GLP-1RAs Reduce External Eating Behavior in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes

Listen to this Article

This content represents findings from one research study and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. CNP does not endorse, promote, or support the use of GLP‑1 receptor agonists or related medications for any indication. Any decisions regarding prescription medications should be made exclusively between patients and their licensed healthcare professionals.

- A multicenter observational study in Japan published in the Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare found that individuals with type 2 diabetes taking glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) showed reduced external eating scores after 12 months of therapy

- Their blood sugar levels, body weight, and body fat percentage also decreased significantly

- Emotional and restrained eating showed only transient changes.

Recent decades have seen a dramatic increase in the share of the world population suffering from overweight and obesity (Wong et al., 2022). The incidence of type 2 diabetes has also been rising throughout the world in the past decades, with this trend of increase stabilizing and even reversing in some populations only in the last 20 years (Magliano et al., 2019). This has made both diabetes and obesity key health priorities globally. As a result, many prevention programs have been implemented, but scientists have also discovered and introduced new medications for treating both conditions. One of the most potent treatments among those medications is the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

Type 2 diabetes and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic adverse health condition in which the body either resists the effects of insulin or does not produce enough to keep blood sugar at normal levels. It is primarily caused by a combination of genetic susceptibility, overweight or obesity, physical inactivity, and poor dietary habits. If left unchecked, high blood glucose levels damage blood vessels and organs over time, increasing the risk of various other serious health conditions. There is currently no effective cure, but the condition can be effectively managed through lifestyle changes, medications, and sometimes insulin therapy.

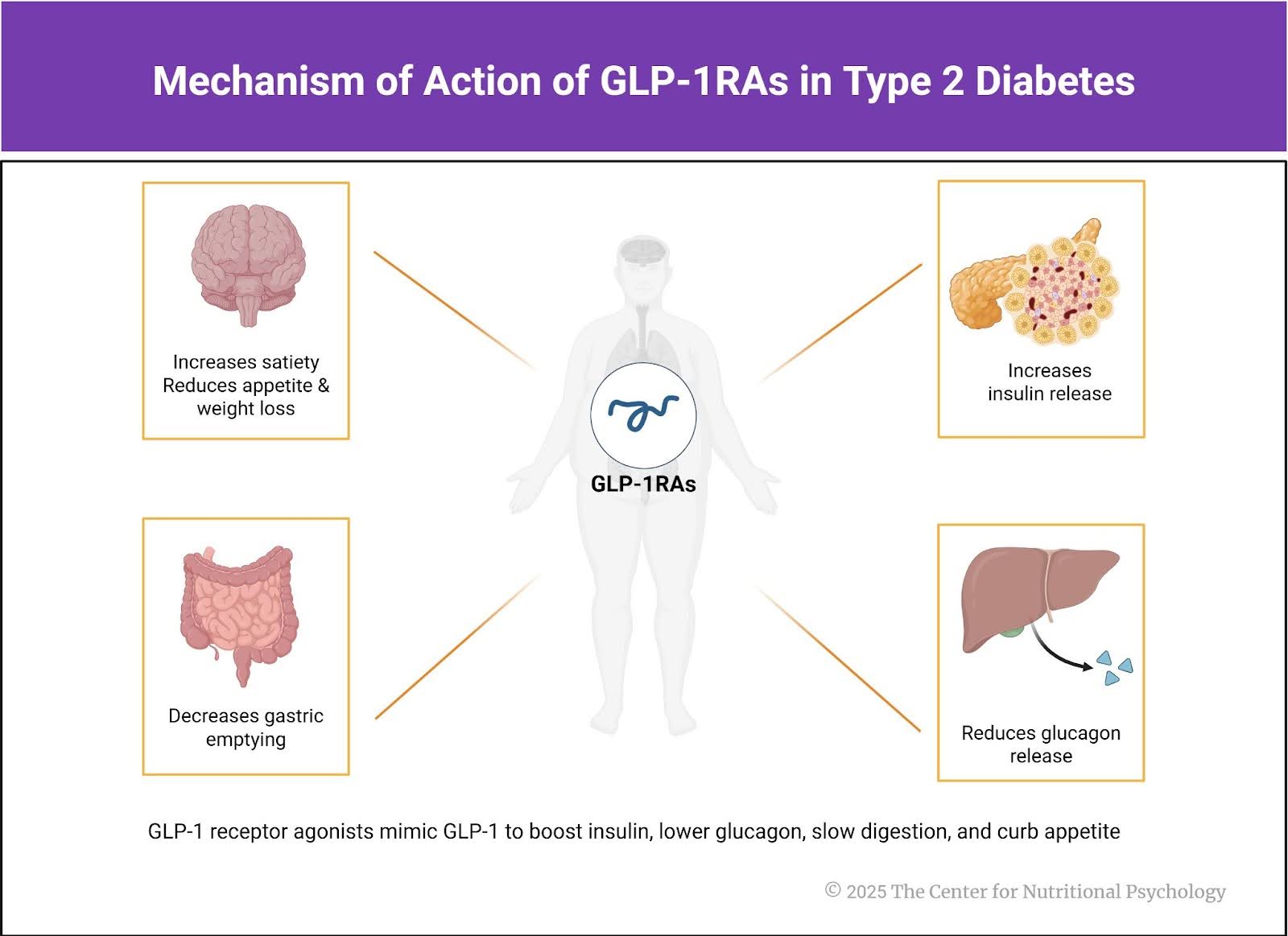

One relatively recent development in treating type 2 diabetes is the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs). First introduced in the early 2000s, these medications mimic the natural hormone glucagon-like peptide-1, which helps regulate blood sugar by stimulating insulin release and suppressing glucagon secretion after meals (glucagon is the hormone that raises blood glucose levels by stimulating the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream). GLP-1RAs also reduce food intake by modulating appetite-regulating pathways in the brain, resulting in weight loss (Koide et al., 2025) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanism of Action of GLP-1RAs in Type 2 Diabetes

These effects have positioned GLP-1RAs as a cornerstone in the management of type 2 diabetes, particularly in individuals with obesity. GLP-1RAs currently available on the market include semaglutide (sold as Ozempic and Rybelsus), liraglutide (Victoza), dulaglutide (Tulicity), exenatide (Byetta and Bydureon), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro).

Obesity

While at the most basic level, obesity is caused by a person taking in more energy than they expend over a prolonged period, it is worth noting that humans have a complex neural mechanism regulating food intake, which is generally very effective at maintaining a balance between energy intake and expenditure. However, in some individuals, the food intake control mechanism does not achieve this balance, leading to eating disorders and obesity.

Many factors contribute to dysregulation of the food intake control mechanism and, in the long term, to the development of obesity. For example, studies on rodents have long established that feeding them a diet rich in both easily digestible fats and sugars will make them obese. This is referred to as an obesogenic diet (Ikemoto et al., 1996). Studies in humans have also confirmed that consuming fat and sugar simultaneously promotes overeating (Hedrih, 2024), likely due to increased reward responses from separate neural gut-brain pathways activated by sugar and fat (McDougle et al., 2024).

Additionally, people seem to differ in their susceptibility to the rewarding effects of food. There are also many other factors influencing the risk of developing obesity, including genetics, cultural factors, the characteristics of social and physical environments one lives in, and many others (e.g., Anglé et al., 2009; Dallman et al., 2005; Gearhardt et al., 2023; Hedrih, 2024; Saelens et al., 2012).

The current study

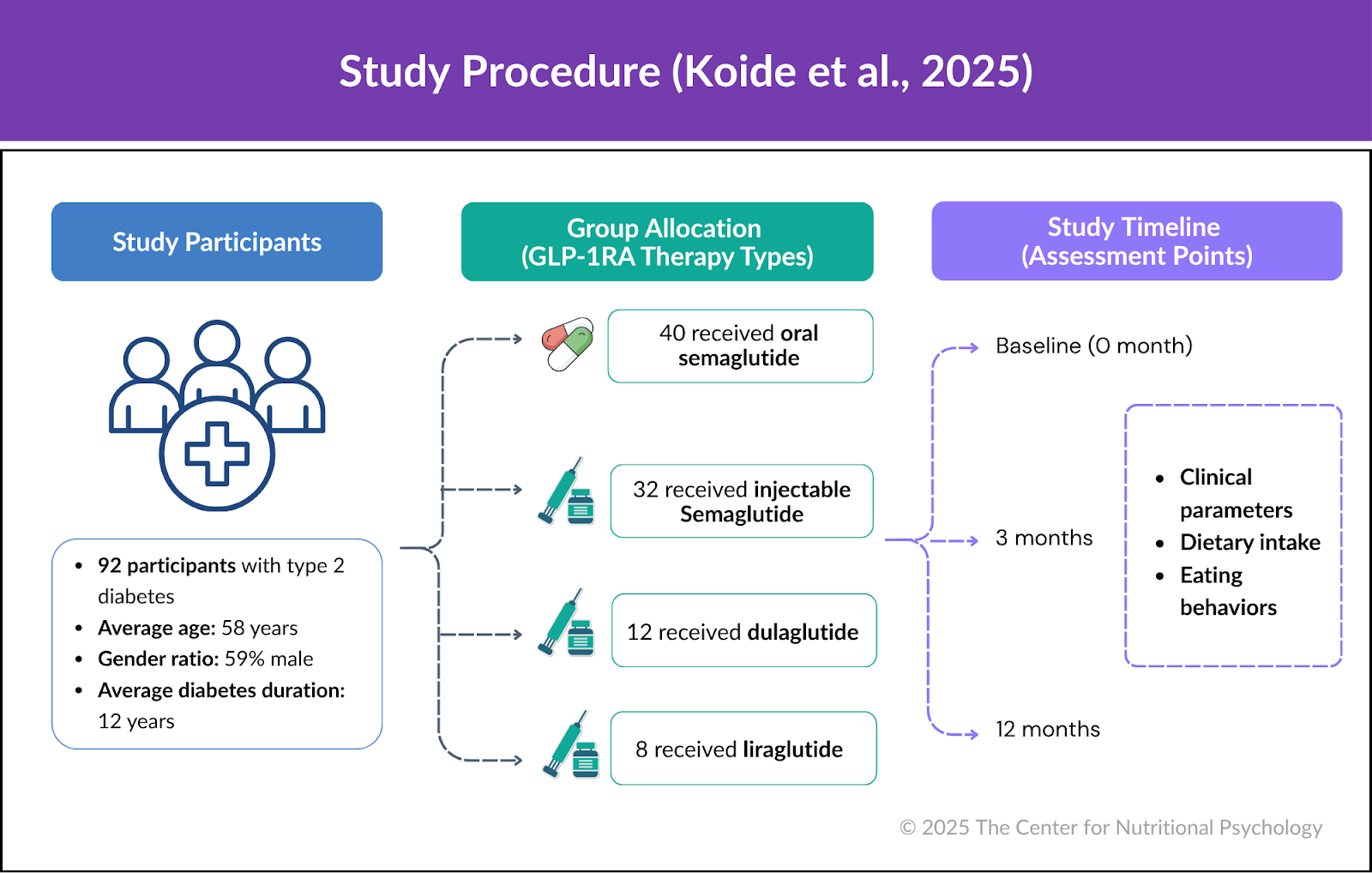

Study author Yuya Koide and his colleagues wanted to explore how individuals with type 2 diabetes respond to GLP-1RAs therapy (Koide et al., 2025). They conducted an observational study in which they enrolled 92 individuals undergoing this type of therapy at four institutions in the Gifu Prefecture, Japan. They assessed participants’ clinical parameters, dietary intake, and eating behaviors at the start of the study, 3 months after the start, and 12 months after the start.

Participants’ average age was 58 years. 59% were males. On average, they suffered from type 2 diabetes for 12 years, but this varied greatly among participants. They were treated with four different types of GLP-1RAs. Forty received oral semaglutide, 32 received injectable semaglutide, 12 received dulaglutide, while 8 received liraglutide (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Study procedure (Koide et al., 2025)

GLP-1RA therapy significantly reduced blood glucose levels, body weight, and body fat percentage

Results showed that after 12 months of treatment, GLP-1RA therapy significantly reduced participants’ blood glucose levels (as measured by glycated hemoglobin), body weight, and body fat percentage.

Participants’ external eating scores showed a sustained decrease. However, emotional and restrained eating scores exhibited only transient changes. Individuals with higher external eating scores at the start of the study tended to show greater weight loss. Restrained eating scores increased somewhat by the 3rd month, only to return to the baseline values at 12 months. The average emotional eating score decreased somewhat at month 3 but seemed to have reverted by month 12. The reduction appears to be primarily due to decreases among individuals with the highest baseline scores.

External eating is the tendency to eat in response to external cues, such as sights, smells, or the availability of food, rather than to internal feelings of hunger or fullness. Emotional eating is the tendency to eat in response to feelings such as stress, sadness, or boredom. It is a way some people use to cope with distress and negative emotions. Restrained eating is a tendency to deliberately and consciously restrict food intake to control body weight, despite feelings of hunger. The issue with restrained eating is that it requires a constant conscious effort. If the effort falters, counter-regulation may happen, leading to episodes of overeating (see Figure 1).

Conclusion

The study found that GLP-1RA therapy is effective not only in managing blood glucose levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes but also in reducing body weight in obese individuals and changing unhealthy eating tendencies, such as the tendency to eat in response to external food cues (external eating). The finding that individuals with more pronounced external eating tendencies benefited more from this treatment suggests that its potential to alter unhealthy eating patterns before adverse health conditions develop warrants further exploration.

The paper “Association between eating behavior patterns and the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a multicenter prospective observational study” was authored by Yuya Koide, Takehiro Kato, Makoto Hayashi, Hisashi Daido, Takako Maruyama, Takuma Ishihara, Kayoko Nishimura, Shin Tsunekawa, and Daisuke Yabe on behalf of G-DIET Investigators.

References

Anglé, S., Engblom, J., Eriksson, T., Kautiainen, S., Saha, M.-T., Lindfors, P., Lehtinen, M., & Rimpelä, A. (2009). Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-41

Dallman, M. F., Pecoraro, N. C., & La Fleur, S. E. (2005). Chronic stress and comfort foods: Self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 19(4), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBI.2004.11.004

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Hedrih, V. (2024, February 19). Consuming Fat and Sugar (At The Same Time) Promotes Overeating, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/16563-2/

Ikemoto, S., Takahashi, M., Tsunoda, N., Maruyama, K., Itakura, H., & Ezaki, O. (1996). High-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and obesity in mice: Differential effects of dietary oils. Metabolism, 45(12), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90185-7

Koide, Y., Kato, T., Hayashi, M., Daido, H., Maruyama, T., Ishihara, T., Nishimura, K., Tsunekawa, S., & Yabe, D. (2025). Association between eating behavior patterns and the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A multicenter prospective observational study. Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare, 6, 1638681. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcdhc.2025.1638681

Magliano, D. J., Islam, R. M., Barr, E. L. M., Gregg, E. W., Pavkov, M. E., Harding, J. L., Tabesh, M., Koye, D. N., & Shaw, J. E. (2019). Trends in incidence of total or type 2 diabetes: Systematic review. BMJ, 366, l5003. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5003

McDougle, M., de Araujo, A., Singh, A., Yang, M., Braga, I., Paille, V., Mendez-Hernandez, R., Vergara, M., Woodie, L. N., Gour, A., Sharma, A., Urs, N., Warren, B., & de Lartigue, G. (2024). Separate gut-brain circuits for fat and sugar reinforcement combine to promote overeating. Cell Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.014

Saelens, B. E., Sallis, J. F., Frank, L. D., Couch, S. C., Zhou, C., Colburn, T., Cain, K. L., Chapman, J., & Glanz, K. (2012). Obesogenic Neighborhood Environments, Child and Parent Obesity: The Neighborhood Impact on Kids Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(5), e57–e64. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2012.02.008

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005

Navigation

Navigation

Leave a comment