How Expectations Change Our Body’s Response to Food, Study Finds

Listen to this Article

- A study published in Health Psychology found that one’s expectations affect physiological responses to food

- Participants who believed that the milkshake they consumed was high-calorie showed a much steeper decline in ghrelin level compared to participants who believed that the same shake was low-calorie.

- Participants’ feelings of satiety were consistent with what they believed they were consuming rather than with what they actually consumed

We have all experienced situations when our expectation and body response shaped our reactions and perceptions of events more than the actual developments. Attending a party and expecting to have a good time can significantly contribute to the overall experience of that party. Similarly, coming to an exam with the expectation that we will do well will easily motivate us to put in more effort in our work and actually perform better than if we came expecting to fail.

Expectations are important!

Scientists have long recognized that expectations play a crucial role in determining behavior. In his classic experiment from the 1950s, Curt Richter observed that rats initially placed in a water container where they must keep swimming to survive, as they cannot escape, tend to drown quickly. This was particularly true of wild rats. However, if rescued once, they would swim for much longer periods upon subsequent immersions (expecting that they will be rescued) (Richter, 1957). Although this experiment lacked the stringency of modern scientific experiments, it yielded a powerful finding that demonstrated the significant role of expectations in shaping behavior.

Since that time, numerous scientific findings have confirmed that expectations can significantly influence human perceptions. This includes the area of nutrition and food behavior. For example, a 2022 study found that people perceive food as tastier when it is eaten in an aesthetically pleasing environment (Hedrih, 2023; Wu et al., 2022). Another study showed that increasing the price of a wine makes people report its flavor as more pleasant, while also increasing activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex of the brain (an area thought to be responsible for experienced pleasantness) during wine consumption (Plassmann et al., 2008). On the opposite pole of expectations, a study found that people tend to give lower liking ratings to foods if they were labeled as low-fat (Wardle & Solomons, 1994).

Expectations and physiological changes

The effects of expectations seem to go beyond psychological experiences. They can affect physiological parameters of the body as well. Studies have shown that people learn to expect meals at a certain time of day, and their bodies adjust blood sugar levels accordingly (Isherwood et al., 2023).

Similarly, numerous studies demonstrate that the body responds with fluctuating hormone levels, including insulin, ghrelin, pancreatic polypeptide, and glucagon, when a person sees or smells food, thereby initiating meal anticipation (Skvortsova et al., 2021).

The current study

Study author Alia J. Crum and her colleagues sought to determine whether subtle changes in mindset regarding the characteristics of what people eat might influence the release of ghrelin in response to food consumption (Crum et al., 2011). Ghrelin is a hormone primarily produced in the stomach that stimulates hunger by signaling the brain to increase appetite. Its levels rise before meals and fall sharply after eating begins.

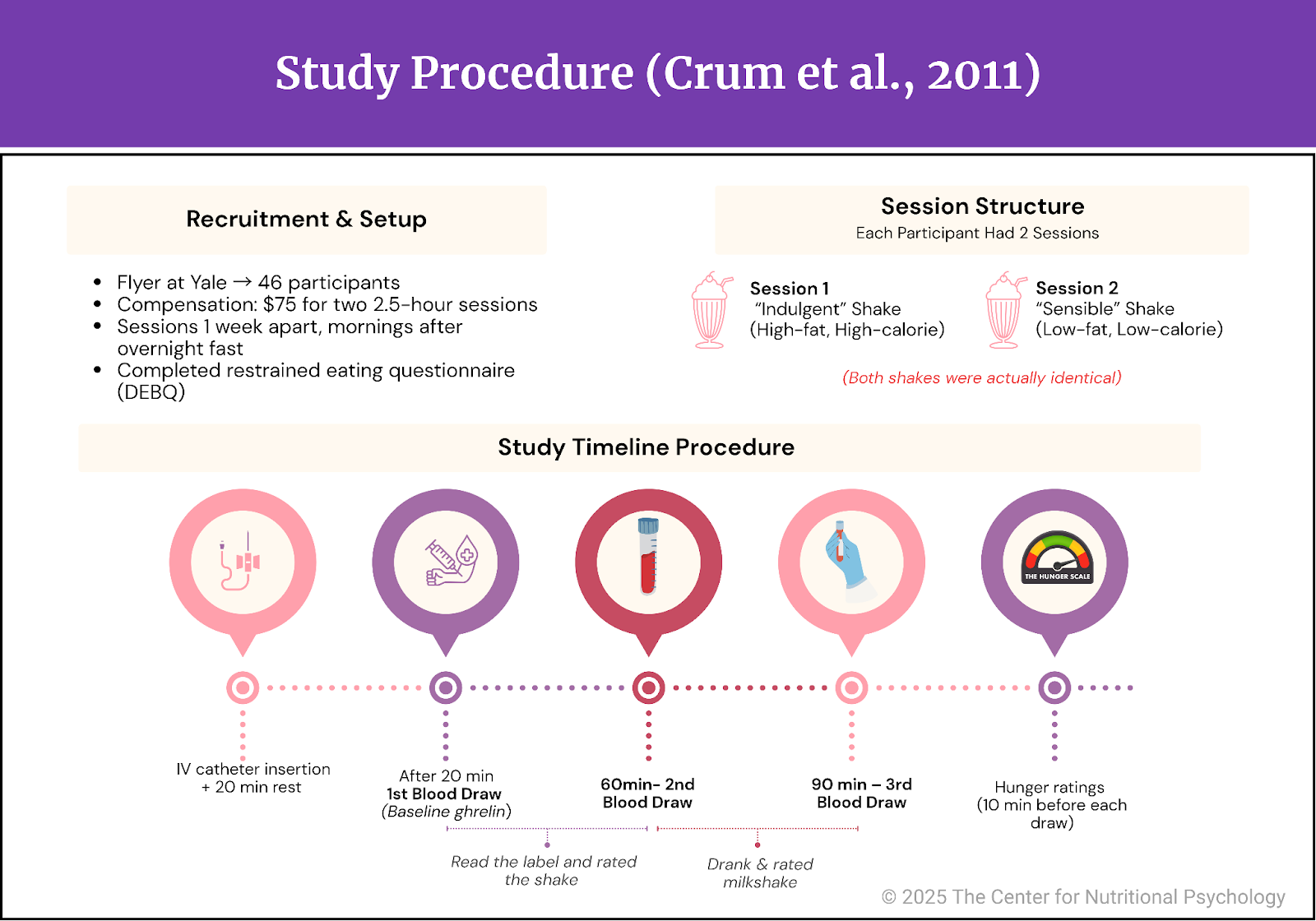

Study participants were recruited through fliers presenting an opportunity to participate in a “Shake Tasting Study” at the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation in exchange for $75 for two 2.5-hour sessions. In this way, the study authors recruited 46 participants who completed all components of the study. These sessions were exactly one week apart and took place in the morning after an overnight fast.

The study authors informed participants that their institution’s kitchen was preparing two different milkshakes for them to test. In one session, participants were to test one of the milkshakes, while they would taste the other in the second session. In reality, both milkshakes were identical. However, the label on the milkshake in one session said that it is a high-fat, high-calorie “indulgent” milkshake (aiming to induce an indulgent mindset about it). In contrast, in the other session, the label read that it is a low-fat, low-calorie “sensible” milkshake.

At the start of each session, participants had an intravenous catheter inserted for blood drawing. After a 20-minute rest, the study authors drew the first blood sample. New blood samples were taken at 60 and 90 minutes after the start of the procedure. Study authors used these blood samples to determine ghrelin levels.

During the first interval, participants were asked to view and rate the label of the shake. During the interval between the second and the third blood drawing, participants were asked to drink and rate the milkshake. Participants rated the taste, smell, appearance, enjoyment, and overall healthiness of the milkshake on a visual analogue scale. They rated their own hunger levels 10 minutes prior to each blood drawing. Participants also completed an assessment of restrained eating (the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Procedure (Crum et al., 2011)

Ghrelin levels drop sharply when participants believe they drank a high-calorie milkshake

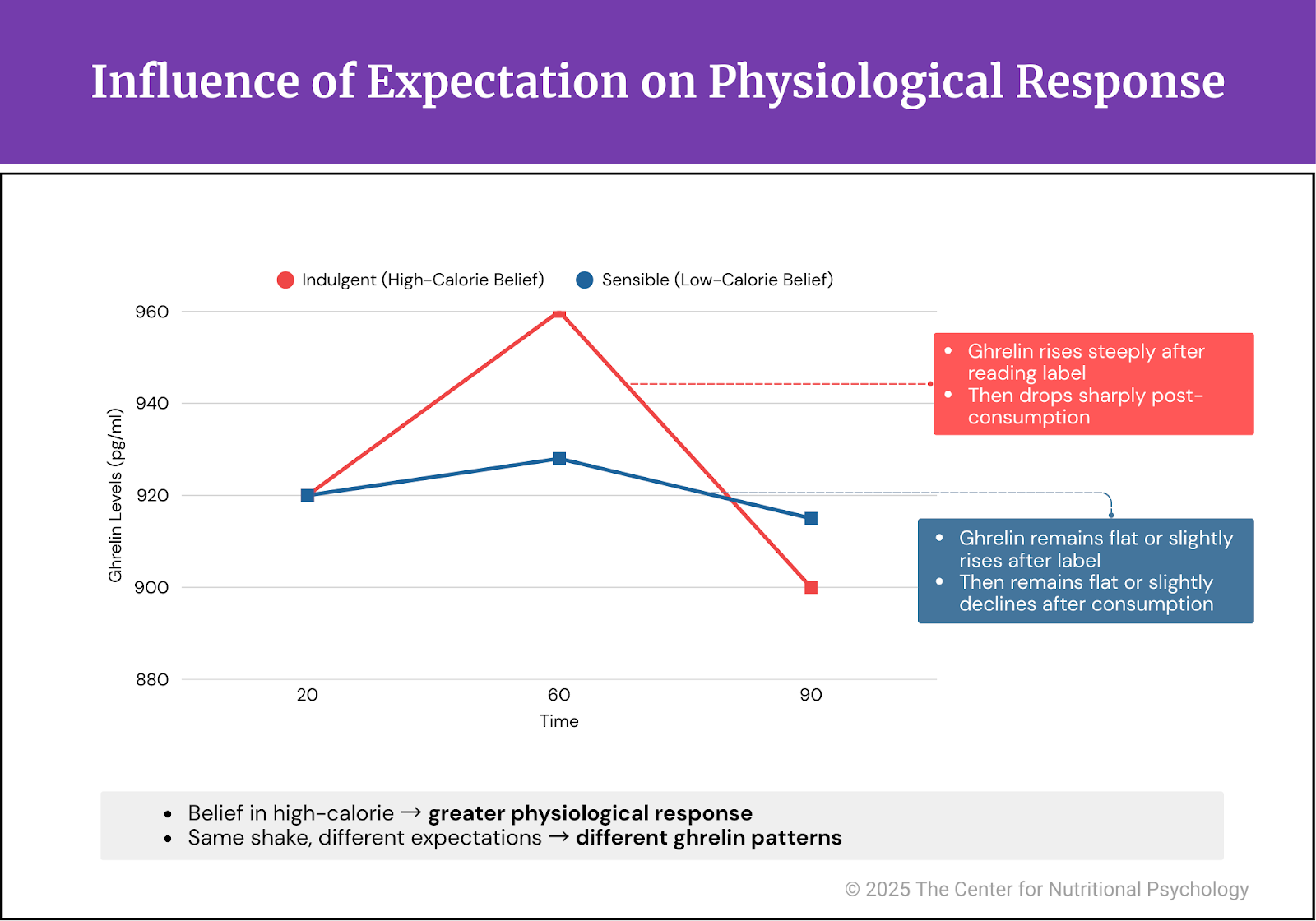

Results showed that participants rated the milkshake they believed to be low-calorie as much healthier than the same milkshake when they believed it was high-calorie. After reading the milkshake label, participants exhibited a steeper rise in ghrelin levels when the label indicated that the milkshake was a high-calorie shake than when it stated that it was low-calorie. After consuming the milkshake, the reduction in ghrelin levels was much steeper when participants believed that the milkshake was high-calorie.

In contrast, anticipation of a low-calorie milkshake resulted in either flat or only slightly increased ghrelin levels. After drinking it, ghrelin levels either remained similar or declined slightly, suggesting that participants were not physiologically satisfied, despite consuming the same nutrient contents. Participants’ satiety was consistent with what they believed they were consuming, rather than with the actual nutritional value of what they consumed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Influence of expectation on physiological response.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that expectations and the mindset with which one approaches food can influence the physiological responses to consuming it. In this case, ghrelin levels in participants’ blood were more affected by their expectations than by the nutrient content of the milkshake they consumed.

This suggests that policies aimed at promoting healthy dietary habits and meal plans in general should consider people’s expectations about food and the mindset with which they approach it, rather than focusing solely on the nutritional content of food. The same goes for research studies examining the physiological and psychological effects of consuming specific foods.

The paper “Mind Over Milkshakes: Mindsets, Not Just Nutrients, Determine Ghrelin Response” was authored by Alia J. Crum, William R. Corbin, Kelly D. Brownell, and Peter Salovey.

References

Crum, A. J., Corbin, W. R., Brownell, K. D., & Salovey, P. (2011). Mind over milkshakes: Mindsets, not just nutrients, determine ghrelin response. Health Psychology, 30(4), 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023467

Hedrih, V. (2023, June 12). Is Food Tastier When Consumed in Aesthetically Pleasing Environments? CNP Articles in Nutritional Psychology. https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/is-food-tastier-when-consumed-in-aesthetically-pleasing-environments/

Isherwood, C. M., van der Veen, D. R., Hassanin, H., Skene, D. J., & Johnston, J. D. (2023). Human glucose rhythms and subjective hunger anticipate meal timing. Current Biology, 33(7), 1321-1326.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.005

Plassmann, H., O’Doherty, J., Shiv, B., & Rangel, A. (2008). Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(3), 1050–1054. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706929105

Richter, C. P. (1957). On the Phenomenon of Sudden Death in Animals and Man. Psychosomatic Medicine, 19(3).

Skvortsova, A., Veldhuijzen, D. S., Kloosterman, I. E. M., Pacheco-López, G., & Evers, A. W. M. (2021). Food anticipatory hormonal responses: A systematic review of animal and human studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 126, 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.030

Wardle, J., & Solomons, W. (1994). Naughty but nice: A laboratory study of health information and food preferences in a community sample. Health Psychology, 13(2), 180–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.13.2.180

Wu, C., Zhu, H., Huang, C., Liang, X., Zhao, K., Zhang, S., He, M., Zhang, W., & He, X. (2022). Does a beautiful environment make food better—The effect of environmental aesthetics on food perception and eating intention. Appetite, 175(April), 106076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106076

Navigation

Navigation

Leave a comment