The Center for Nutritional Psychology Summary of USDA and HHS Published Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030

Listen to this Article

Editor’s Note: This CNP summary presents the newly released Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025–2030, exactly as published, without additional commentary. The CNP team is currently conducting an internal review to assess these guidelines and their implications for nutritional psychology.

Overview of the USDA & HHS Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2025–2030)

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published new Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2025-2030).

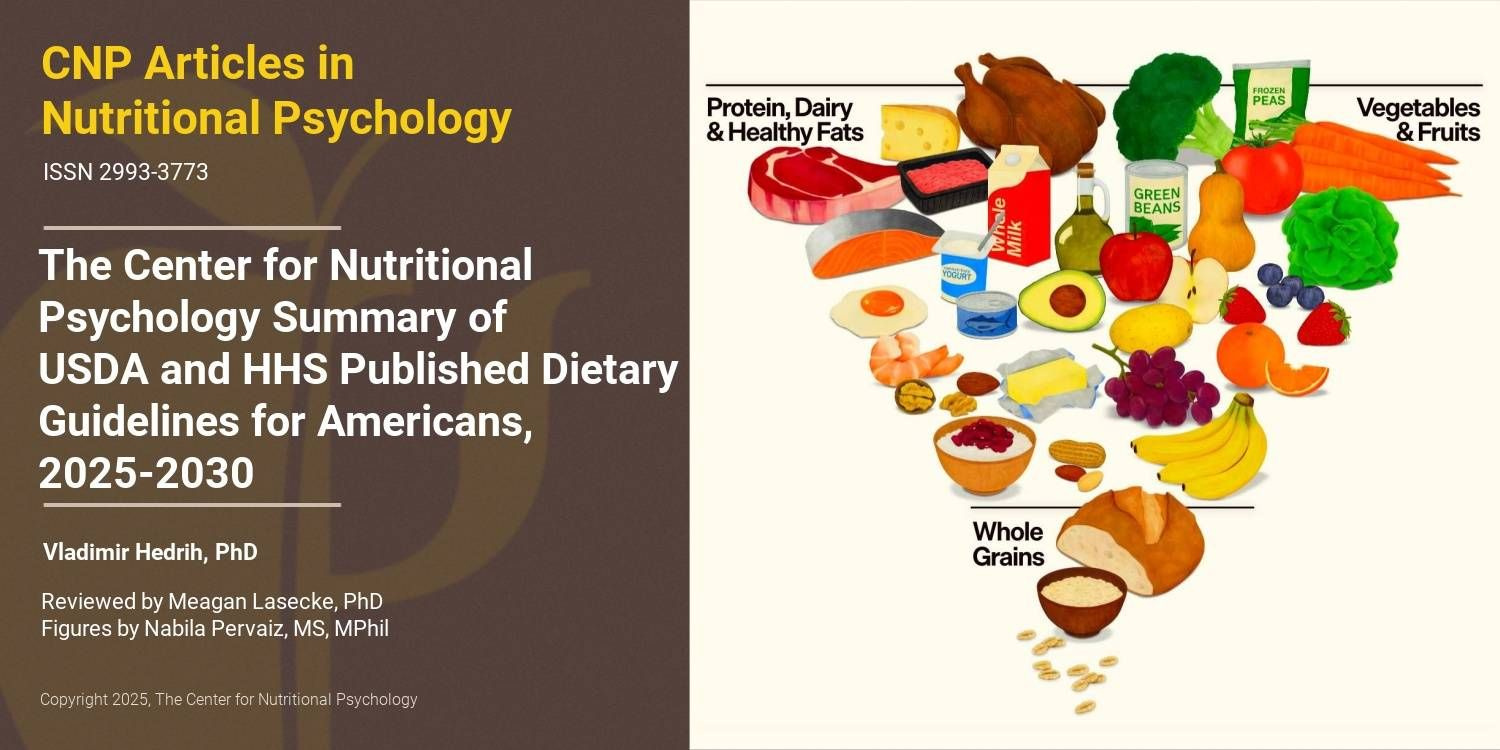

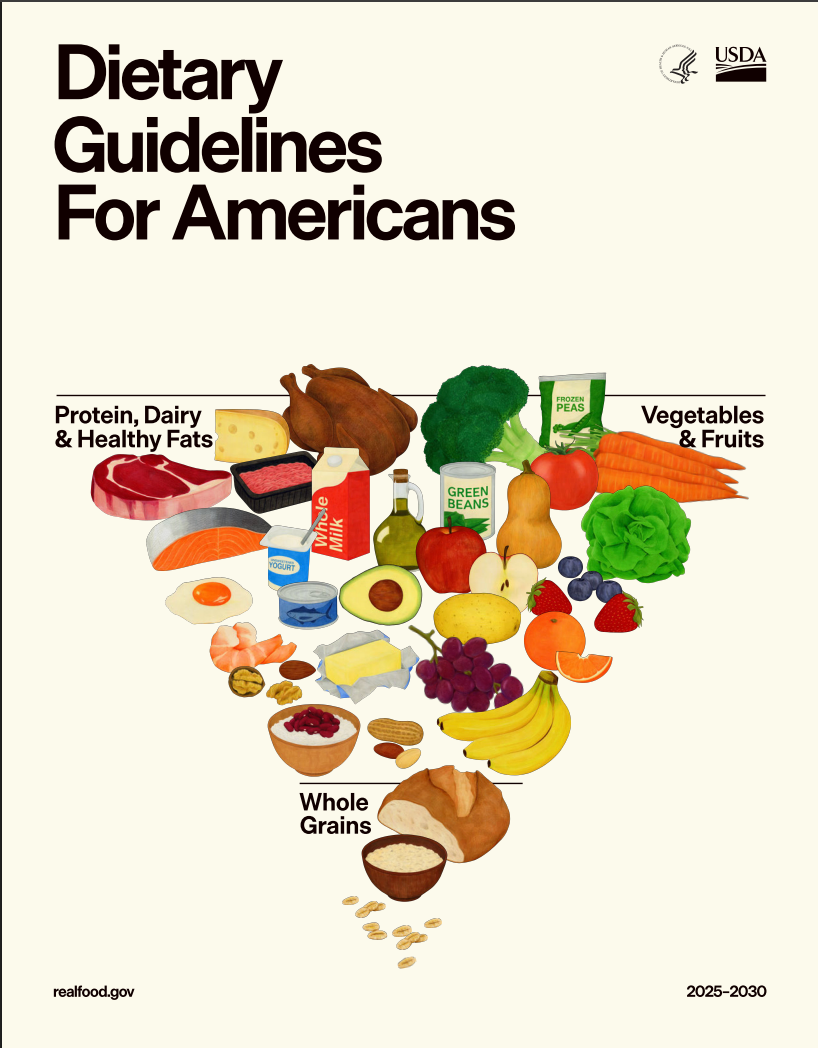

- The Guidelines state that American households must prioritize diets built on whole, nutrient-dense foods—protein, dairy, vegetables, fruits, healthy fats, and whole grains.

- Focusing on the well-established links between diets rich in highly processed food and chronic diseases, the Guidelines call for a dramatic reduction in “highly processed foods laden with refined carbohydrates, added sugars, excess sodium, unhealthy fats, and chemical additives”.

In recent decades, there have been significant shifts in global human health. On the one hand, life expectancy has been increasing. Life expectancy in the U.S. increased from 69.9 years in 1959 to 78.9 years in 2016 (Woolf & Schoomaker, 2019).

Shifts in Chronic Disease, Diabetes, Obesity, and Food Processing Trends

On the other hand, the prevalence of certain chronic diseases has increased substantially. For example, the prevalence of diabetes in the U.S. increased from 9.7% in 1999-2000 to 14.3% in August 2021-August 2023 (Woolf & Schoomaker, 2019). Worldwide, the number of people suffering from diabetes has almost quadrupled between 1990 and 2022 (Zhou et al., 2024). Also, statistics have recorded the onset of a global obesity epidemic in the previous decades (Wong et al., 2022). At the same time, the last century has seen a massive shift in diets towards highly processed and ultra-processed foods (Baker et al., 2020).

Nutrition and health

For much of human history, the link between nutrition and health was characterized by efforts to ensure adequate caloric intake and avoid malnutrition. A substantial (but decreasing) portion of humanity still faces food insecurity and even famines on a regular basis. However, for most of the world’s population, the relationship between nutrition and health has shifted toward mitigating the adverse health effects of industrially processed foods, excessive calorie intake, and insufficient intake of key micronutrients and fiber.

For example, studies have linked high intake of food containing refined, added sugar with a whole host of adverse health conditions, ranging from cardiovascular diseases to diabetes and obesity, to cancer (Huang et al., 2023). Similarly, the consumption of ultra-processed foods has been linked to increased risk of mortality, cancer, and various mental health, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic adverse health outcomes (Lane et al., 2024).

Ultra-processed foods are industrially processed foods made from refined ingredients and often contain additives and preservatives, with little to no whole-food content (Encyclopedia of Nutritional Psychology, 2025). Multiple studies have marked them as an important contributor to a condition called food addiction (Gearhardt et al., 2023). For example, a recent study in Turkey found that individuals consuming higher quantities of ultra-processed food tended to report slightly more severe symptoms of food addiction, but also more severe symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression (Hedrih, 2025; Mengi Çelik et al., 2025).

Nutrition and mental health

Studies are also increasingly reporting associations between nutrition and mental health. Globally, nearly 1 in 7 people, approximately 1.1 billion individuals, live with a mental disorder (World Health Organization [WHO], 2025). In fact, obesity, a chronic, relapsing disease affecting over 1 billion people worldwide, is a prevalent somatic comorbidity in individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD), significantly influencing the disorder’s trajectory and prognosis (Celletti et al., 2025; Opel et al., 2025).

Obesity is a prevalent somatic comorbidity in individuals with major depressive disorder.

The relatively recent discovery of the microbiota-gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication pathway linking the gut microbiome and the central nervous system through microbial metabolites, neurotransmitters and immune system interactions (Rathore et al., 2025), has produced studies demonstrating that changes in gut microbiome composition are associated with – and might even directly influence – mental health conditions such as Alzheimer’s dementia or social anxiety (Hedrih, 2024; Kim et al., 2021; Ritz et al., 2024). Additionally, disturbances in gut-brain signaling in depressed individuals have been found to alter food preferences. More specifically, a recent study found that depressed individuals exhibit lower wanting and liking for high-protein, high-fat foods when they are low in carbohydrates (but not when they are high in carbohydrates) (Hedrih, 2025a; Thurn et al., 2025).

On the other hand, some gut microorganisms have been associated with positive mental health outcomes such as stress resilience (e.g., Merchak et al., 2024) and depression and mood (Baião et al., 2023). It should be noted that gut microbiota composition largely depends on the diet a person consumes, particularly on substances that support microorganisms and on food components that gut microorganisms metabolize (Rinninella et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2017).

From a broader perspective, studies have, for example, found high levels of dietary sugar consumption to be associated with increased risk of depression (Zhang et al., 2024), while high levels of junk food consumption have been found to be associated with both higher stress levels and a higher risk of depression (Karim et al., 2025; Ejtahed et al., 2024).

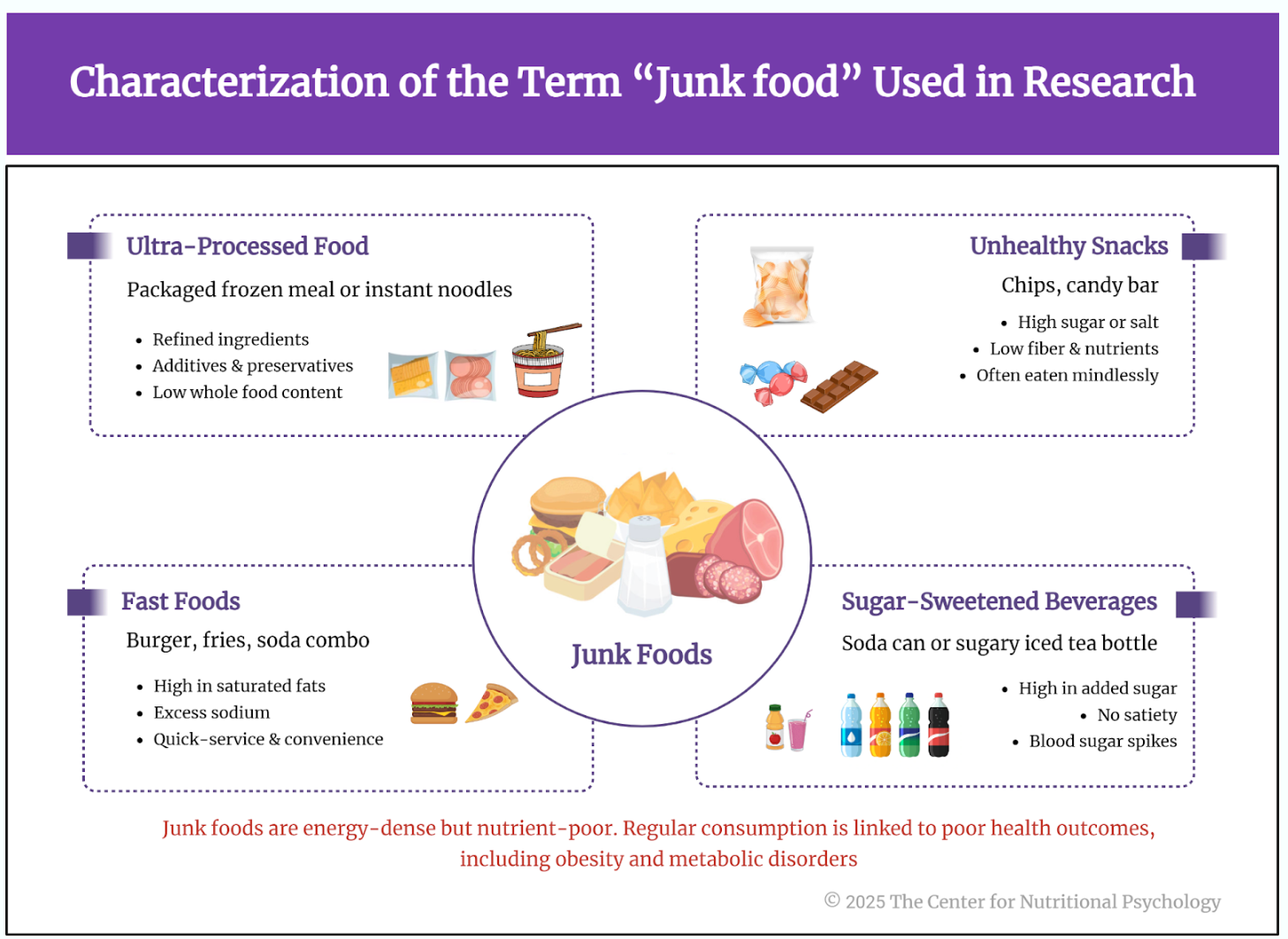

More specifically, a meta-analysis published in BMC Psychiatry found that individuals consuming junk food frequently had 30% higher odds of developing depression and 31% higher odds of experiencing heightened stress symptoms compared to people not consuming junk food or consuming it less often. Junk food consumption was also associated with 16% higher odds of developing mental health disorders and with 15% higher odds of experiencing heightened depression and stress symptoms. The meta-analysis included 17 studies that included a total of 159,885 participants (Ejtahed et al., 2024; Hedrih, 2025a). See Figure 1 to learn more about the term “junk food” used in research.

Figure 1. Characterization of the term “junk food” used within research

On the other hand, adherence to certain healthy diets, such as the EAT-Lancet diet, has been found to be associated with a lower risk of depression (Lu et al., 2024). Overall, hundreds of studies have reported associations between diet and mental health, and new studies are published daily (CNP Resource Library, 2026).

Overall, hundreds of studies have reported links between diet and mental health, and new ones are published every day.

It is important to note that obesity particularly frequently occurs in individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) and vice versa, significantly influencing the trajectory and prognosis of these disorders (Opel et al., 2025). This links the obesity epidemic to issues in mental health as well, further exacerbating the health consequences. Some researchers note strong parallels between compulsive overeating and substance use disorders, with overlapping symptoms and shared neurobiological pathways involving the mesolimbic dopamine system. Authors Gupta, Gupta & Khurana (2025) make the case for inclusion of obesity as a behavioral addiction in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. They further state that “although obesity lacks formal addiction criteria, viewing certain eating behaviors through an addiction framework may improve classification, treatment planning, and outcome prediction”.

Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Background and Policy Context)

Since 1980, the United States government has published the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Published every 5 years, these documents serve as a foundational cornerstone for federal nutrition policy. The guidelines incorporate current findings in nutritional science and translate them into practical guidance to enhance Americans’ overall health.

The Guidelines are published jointly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). While the first three editions were voluntary, since the 1995 edition, the guidelines have been prepared according to the 1990 National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act, which requires that the guidelines be reviewed by a committee of experts, updated if necessary, and published every 5 years (Watts et al., 2011).

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025–2030 (Publication, Rationale, and Key Stats)

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030, were published in January 2026. They start with an alarming note that 90% of health care spending goes to treating people who have chronic diseases, diseases that are a predictable result of the Standard American Diet, reliant on highly processed foods coupled with a sedentary lifestyle (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2026). They also note that 70% of American adults are overweight or obese, while 1 in 3 Americans between the ages of 12 and 17 has prediabetes.

70% of American adults are overweight or obese, while 1 in 3 Americans between the ages of 12 and 17 has prediabetes.

With a call to “Make America Healthy Again,” the guidelines advise Americans to return to the basics. Guidelines declare that “American households must prioritize diets built on whole, nutrient-dense foods—protein, dairy, vegetables, fruits, healthy fats, and whole grains.” When paired with a dramatic reduction in highly processed foods containing refined carbohydrates, added sugars, excess sodium, unhealthy fats, and chemical additives, this approach can change the health trajectory for many Americans.

Read the Guidelines.

The Main Points of the 2025–2030 Guidelines

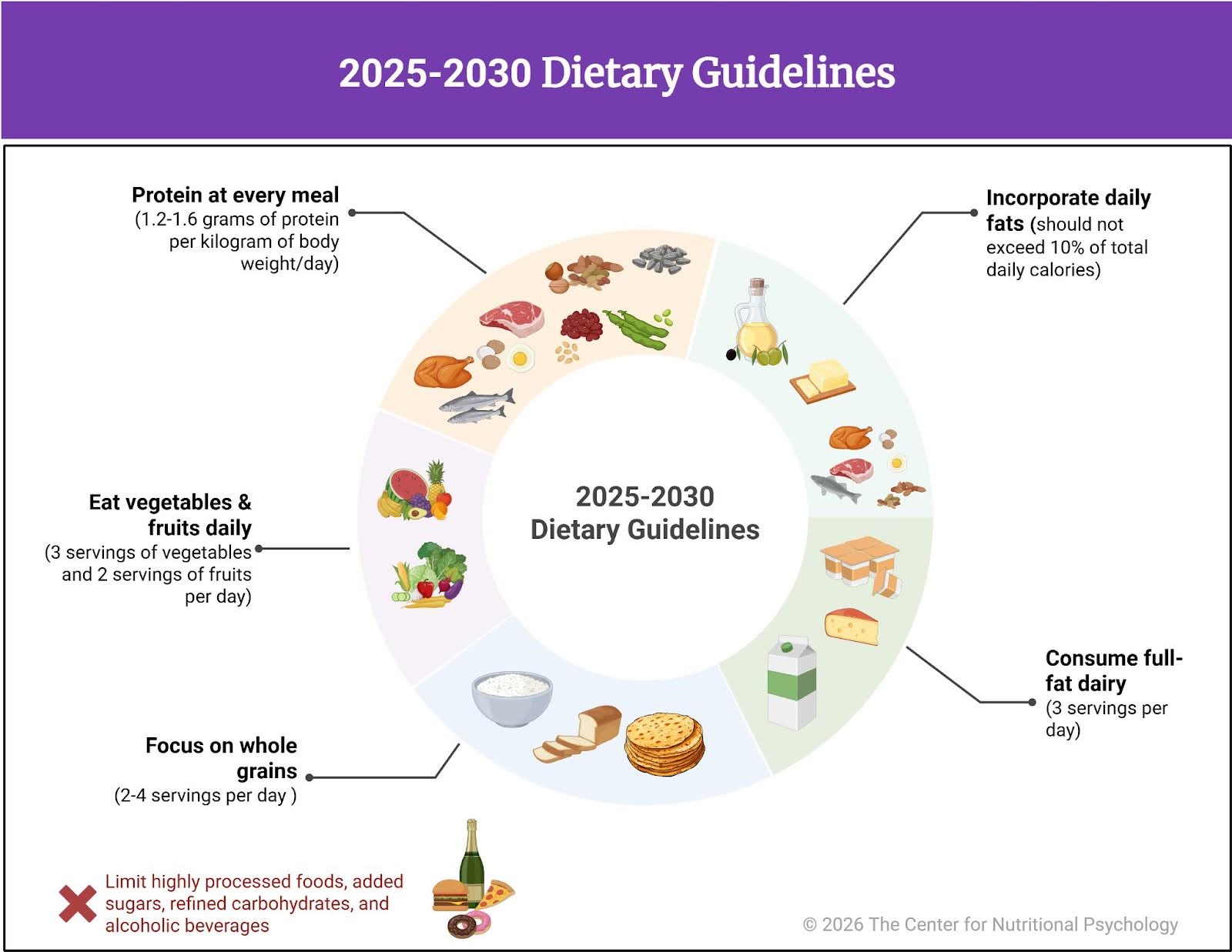

The main points in the 2025-2030 guidelines are (see Figure 2):

-

Portion size and beverages

Eat the right amount for you – portion sizes of food and beverage intake need to be adjusted to the individual. Optimal portion size depends on factors such as age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity. People are encouraged to choose water and unsweetened beverages.

-

Protein targets (1.2–1.6 g/kg/day) and sources

Prioritize protein at every meal – high-quality, nutrient-dense protein foods should be prioritized. The diet should include a variety of protein sources from animal and plant sources, including eggs, poultry, seafood, and red meat, as well as plant-based protein foods such as beans, peas, lentils, legumes, nuts, seeds, and soy. Deep-frying should be replaced with other methods, such as grilling, roasting, or baking. Meats should be without, or with limited, sugar and other additives, but flavors such as salt, spices, and herbs may be used. The guidelines suggest 1.2-1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, adjusting as needed for individual caloric requirements.

-

Dairy

Consume dairy – full-fat dairy with no added sugars. The guidelines recommend 3 servings per day, adjusted as needed for individual caloric requirements.

-

Fruits and vegetables

Eat fruits and vegetables throughout the day – the guidelines recommend fresh or canned fruits and vegetables, with no or very limited added sugars. 3 servings of vegetables and 2 servings of fruits per day are suggested.

-

Healthy fats

Incorporate healthy fats – cooking should prioritize oils with essential fatty acids, such as olive oil, butter, and beef tallow, which are also an option. The guidelines list specific foods rich in healthy fats, such as meats, poultry, eggs, seafood, nuts, or seeds, but note that these fats should not exceed 10% of total daily calories.

-

Whole grains

Focus on whole grains – fiber-rich whole grains should be prioritized, with 2-4 servings per day being the recommended amount. On the other hand, people should reduce their consumption of highly processed and refined carbohydrates, such as white bread, flour tortillas, crackers, and packaged breakfast options.

-

Limits: highly processed foods, added sugars, refined carbs, alcohol

Limit highly processed foods, added sugars, refined carbohydrates, and alcoholic beverages – studies firmly link all these food/beverage categories with increased risk of various chronic diseases and adverse health outcomes.

-

Guidance for specific populations

Aside from these general recommendations, the 2025-2030 guidelines give specific provisions for infants and children of different ages, young adults, pregnant and lactating women, older adults, individuals with chronic diseases, vegetarians, and vegans.

Figure 2. 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines summary

Changes From the 2020–2025 Guidelines

Compared with the 2020-2025 guidelines, the 2025-2030 guidelines place greater emphasis on food quality and the extent of processing than on individual nutrients. They advise that the diet should be centered on whole and minimally processed foods, and that added sugars/refined carbohydrates, and highly processed foods should be very limited. However, this does not imply neglecting the taste of food; it can be achieved through the use of spices.

These guidelines also place greater, more direct emphasis on the links between dietary patterns and metabolic health, rather than treating foods solely as sources of individual nutrients. From the outset, the 2025-2030 guidelines regard a healthy diet as a means of preventing chronic diseases and improving long-term health outcomes.

Conclusion and Implications for Nutritional Psychology

Overall, the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans shift the focus from isolated nutrients to food quality, processing, and overall dietary patterns. They emphasize that dietary patterns should be tailored to the individual’s specific needs. This is close to how people actually perceive and choose foods – as specific food items with their own qualities, rather than as collections of individual nutrients.

The guidelines also address the roles of food environments and food preparation and consumption habits — topics central to nutritional psychology. The recognition of the links between dietary patterns (as a whole) and metabolic health makes psychological models describing food-related behavior, self-regulation, and well-being particularly relevant. Finally, noting that an optimal diet should be both healthy and palatable, guidelines implicitly recognize the relevance of psychological experiences, such as enjoyment of food, and their importance for overall well-being.

The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans were jointly prepared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and published at https://realfood.gov/.

References

Baião, R., Capitão, L. P., Higgins, C., Browning, M., Harmer, C. J., & Burnet, P. W. J. (2023). Multispecies probiotic administration reduces emotional salience and improves mood in subjects with moderate depression: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychological Medicine, 53(8), 3437–3447. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172100550X

Baker, P., Machado, P., Santos, T., Sievert, K., Backholer, K., Hadjikakou, M., Russell, C., Huse, O., Bell, C., Scrinis, G., Worsley, A., Friel, S., & Lawrence, M. (2020). Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obesity Reviews, 21(12), e13126. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13126

Celletti, F., Farrar, J., & De Regil, L. (2025). World Health Organization guideline on the use and indications of glucagon-like peptide-1 therapies for the treatment of obesity in adults. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.24288

CNP Resource Library. (2026). The Center for Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/np-research-library/

Ejtahed, H.-S., Mardi, P., Hejrani, B., Mahdavi, F. S., Ghoreshi, B., Gohari, K., Heidari-Beni, M., & Qorbani, M. (2024). Association between junk food consumption and mental health problems in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 438. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05889-8

Encyclopedia of Nutritional Psychology. (2025). The Center for Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/encyclopedia/

Gearhardt, A. N., Bueno, N. B., DiFeliceantonio, A. G., Roberto, C. A., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2023). Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction. BMJ, e075354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354

Hedrih, V. (2024, January 29). Can Symptoms of Alzheimer’s be Transferred to Rats via the Gut Microbiota of Alzheimer’s Patients? CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/can-symptoms-of-alzheimers-be-transferred-to-rats-via-the-gut-microbiota-of-alzheimers-patients/

Huang, Y., Chen, Z., Chen, B., Li, J., Yuan, X., Li, J., Wang, W., Dai, T., Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wang, P., Guo, J., Dong, Q., Liu, C., Wei, Q., Cao, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 381, e071609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071609

Karim, S., Alam, A. S., & Syed, A. (2025). Association between ultra-processed food consumption and risk of developing depression in adults: A systematic review. EMJ Gastroenterology, 14(1), 64-74. https://doi.org/10.33590/emjgastroenterol/IVVG9805

Kim, N., Jeon, S. H., Ju, I. G., Gee, M. S., Do, J., Oh, M. S., & Lee, J. K. (2021). Transplantation of gut microbiota derived from Alzheimer’s disease mouse model impairs memory function and neurogenesis in C57BL/6 mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 98, 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBI.2021.09.002

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., Ashtree, D. N., McGuinness, A. J., Gauci, S., Baker, P., Lawrence, M., Rebholz, C. M., Srour, B., Touvier, M., Jacka, F. N., O’Neil, A., Segasby, T., & Marx, W. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

Lu, X., Wu, L., Shao, L., Fan, Y., Pei, Y., Lu, X., Borné, Y., & Ke, C. (2024). Adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet and incident depression and anxiety. Nature Communications, 15(1), 5599. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49653-8

Merchak, A. R., Wachamo, S., Brown, L. C., Thakur, A., Moreau, B., Brown, R. M., Rivet-Noor, C. R., Raghavan, T., & Gaultier, A. (2024). Lactobacillus from the Altered Schaedler Flora maintain IFNγ homeostasis to promote behavioral stress resilience. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 115, 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.11.001

Opel, N., Hanssen, R., Steinmann, L. A., Foerster, J., Köhler-Forsberg, O., Hahn, M., Ferretti, F., Palmer, C., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Gold, S. M., Reif, A., Otte, C., & Edwin Thanarajah, S. (2025). Clinical management of major depressive disorder with comorbid obesity. The Lancet Psychiatry. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(25)00193-2

Rathore, K., Shukla, N., Naik, S., Sambhav, K., Dange, K., Bhuyan, D., & Imranul Haq, Q. M. (2025). The bidirectional relationship between the gut microbiome and mental health: A comprehensive review. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.80810

Rinninella, E., Tohumcu, E., Raoul, P., Fiorani, M., Cintoni, M., Mele, M. C., Cammarota, G., Gasbarrini, A., & Ianiro, G. (2023). The role of diet in shaping human gut microbiota. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 62–63, 101828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2023.101828

Ritz, N. L., Brocka, M., Butler, M. I., Cowan, C. S. M., Barrera-Bugueño, C., Turkington, C. J. R., Draper, L. A., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Turpin, V., Morales, L., Campos, D., Gheorghe, C. E., Ratsika, A., Sharma, V., Golubeva, A. V., Aburto, M. R., Shkoporov, A. N., Moloney, G. M., Hill, C., … Cryan, J. F. (2024). Social anxiety disorder-associated gut microbiota increases social fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(1), e2308706120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308706120

Singh, R. K., Chang, H., Yan, D., Lee, K. M., Ucmak, D., Wong, K., Abrouk, M., Farahnik, B., Nakamura, M., Zhu, T. H., Bhutani, T., & Liao, W. (2017). Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. Journal of Translational Medicine, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y

U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2026). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030. https://realfood.gov

Watts, M. L., Hager, M. H., Toner, C. D., & Weber, J. A. (2011). The art of translating nutritional science into dietary guidance: History and evolution of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Nutrition Reviews©, Vol. 69, No. 7. Nutrition Reviews, 69(7), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00408.x

Wong, M. C., Mccarthy, C., Fearnbach, N., Yang, S., Shepherd, J., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2022). Emergence of the obesity epidemic: 6-decade visualization with humanoid avatars. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(4), 1189–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC005

Woolf, S., & Schoomaker, H. (2019). Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA, 322(20), 1996–2016. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.16932

World Health Organization. (2025, September 2). Over a billion people living with mental health conditions – services require urgent scale-up. Who.int; World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-09-2025-over-a-billion-people-living-with-mental-health-conditions-services-require-urgent-scale-up

Zhang, L., Sun, H., Liu, Z., Yang, J., & Liu, Y. (2024). Association between dietary sugar intake and depression in US adults: A cross-sectional study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2018. BMC Psychiatry, 24(110), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05531-7

Zhou, B., Rayner, A. W., Gregg, E. W., Sheffer, K. E., Carrillo-Larco, R. M., Bennett, J. E., Shaw, J. E., Paciorek, C. J., Singleton, R. K., Barradas Pires, A., Stevens, G. A., Danaei, G., Lhoste, V. P., Phelps, N. H., Heap, R. A., Jain, L., D’Ailhaud De Brisis, Y., Galeazzi, A., Kengne, A. P., … Ezzati, M. (2024). Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. The Lancet, 404(10467), 2077–2093. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02317-1

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), and who publishes them?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans are the U.S. government’s official nutrition guidelines, published every 5 years. They are published jointly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and translate current nutrition science into practical guidance to improve health.

When were the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025–2030 published?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025–2030 were published in January 2026.

What do the 2025–2030 guidelines emphasize most?

The guidelines state that American households must prioritize diets built on whole, nutrient-dense foods—protein, dairy, vegetables, fruits, healthy fats, and whole grains. They also call for a dramatic reduction in highly processed foods containing refined carbohydrates, added sugars, excess sodium, unhealthy fats, and chemical additives.

What are the main recommendations in the 2025–2030 guidelines?

The guidelines emphasize adjusting portion sizes to the individual and choosing water or unsweetened beverages. They also prioritize high-quality protein at every meal (including a suggested range of 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day), consuming full-fat dairy with no added sugars, eating fruits and vegetables throughout the day, incorporating healthy fats (not exceeding 10% of total daily calories), focusing on fiber-rich whole grains, and limiting highly processed foods, added sugars, refined carbohydrates, and alcoholic beverages.

How do the 2025–2030 guidelines differ from the 2020–2025 guidelines?

Compared with the 2020–2025 guidelines, the 2025–2030 guidelines place greater emphasis on food quality and the extent of processing than on individual nutrients. They more directly emphasize links between dietary patterns and metabolic health and frame a healthy diet as a means of preventing chronic disease and improving long-term health outcomes.

Why are the 2025–2030 guidelines relevant to nutritional psychology?

The guidelines address food environments and food preparation and consumption habits, which are central to nutritional psychology. By emphasizing dietary patterns, palatability, and long-term metabolic health, they align with psychological models describing food-related behavior, self-regulation, and well-being.

Navigation

Navigation