Women Who Eat Healthier and Reduce Sugar Intake Age More Slowly

Listen to this Article

- A study published in JAMA Network Open examined associations among epigenetic age, added sugar intake, and several indices of dietary health in a group of women.

- Participants who ate healthier tended to have lower epigenetic age, i.e., their cells seemed to age more slowly

- Participants who reported higher added-sugar intake tended to age slightly faster.

It is sometimes difficult to tell how old a person is from the way they look. Some people look younger than one would expect based on their calendar age. Other people look older. We also know that this can be influenced by life events. “He aged overnight” or “The stress took years off her life” are common sayings used to describe situations where people suddenly start looking or feeling much older because of the extreme stress, grief, or hardship they went through. However, this perception that some people show accelerated aging, while others seem to stay younger longer, is not only subjective. Science has long used indicators of age based on the condition of the body rather than on calendar age (Jackson et al., 2003; Jylhävä et al., 2017).

Chronological Age vs Biological Age

If we simply measure the time since a person was born, we obtain that person’s calendar or chronological age. Calendar age is useful for various legal purposes and for recording and interpreting life events. However, scientists noticed relatively early that it often does not adequately reflect a person’s level of development or the age-related condition of their body.

Why Calendar Age Does Not Reflect True Aging

For example, when intelligence testing of children began to develop in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, psychologists of the time quickly introduced the concept of mental age, noting the unequal pace of children’s intellectual development (Hedrih, 2020). The idea was later abandoned (after they realized that individual differences in cognitive abilities do not boil down to different paces of development). Still, it clearly shows that calendar age and the body’s age often do not match.

What Is Biological Age?

To account for differences in the pace of aging and how aged a body appears, scientists developed the concept of biological age. Biological age is a measure of how old one’s body appears to be based on its physiological and cellular conditions. Interestingly, many authors who write about biological age and its indicators do not explicitly define what biological age is (e.g., Jackson et al., 2003; Jylhävä et al., 2017). Those who do often do that in different ways.

Biological age. Biological age is a measure of how old one’s body appears to be based on its physiological and cellular conditions.

For example, Demongeot (2009) views biological age as the stage of development and aging of an organ or organism, determined by the number of cell divisions already undergone and those remaining before reaching the Hayflick limit. The Hayflick limit is the maximum number of times a normal human cell can divide (typically around 50 times) before it stops replicating and enters a state of senescence. Other indicators of biological age have also been proposed through history, starting from the strength of spectacles one needs to read (due to age-related presbyopia, i.e., gradual decrease of the elasticity of the eye lens), health status, frailty, DNA methylation to various other genetic markers (Demongeot, 2009; Jackson et al., 2003; Jylhävä et al., 2017).

Epigenetic Age and DNA Methylation Explained

One of the powerful indicators of biological age is a change in gene and protein expression patterns, particularly those driven by differential DNA methylation. As people age, small chemical units called methyl groups (-CH3) get added to cytosine bases in DNA, altering gene expression without changing the genetic code. This typically happens at places on DNA where a cytosine nucleotide is directly followed by a guanine nucleotide, called CpG sites.

These methyl groups on the DNA tend to accumulate over time, indicating the age of the DNA strand. Scientists use data on DNA methylation across the genome to create mathematical models, called epigenetic clocks, that estimate a type of biological age called epigenetic age.

The current study : Diet Quality and Epigenetic Aging in Midlife Women

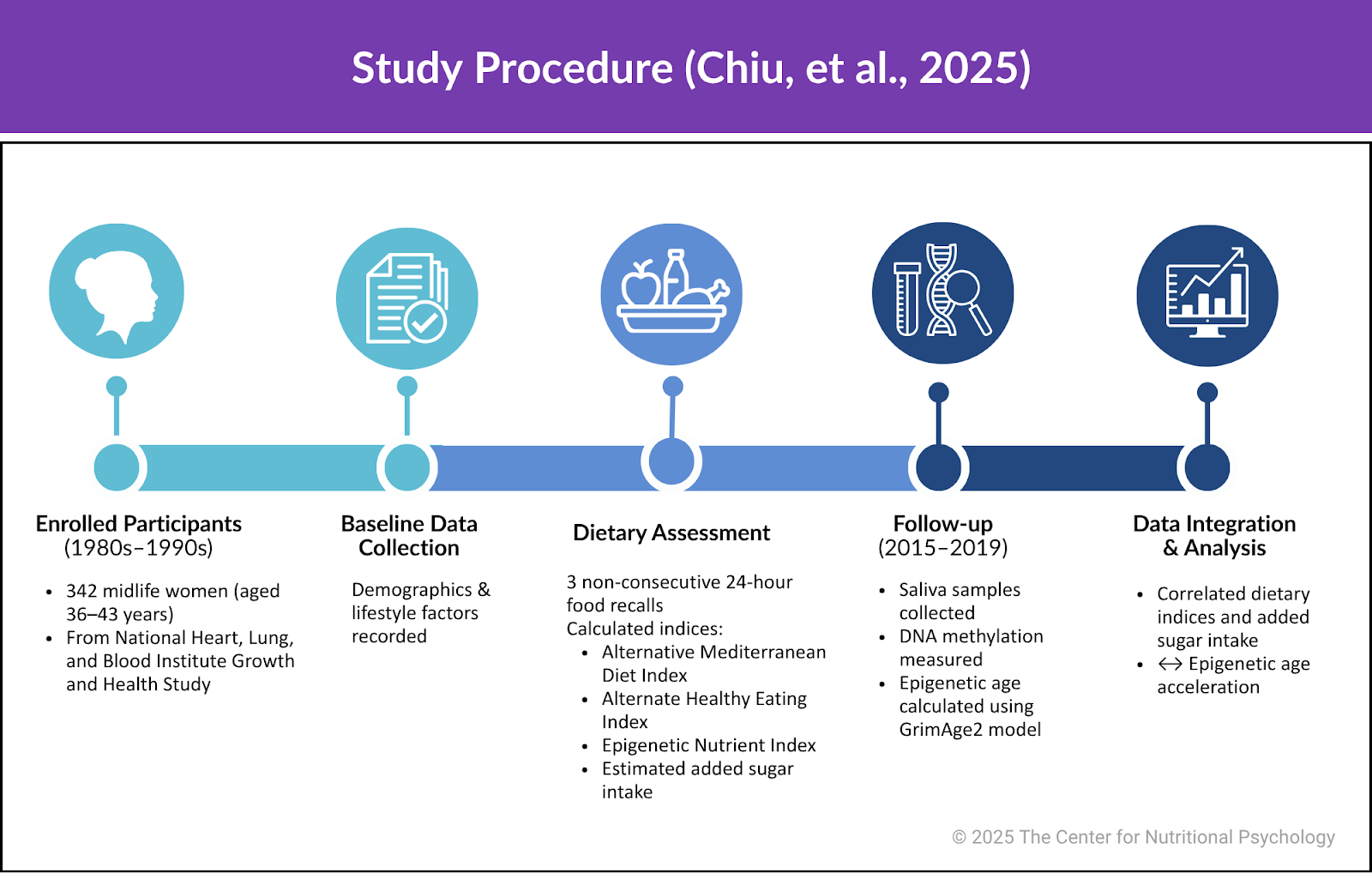

Study author Dorothy T. Chiu and her colleagues sought to investigate the association between dietary patterns—including intakes of essential nutrients and added sugar—and epigenetic age in midlife women (Chiu et al., 2024). They analyzed data from 342 women who participated in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health study in the 1980s and 1990s and also participated in its follow-up (2015-2019).

These women were 36-43 years old when they enrolled in the study. They provided demographic information, reported their food intake for three non-consecutive days, and gave saliva samples. The saliva samples allowed researchers to analyze DNA methylation and calculate epigenetic age using the GrimAge2 epigenetic clock model. From participants’ food intake data, the study authors calculated several dietary pattern indices, including the Alternative Mediterranean Diet Index, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and the Epigenetic Nutrient Index, and estimated added sugar intake (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study procedure (Chiu, et al., 2025)

Healthier eating was associated with slower aging

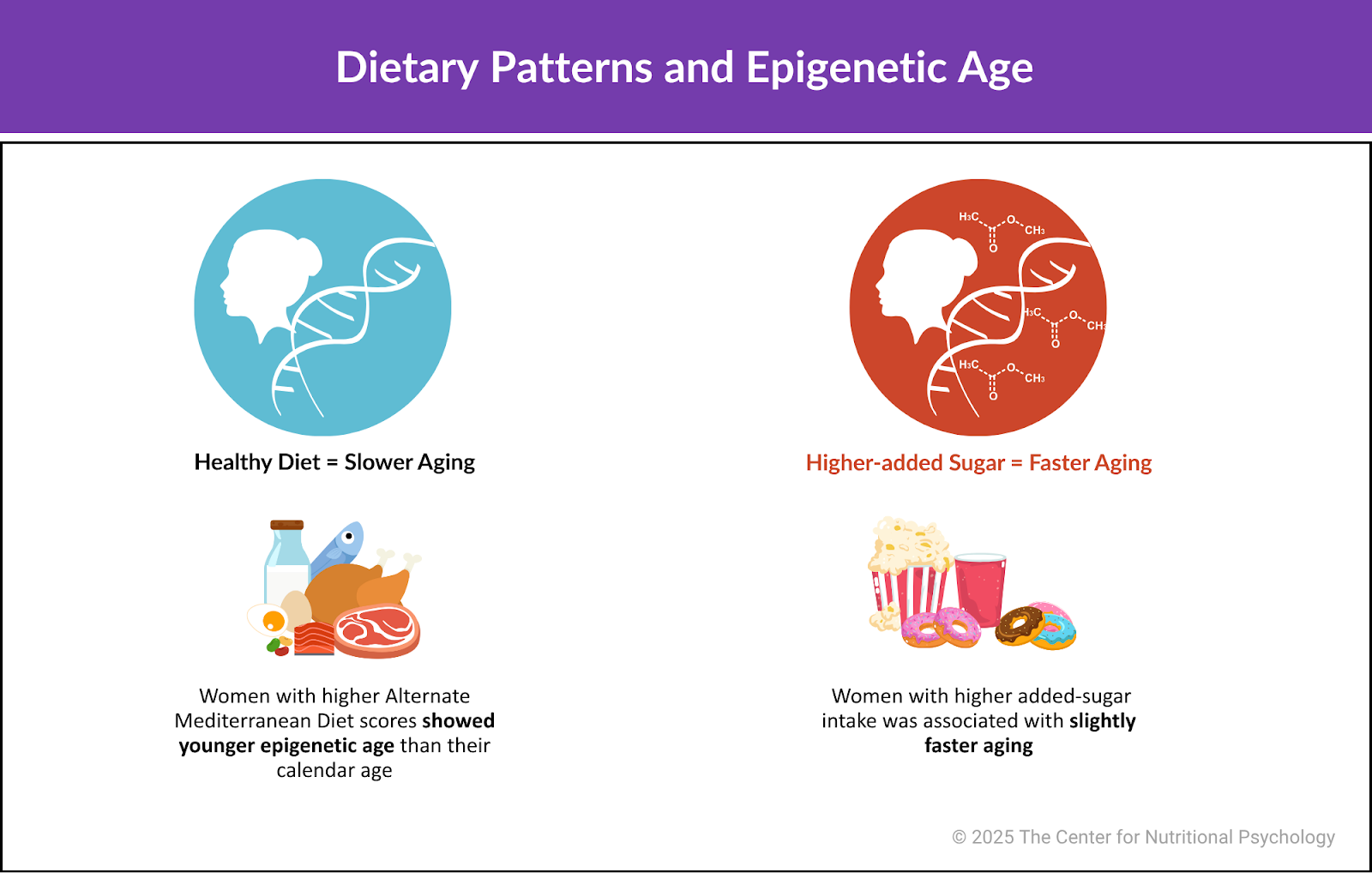

Results showed that participants who ate healthier tended to have epigenetic age that was lower than their calendar age. In other words, they aged more slowly. The strongest association between epigenetic age and dietary pattern score was with the alternate Mediterranean diet, while associations with other dietary pattern indices were weaker, but all in expected directions.

The Alternate Mediterranean Diet is a healthy dietary pattern adapted from the traditional Mediterranean diet, emphasizing fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fish, and healthy fats, while limiting red meat and processed foods.

Additionally, individuals with higher added-sugar intake tended to show accelerated aging. However, this association was very weak (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dietary pattern and epigenetic age

Conclusion

The study showed that adherence to healthy dietary patterns, and particularly to the Alternate Mediterranean Diet, is associated with slower biological (epigenetic) aging. Higher added sugar intake was associated with slightly faster aging.

While the design of this study does not allow any definitive causal inferences to be derived from the results, it is possible that healthier dietary patterns and reduced added sugar intake could support slower aging and potentially contribute to the prevention of various chronic diseases.

The paper “Essential Nutrients, Added Sugar Intake, and Epigenetic Age in Midlife Black and White Women NIMHD Social Epigenomics Program” was authored by Dorothy T. Chiu, Elissa June Hamlat, Joshua Zhang, Elissa S. Epel, and Barbara A. Laraia.

References

Chiu, D. T., Hamlat, E. J., Zhang, J., Epel, E. S., & Laraia, B. A. (2024). Essential Nutrients, Added Sugar Intake, and Epigenetic Age in Midlife Black and White Women: NIMHD Social Epigenomics Program. JAMA Network Open, 7(7), e2422749. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22749

Demongeot, J. (2009). Biological Boundaries and Biological Age. Acta Biotheoretica, 57(4), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10441-009-9087-8

Hedrih, V. (2020). Adapting Psychological Tests and Measurement Instruments for Cross-Cultural Research: An Introduction (1st Edition). Routledge, Taylor&Francis Group.

Jackson, S. H. D., Weale, M. R., & Weale, R. A. (2003). Biological age—What is it and can it be measured? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 36(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4943(02)00060-2

Jylhävä, J., Pedersen, N. L., & Hägg, S. (2017). Biological Age Predictors. eBioMedicine, 21, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.046

Navigation

Navigation

Leave a comment