Study Finds Added Sugar Linked to Poor Sleep in Young People

Listen to this Article

- A survey of Saudi Arabian female students published in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine examined the links between eating habits and sleep quality

- Results showed that students consuming higher quantities of foods with added sugars tended to have worse sleep quality

- Study authors report that only 17% of study participants had good sleep quality

We all know that many factors can prevent us from sleeping well. Worrying about something can keep us awake for a long time. Similarly, when we are doing something exciting, we may forget to get enough sleep. However, if we chronically lack sufficient sleep, it will become increasingly difficult to function properly until we have had proper rest.

The importance of sleep

Sleep is a natural state of rest in which the body and mind become less responsive to external stimuli and engage in essential recovery processes. It plays a vital role in physical health, emotional well-being, and cognitive functioning, such as memory consolidation and learning. During sleep, the body repairs tissues, balances hormones, and strengthens the immune system.

However, many people experience sleep problems. This includes young people and adolescents. Estimates state that the prevalence of insomnia, one of the most common sleep disturbances, is comparable to that of depression and anxiety (Roberts et al., 2008).

The prevalence of insomnia, one of the most common sleep disturbances, is comparable to that of depression and anxiety

Sleep can also be nonrestorative. This is a situation where a person sleeps but does not feel refreshed and rested afterward (Stone et al., 2008). Many individuals experience insufficient sleep, poor sleep quality, or trouble falling asleep (Wang et al., 2023). While acute lack of sleep can be compensated by longer sleep later, studies clearly link chronic poor sleep quality or insufficient sleep with serious adverse health outcomes, such as type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease (Sofi et al., 2014; Vgontzas et al., 2009).

Sleep, diet, and eating disorders

Studies also link poor sleep quality with changes in food-related behaviors. For example, insufficient sleep is one of the key determinants of excess body weight (Bacaro et al., 2020; Cappuccio et al., 2008). More specifically, eating during the night, i.e., the time when one should be sleeping, is an important predictor of weight gain. A 2008 study found that individuals who eat at night consume 15% of their daily calories during nighttime eating episodes. In this study, they gained several kilograms more weight during the study period compared to participants who did not eat at night (Gluck et al., 2008).

Insufficient sleep is one of the key determinants of excess body weight

When night eating is accompanied by increased food intake in the evening, avoidance of eating in the morning, a declining mood that worsens in the evening, and emotional distress, it becomes a type of eating disorder called night eating syndrome (Tzischinsky et al., 2021).

Studies also indicate that people increase their food intake when they are acutely deprived of sleep, even in the absence of chronic sleep problems (Brondel et al., 2010). Researchers have found that individuals with shorter sleep durations consume fewer fruits and vegetables, while those suffering from chronic insomnia tend to eat more ultraprocessed foods (Duquenne et al., 2024; Thapa et al., 2024).

People increase their food intake when they are acutely deprived of sleep, even in the absence of chronic sleep problems

The current study

Study author Sarah A. Alahmary and her colleagues sought to investigate the relationship between the consumption of foods high in added sugars and sleep quality among female university students at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University in Dammam, Saudi Arabia (Alahmary et al., 2022). They note that previous studies have shown that consuming high amounts of added sugar increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and even some forms of cancer. But what about sleep?

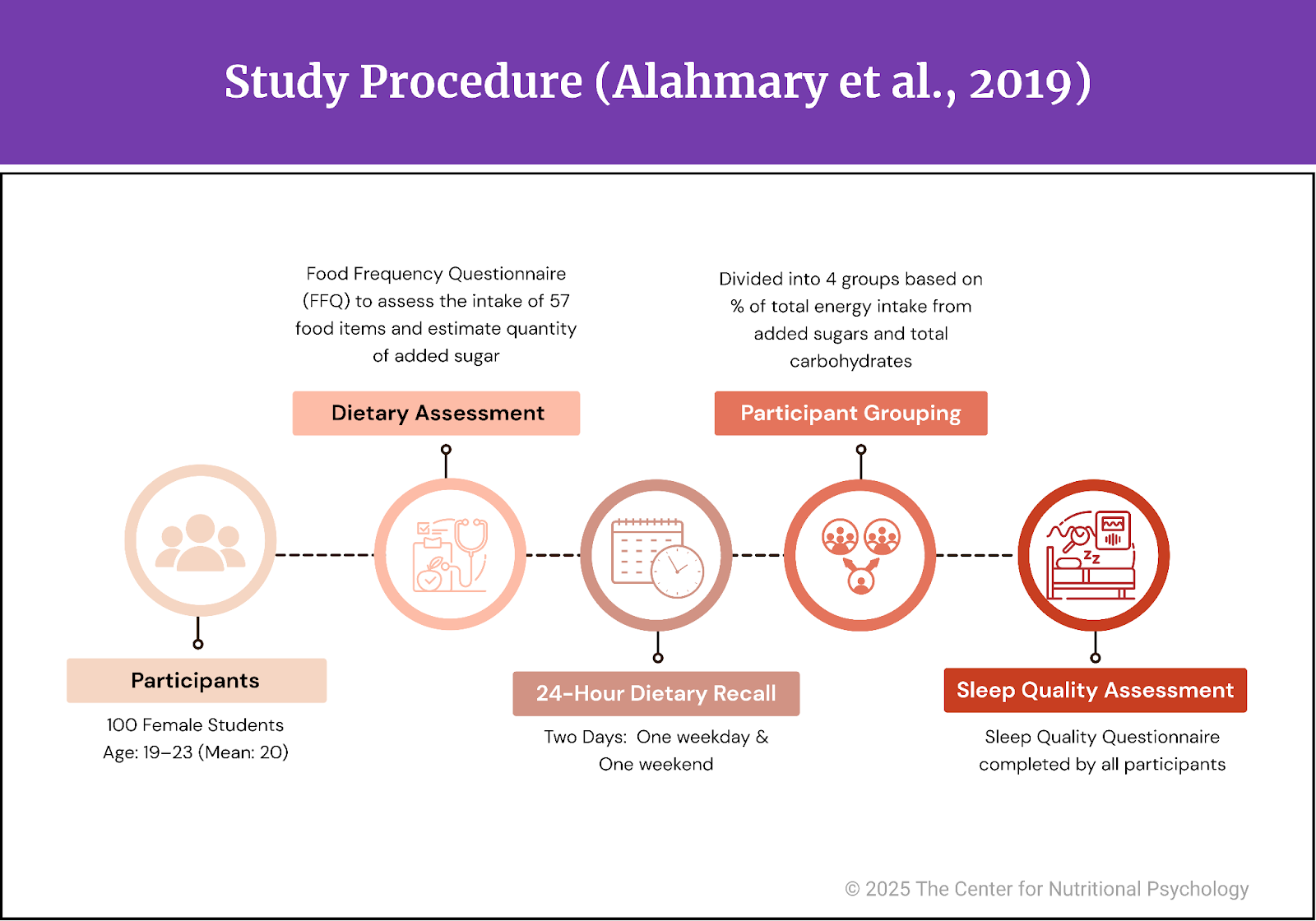

The study participants were 100 female students from the College of Applied Studies and Community Service at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. They were between 19 and 23 years of age, with the mean age being 20 years.

The students completed a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), which asked them about their consumption of 57 different types of food. For each of these items, the study authors estimated the quantity of added sugar. Participants also completed a 24-hour dietary recall for two different days – one weekday and one weekend day. Based on this, the study authors divided participants into four groups according to the contribution of added sugars and total carbohydrates to their total daily energy intake. Participants also completed the Sleep Quality Questionnaire (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Procedure (Alahmary et al., 2019)

Higher intake of added sugar was associated with worse sleep quality

Results showed that only 17% of students reported good sleep quality. This means that they slept from 7 to 8.5 hours continuously at night, needed less than 15 minutes to fall asleep, did not use any sleeping pills, and were not suffering from insomnia.

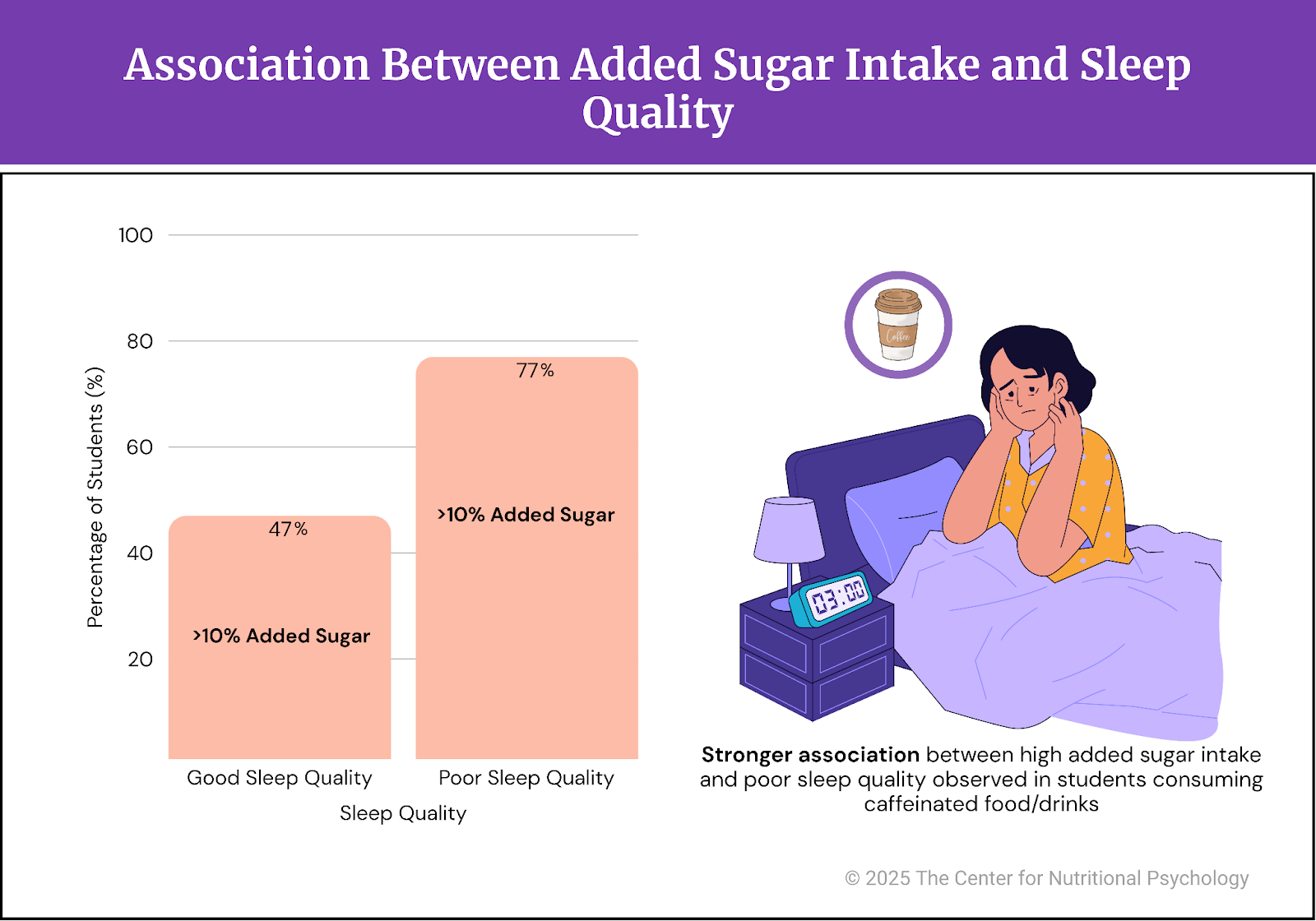

Higher intake of added sugar (as estimated through 24-hour dietary recall) was associated with poorer sleep quality. Seventy-seven percent of students in the poor sleep quality group had more than 10% of added sugar in their diet, whereas this was the case with only 47% of students who had good sleep quality. Further analysis revealed that this association was stronger among students who were consuming food items containing caffeine.

On the other hand, the link between added sugar intake and sleep quality was not so clear when added sugar intake was estimated using the Food Frequency Questionnaire (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Association of added sugar intake and sleep quality

Conclusion

The study shows that a higher intake of added sugars was associated with poorer sleep quality. Although the design of this study does not allow for causal inferences to be drawn from these results, the findings suggest that limiting added sugar intake may help improve sleep quality. Given the existing findings on the links between added sugar intake and other adverse health outcomes, reducing added sugar intake may have a broader beneficial effect on overall health as well.

The paper “Relationship Between Added Sugar Intake and Sleep Quality Among University Students: A Cross-sectional Study” was authored by Sarah A. Alahmary, Sakinah A. Alduhaylib, Hibah A. Alkawii, Mashail M. Olwani, Reem A. Shablan, Hala M. Ayoub, Tunny S. Purayidathil, Omar I. Abuzaid, and Rabie Y. Khattab.

References

Alahmary, S. A., Alduhaylib, S. A., Alkawii, H. A., Olwani, M. M., Shablan, R. A., Ayoub, H. M., Purayidathil, T. S., Abuzaid, O. I., & Khattab, R. Y. (2022). Relationship Between Added Sugar Intake and Sleep Quality Among University Students: A Cross-sectional Study. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 16(1), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827619870476

Bacaro, V., Ballesio, A., Cerolini, S., Vacca, M., Poggiogalle, E., Donini, L. M., Lucidi, F., & Lombardo, C. (2020). Sleep duration and obesity in adulthood: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 14(4), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2020.03.004

Brondel, L., Romer, M. A., Nougues, P. M., Touyarou, P., & Davenne, D. (2010). Acute partial sleep deprivation increases food intake in healthy men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(6), 1550–1559. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28523

Cappuccio, F. P., Taggart, F. M., Kandala, N.-B., Currie, A., ChB, M., Peile, E., & Miller, M. A. (2008). Meta-Analysis of Short Sleep Duration and Obesity in Children and Adults. 31(5).

Duquenne, P., Capperella, J., Fezeu, L. K., Srour, B., Benasi, G., Hercberg, S., Touvier, M., Andreeva, V. A., & St-Onge, M.-P. (2024). The association between ultra-processed food consumption and chronic insomnia in the NutriNet-Santé Study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, S2212267224000947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2024.02.015

Gluck, M. E., Venti, C. A., Salbe, A. D., & Krakoff, J. (2008). Nighttime eating: Commonly observed and related to weight gain in an inpatient food intake study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 88(4), 900–905. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/88.4.900

Roberts, R. E., Roberts, C. R., & Duong, H. T. (2008). Chronic Insomnia and Its Negative Consequences for Health and Functioning of Adolescents: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.016

Sofi, F., Cesari, F., Casini, A., Macchi, C., Abbate, R., & Gensini, G. (2014). Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 21, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487312460020

Stone, K. C., Taylor, D. J., McCrae, C. S., Kalsekar, A., & Lichstein, K. L. (2008). Nonrestorative sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 12(4), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.12.002

Thapa, A., Lahti, T., Maukonen, M., & Partonen, T. (2024). Consumption of fruits and vegetables and its association with sleep duration among Finnish adult population: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1319821. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1319821

Tzischinsky, O., Latzer, I. T., Alon, S., & Latzer, Y. (2021). Sleep quality and eating disorder-related psychopathologies in patients with night eating syndrome and binge eating disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194613

Vgontzas, A. N., Liao, D., Pejovic, S., Calhoun, S., Karataraki, M., & Bixler, E. O. (2009). Insomnia With Objective Short Sleep Duration Is Associated With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 32(11), 1980–1985. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-0284

Wang, S., Rossheim, M. E., & Nandy, R. R. (2023). Trends in prevalence of short sleep duration and trouble sleeping among US adults, 2005–2018. Sleep, 46(1), zsac231. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsac231

Navigation

Navigation

Leave a comment