Can Our Facial Attractiveness Depend on What We Just Ate?

Listen to this Article

- A study in France published in PLOS One found that facial attractiveness can change depending on what a person eats.

- Opposite-sex raters evaluated study participants’ facial attractiveness using pictures taken two hours after breakfast.

- Facial attractiveness of both men and women was reduced after a breakfast rich in carbohydrates.

- The effects were possible due to an increase in age appearance in women and a decrease in perceived masculinity in males.

We all know that our attractiveness can change depending on the circumstances. For example, when we’re tired or after sleepless nights, we might not appear as attractive as when fresh and well-rested. This difference will primarily reflect on our face, one of the most important parts of the human body for evaluating attractiveness.

Facial attractiveness

Facial attractiveness is a highly valued trait in many cultures. It is often associated with health, youth, and symmetry, which are genetic fitness markers. From an evolutionary perspective, facial attractiveness is thought to signal good genes and reproductive potential, leading individuals to prefer mates with appealing facial features. In various cultures, attractive faces tend to be linked to social status, success, and desirability. They influence mate selection and social interactions (Little, 2021; Rhodes, 2006).

Research suggests that certain universal features, such as clear skin, balanced facial proportions, and symmetry, are consistently rated more attractive across different cultures. However, cultural differences exist, with preferences for specific facial traits varying based on societal norms and environmental factors (Zhan et al., 2021).

Facial beauty is one of the first things we notice when observing someone. Studies show that our brains need just one-tenth of a second to recognize a face and evaluate the aggressiveness and trustworthiness of a person (Shavlokhova et al., 2024; Willis & Todorov, 2006).

The beauty premium

Researchers also discuss the “beauty premium,” the phenomenon where individuals perceived as more attractive tend to receive various advantages in life. These include higher earnings, better job opportunities, and preferential treatment in social situations. This advantage is not limited to employment but can extend to other areas such as education, politics, and legal outcomes (Dossinger et al., 2019).

Researchers suggest that the beauty premium may stem from a combination of factors, including societal biases that associate physical attractiveness with positive traits and the confidence and social skills that attractive individuals may develop as a result of favorable treatment (Borland & Leigh, 2014; Mobius & Rosenblat, 2006).

But does facial beauty depend on what we have just eaten?

The current study

Study author Amandine Visine and her colleagues wanted to investigate whether refined carbohydrate intake affects facial attractiveness in young men and women. They note that Western populations started consuming much more refined carbohydrates in several previous decades than they did in earlier centuries. This shift was associated with various adverse health consequences. Some researchers proposed that it also affected facial attractiveness, but the results were inconclusive (Visine et al., 2024). This study aimed to clarify those effects.

The study procedure

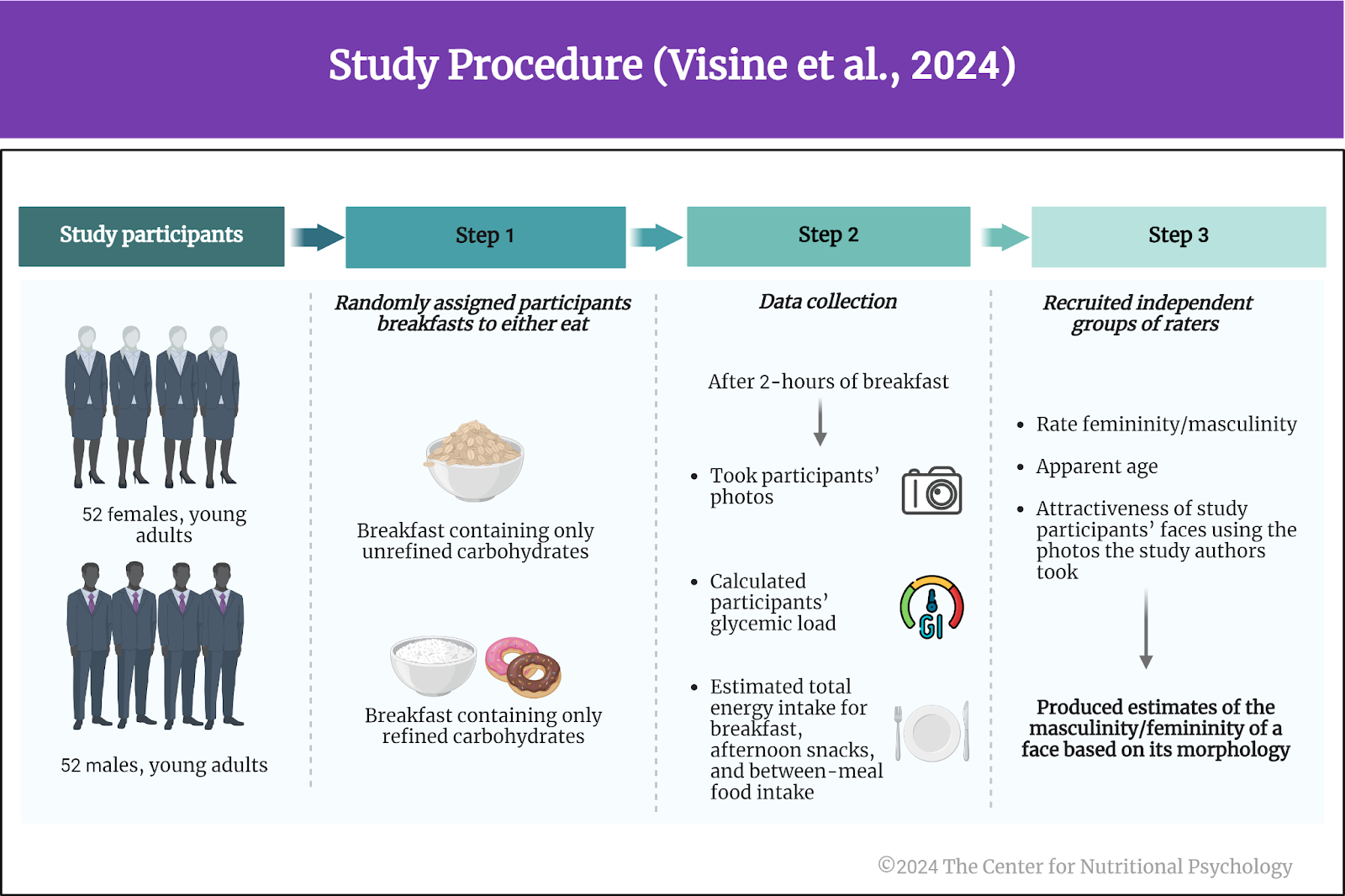

The study participants were 52 males and 52 females, young adults between 20 and 30 years of age, heterosexual, and with four grandparents of European origin. The study authors invited them for breakfast in their lab and asked them to ensure they came on an empty stomach.

In the lab, researchers randomly assigned participants to eat a breakfast containing only unrefined carbohydrates or a breakfast containing only refined carbohydrates. Both breakfasts had 500 calories. Approximately 2 hours after breakfast, the study authors took participants’ photos. On this occasion, participants also completed a dietary habits index. The study authors used these data to calculate participants’ glycemic load, which estimates the impact of food eaten on blood sugar levels. They estimated this parameter and the total energy intake for breakfast, afternoon snacks, and participants’ between-meal food intake.

After this, the study authors recruited independent groups of raters in a public place in Montpellier, France, to rate femininity/masculinity, apparent age, and attractiveness of study participants’ faces using the photos the study authors took. Raters rated the facial attractiveness of participants of the opposite sex. Seventy-seven raters rated apparent age, 150 rated perceived masculinity/femininity, and 252 raters rated attractiveness. Independent of this, the study authors used computer software to produce estimates of the masculinity/femininity of a face based on its morphology (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Procedure (Visine et al., 2024)

Eating breakfast comprised of refined carbohydrates reduced facial attractiveness in both men and women

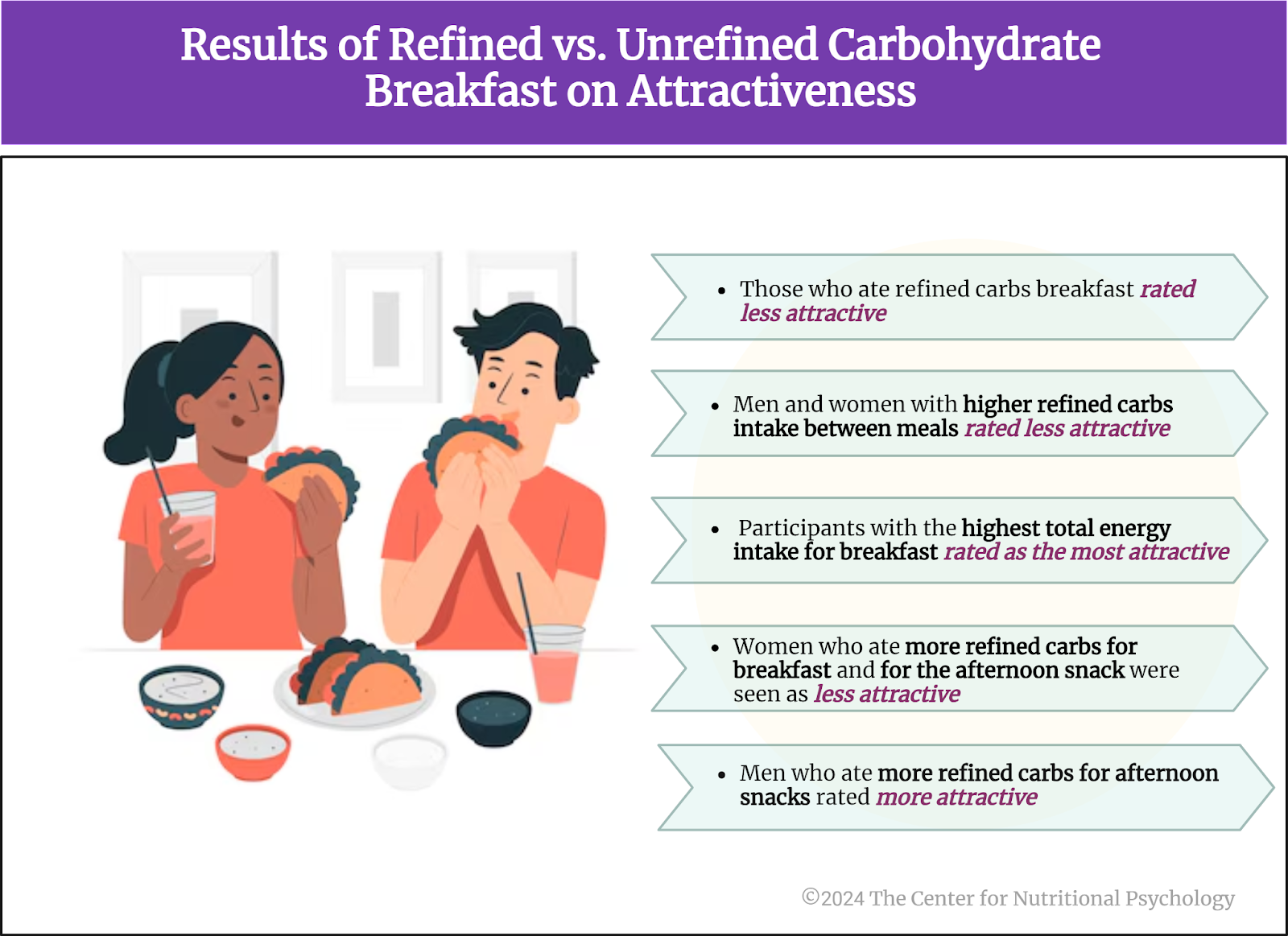

Raters rated the faces of participants who ate breakfast consisting of refined carbohydrates as less attractive than those who ate unrefined carbohydrate breakfast. Raters saw men and women from the refined carbohydrate breakfast group as less attractive.

Regarding chronic food intake, raters saw participants with the highest total energy intake for breakfast as the most attractive. They tended to rate both men and women with higher refined carbohydrate intake between meals as less attractive. Women, but not men, eating more refined carbohydrates for breakfast and for the afternoon snack were seen as less attractive. Raters saw men eating more refined carbohydrates for afternoon snacks as more attractive. Men preferred women with lower breakfast and afternoon snack glycemic load, while women preferred men with a higher afternoon snack glycemic load and a lower energy intake (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results of refined vs. unrefined carbohydrate breakfast on attractiveness

In general, higher age was associated with lower attractiveness ratings. Physical activity and perceived masculinity/femininity were associated with better attractiveness ratings.

Further analysis showed that it is possible that breakfast contents and dietary habits modified one’s age and masculine/feminine appearance. This, in turn, affected the attractiveness ratings.

Conclusion

The study shows that the immediate contents of a meal and long-term dietary habits can affect one’s attractiveness to individuals of the opposite sex. It also indicated that higher refined carbohydrate consumption reduces perceived attractiveness.

This indicates that to maintain facial beauty, one needs to consider diet, aside from other factors.

The paper “Chronic and immediate refined carbohydrate consumption and facial attractiveness” was authored by Amandine Visine, Valerie Durand, Leonard GuillouI, Michel Raymond, and Claire Berticat.

References

Borland, J., & Leigh, A. (2014). Unpacking the Beauty Premium: What Channels Does It Operate Through, and Has It Changed Over Time? Economic Record, 90(288), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12091

Dossinger, K., Wanberg, C. R., Choi, Y., & Leslie, L. M. (2019). The beauty premium: The role of organizational sponsorship in the relationship between physical attractiveness and early career salaries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.007

Little, A. C. (2021). Facial Attractiveness. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science (pp. 2887–2891). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1881

Mobius, M. M., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2006). Why Beauty Matters. American Economic Review, 96(1), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806776157515

Rhodes, G. (2006). The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208

Shavlokhova, V., Vollmer, A., Stoll, C., Vollmer, M., Lang, G. M., & Saravi, B. (2024). Assessing the Role of Facial Symmetry and Asymmetry between Partners in Predicting Relationship Duration: A Pilot Deep Learning Analysis of Celebrity Couples. Symmetry, 16(2), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym16020176

Visine, A., Durand, V., Guillou, L., Raymond, M., & Berticat, C. (2024). Chronic and immediate refined carbohydrate consumption and facial attractiveness. PLOS ONE, 19(3), e0298984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298984

Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First Impressions: Making Up Your Mind After a 100-Ms Exposure to a Face. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x

Zhan, J., Liu, M., Garrod, O. G. B., Daube, C., Ince, R. A. A., Jack, R. E., & Schyns, P. G. (2021). Modeling individual preferences reveals that face beauty is not universally perceived across cultures. Current Biology, 31(10), 2243-2252.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.013

Leave a comment