People Consuming Lots of Ultra-Processed Foods Tend to Have Slightly Worse Mental Health Indicators

Listen to this Article

- The results of a survey of Turkish adults published in Food Science & Nutrition showed that individuals consuming more ultraprocessed food tended to self-report slightly more severe symptoms of food addiction.

- These individuals also tended to report slightly greater symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.

- Younger participants, women, those unemployed, and single individuals tended to consume more ultraprocessed foods.

We all know that consuming nutritious meals made from healthy ingredients is beneficial for our health. However, we have all been in situations where we don’t have the time or energy to invest in preparing such a meal, but we opt for something readily available instead. There are likely also times when we are drawn by the taste or smell of some industrially prepared food item, and times when such meals were the only available option.

While such ready-made foods were relatively rare in earlier times, studies indicate that the consumption of industrially processed foods has been increasing rapidly in recent decades. This is particularly true for ultra-processed foods (Baker et al., 2020; Juul et al., 2022; Juul & Hemmingsson, 2015).

The consumption of industrially processed foods has increased rapidly in recent decades.

Ultraprocessed foods

Ultra-processed foods are industrially manufactured food products that contain ingredients not typically used in home cooking. These include artificial flavors, preservatives, emulsifiers, and colorings. They are typically made from industrial formulations of substances extracted from foods (like oils, sugars, starches, and proteins) with little to no intact whole food content. Ultra-processed foods are designed to be convenient, palatable, and long-lasting (Hedrih, 2024; Monteiro et al., 2019).

Common examples include sugary cereals, instant noodles, soft drinks, packaged snacks, and ready-to-eat meals. Unlike minimally processed foods, ultra-processed products tend to be low in essential nutrients and high in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats.

Ultraprocessed foods and health

More and more studies link regular consumption of ultra-processed food to adverse health outcomes such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes, depression, and even sleep problems (Duquenne et al., 2024; Hedrih, 2024a; Lane et al., 2024). Studies suggest that long-term consumption of foods rich in easily digestible fats and sugars can dysregulate the brain’s mechanisms for regulating food intake. This mechanism makes us feel satiated and prevents us from eating when we have eaten enough, thereby reducing the risk of obesity. This phenomenon is well-known from studies on rodents, where such diets are referred to as obesogenic diets because they are used to induce obesity in these animals (Ikemoto et al., 1996).

Ultra-processed foods are most often made to be rich in easily digestible fats and sugars, a combination that is rare in natural foods. Even when whole foods contain both fats and sugars in high quantities, such as in almonds, these nutrients are embedded in a fibrous matrix that slows digestion and absorption. Given that the central nervous system has separate neural pathways that react to fats and sugars and link into regions of the brain involved in reward processing, the consumption of ultra-processed foods triggers activity in both of these pathways, resulting in feelings of pleasure rarely experienced from eating natural foods (McDougle et al., 2024; Hedrih, 2024b).

Whole foods have nutrients embedded in a fibrous matrix that slows digestion and absorption.

There are also indications that some ultra-processed foods contain additives that can trigger reactions in the brain similar to those seen in various addictions. All of this makes some authors talk about food addiction and link ultra-processed foods to the development of this condition (Gearhardt et al., 2023; Hedrih, 2023).

Some ultra-processed foods contain additives that can trigger reactions in the brain similar to those seen in various addictions.

The current study

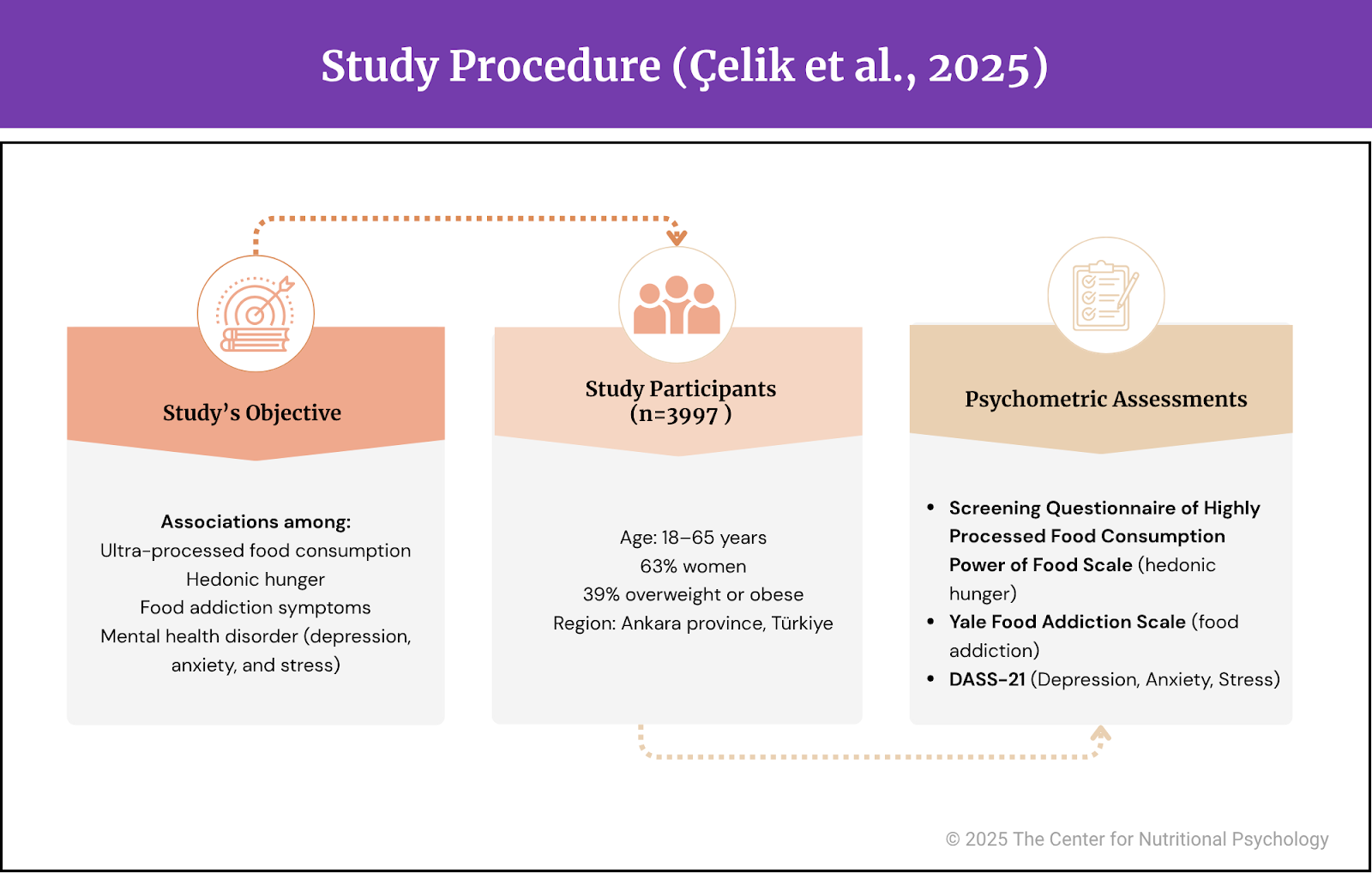

Study author Özge Mengi Çelik and her colleagues wanted to examine the associations between ultra-processed food consumption, hedonic hunger, food addiction symptoms, and mental health indicators (depression, anxiety, and stress). They conducted an online survey.

Study participants were 3,997 individuals between 18 and 65 years of age from Ankara Province, Türkiye. 63% of them were women. 39% were overweight or obese.

The survey contained assessments of ultra-processed food consumption (the Screening Questionnaire of Highly Processed Food Consumption), hedonic hunger (the Power of Food Scale), food addiction (the Yale Food Addiction Scale), and mental health symptoms (the DASS-21 scale). Participants also reported their body weight and height (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study procedure (Çelik et al., 2025)

Hedonic hunger refers to a strong desire or preoccupation with consuming food for the enjoyment and pleasure it brings rather than responding to actual physical hunger cues. It involves craving food based on the pleasurable eating experience rather than fulfilling a genuine nutritional need. Food addiction refers to a condition where individuals exhibit compulsive behaviors, cravings, and loss of control around food consumption, similar to patterns observed in substance addiction (Encyclopedia of Nutritional Psychology, 2025).

Individuals consuming lots of ultra-processed foods were more prone to hedonic hunger

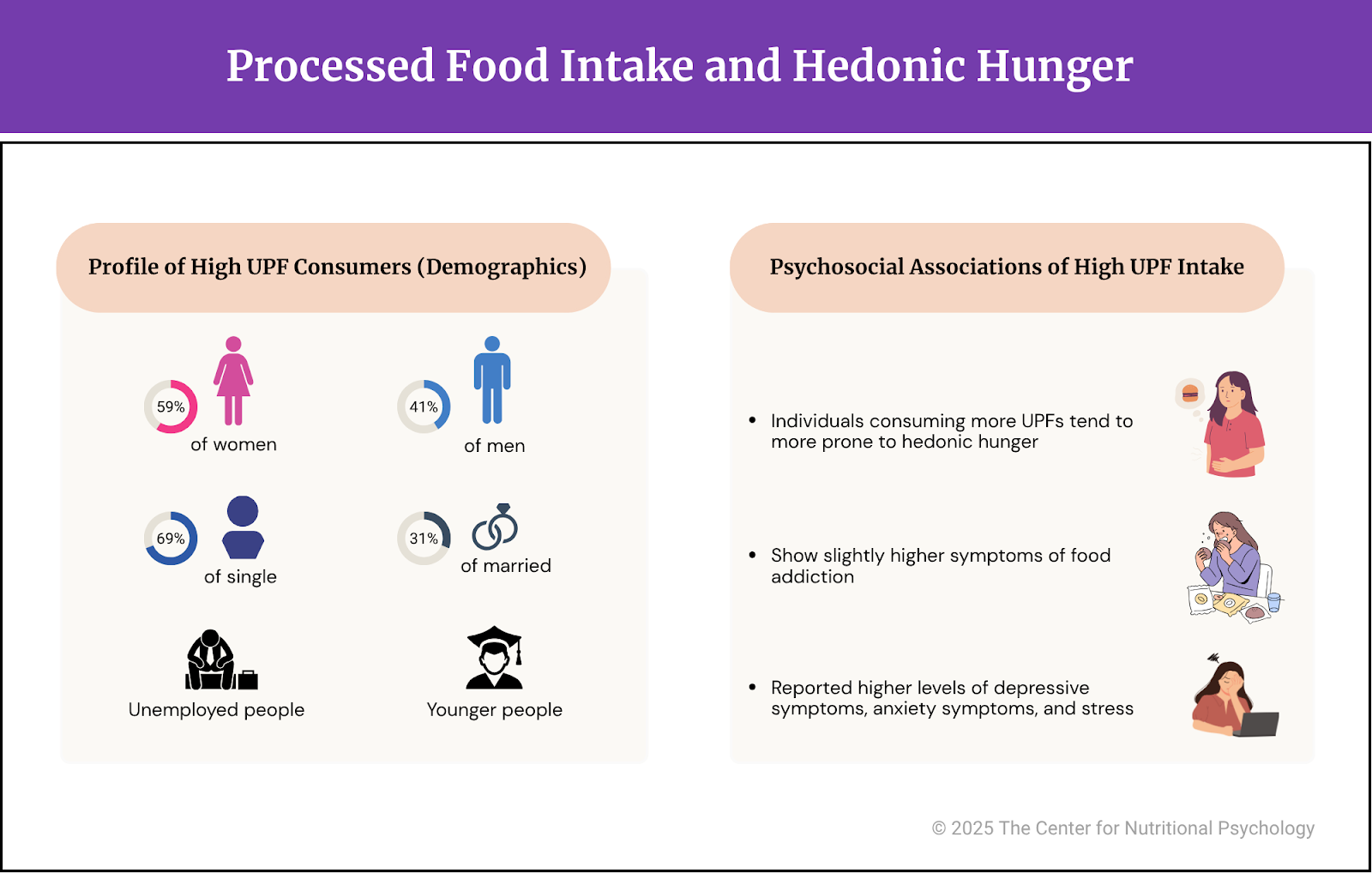

Results showed that individuals reporting higher consumption of ultra-processed foods tended to be more prone to hedonic hunger. They also tended to show somewhat higher symptoms of food addiction. Similarly, these individuals tended to report higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and stress.

Individuals with higher levels of ultra-processed food consumption tended to be younger and were more likely to be women. Overall, 59% of women and 41% of men were classified as high consumers of ultra-processed foods. Individuals in the high ultra-processed food consumption category were also more likely to be single than married (69% vs. 31%) and were more likely to be unemployed. Ultra-processed food consumption was not associated with the number of meals or snacks consumed in a typical day (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Processed food intake and hedonic hunger

Conclusion

Overall, the study results confirm a link between the consumption of ultra-processed foods and mental health. Individuals with high quantities of ultra-processed food in their diet tended to report experiencing hedonic hunger somewhat more often and having somewhat worse mental health symptoms.

While the study’s design does not allow for causal inferences to be drawn from the results, it does support the notion that promoting healthy eating habits can be a relatively simple way to support overall physical and mental health.

The paper “Factors Affecting Ultra-Processed Food Consumption: Hedonic Hunger, Food Addiction, and Mood” was authored by Özge Mengi Çelik, Ümmügülsüm Güler, and Emine Merve Ekici.

References

Baker, P., Machado, P., Santos, T., Sievert, K., Backholer, K., Hadjikakou, M., Russell, C., Huse, O., Bell, C., Scrinis, G., Worsley, A., Friel, S., & Lawrence, M. (2020). Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obesity Reviews, 21(12), e13126. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13126

Duquenne, P., Capperella, J., Fezeu, L. K., Srour, B., Benasi, G., Hercberg, S., Touvier, M., Andreeva, V. A., & St-Onge, M.-P. (2024). The association between ultra-processed food consumption and chronic insomnia in the NutriNet-Santé Study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, S2212267224000947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2024.02.015

Encyclopedia of Nutritional Psychology. (2025). The Center for Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/encyclopedia/

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Hedrih, V. (2023). Scientists Propose that Ultra-Processed Foods be Classified as Addictive Substances. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/scientists-propose-that-ultra-processed-foods-be-classified-as-addictive-substances/

Hedrih, V. (2024a). What are Ultra-Processed Foods Doing to Your Mental and Physical Health? CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/what-are-ultra-processed-foods-doing-to-your-mental-and-physical-health/

Hedrih, V. (2024b). Consuming Fat and Sugar (At The Same Time) Promotes Overeating, Study Finds. CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/16563-2/

Ikemoto, S., Takahashi, M., Tsunoda, N., Maruyama, K., Itakura, H., & Ezaki, O. (1996). High-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and obesity in mice: Differential effects of dietary oils. Metabolism, 45(12), 1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90185-7

Juul, F., & Hemmingsson, E. (2015). Trends in consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Sweden between 1960 and 2010. Public Health Nutrition, 18(17), 3096–3107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015000506

Juul, F., Parekh, N., Martinez-Steele, E., Monteiro, C. A., & Chang, V. W. (2022). Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(1), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab305

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., Ashtree, D. N., McGuinness, A. J., Gauci, S., Baker, P., Lawrence, M., Rebholz, C. M., Srour, B., Touvier, M., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Segasby, T., & Marx, W. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

McDougle, M., de Araujo, A., Singh, A., Yang, M., Braga, I., Paille, V., Mendez-Hernandez, R., Vergara, M., Woodie, L. N., Gour, A., Sharma, A., Urs, N., Warren, B., & de Lartigue, G. (2024). Separate gut-brain circuits for fat and sugar reinforcement combine to promote overeating. Cell Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.014

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Levy, R. B., Moubarac, J. C., Louzada, M. L. C., Rauber, F., Khandpur, N., Cediel, G., Neri, D., Martinez-Steele, E., Baraldi, L. G., & Jaime, P. C. (2019). Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

Navigation

Navigation

Leave a comment