Can Social Anxiety From Humans be Transmitted to Mice?

Listen to this Article

- A study published in PNAS: Neuroscience explored whether social anxiety can be transmitted from humans to mice via gut microbiota

- Mice receiving gut microbiota from human participants with social anxiety disorder became more sensitive to social fear

- While the nonsocial behaviors of these mice remained normal, biochemical changes linked to higher levels of social fear were also detected

What is social anxiety?

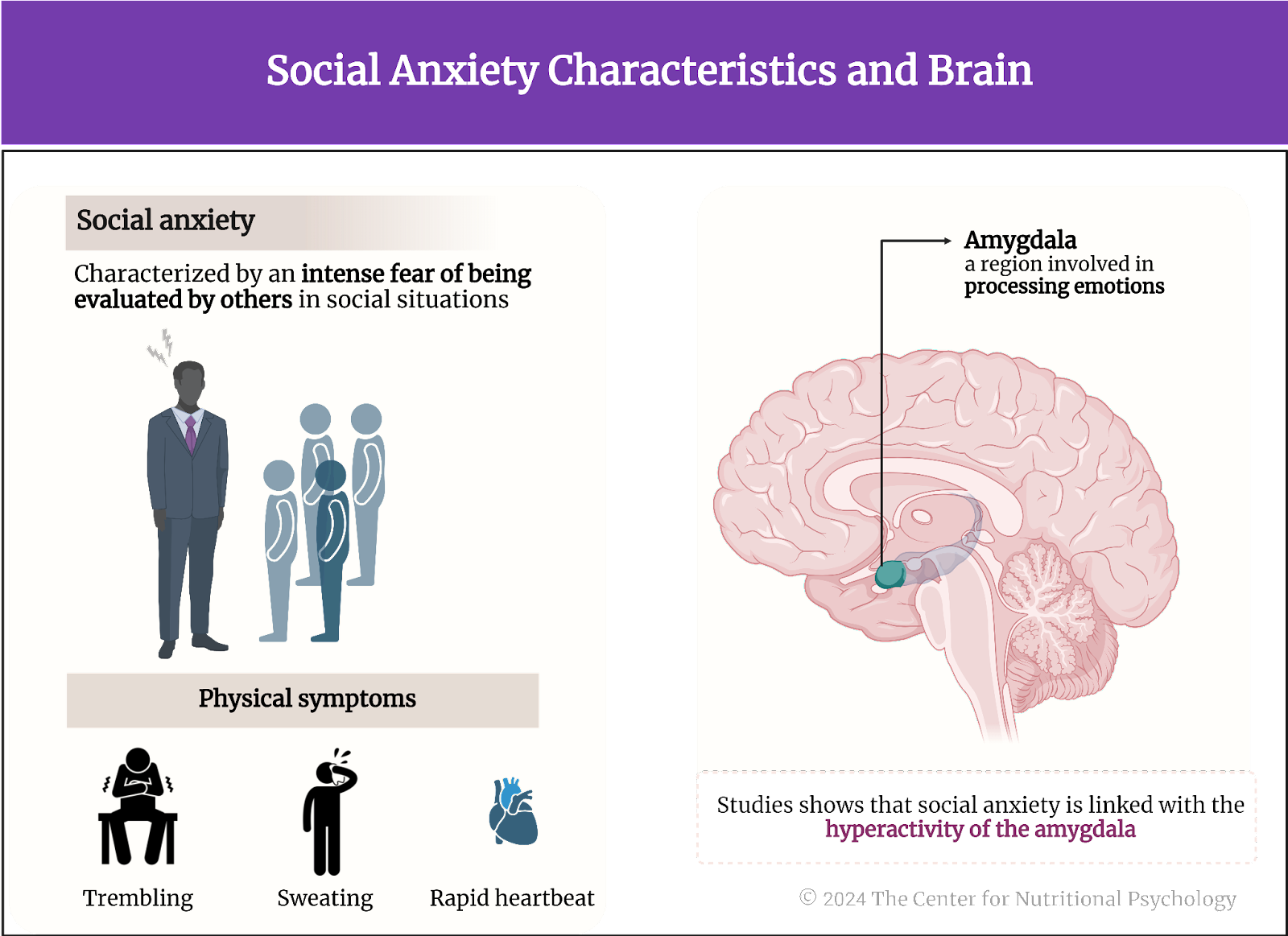

Social anxiety is a common human condition characterized by an intense fear of being evaluated by others in social situations (Morrison & Heimberg, 2013). People with social anxiety constantly worry about acting in a way that will be embarrassing or humiliating. They may even avoid social situations to prevent embarrassment. This fear can interfere with daily activities, work, and relationships. It can also lead to physical symptoms such as sweating, trembling, or a rapid heartbeat. If social anxiety reaches the level of severity where it impairs everyday functioning, it becomes a social anxiety disorder or social phobia.

Studies of brain activity link social anxiety with the hyperactivity of the amygdala region of the brain (Phan et al., 2006), a region involved in processing emotions, and with abnormalities in neural networks that use neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine (e.g., Wee et al., 2008). However, the causes of these changes remain unknown (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Social anxiety Characteristics and brain

The microbiota-gut-brain axis and social anxiety

The recent discovery of the microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA), a bidirectional pathway through which microorganisms residing in our gut can affect processes in the brain and vice versa, showed that microbiota changes can affect different biochemical processes in the brain. Study after study on the microbiota-gut-brain axis shows that gut microbiota composition is linked to various mental health symptoms, that it can regulate reward processing in the brain, craving, certain aspects of social cognition, and binge drinking (Carbia et al., 2023; García-Cabrerizo et al., 2021; V. Hedrih, 2023). Transplanting microbiota from patients with Alzheimer’s disease into rats makes rats develop cognitive impairments (Grabrucker et al., 2023; Hedrih, 2024) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Microbiota composition linked to various mental health symptoms

Transplanting microbiota from humans with Alzheimer’s disease into rats makes rats develop cognitive impairments

The current study

Recent research findings also show that the gut microbiota composition of individuals with social anxiety disorder differs from that of healthy humans. This made the author of this study, Nathaniel L. Ritz, and his colleagues wonder whether gut microbiota might have a causal role in the development of social anxiety. To test this, they conducted a study in which they transplanted the gut microbiota of individuals with social anxiety disorder and healthy individuals into the guts of mice (Ritz et al., 2024).

Study procedure

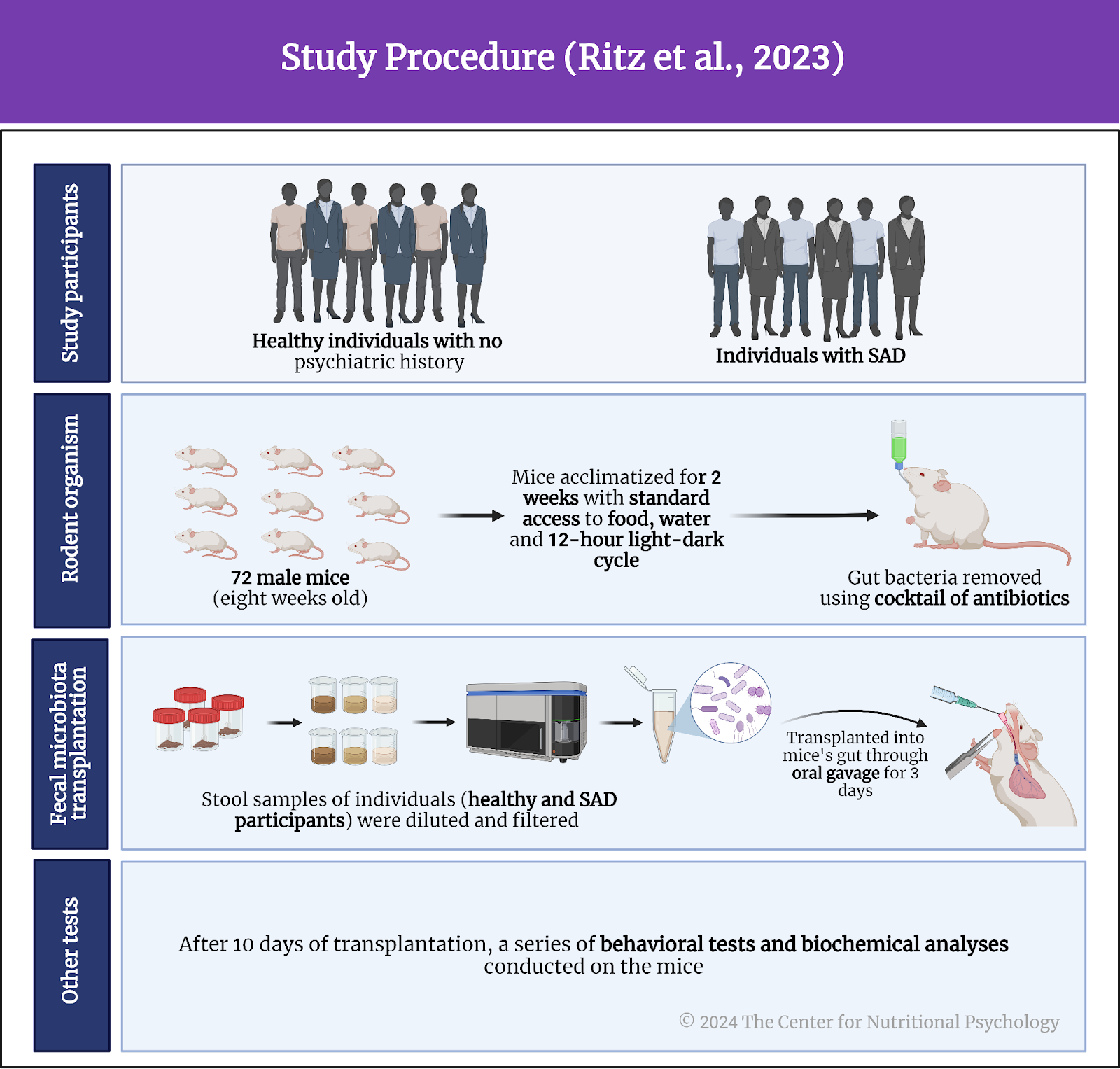

The study involved 12 human participants: 6 diagnosed with social anxiety disorder (SAD) and six healthy individuals without psychiatric history. The study authors selected the social anxiety group from participants of a previous study on the links between social anxiety and gut microbiota composition. Healthy participants came from University College Cork in Ireland. Both groups provided stool samples needed for transplantation into mice.

The study authors transplanted gut microbiota from the feces of human participants into the guts of 72 male mice. The mice were eight weeks old at the start of the study. They were acclimatized for two weeks and kept in a 12-hour light-dark cycle with free access to standard mouse food and water. Researchers then depleted mice’s gut microbiota using a strong cocktail of antibiotics (ampicillin, vancomycin, imipenem) to prepare them for human microbiota. Each mouse received microbiota from a randomly chosen human participant.

Stool samples from human participants were diluted, filtered, and inserted into the mice’s guts via oral gavage for three consecutive days. Oral gavage is a procedure where researchers use a syringe with a feeding tube to directly insert contents into the guts of mice through their mouths. Half of the mice received microbiota from individuals with social anxiety disorder, while the other half received it from healthy participants.

The study authors waited ten days after the transplantation procedure and then conducted a series of behavioral tests on the mice. They also collected stool samples of mice and conducted different biochemical analyses (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Study procedure (Ritz et al., 2023)

Gut microbiota from individuals with social anxiety differed in composition

Results showed differences in the gut microbiota composition between mice transplanted with microbiota from healthy participants and those from participants with social anxiety disorder. They differed in the abundance of three bacterial species – Bacteroides nordii, Bacteroides cellulosiyticus, and Phocaeicola massiliensi.

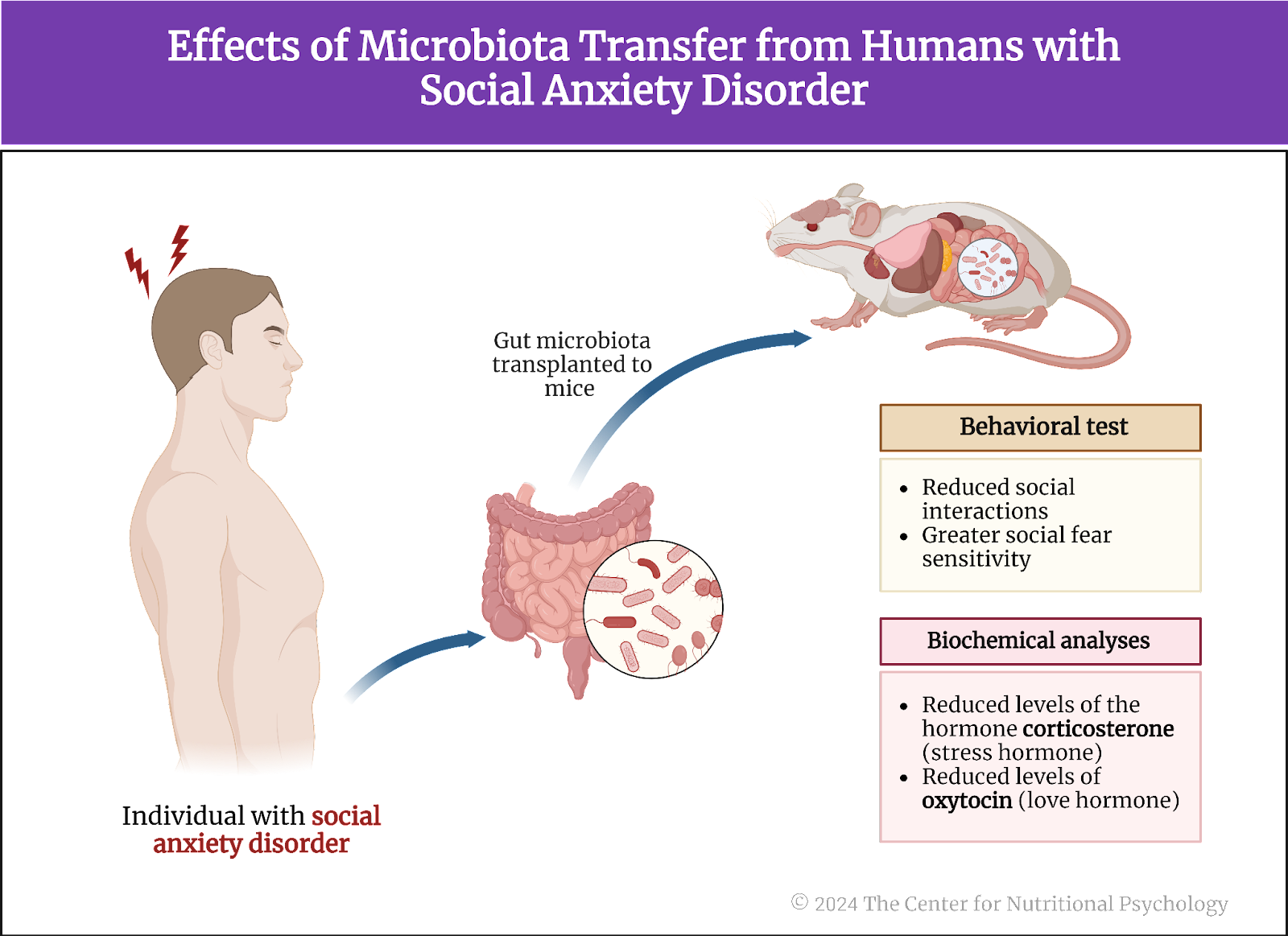

Gut microbiota from humans with social anxiety disorder induced social fear sensitivity in mice

Mice with microbiota from social anxiety disorder participants showed reduced social interactions in behavioral tests. However, their non-social exploratory behaviors did not differ from those of mice that received microbiota from healthy human participants. Based on this, the study authors concluded that transplantation of gut microbiota from humans with social anxiety disorder induced greater social fear sensitivity in these mice.

Biochemical changes also indicated heightened susceptibility to social fear

Mice that received gut microbiota from humans with social anxiety disorder had reduced levels of the hormone corticosterone. Corticosterone is a steroid hormone the adrenal cortex produces, primarily regulating stress responses, energy metabolism, immune reactions, and electrolyte balance.

They also showed reduced levels of oxytocin in a specific region of the brain (the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis) and lower activity of genes related to this neurotransmitter in other brain regions (the medial amygdala and the prefrontal cortex) (see Figure 4). Oxytocin is a hormone and neurotransmitter often called the “love hormone” due to its role in social bonding, sexual reproduction, childbirth, and maternal behaviors. Thus, its reduced levels and production make a mouse more susceptible to social fear and less motivated for social interactions.

Figure 4. Effects of microbiota transfer from humans with social anxiety disorder

Conclusion

The study showed that it is possible to induce social fear sensitivity in mice by transplanting gut microbiota from humans with social anxiety disorder (i.e., highly sensitive to social fear). These results confirm that gut microorganisms can play a causal role in the development of social fear. If future studies show that changes to gut microbiota can also reduce social anxiety (instead of increasing it), it may open the possibility of developing ways to treat social anxiety using tailor-made probiotics.

It’s possible to induce social fear sensitivity in mice by transplanting gut microbiota from humans with social anxiety disorder

The paper “Social anxiety disorder-associated gut microbiota increases social fear” was authored by Nathaniel L. Ritz, Marta Brocka, Mary I. Butler, Caitlin S. M. Cowan, Camila Barrera-Bugueño, Christopher J. R. Turkingtona, Lorraine A. Draper, Thomaz F. S. Bastiaanssen, Valentine Turpin, Lorena Morales, David Campos, Cassandra E. Gheorghe, Anna Ratsika, Virat Sharma, Anna V. Golubeva, Maria R. Aburto, Andrey N. Shkoporov, Gerard M. Moloney, Colin Hill, Gerard Clarke, David A. Slattery, Timothy G. Dinan, and John F. Cryan.

References

Carbia, C., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Iannone, F., García-cabrerizo, R., Boscaini, S., Berding, K., Strain, C. R., Clarke, G., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2023). The Microbiome-Gut-Brain axis regulates social cognition & craving in young binge drinkers. eBioMedicine, 89, 104442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104442

García-Cabrerizo, R., Carbia, C., O´Riordan, K. J., Schellekens, H., & Cryan, J. F. (2021). Microbiota-gut-brain axis as a regulator of reward processes. Journal of Neurochemistry, 157(5), 1495–1524. https://doi.org/10.1111/JNC.15284

Grabrucker, S., Marizzoni, M., Silajdžić, E., Lopizzo, N., Mombelli, E., Nicolas, S., Dohm-Hansen, S., Scassellati, C., Moretti, D. V., Rosa, M., Hoffmann, K.,

Cryan, J. F., O’Leary, O. F., English, J. A., Lavelle, A., O’Neill, C., Thuret, S., Cattaneo, A., & Nolan, Y. M. (2023). Microbiota from Alzheimer’s patients induce deficits in cognition and hippocampal neurogenesis. Brain. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad303

Hedrih, V. (2023, September 2). Gut Microbiota’s Role in Mental Health: The Positives and Negatives. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/how-your-gut-microbiota-is-linked-to-both-positive-and-negative-aspects-of-mental-health/

Hedrih, V. (2024, January 29). Can Symptoms of Alzheimer’s be Transferred to Rats via the Gut Microbiota of Alzheimer’s Patients? CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/can-symptoms-of-alzheimers-be-transferred-to-rats-via-the-gut-microbiota-of-alzheimers-patients/

Morrison, A., & Heimberg, R. (2013). Social Anxiety and Social Anxiety Disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185631

Phan, K. L., Fitzgerald, D., Nathan, P., & Tancer, M. (2006). Association between Amygdala Hyperactivity to Harsh Faces and Severity of Social Anxiety in Generalized Social Phobia. Biological Psychiatry, 59, 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.012

Ritz, N. L., Brocka, M., Butler, M. I., Cowan, C. S. M., Barrera-Bugueño, C., Turkington, C. J. R., Draper, L. A., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Turpin, V., Morales, L., Campos, D., Gheorghe, C. E., Ratsika, A., Sharma, V., Golubeva, A. V., Aburto, M. R., Shkoporov, A. N., Moloney, G. M., Hill, C., … Cryan, J. F. (2024). Social anxiety disorder-associated gut microbiota increases social fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(1), e2308706120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308706120

Wee, N. J. van der, Veen, J. F. van, Stevens, H., Vliet, I. M. van, Rijk, P. P. van, & Westenberg, H. G. (2008). Increased Serotonin and Dopamine Transporter Binding in Psychotropic Medication–Naïve Patients with Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder Shown by 123I-β-(4-Iodophenyl)-Tropane SPECT. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 49(5), 757–763. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.107.045518

Leave a comment