of carbohydrates or solely of fats tended to receive the worst ratings. Differences in food intensity in this group of food items were less pronounced.

The study authors developed a statistical model to predict food reward and liking and included various food constituents, intensity of taste, and carbohydrate-to-fat ratio. Statistical tests showed that participants liked foods containing roughly equal amounts of fats and carbohydrates, with the most intense taste and low fiber content. They also found such foods the most rewarding (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Research findings

Conclusion

The study showed that people find foods with intensive taste containing roughly equal amounts of fats and carbohydrates the most to their liking and the most rewarding. Contrary to previous studies, participants did not find ultraprocessed foods the most rewarding or like them the most. This shows that in this study, it was not the level of processing that determined how liked and rewarding a food item would be.

These findings can help researchers and health practitioners better understand the psychological values of different food items. This might allow for better diets and improved obesity prevention programs.

The paper “Evidence that carbohydrate-to-fat ratio and taste, but not energy density or NOVA level of processing, are determinants of food liking and food reward” was authored by Peter J. Rogers, Yeliz Vural, Niamh Berridge-Burley, Chloe Butcher, Elin Cawley, Ziwei Gao, Abigail Sutcliffe, Lucy Tinker, Xiting Zeng, Annika N. Flynn, Jeffrey M. Brunstrom, and J.C. Brand-Miller.

References

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Hedrih, V. (2023). Scientists Propose that Ultra-Processed Foods be Classified as Addictive Substances. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/scientists-propose-that-ultra-processed-foods-be-classified-as-addictive-substances/

Hedrih, V. (2024, February 19). Consuming Fat and Sugar (At The Same Time) Promotes Overeating, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/16563-2/

Ikemoto, S., Takahashi, M., Tsunoda, N., Maruyama, K., Itakura, H., & Ezaki, O. (1996). High-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and obesity in mice: Differential effects of dietary oils. Metabolism, 45(12), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90185-7

McDougle, M., de Araujo, A., Singh, A., Yang, M., Braga, I., Paille, V., Mendez-Hernandez, R., Vergara, M., Woodie, L. N., Gour, A., Sharma, A., Urs, N., Warren, B., & de Lartigue, G. (2024). Separate gut-brain circuits for fat and sugar reinforcement combine to promote overeating. Cell Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.014

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Rogers, P. J., Vural, Y., Berridge-Burley, N., Butcher, C., Cawley, E., Gao, Z., Sutcliffe, A., Tinker, L., Zeng, X., Flynn, A. N., Brunstrom, J. M., & Brand-Miller, J. C. (2024). Evidence that carbohydrate-to-fat ratio and taste, but not energy density or NOVA level of processing, are determinants of food liking and food reward. Appetite, 193, 107124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.107124

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005

Leave a comment